For millennia, this land has been the traditional territory of the Syilx People of the Okanagan Nation, who lived sustainably off the land, fishing, hunting, foraging, and developing complex trading networks across the region and beyond. Europeans first came to the area in 1811 as part of the fur trade, and settlement by white farmers began soon after. In its early days, Naramata had many names: Nine Mile Point, East Summerland, and Brighton Beach. The town was founded in 1907 by real estate developer John Moore Robinson, who had previously laid out the towns of Summerland, directly across the water, and Peachland. Robinson clearly fell in love with Naramata, as he chose it as his permanent home, but it took him a while to settle on a name for the community. In the end, "Naramata" was chosen, though there are many different stories as to why, one of which claims that the name came to Robinson during a séance. Once established, the town grew into a small, thriving farming community. The school was opened in 1907, and the historic Naramata Hotel, owned by Robinson, in 1908. Today, the Naramata Bench is covered in lush vineyards, and fruit trees still grow in Naramata's plentiful orchards. The Kettle Valley Railway hiking and biking trail brings visitors to the community all summer long.

This project was made possible through a partnership with Visit South Okanagan, with support from Discover Naramata.

We respectfully acknowledge that Naramata is within the ancestral, traditional, and unceded territory of the Syilx People of the Okanagan Nation.

Explore

Naramata

Stories

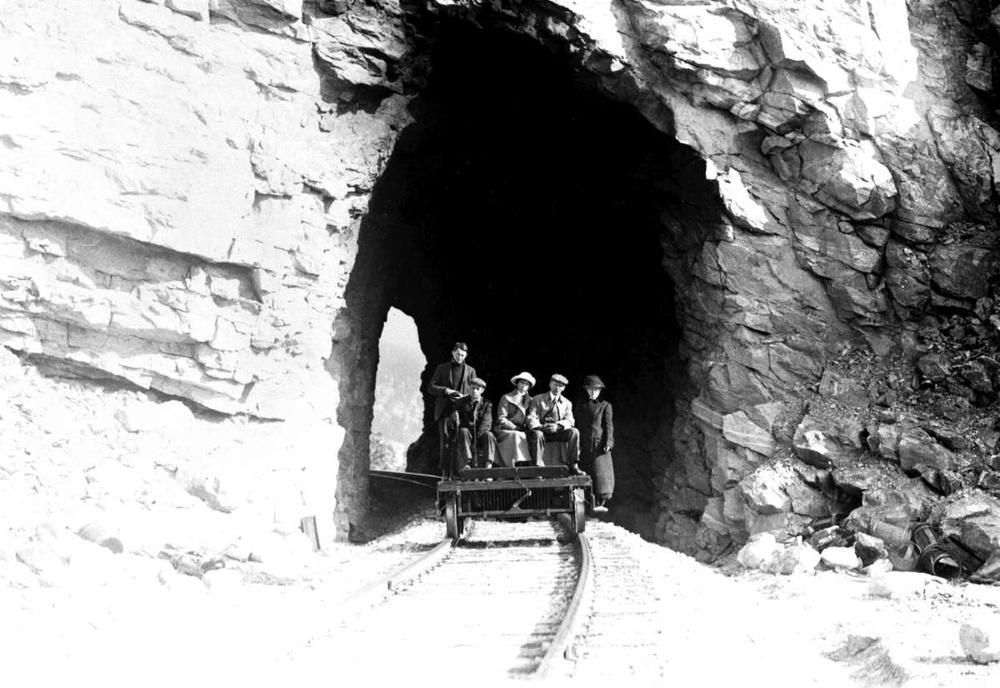

The Kettle Valley Railway and Naramata

The "Little Tunnel" outside Naramata is one of the highlights of the famous Kettle Valley Rail (KVR) Trail. When the trail was still a railway, it ran north towards Naramata from Penticton and passed Naramata a little above the community. While the railway is long gone, evidence of its construction still remains.

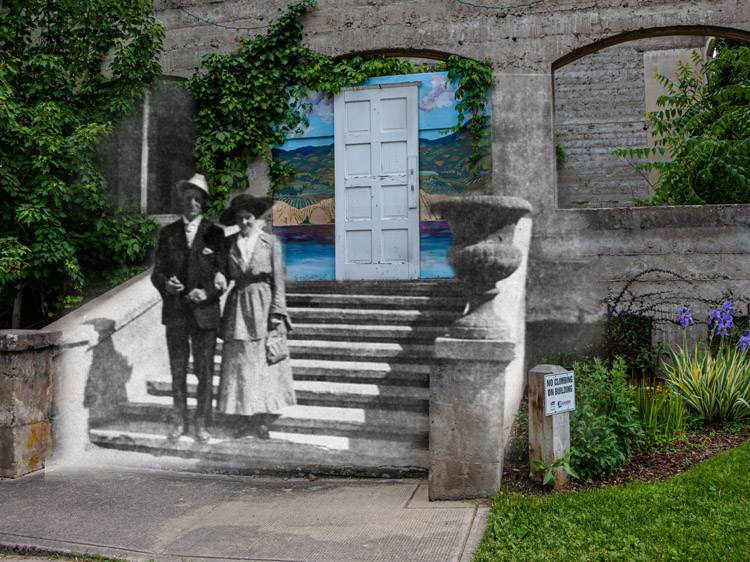

The Story of J.M. Robinson

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 030H

No figure looms larger in the history of the central Okanagan than eccentric entrepreneur John Moore Robinson. This man founded not only Naramata, but Peachland and Summerland as well. Naramata was the last community established by Robinson, and where he ultimately chose to settle down.

The name Naramata was the last in a long line of names applied to this site on the eastern side of Okanagan Lake. Settlers first deemed it the unimaginative moniker "Nine Mile Point" for its location nine miles north of Penticton. Robinson then named the area East Summerland as it was across the lake from Summerland. Then, he changed his mind and renamed it "Brighton Beach" after a beach in New York City where he had received his education. This name must’ve not been original enough for him, because the name was then changed one final time. There are several legends around the origin of the name. Allegedly, Robinson himself told people that he had come to the name during a seance where the town's medium, Mrs. Gillespie, channelled an unnamed "Indian Chief" who spoke of his wife Narramattah. Regardless of whether this story is true, the name finally stuck and Brighton Beach would forever be known as Naramata.1

Naramata Agriculture

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 079

Like much of the Okanagan, before Robinson’s dream of blooming orchards could be achieved, the land had to have irrigation systems set up. J. M Robinson, Naramata founder and ambitious entrepreneur created the Naramata Irrigation Company to build the water delivery system. The company earned back its investment through charging the orchards for the water.

Then and Now Photos

The Maude Moore at Dock

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 108

1906

Originally built by W.J. Snodgrass of Okanagan Falls to run on Skaha Lake, the ship the Maude Moore, seen here at the government dock in Naramata, was purchased by Naramata founder J.M. Robinson in 1905. She served as a ferry between Naramata and Summerland until 1911.

Naramata Supply Company

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 043

1907

The wooden building to the right of this photograph is the Naramata Supply Company, owned by J.M. Robinson, who founded the town of Naramata. The empty area in the background of the photo is now the site of the historic Naramata Inn, which was also built by Robinson.

Boats at Dock

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 107

1907

In this photograph, two of J.M. Robinson's boats are docked at the wharf in Naramata. The Lily of the Valley is to the left, with a crowd of people aboard, while the Maud Moore is to the right.

A Canoe Team

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 084B

1910

This photograph shows a group of Naramata citizens in a canoe near the lake shore. The canoe team is mixed gender, with four women and three men.

The Grand Stand and Hotel

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 028

1912

On the left of this photograph of First Street in Naramata is the grand stand, used to watch the community's popular regattas. The Naramata Hotel is beside the stands. Naramata held its first regatta in 1908, and the sporting event became so popular that the 800-person grand stand was built soon after, though it burned down just a few years after completion.

A Cricket Team

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 077C

1950

This cricket team, posing for a team photo in 1950, was playing in the Cricket Champions in Manitou Park. They clearly did well, as is evidenced by the large trophy displayed in front of them.

Riders at the Naramata Hotel

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 033A

1941

Two young girls ride in front of the Naramata Hotel in this photograph from 1941. The hotel was the first building in the town to have running water and electricity for its lights. It even had a basic telephone connection to the Naramata Supply Company building.