Partner City

Aylmer

Standing the Test of Time

The land that Aylmer now sits upon has been the traditional territory of the Attawandaron (or Neutral Nation), Anishinaabe, Mississauga Nation, Haudenosaunee (or Iroquois Confederation), and their ancestors since time immemorial. Their story is told through oral histories and was unearthed at archaeological sites in the area. At the Pound Site, an Attawandaron settlement dating from the Woodland Period, some 3,000 years ago, archaeologists uncovered the remains of at least one burned longhouse and a unique type of pottery which was named after the site. Europeans first began to settle the area around Aylmer in the 1810s, and by the 1830s a village was taking shape. In the ensuing decades the community developed into a service centre for the surrounding farms. The pace of growth quickened following the arrival of a railway in 1873. Capital poured in and the late Industrial Revolution took off in Aylmer. Soon the town boasted mills, a foundry, a pork-packing house, a milk evaporating plant, and a shoe factory. The town attracted workers for these growing industries, and the population continued to increase rapidly into the early twentieth century. Agriculture also remained a key component of the local economy, and Amish and Mennonite farmers established strong communities in the region. A training airfield was established nearby during World War II, which later became the centre of the Ontario Police College.

This project is a partnership with the Aylmer-Malahide Museum & Archives.

We respectfully acknowledge that Aylmer is on the traditional lands of the Haudenosaunee, Anishinabewaki, Attawanderon, and Mississauga Credit First Nations, the land's keepers and defenders.

Walking Tours

Aylmer's Industrial Past

Labour and Industry

A Jaunt Down Talbot Street

Walking Through Aylmer's History

Explore

Aylmer

Stories

The Ontario Police College

Aylmer-Malahide Museum & Archives

The compound pictured here was originally home to the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) training school and now houses the Ontario Police College. In its early days, the complex consisted of fifty buildings, five hangars, and three runways.1 The Province of Ontario took over ownership of the grounds in 1962 in order to use the space for the Ontario Police College. In 1971, the complex was renovated to better serve modern training.2

Canada Southern Railway

Aylmer-Malahide Museum & Archives

Completed in 1873, the Springfield Railway Station on the Canada Southern Railroad increased industrial traffic in the small municipality of Springfield in Elgin County. This photo, taken around 1900, shows a Sunday School picnic group on their way to Port Stanley.1

Then and Now Photos

Office of Dr. Peter W. McLay

Aylmer-Malahide Museum & Archives

1878

This rather stately home was once both the home and practice of one of Aylmer's earliest doctors, Peter W. McLay. Dr. McLay began to practice in 1870, starting a family practice that persisted for several generations. Though he died in 1907, he was survived by his son, Homer, who had followed in his footsteps and joined the medical practice. In 1934, Homer's nephew, Homer McLay Miller, also became a doctor, carrying forward the McLay medical tradition in Aylmer.

Molsons Bank

Aylmer-Malahide Museum & Archives

1897

This photo features one of Aylmer's early banks, the Molson's Bank, founded in 1853 by the same family that established Canada's Molson Brewery. From its headquarters in Montreal, the bank grew to over 125 branches across the country, until 1925, when it merged with the Bank of Montreal. The Aylmer branch building has been well preserved and is today home to Gloin, Hall & Shields Barristers and Solicitors.

Sovereign Bank of Canada

Aylmer-Malahide Museum & Archives

1897

This building started out as the private banking office of William Warnock. In 1904 it was registered as a branch of the Sovereign Bank of Canada, though that bank would collapse in 1908 during a financial crisis.

Thayer's Garage

Aylmer-Malahide Museum & Archives

1920

This was Thayer's Garage, a service station owned and operated by J. L. Thayer. In 1920, Thayer advertised gas at $0.27 per gallon, plus an additional $0.03 for tax. That's equivalent to $0.08 a litre. That might sound absurdly cheap to us today, but when inflation is taken into account it actually amounts to $0.99 a litre in today's money, a price not so far from what we might be familiar with.

The Sheppard's Coffee Story

Aylmer-Malahide Museum & Archives

1930s

Established in 1936 by Ray Sheppard, Sheppard’s Coffee Shop quickly became a local favourite. The shop hosted the first Royal Canadian Air Force members in Aylmer while their base was under construction during World War II. Ray would give children free ice cream during their last week of school, engendering many fond memories amongst those who grew up in Aylmer in those years. The shop closed permanently in 1965.

The Cenotaph

Aylmer-Malahide Museum & Archives

1930s

The Cenotaph, just to the left of the Post Office (now the Town Hall), commemorates the 55 men from Aylmer and Malahide who fell in battle during the First World War. The unveiling and dedication of the monument were originally intended to take place on Nov. 11, 1928, but were delayed until November 25th for an unknown reason. Over 2,000 people gathered to mark the occasion.

Years later the cenotaph would be amended to commemorate local men who fell in the Second World War and the Korean War.

Steam Laundry and the Old Town Hall

Aylmer-Malahide Museum & Archives

1939

The building at left was erected in 1874 and served not only as town hall, but also as a mechanics institute, police station, and opera house. The building was restored in 1982 and currently houses the theatre and library.

The Aylmer Inn

Aylmer-Malahide Museum & Archives

1933

"The three-storey brick building you can see at the far side of the intersection across the street (today the IDA Pharmacy) was the Aylmer Inn. Previously it had been known as the Brown House.

The building was gutted by fire only a year after this photo was taken. The fire was started by a 16-year-old boy, Walter Vaughan, and tragically took the lives of Grace Weatherall and her two daughters, aged 8 and 11, as they slept. "

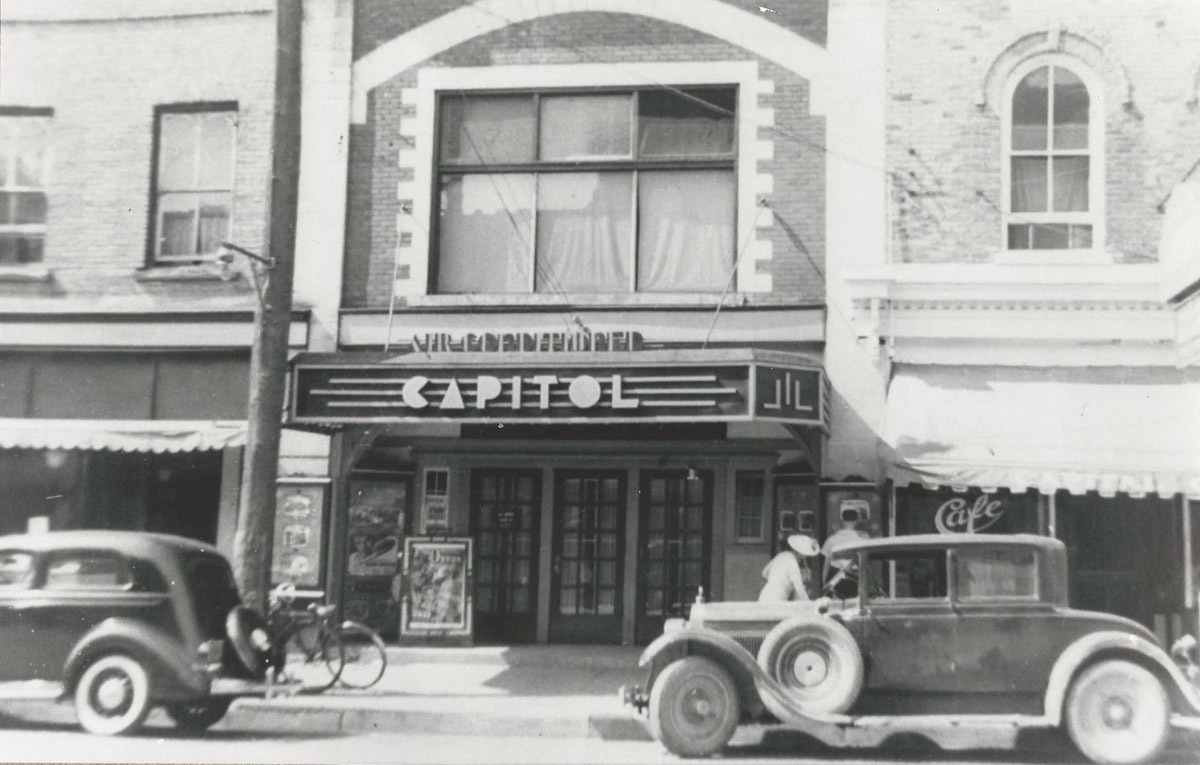

The Capitol Theatre

Aylmer-Malahide Museum & Archives

1939

Typical for the time, the Capitol, one of Aylmer's early theatres, had an air of grandeur inherited from the glitzy vaudeville theatres that were immensely popular before being run out of business by the movies. Going to a movie was an event that required smart dress. In those days tickets ran at about 40 cents--just over $7 today.

Durkee and Son

Aylmer-Malahide Museum & Archives

1950s

Durkee and Son has been a mainstay of clothes shopping in Aylmer since 1925. Unlike many other local outlets that have come and gone throughout the town's history, this store has persisted to the present--though now it's just known as Durkee's.

Getta’s Fruit Market

Aylmer-Malahide Museum & Archives

1950s

Pictured here is Getta's Fruit Market, located next to the longstanding Hills Pharmacy (which has itself changed faces many times throughout the 20th century). What began as Getta's Restaurant in the 1920s was later transformed into Peter's Fruit Market in 1948 by Peter and Stella Kapogines after their restaurant failed. The Fruit Market was more successful and stayed in business until 1983.