Walking Tour

Princeton's Settler Story

Episodes in Princeton History

Andrew Farris, Alexa Dagan

For a town of its size, Princeton has a rich, fascinating, and surprisingly turbulent history. The region's mineral wealth, from ochre to copper, coal and even gold, has played an important role in making Princeton's history so interesting. The ebb and flow of mining has led to frantic gold rushes, shocking economic collapses, overnight rags-to-riches stories, and bitterly fought labour struggles.

Princeton's history has also been marked by its geographical isolation, since the town is flanked on both sides by mountain ranges. The sagas of the Dewdney Trail, Kettle Valley Railway, and Hope-Princeton Highways furnish enough tales to fill volumes. This geographic isolation has left a lasting legacy on Princeton and led to the intense importance of horses to the local culture.

The scope of Princeton's history is too vast to comprehensively cover in a single tour. In this tour, we will look at some of the most exciting episodes from that history: stories like the ancient Vermilion Cave, the groundbreaking pioneer John Fall Allison and his wives, the 'Gentleman Bandit' Bill Miner, the gold rush at Granite Creek, and many more.

The tour route is fairly short. It begins on Vermilion Avenue and turns up onto Bridge Street, exploring the area where many of the town's most prominent buildings once stood.

This project is a partnership with the Town of Princeton and the Princeton & District Museum and Archives.

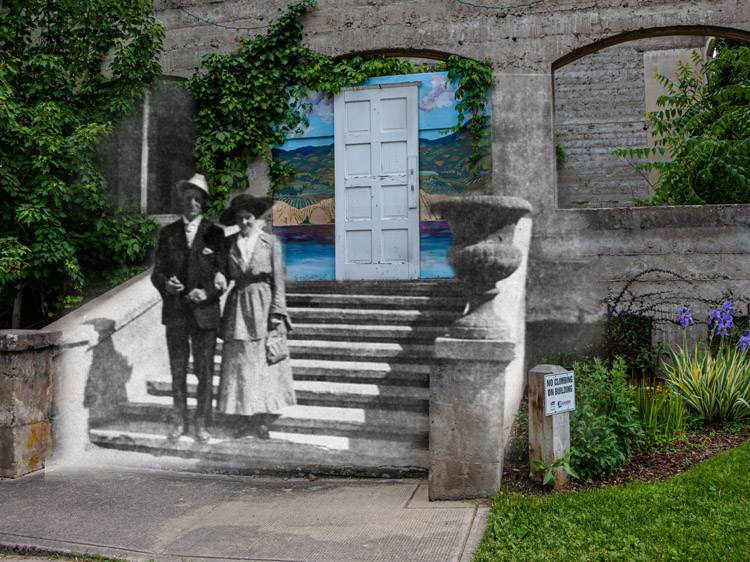

1. Starting at the Beginning

Princeton & District Museum Archives

1925

We start our tour of Princeton's history at the former site of the Princeton Brewing Company, which was renowned for its Old Gold Lager. The brewery opened at the beginning of the last century and operated under various names until 1961, when the company went under and the brewery was subsequently demolished. As you can see, the concrete foundations built into the sandstone wall remain.

* * *

Later, the cave was used by the brewery as a storage space for aging beer, and was apparently massive enough to hold 24 freight carloads of lager. Some even believed that aging the Princeton beer in the "Old Cave" was what gave it such a fine flavour.

The creation of the cave was thanks to the geological foundations underlying the town of Princeton. The town sits on sedimentary rock from the Eocene epoch, which lasted from 56 to 33.9 million years ago. The caves themselves were made of sandstone, a sedimentary rock consisting of minerals the size of grains of sand. Sandstone often forms cliffs and bluffs that stand out from the surrounding landscape. Sandstone caves such as the Vermillion Cave are formed by long-term erosion from wind or water that carves out cavities in the stone. Sandstone caves are often shallow; according to historical accounts, the Vermillion Cave was exceptionally large.

Sadly, in 1948, the cave was demolished to make way for the Hope-Princeton Highway. A geological and historical treasure was lost in the name of progress.

As we go through the tour, we will learn about much that has been lost, and also much that has been preserved. We will consider what parts of our shared heritage we should preserve for our children.

2. Vermilion Forks

Princeton & District Museum Archives

1950

Here we see a group of young men posing with the old sign that welcomed visitors to Princeton, which was once located a bit further up the road. They look like they are celebrating an occasion, perhaps graduation, and they are clearly proud of the town they call home.

* * *

The local Upper Similkameen people, or Upper Smelqmix, traded the ochre with other bands from across North America and left stunning pictographs all over the region. First Nations peoples from regions as far away as the prairies, modern-day Washington, and modern-day Oregon brought goods to the Similkameen to trade for the sacred ochre. First Nations' oral history says the Similkameen area has been home to the Upper Similkameen people since the beginning of time. This aligns with archaeological finds in the region that date as far back as 7,500 years ago.

The name Similkameen is thought to derive from Similkameigh, which comes from the now-extinct language of Nicola-Similkameen, an Athabascan language.1

In a tragedy repeated everywhere across the Americas, European-introduced diseases swept across the continent ahead of the colonists, killing millions and depopulating whole regions. In this region, it was no different. By the time the first Europeans arrived here, the diseases that preceded them had already decimated the Upper Similkameen.

Those first European fur traders and pioneers admired the red ochre found in the river here, and so gave the settlement its first English name: Vermilion Forks. It wasn't long before they discovered that a different set of valuable minerals were abundant here as well: copper, coal, and gold.

3. John Fall Allison

Okanagan Archive Trust Society

1911

A horse-drawn sleigh is parked outside the Similkameen Hotel, which was located on roughly this spot in the early 20th Century. In those early years, hotels like this were a welcome sight for exhausted travellers who made the gruelling trek to Princeton along the Dewdney Trail, which had been painstakingly cut from the mountain slopes by a company of Royal Engineers.

* * *

The first of these women was a 15-year-old member of the Upper Similkameen Band, Nora Yakumtikum, whose knowledge of the land and connections with the Indigenous peoples of the Okanagan played no small role in John's early survival and ability to prosper. She has been largely left out of local histories until recently.1

John's second wife was Susan Louisa Moir, who braved the tough pioneer life with John, bore him 14 children, and developed close relations with all of the nearby Indigenous bands. She later wrote and published widely praised ethnographic studies of the Lower and Upper Similkameen—a remarkable achievement for a woman in that era.

4. The Gentleman Bandit

Princeton & District Museum Archives

1920

On the left is the Similkameen Hotel, which we saw in the last photo. On the right is the old courthouse, which was responsible for dispensing justice in the Similkameen District. There was one local "loveable rogue" that many of the people of Princeton would have preferred to see escape justice. If you've ever said the phrase "Hands up!", you'll owe him a debt; he was the one who coined that saying.1

He was Bill Miner, Canada's last great train robber.

* * *

In 1904, Bill Miner enlisted the aid of Thomas “Shorty” Dunn, an American gunman, and held up the CPR’s Transcontinental Express No. 1 a few kilometres west of Mission. The operation went smoothly, and Bill Miner and his gang escaped with $6,000 worth of gold dust, more than $900 in currency, and $50,000 in US bonds. All the while, he maintained his cover as George Edwards.

Bill Miner robbed trains using the tried-and-true methods of the famous train robbers who came before him. First, the robbers would find a train at a location where it had stopped, or where a steep uphill climb forced it to slow significantly. The robbers would leap aboard the locomotive and take the engineer hostage.

The so-called express car, which was conveniently located directly behind the locomotive, contained shipments of valuables such as gold, currency, and mail. The robbers would unhook all the train cars behind the express car, leaving the hapless passengers stranded, and then force the engineer to drive them some ways ahead. This would give them free reign to plunder the express car. Sometimes, if a crewman refused to cooperate, they'd blast the express car's heavily secured doors open with dynamite.

During one of Edwards's frequent mysterious absences in May of 1906, a botched robbery of the CPR’s Transcontinental Express No. 97 led to the largest manhunt in BC history. The authorities were convinced that the culprits were the very same people who had committed the lucrative robbery back in 1904. They offered a staggering $15,000 reward for their capture. When Bill Miner was caught six days later, the people of Princeton were shocked to discover that their beloved George Edwards was actually the Gentleman Bandit, the Grey Fox, Bill Miner himself. The outlaw had earned the name the Gentleman Bandit for his polite demeanor during the height of a robbery.

Miner's story didn't end with his capture, however. He escaped from the British Columbia Penitentiary on August 8, 1907. Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier was furious about Miner's escape stating, “a dangerous criminal… thinking to play with impunity in this country the pranks he had been playing on the other side of the line… had been allowed to escape from the penitentiary.” But many in British Columbia sympathised with Miner, as a Robin-Hood-style legend had grown up around him. A popular anecdote circulated at the time about a man who allegedly said, “Oh, Bill Miner’s not so bad. He only robs the CPR once every two years. The CPR robs us all every day.”1

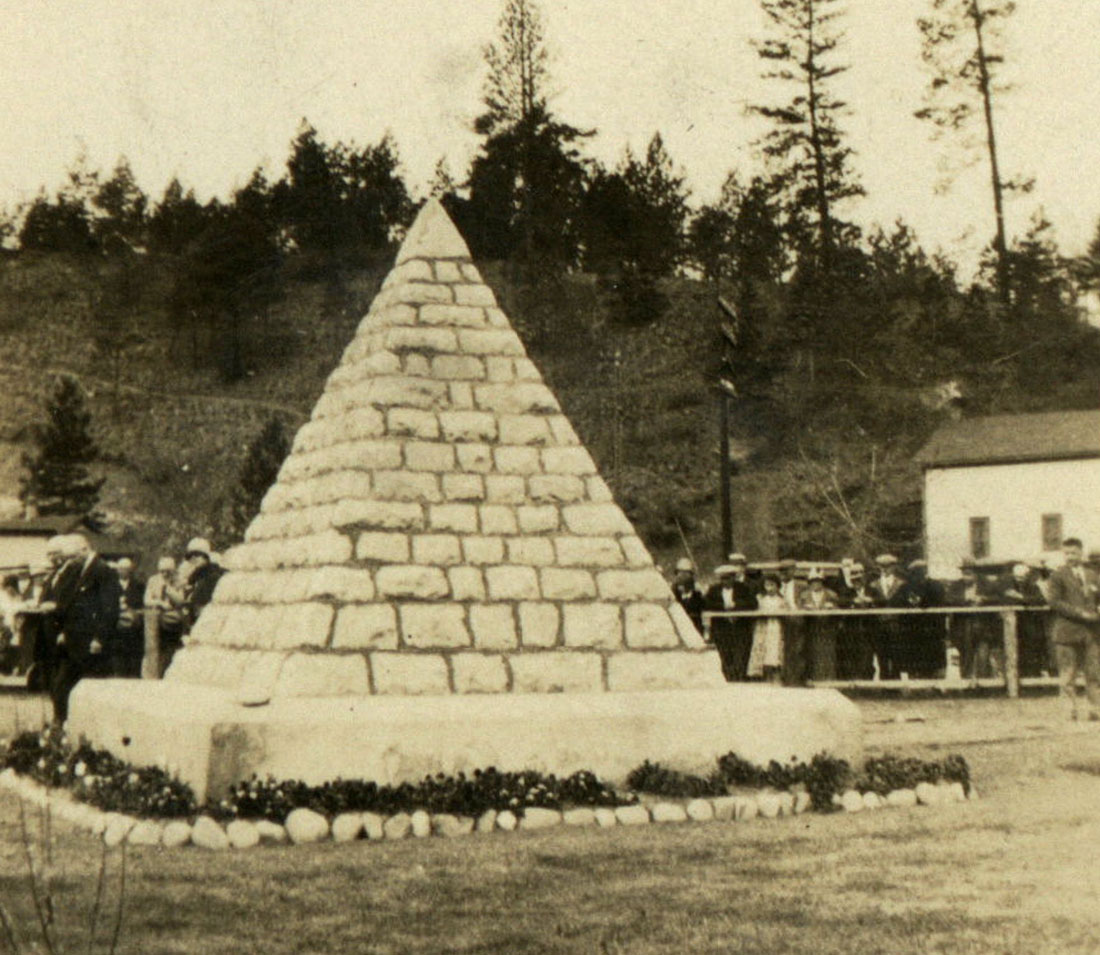

5. Princeton at War

Princeton & District Museum Archives

1929

This photo was taken at the unveiling of Princeton's cenotaph by Lieutenant Governor Robert Bruce. It was a solemn occasion, for Princeton had paid a steep price in the First World War, and her citizens would soon be called upon to sacrifice again in the second.

In the census taken just before the war, the town's population stood at around 500, with about 1,500 total in the surrounding region. Of that number, some 110 men joined the armed forces, about 8% of the total population—and this is almost certainly an undercount, owing to the way enlistment records were gathered at the time. Sixteen of these men never returned home from the front. In the Second World War, the story was much the same. Over 350 veterans are listed in the roll of honour, and 14 of them perished.

When looking at this humble cenotaph, it is easy to forget that behind each engraved name is a story of bravery and tragedy that is interwoven with—and helped shape—some of the most important events in modern history.

* * *

Dolly Waterman remembers the story of a Mr. Boultbee, who lived on a self-sufficient farm outside of town, more or less cut off from civilization. Remarkably, he managed to avoid hearing about the ongoing First World War until 1916, when he made a trip to town to buy supplies with two oxen. When he was told, Waterman says "He caught the first train out of town, leaving his oxen tied to a post on main street, and was never heard from again."

There were also some painful losses among some of the core pioneer families, who farmed, ranched, and ran businesses in town. These losses brought the war home to the townspeople.

Private Henry Allison, grandson of John Fall Allison, and William Herbert Lyall, brother of the prominent businessman Ged Lyall, both fell at the Battle of the Canal du Nord, only weeks before the Armistice. The battle is often described as "amongst the most impressive tactical victories of the War," and cemented the Canadian Corps reputation as the finest formation in the Allied Armies. Yet one wonders what consolation that would have been to Henry and Herbert's loved ones.

The casualties of the Second World War reflect the changed nature of Canada's war effort. Instead of fielding a large army of elite assault troops, Canada focused more on its air force and navy. Six of Princeton's 13 dead in World War II died serving in the air. One was Alexander Fernie Dickson, a gunner in one of the disastrously defective Avro Manchester bombers. He was shot down over Belgium in 1941.

Another four of Princeton's fallen fought with the Canadian army in Italy. One was Sidney Leonard Buchanan, who was killed during horrific close-quarter street fighting at the Battle of Ortona, or "Little Stalingrad" as it became known. He died on Christmas Day. Another son of Princeton, Marcel Edward Landry, fell there on Boxing Day.

The people of Princeton banded together during both wars to support their men at the front, with many volunteering for the Red Cross or contributing to the Smoke Fund set up by the Elks Club, which mailed cigarettes to men from the District.

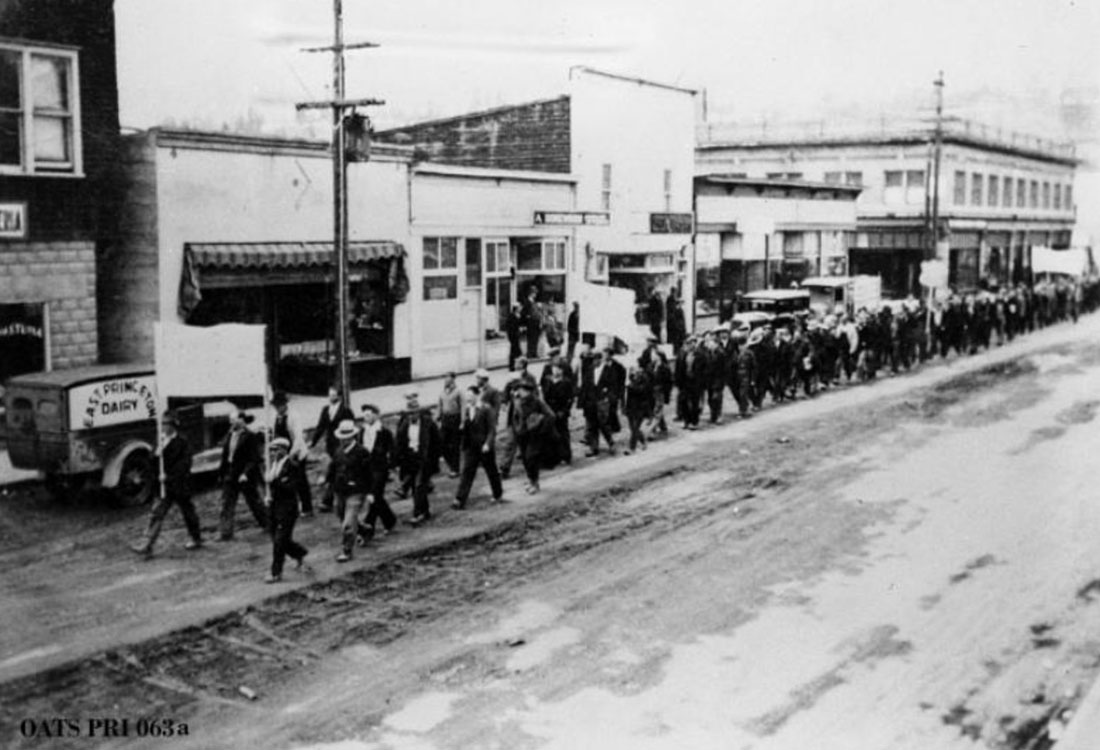

6. Soviet Princeton

Okanagan Archive Trust Society

1932

A group of striking miners marches down Bridge Street. They were men from the Tulameen mine, joined by other miners and sympathizers as they fought against a cut in wages at the height of the Great Depression. This labour dispute quickly escalated into a vicious struggle for the town's future. It was a pivotal moment in Princeton's history that was chronicled for the first time in the fascinating 2015 book Soviet Princeton, by local historians (and singers) Jon Bartlett and Rika Ruebsaat.

* * *

7. Fate of the Hotels

Princeton & District Museum Archives

1915

The substantial brick building you see on the corner here was the Princeton Hotel. It was the last and most glamorous in a succession of hotels that played a key role in Princeton's history.

When it opened in 1912, the Princeton Hotel was the only brick building in town. It boasted 40 rooms, electric lighting, indoor plumbing, and a licensed bar that would become the town's longest continuously operating bar (with the exception of the Prohibition years). Several businesses called the hotel home over the years, including the Bank of Montreal, the telephone offices, doctors' offices, restaurants, a tobacconist, a barber, a pub, and a retail liquor outlet.

* * *

Following the opening of the Hope-Princeton highway, passenger service on the train declined, and with it the hotel's business. In the early 1950s, it was renovated into suites that were rented out on a monthly basis. Sadly, the Princeton Hotel burned down in 2006, leaving a gaping hole in Bridge Street, and in Princeton's built heritage. It was a fate shared by almost all of these hotels.

8. Horse Capital of BC

Princeton & District Museum Archives

1905

A dentist's stagecoach has drawn up in front of the Hotel Jackson during the dentist's rounds from community to community in BC's interior. Before the highway or railway, horses were all-important in connecting Princeton with the outside world.

"No community in BC relied so heavily on the horse as did Princeton," writes Laurie Currie in Princeton: 100 years "Cut off from the Coast by the impenetrable Hope mountain range, the slowness of the construction of the highway to Hope, and the ruggedness of the area, the horse had a tremendous advantage over any other means of travel."

* * *

In the 1920s, Princeton local Luke Gibson became one of the most successful racehorse owners in BC, running his horses at tracks across North America. Princeton even had its own racetrack, Sunflower Downs, one of four in the interior during the height of horse racing in BC. In the mid 20th Century, horse racing was so popular in the interior that in 1965, a group of local residents and businesses fronted $100 each to fund the startup of racing at Sunflower Downs and Princeton Racing Days. In the years that followed, racing in Princeton ebbed and flowed. The track closed for a number of years before being resurrected in 2005 by members of the community who believed it was economically and culturally significant to the community. They donated volunteer hours and their own funds to rejuvenate the sport.1

Today, Sunflower Downs is a significant community facility and hosts rodeos, horse racing and training, and the fall fair. The facility also boasts a beer garden with a stage and dance floor, a race track approved for thoroughbred racing, a rodeo complex for professional rodeos, three multi-purpose buildings suitable for small gatherings, and every facility possible to support horses.

9. The Mining Economy

Princeton & District Museum Archives

1912

A huge crowd has gathered for one of Princeton's famous rock-drilling contests. In these contests, miners displayed their skills with a hand drill by seeing who could put the deepest hole in a big rock. According to one historian, these contests were "the major events of the day." It is hardly surprising that such an activity would become popular in Princeton, surrounded as it is by a constellation of mines and a number of little satellite towns to serve them.

* * *

The economic foundation of mining has had huge impacts on Princeton throughout its history. Unpredictable swings in global commodity prices can bring the town to prosperity or send it in a tailspin. In good times, people flood in looking for work, and jobs are plentiful. In bad times, people leave. Take those six nearby communities Gladys mentioned: three of them—Nickel Plate, Allenby and Blakeburn—are now ghost towns. Sometimes, people have feared that Princeton might suffer the same fate. Thankfully, however, Princeton is no longer just a mining town. It isn't going anywhere.

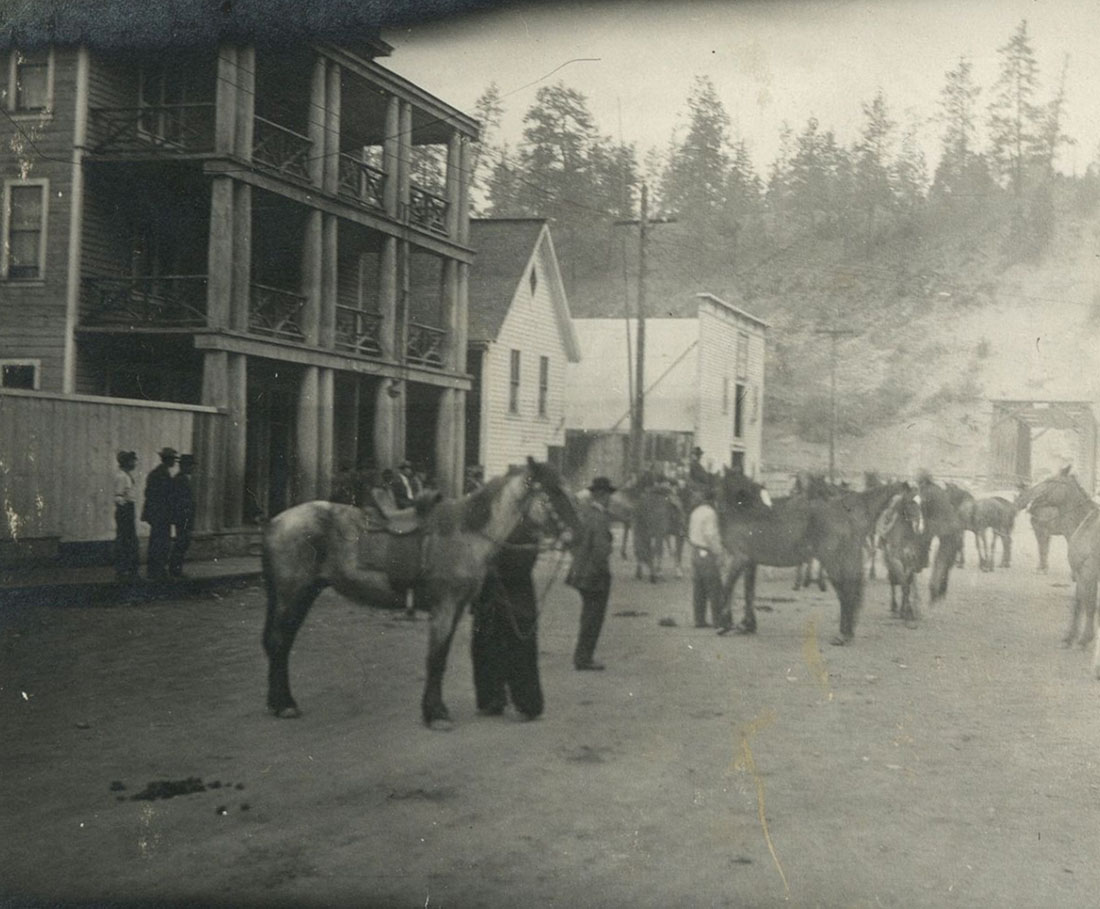

10. Boom & Bust at Granite Creek

Princeton & District Museum Archives

1908

A group of men saddle their horses in front of the Tulameen Hotel, preparing to depart across the bridge in the background. Once they crossed the bridge, they could turn to the right, along the Old Hedley Road or the Princeton Summerland Road, which was used by the Allisons as a track for herding cattle to the Okanagan in the 1860s.

If they turned left, they could follow the path of the Tulameen River, up towards the mining towns of Coalmont and Tulameen. That route also led to a town that was once the third largest in British Columbia, but has been all but forgotten for decades: Granite Creek.

* * *

Granite Creek was all but forgotten for decades, and most of the surviving buildings rotted away. It was only recently, with the tireless work of the Granite Creek Preservation Society, that this exciting chapter of BC's history was brought back to life.

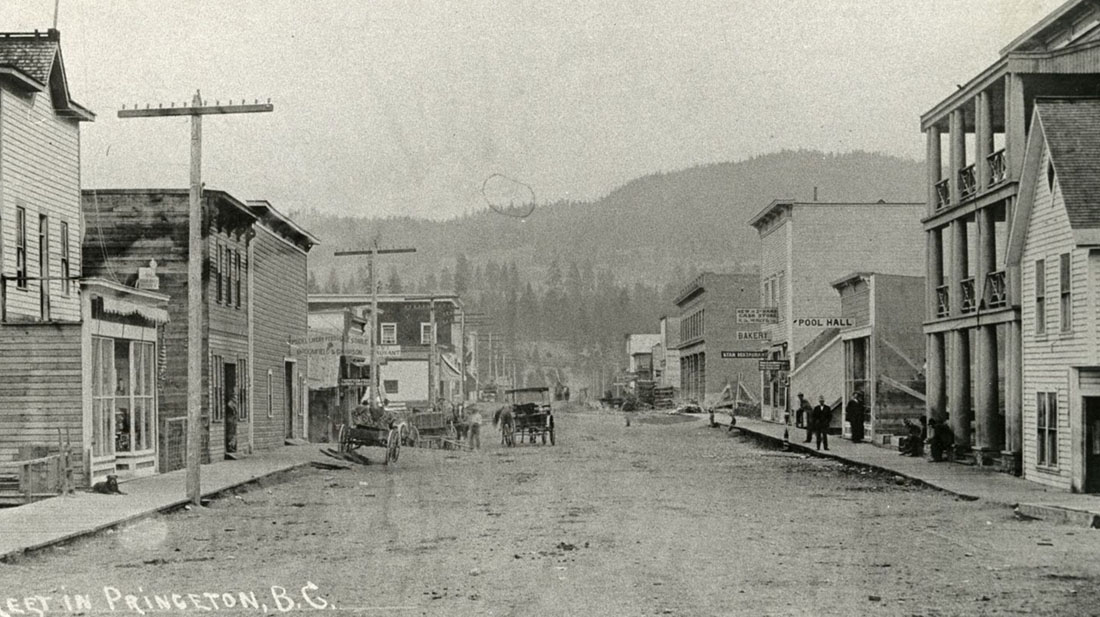

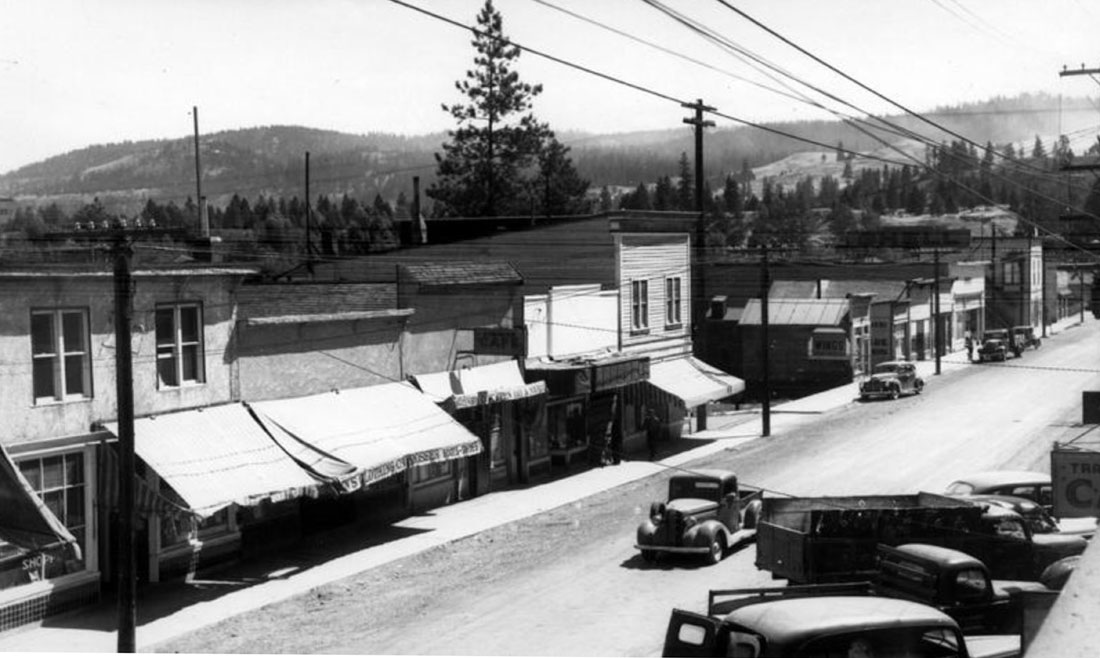

11. People from a Bygone Age

Princeton & District Museum Archives

A look down the bustling Bridge Street, showing a pool hall, bakery, hotels, general stores, and livery stables. The people who lived in Princeton at this time and frequented these businesses formed a colourful cast of characters. Everyone seemed to know everyone, and everyone seemed to have an affectionate nickname with a colourful backstory.

* * *

The social scene in Princeton was as vibrant as its residents. The Elk's Hall, on the corner behind the cenotaph, was the "Hub of Princeton life." The hall hosted many community events, along with dances that gained something of a reputation, according to one reminiscence: "I will tell you another thing. More things happened in the bush at the back of the hall than inside it."

12. From Horses to Cars

Princeton & District Museum Archives

1925

At first, this was the site of a livery stable, but by the time this photo was taken, it had become Burr Motors, a central feature of Bridge Street for decades. The switch from a stable to a garage was a sign of the changing times, as the people of Princeton retired their horses in favour of the newfangled automobiles that appeared in ever increasing numbers.

* * *

In his speech, Douglas proposed making Hope the head of steamship navigation on the Fraser River. He also intimated that he wanted to build two roads to the Interior from Hope, one north up the Fraser Canyon, the other east to the Similkameen Valley, and Princeton. Yet when the question came up of how the road would be paid for, Donald Chisholm, a political leader in Hope, balked at the idea of placing tolls on freight, while Yale representatives jumped at the opportunity. The Fraser Canyon route was built, and the Hope-Princeton road fell by the wayside.

When the road was finally built almost 90 years later, Premier Byron “Boss” Johnson ceremoniously opened the road, throwing open a padlock to the 6,000 eager motorists who had turned out for the opening. The Vancouver Sun reported on the occasion: “As the padlock sprang open in the Premier’s hands, he declared the $12 million Hope-Princeton Highway officially open… Cars drove over the new stretch of blacktop highway which will lop 100 miles off the distance from the South Okanagan to Vancouver. The road, conceived more than 100 years ago, is the last link in the 713-mile highway which stretches across the province.”1

While the road was significant for residents of the southern interior, it was built with a high human cost, as well as a financial one. The road was built largely with the unpaid labour of interned Japanese-Canadians during the Second World War. Following the attack on Pearl Harbour, the Canadian government shipped thousands of Japanese-Canadians inland away from the coast, where it was feared they would pass information to Japan—despite many of them never having even been to Japan. The labour was brutal. Without mechanized equipment, the interned Japanese-Canadians dug the foundations of the road by hand, using picks, shovels, and wheelbarrows. This contribution went unrecognized until September of 2018, when a sign was finally placed on Highway 3 in remembrance of one of these road camps.

13. A Love of Sport

Okanagan Archive Trust Society

1929

Members of the PSC, the Princeton Ski Club, pose in front of the Thomas Bros. General Merchants store. They've got their cross-country skis on and are probably heading for an outing at the "A" Hill overlooking Princeton. The club was formed by a core of Norwegians and Swedes who lived around Princeton in 1924 and was led by the legendary Norwegian Andy Stenvold. They brought their love of ski jumping from Scandinavia and erected great jumps at the local hills, which attracted some of the world's foremost ski jumpers.

* * *

A fervent rivalry with surrounding mining towns contributed to the intense sporting culture in Princeton. Princeton competed against Hedley, Keremos, Blakeburn and Copper Mountain, with baseball being the most popular sport prior to World War II. The Princeton Royals (named after a local brew) reigned supreme, winning 63 games and losing only nine during a three-year period. The rivalry was so intense that one Hedley man, G. McGonigle, the manager of the Hedley Gold Man, "imported an entire baseball team from Vancouver just so he might beat Princeton. In a July 1st game, played on the old Wallace field, over $1000 changed hands. Princeton won."

As Laurie Currie writes in Princeton: 100 Years, "No other community in the province can boast of a more diversified sporting area than Princeton."

He is surely right.

14. To Incorporate?

Okanagan Archive Trust Society

1945

A view of the east side of Bridge Street in the 1940s, showing how many of the empty lots from earlier decades have been filled in and how the community has grown substantially.

By this time, Princeton was outgrowing its pioneer roots, which led to fierce debate about the community's future. Princeton's history as a mining town had created a peculiar situation: for decades, it had never been incorporated as a town or even a village. This meant there was no municipal government, and negligible municipal services, which led to an unpleasant article in 1930 that referred to Princeton as the "dirtiest hole in the Interior."1

* * *

Over time, pressure built. After World War II, the decades-long fight over incorporation reached a crescendo. Various attempts to incorporate over the years had failed, but with the completion of the Hope-Princeton highway, it could no longer be avoided. Finally, in 1951, a vote was held and Princeton incorporated as a village. The first chairman was incorporation's fiercest advocate, the redoubtable miner's son: Isaac Plecash.3 Princeton's days of being the "dirtiest hole in the interior," were in the past.

15. Looking Back

Princeton & District Museum Archives

ca. 1900s

A man with his hands thrust in his pockets mugs for the camera. Behind him, Bridge Street is largely empty, save the headquarters of the Similkameen Star, which we saw earlier on in the tour. Photos like these remind us of the dramatic changes Princeton has undergone, and the people who have made it what it is today.

Endnotes

2. Vermilion Forks

1. Princeton History Book Committee, *Princeton Our Valley: A History of Princeton, Allison Pass, Tulameen, Stirling Creek, Aspen Grove, Osprey Lake, Copper Mtn, Darcy Mtn, Allenby, Blakeburn, Coalmont*, (2000), 12.

4. The Gentleman Bandit

1. .Edward Butts, "Mill Miner," The Canadian Encylopedia, January 18, 2019. Online.

6. Soviet Princeton

1. Jon Bartlett & Rika Ruebsaat, *Soviet Soviet: Slim Evans and the 1932-33 Miners' Strike*, 2012, 1.

7. Fate of the Hotels

1. Okanagan Historical Society, "Okanagan History: Seventy-First report of the Okanagan Historical Society," (Vernon BC: The Okanagan Historical Society, 2007), 101.

8. Horse Capital of BC

1. Gary Bannerman, "Horse racing in the North Okanagan: Historic Kin Horse Park and the future," Proposal prepared for the Okanagan Equestrian Society, October 9, 2007, Appendices.

10. Boom & Bust at Granite Creek

1. "Ghost Towns: Granite Creek Cemetery," *Talkdeath*, 4 January 2016, online.

12. From Horses to Cars

1. John Macke, "This Week in History, 1949: The Hope-Princeton Highway opens," *The Vancouver Sun*, Nov. 2, 2019, online.

14. To Incorporate?

1. Laurie Currie, 73.

2. Laurie Currie, 73.

3. Laurie Currie, 73.

Bibliography

Bannerman, Gary. "Horse racing in the North Okanagan: Historic Kin Horse Park and the future," Proposal prepared for the Okanagan Equestrian Society, October 9, 2007. Appendices. https://coldstream.civicweb.net/document/524

Bartlett, J & Ruebsaat, R. *Soviet Soviet: Slim Evans and the 1932-33 Miners' Strike.* New Star Books, 2015.

Butts, Edward. "Mill Miner." *The Canadian Encylopedia.* January 18, 2019. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/william-miner#:~:text=Bill%20Miner%20was%20reputed%20to,outlaw%20hero%20in%20Canadian%20folklore.

Macke, John. "This Week in History, 1949: The Hope-Princeton Highway opens." *The Vancouver Sun*, Nov. 2, 2019. https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/this-week-in-history-1949-the-hope-princeton-highway-opens

Okanagan Historical Society, "Okanagan History: Seventy-First report of the Okanagan Historical Society." Vernon BC: The Okanagan Historical Society, 2007.

Princeton History Book Committee. *Princeton Our Valley: A History of Princeton, Allison Pass, Tulameen, Stirling Creek, Aspen Grove, Osprey Lake, Copper Mtn, Darcy Mtn, Allenby, Blakeburn, Coalmont*. 2000.

Talkdeath. "Ghost Towns: Granite Creek Cemetery." 4 January 2016. https://www.talkdeath.com/ghost-towns-granite-creek-cemetery/