Originally located primarily on the shore of Okanagan Lake, the town of Summerland first began to be settled in the 1890s, when the land first opened to preemption by white settlers. For millennia, the region has been home to the Syilx Okanagan First Nations, who first had contact with Europeans in 1811, when fur traders passed through the Okanagan. The Syilx took part in the fur trade through the trading of horses for European goods. Eventually, the fur trade faded away and more permanent European settlement took place in the South Okanagan, as cattle ranchers and orchardists moved to the area. Summerland's first post office opened in 1902, and the town developed rapidly from then on, aided by the investment of the Summerland Development Company, owned and operated by men such as Canadian Pacific Railway president Thomas Shaughnessy and real estate developer J.M. Robinson. Throughout the early twentieth century, the town underwent a gradual shift away from the water to a new townsite. Today, the community's main street is located two kilometres from the water, though the waterfront remains a popular part of the town.

This project was made possible through a partnership with Visit South Okanagan and Visit Summerland.

We respectfully acknowledge that Summerland is within the ancestral, traditional, and unceded territory of the Syilx People of the Okanagan Nation.

Explore

Summerland

Stories

Summerland's Early Days

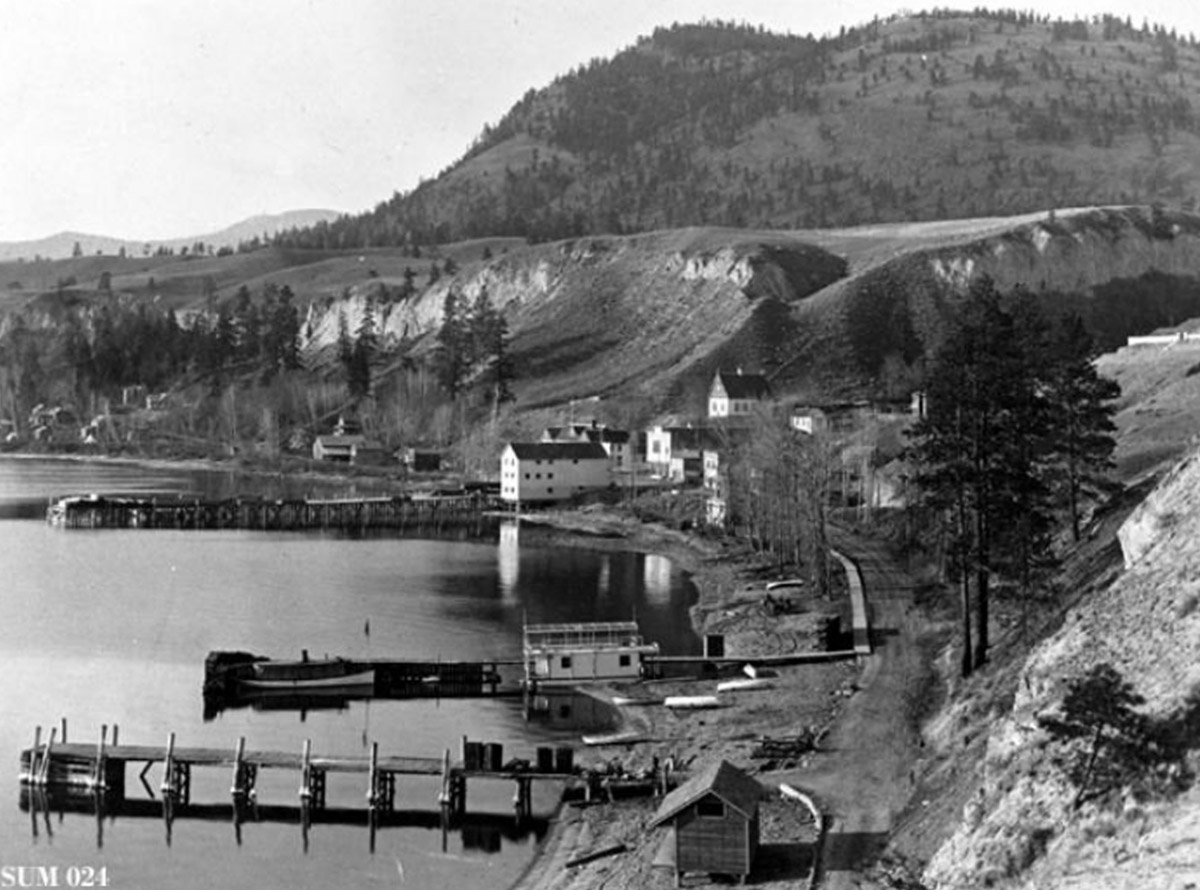

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 024

Before the town of Summerland existed, the local Syilx Okanagan First Nations people lived here for thousands of years, living sustainably off of the land and developing complex trade routes within their own nation and beyond.

The first Europeans in the area were fur traders passing through the region in 1811. From then on, the European presence grew at a gradual yet increasingly disruptive pace. In fact, local First Nations people were affected by Europeans long before the first fur trader came to the area—smallpox epidemics swept through the area in 1775 and 1781, brought to the region through Indigenous trade routes.1

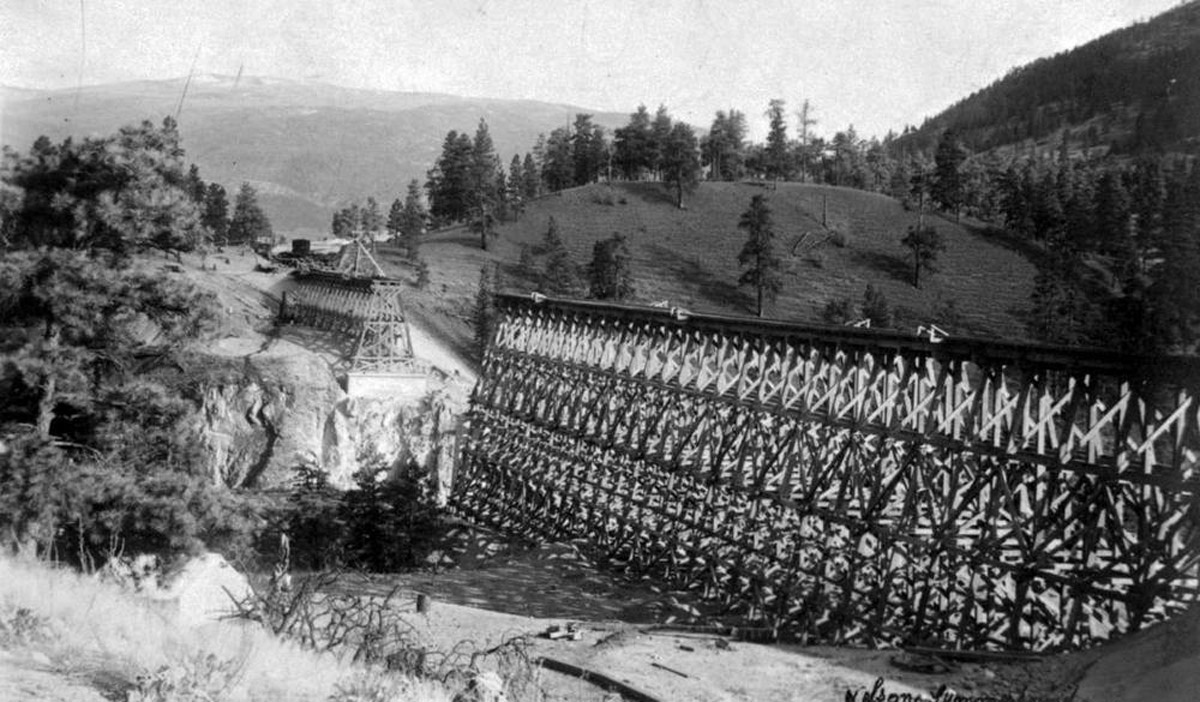

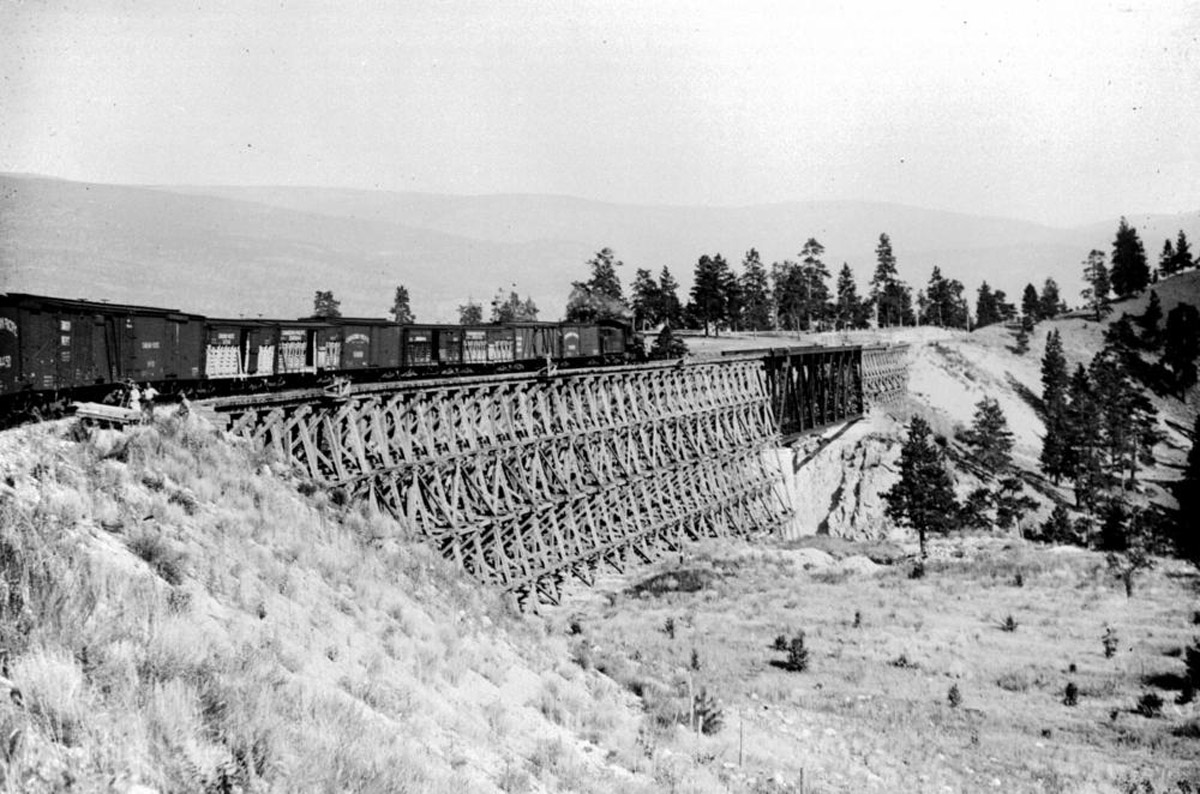

The Coming of the Railway

In the beginning of European settlement in the South Okanagan, transportation was difficult and time consuming, limited to either long journeys by horse and foot or infrequent boats across the waters of the lake. While semi-regular steamship service was first launched in the Okanagan Lake in 1893 with the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) vessel the SS Aberdeen, rail transportation was a much more complicated issue.

The Science of Agriculture

In the South Okanagan, agriculture has always been key to settlement. The first Europeans who settled here on a long-term basis were ranchers who raised hundreds of head of cattle on their vast land holdings. These gradually gave way to orchardists, who came from all over the world to grow fruit in the warm climate of the Okanagan. Fruit trees spread across the land, and each town was home to several packing houses to prepare crops for sale.

Yet as prosperous as fruit growing is in the South Okanagan, it also comes with immense challenges, and at no time was this more true than at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries, when fruit growing was first beginning in the valley. Winter temperatures froze the region, codling moths destroyed crops during an epidemic in 1925, irrigation systems were difficult to build and maintain, and both equipment and knowledge was minimal.1

Advancements in agronomy made at the Dominion Experimental Farm would be required to jumpstart the Okanagan agricultural powerhouse.

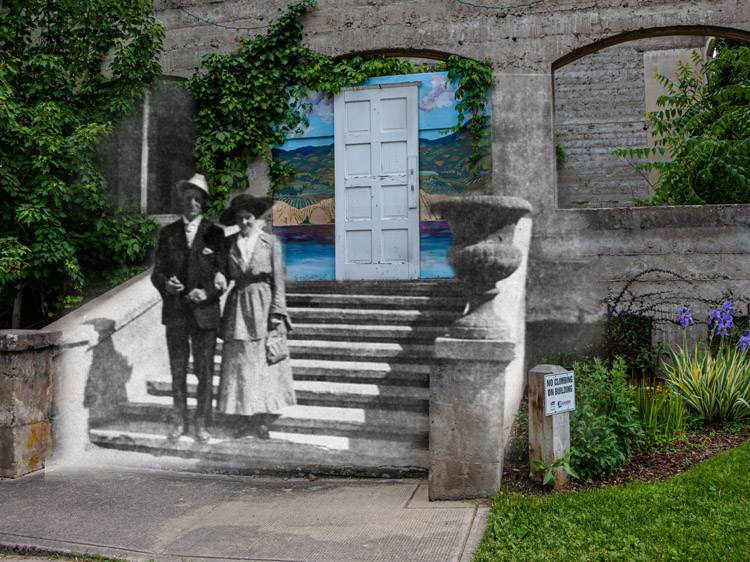

Then and Now Photos

A View of Summerland's Waterfront

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 065

1910

This photograph from 1910 was taken from Solly Road and looks down over the original Summerland townsite beside the waterfront. The white house on the right side of the image belonged to J.M. Robinson, a key real estate developer in the town. Also visible is the church, in the center of the image, and the Canadian Pacific Railway wharf to the left.

Rosedale Road

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 070

1910

This photograph from 1910 looks southeast down Rosedale Road towards Giants Head. The street is brand new, still more of a mud track than a road.

Main at Victoria

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 010

1930

The building on the left side of this photograph of Main Street and Victoria Street still remains standing. The road remains unpaved in this photo, but horses have been replaced by early automobiles.

A Vista Over The Lake Shore

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 016

1930

This photograph from 1930 shows Summerland's lower town clearly. The CPR wharf is to the left, along with a corner of the fruit packing house. Lakeshore Drive is straight ahead, quiet and without cars after the townsite shifted away from the lake to the west during the 1920s.

A Red Cross Event

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 075

1942

In this photograph from 1942, a group of kids march in uniform across the school yard as part of a Red Cross event during the Second World War. The church is visible in this photograph in the background at center left.

A War Time Rally

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 078

1942

This war time rally took place in 1942, during the Second World War. In this photo, the children of the school are gathered in a large crowd on the school grounds with their parents standing on either side. The packing house is in the background of the photo.

Construction of the School

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 026

1951

This high school was constructed in 1951, the year this photograph was taken. Previously, high school had taken place in a small four-room schoolhouse, but a growing population necessitated the construction of this new building.