The Black history of Oxford County begins with the early settlement of the area in the nineteenth century. Before the 1830s, free Black families were moving from the northern United States to southwestern Ontario where they could find work, buy farmland, and settle in security. In the middle of the nineteenth century Ingersoll was a terminal for the Underground Railroad, and abolitionist John Brown stayed in the town in 1858. In Oxford County, communities were established in Ingersoll, which was second in southwestern Ontario only to Chatham in the size of its Black community in the mid-1800s, and in Norwich Township alongside the Quaker settlement. Many residents of Norwich had opposed the enslavement of Black people long before they emigrated from the United States to Canada themselves. Following the first known Black landowner in Norwich, Samuel Jones, in 1833, the community grew.

This project was funded by the Canada Healthy Communities Initiative in partnership with several of the area’s museums, archives and public historians.

We would like to acknowledge the history of the traditional territory on which Oxford County stands. We would also like to respect the longstanding relationships of the local Indigenous groups, the Haudenosaunee, Lanape, and Anishinaabek of this land and place in Southwestern Ontario. We would like to recognize the Indigenous communities in close proximity to Oxford County: Chippewas of The Thames First Nation; Oneida Nation of The Thames; Munsee-Delaware Nation; Mississaugas of New Credit First Nation; and Six Nations of The Grand (which consists of Mohawk, Cayuga, Seneca, Onondaga, Oneida and Tuscarora Nations).

Explore

Oxford County

Stories

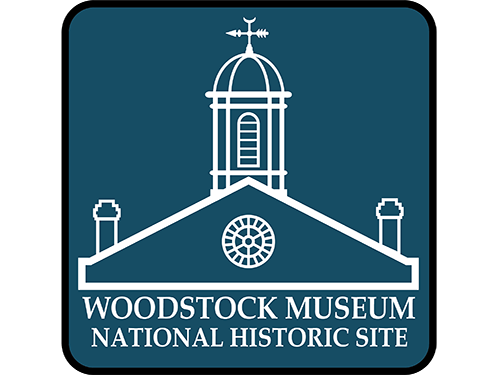

Otterville African ME Church & Cemetery

The Otterville African Methodist Episcopal Church was constructed on the outskirts of Otterville by 1856. This structure became the centre for large church camp meetings attended by both Black and white people from the surrounding area. Often the visiting Black minister preached in the Otterville Methodist Church. In 1856, the AME Church in Canada split from its prdecessor in the United States and was renamed the British Methodist Episcopal Church, in order to give it a more Canadian identity. Surrounding the site of the former church is the cemetery, which was restored by the South Norwich Historical Society in 2007.

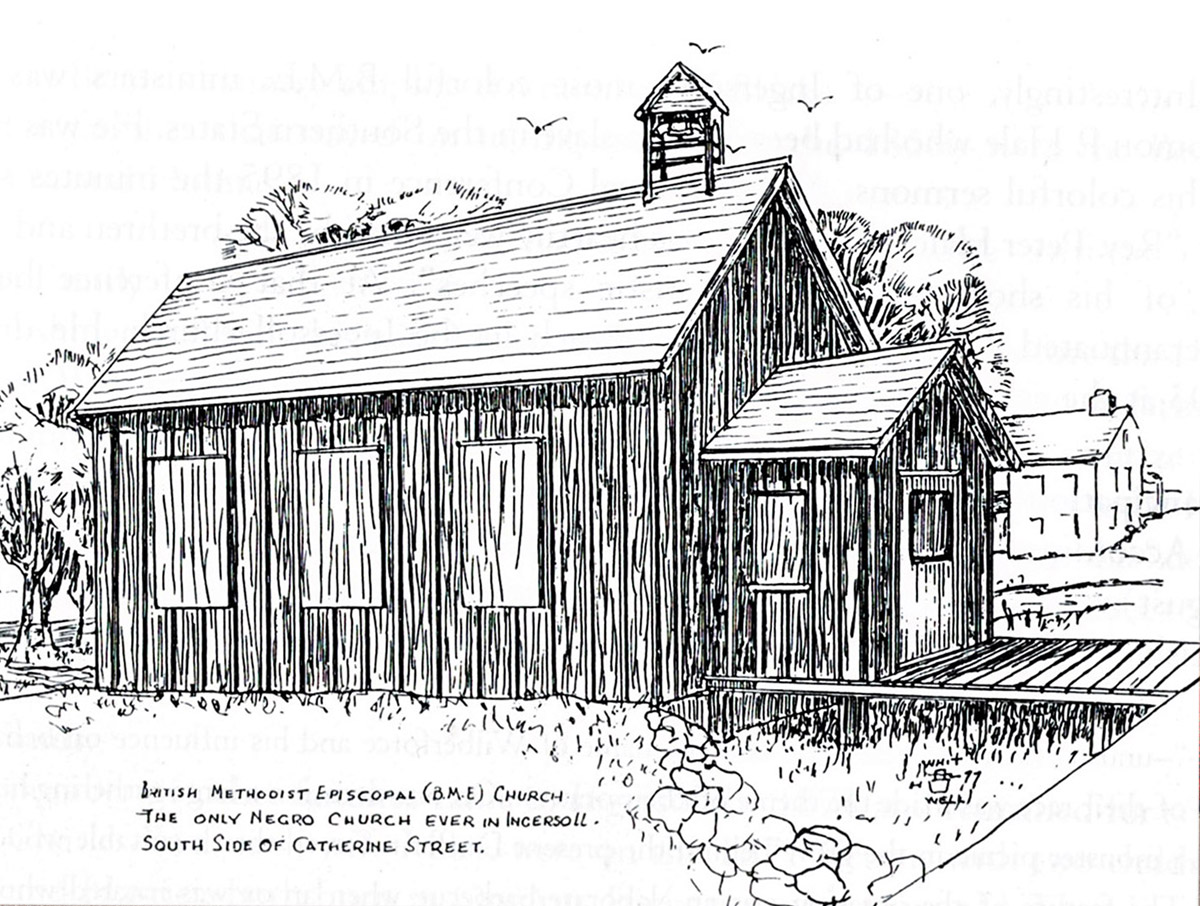

Ingersoll BME Church

The large population of Black Ingersoll residents wanted their own church, and so they built the British Episcopal Church (BME) in 1858. Also called the “Negro Church”, the BME Church was erected on the south side of Catherine Street on the east side of the stream, located near where the majority of Black people in Ingersoll had lived. In addition, many Black people were buried in the Ingersoll Rural Cemetery as well as in Potter’s Field. The Church was built like a barn, with vertical board and batten siding and three large windows to let in light. Reverend Solomon Peter Hale was the last Minister of the BME Church; he died in Ingersoll in 1904. In 1933, the BME Church was sold to R. Cuthbert of Sweaburg who demolished the building and used the lumber to build a hog pen. Few known photographs of the BME Church exist.

Frederick Stover

One of the first settlers in Norwich in 1811, Frederick Stover (1770-1857) was an arch proponent of Black settlement in the Norwich area. Born in Dutchess County, New York, Stover came to Norwich Township with much of his extended family. He owned land on what is now Quaker Street, on which he built a farmstead, as well as donating twenty-five acres of land for the construction of a Meeting House, on which this cemetery now stands. Stover, a Quaker, became an abolitionist on his travels to the Yearly Meetings of the Society of Friends in the United States in the 1830s. Stover was appointed to purchase the land for the Wilberforce settlement in 1830, having corresponded with the Indiana Yearly Meeting’s Standing African Committee.

Ingersoll Cheese Museum

Ingersoll Cheese Museum & Archives

Ingersoll, located in the heart of Southwestern Ontario in Oxford County, was incorporated on January 1, 1852. In the mid-1800s, the size of Ingersoll’s Black community was second only to Chatham in the region. Of the town’s 2,000 residents, 400 were Black. The Ingersoll Cheese & Agricultural Museum was first opened on August 27, 1977, consisting of a re-creation of a 19th century cheese factory. A former barn had been dismantled and the pieces moved to Centennial Park, where they were re-assembled in the shape and design of a typical cheese factory in Oxford County.

Marshall Anderson

Woodstock Museum NHS 1988.32.2

Born in Summerville, Norwich Township, in 1845, Marshall Anderson was the son of Hannah and Rev. Lindsay B. Anderson, a preacher at the British Methodist Episcopal church in Otterville. Marshall married Sarah Turner with whom he had a daughter, Frances, ca. 1863. When Sarah died young, Marshall married her sister, Mary, with whom he had two children, Ernest and Maud. The family moved to Woodstock in 1880 after the death of Sarah and Mary’s mother, Mary Turner. The younger Mary, Marshall’s wife, died in 1881.

Milldale Burial Grounds

While many of the Black families in Norwich Township attended the Otterville African Methodist Episcopal church, others chose to attend different churches. Robert (pictured above, left) and Harriet Williams (right) are buried in the Milldale Burial Grounds, a Friends (Quaker) burial ground associated with the Milldale Meeting. Robert and Harriet attended this meeting in their later years.

Norwich & District Historical Society

Norwich Museum & Archives 1485

The town of Norwich was founded in 1810 by settlers from Dutchess County, New York, many of whom were members of the Society of Friends (Quakers). By the 1830s, these Quaker settlers began to encourage free Black people from the United States to move to Upper Canada. Of these Quakers, Frederick Stover was of particular importance. He became involved in abolitionism as he travelled to Quaker Yearly Meetings in the United States, and was involved with the establishment of the Wilberforce settlement.

Other Norwich Quakers were involved in the abolitionist movement, including town co-founder Peter Lossing. As the dowry from his first marriage, Lossing was offered a number of enslaved people; on receiving these people as property, he not only freed them but helped the adults find work, and the children find new homes. The Norwich and District Museum is housed in one of several Quaker Meeting Houses built in Norwich. This one was constructed in 1889. This building was sold to the Norwich and District Historical Society in 1968 for $1.00 so that it could serve as a permanent museum site, a function it serves to this day.

Otterville Cemetery

The Otterville Cemetery was established in 1892 with no church affiliation. It is the resting place of many Black people who lived in Otterville, including Ida Gray, the only granddaughter of Robert Williams Sr. and Harriet Cooley Williams, and her father, Benjamin Gray.

Otterville Mill & Station Museum

The Otterville Mill and Station Museum stands on the site of the Pine Street Quaker Meeting House. Many of the Quakers at Pine Street were ardent abolitionists involved with their fellow Quakers in New York State. William Cromwell, who came to Otterville from Canandaigua, New York, was a particularly ardent abolitionist. He was financially involved with the Otter Creek Mills, and seems to have been the reason why the free Black families that migrated from the United States established themselves a mile north of the mill. While most of these Black settlers had the wealth to buy land in Otterville and establish successful farms, those who were not farmers could find work at Cromwell’s mills.

The Pine Street cemetery is the resting place of several prominent Black members of the Otterville community. Those buried here include Rev. Lindsay B. Anderson, one of the founders of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

The Marshall Family

Woodstock Museum NHS 2009.8.32

Thomas George Marshall was one of the oldest sons of Thomas and Mary Elizabeth Marshall, born in Dunville, Ontario, around 1870. Charlotte Ann Martin was born ca. 1880 to Joseph Martin and Emily Campbell in Dereham Township. Thomas George and Charlotte married in 1902. They lived at 226 Oxford St. in Woodstock. The house, which still stands today, is on a corner lot just across from the site of the Old Thomas Organ factory and the Stewart Brothers Foundry at Brant Street. Thomas George’s parents lived at 222 Oxford and his uncle at 224. Most of the men in the family worked as labourers at either of the two factories. Thomas George himself worked at the Stewart Foundry for many years until his death in 1952. Besides working at the Organ factory, the family was very musical, and the children learned a variety of different instruments.

George Washington Jones

Woodstock Museum NHS 1968.48.1

George Washington Jones was born into slavery in the United States around 1856 and escaped in a boxcar to Canada. He came to Woodstock in 1925 as part of a travelling carnival and decided to stay. Being friendly and outgoing, and with his huge smile, he became everyone’s friend. Wearing a top hat, a long coat with tails, striped pants, a sandwich board, and carrying a megaphone or bells, he appointed himself town crier. Business, theatre and restaurant owners purchased space on the board, and he advertised sales and events.

Woodstock BME Church

Woodstock Museum NHS 2008.17.89

As the Black population in Woodstock slowly grew, the need for a church arose. The movement to build a church began around 1883 by George Washington, a porter, and Dan Anderson, a stonemason. After raising funds from the community, they purchased a lot on Park Row and started construction in 1888. Throughout its history the church was known by three names: Hawkins Chapel, British Methodist Episcopal Church, and Park Row Community Chapel. At its height, the church ministered to 75 Black families. Reverend H.H. Clarke once stated that there were no colour lines at the church, and that anyone, regardless of race, was welcome to attend. The church operated from 1888 to 1972, re-opened in 1978 and then was closed permanently and sold in 1985.

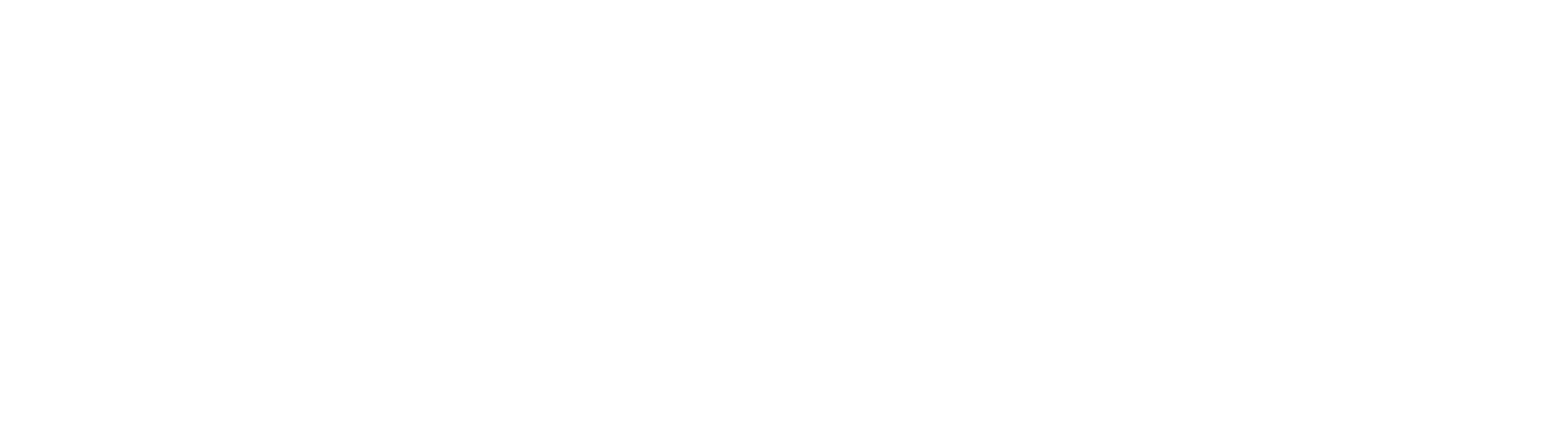

Woodstock Museum NHS

The Woodstock Museum National Historic Site strives to interpret the past, present and future through conservation, education and exhibition of local history.

Visit the nationally designated Old Town Hall and experience the original 1879 Council Chambers and the Victorian designs of the 1889 Grand Hall. Tour the galleries interpreting the History of Woodstock from the 1790s to the present day.

Originally constructed in 1853 as the Town Hall and Market House, the building was completely restored in 1993 – 1995 and offers a wide variety of programs and services.

Daly House

Ingersoll Cheese Museum & Archives

The Daly House was also associated with the Underground Railroad. Located at the corners of King Street West and Oxford Street, legend had it that a tunnel joined the Wesleyan Methodist Church to the Inn. It was said that those escaping their enslavement by hiding in the Church could be brought out through the Daly House by way of this tunnel. However, when the former hotel was demolished in 1994, no traces of a tunnel could be found. The Daly House is also where John Brown stayed when he visited Ingersoll in 1858, awaiting Harriet Tubman, who did not arrive.

Kirwin House

Ingersoll Cheese Museum & Archives

"First known as the Chamber Hotel, then Oxford House and then later known as the Kirwin House, it was built in 1891-92 on Oxford Street, west side, opposite the old Market Building (municipal parking lot). It served Ingersoll until 1967, when it was torn down for a new modern building (presently the Oxford Small Business Centre). It was a farmer’s hotel with auction yards and there were stalls for the cattle to wait in before they were sold across the road. The farm implement dealer, W. J. Fishleigh would put on dinners for his perspective buyers at the Kirwin Hotel."

- Excerpt from Ingersoll: Our Heritage by Harry Whitwell.

The Old Brick Meeting House

Norwich Museum & Archives 0175

In 1847, the Norwich Quakers assembled a committee to raise money for the purpose of constructing a new meeting house. Having met in a frame building on the hill by the old burial ground (the Norwich Pioneer Cemetery, also on Quaker Street), the Norwich Friends required a more substantial building in which to hold their meetings. Twenty-five acres of land for the new building was acquired from Frederick Stover, of which nine and a half were sold to pay for its construction. It was completed in 1850 and became known as the Old Brick. Therefore, it was while this meeting house was in use that much of the local Quaker activities to encourage the settlement of Black people in the Township occurred. The Old Brick was demolished in 1949, but the cemetery continued in use for many years.

Wesleyan Methodist Church

Ingersoll Cheese Museum & Archives

The Wesleyan Methodist Church on Oxford Street in Ingersoll was built in 1854 by residents of the town who had formerly been enslaved in the United States. It is said to have been the northernmost terminus of the Underground Railroad in this part of Southwestern Ontario. The Church consisted of a three-storey brick building which could seat five hundred people, with living quarters for the minister on the top floor. Pine boards in the attic measured twelve to fourteen inches wide, which indicates the size of white pine trees that inhabited Oxford County then. Led by Quakers by the way of St. Thomas, Black people escaping enslavement in plantations in Virginia, Georgia, Louisiana, and even as far as New Orleans, were smuggled into the attic of the Ingersoll Church during the night. Others were brought here as part of a stage couch operation from Port Burwell by abolitionist Harvey C. Jackson, who made regular trips inland to the Daily House Hotel. Opponents of slavery would try to find work for them on neighbouring farms throughout Oxford County, or would transport them to other areas to work, to enable them to safely reach their destinations.