Walking Tour

Buried at Pleasant Valley

Remembering the Victims of Internment

Lindy Marks

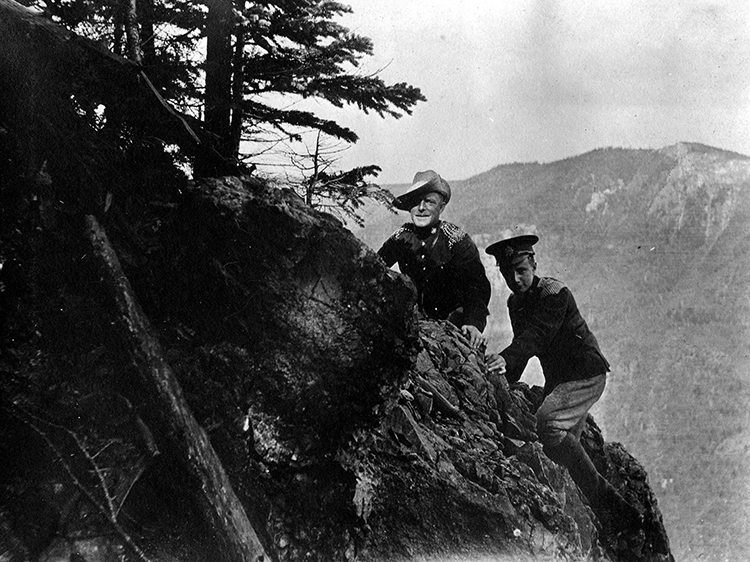

The Vernon internment camp opened on September 18, 1914 and remained in continuous operation until February 20, 1920, even though the armistice had been signed in November 1918. Eleven men died in the Vernon Camp and all were originally buried here in this quiet corner of the Pleasant Valley Cemetery.

Seven men remain interred in this cemetery, all of whom were from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The four Germans who were buried here were reinterred at the Woodland Cemetery in Kitchener, Ontario by the German War Graves Commission in the early 1970s.

Thanks to the efforts of the Vernon & District Family History Society, the stories of these men have been exhaustively pieced together from immigration documents, censuses, and government paperwork. The group, with help from the Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund, also erected new headstones at their graves to protect their memory.

On this tour, we'll visit the graves of Mile Hećimović, Ivan Jugo, Timoti Korejczuk, Stipan Šapina, Wasyl Shapka, Jure Vukorepa, and Samuel Vulović. We'll learn more about the lives they lead before the war, their hopes and dreams when they came to Canada, and the tragic circumstances of how they came to be laid to rest in this cemetery.

Special thanks to Lawrna Myers, whose Internee Research Report created for the Vernon Internee Headstones & Monument Project provided a wealth of biographical information about these men.

Itinéraire

Ce circuit se déroule dans l'enceinte du cimetière de Pleasant Valley, qui surplombe la ville de Vernon. Le cimetière est ouvert au public de 8h à la tombée de la nuit du 15 mars au 15 octobre. Du 16 octobre au 14 mars, le cimetière est ouvert de 8h à 16h.

Les tombes des internés sont situées à l'angle nord-ouest du cimetière. Pour accéder à cette partie du cimetière, entrez par la porte principale sur Pleasant Valley Road. Tournez à droite sur Elm Street et continuez jusqu'au bout de la route. Tournez à gauche et continuez jusqu'à l'angle arrière du cimetière. Là, sur la gauche, vous trouverez les tombes des internés.

Route

This tour is set in the grounds of the Pleasant Valley Cemetery overlooking Vernon. The cemetery is open to the public from 8am to dusk from March 15 to October 15. From October 16 to March 14 the cemetery is open from 8am to 4pm.

The graves of the internees are located at the northwest corner of the cemetery. To access this part of the cemetery, enter through the main gate on Pleasant Valley Road. Turn right on Elm Street and continue to the end of the road, turning left again and proceeding until you reach the rear corner of the cemetery. There on the left you will find the graves of the internees.

This project has been made possible by a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

1. The German Dead

Four German men died in the Vernon internment camp, but their remains were moved by the German War Graves Commission to the Woodland Cemetery in Kitchener, Ontario in the early 1970's. These men are Bernard Heiny, Karl Johann Keck, Leo Mueller, and Wilhelm Heinrich Eduard Wolter.

* * *

2. Ivan Jugo

Jugo was born in Fiume, part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in 1887. Today Fiume is known as Rijeka, the third-largest city in present-day Croatia, though the Italian and Hungarian name for the city is still Fiume. Historically, due to its strategic position and deep-water port, control of the city has been fiercely contested by Italy, Austria-Hungary, and Croatia.

* * *

Rijeka has been described as a "melting pot" of different cultures.2 Beginning in the 1880s, however, the Hungarian government began instituting more nationalistic policies and cut down the autonomy that the town had.3 Law in the Austro-Hungarian empire stipulated that any citizen had the right to education at the primary and secondary level in their first language but the number of schools teaching in languages other than Hungarian shrunk from this time on. Rijeka's Croatian language grammar school left the town in 1896.4

This move towards increasing Hungarian control of a town that had once been relatively autonomous and where Hungarians made up only 13% of the population by 1910, combined with a lack of land and high rents may have played a role in Jugo's decision to move to North America.5

Jugo arrived at Ellis Island, New York on April 6, 1912, aboard the ship Atlanta. He also used the name John Jugo. His family includes his mother, Rozalija Jugo, and two brothers, Frank and Virgo Jugo whose addresses were listed as Mihotići Post Office in what was then Francici, Austria. Today, Mihotići is a settlement of Matulji, Croatia.

Jugo may have been interned in Nanaimo, British Columbia before being moved to the Vernon camp. He was admitted to the Vernon Jubilee Hospital on September 6, 1916, with tuberculosis of the intestines. He spent six months in the hospital before dying of heart failure caused by tuberculosis on March 12, 1917.6

3. Jure Vukorepa

Vukorepa was born in Austria in 1886 or 1887. His name is also listed as George Vukop. The War Graves Registry indicates that his father lived in Šibenik, Dalmatia, Austria which is now part of Croatia. Šibenik is now the third-largest city in the Dalmatian region.

* * *

4. Mile Hećimović

Hećimović was born around 1885 in the village of Bukovac Perušićki in the municipality of Perušić in present-day Croatia. Jela and Anna, Hećimović's sisters, still lived in the village at the time of his internment and death. Hećimović also used the name Mike Lachin or Mike Lachen.

* * *

Immigration records show that Hećimović most likely left Europe for the United States aboard the Chemnitz. He arrived in Baltimore, Maryland in August 1909 and crossed the border into Canada five years later, in 1914. His destination was listed as Port Alberni, British Columbia and his place of origin was listed as Goldfield, Nevada.

Hećimović was first interned in Nanaimo, British Columbia before being sent on to Vernon. Like Hećimović, many of the men interned in the Nanaimo camp were miners who were arrested by the provincial police to appease the British and Canadian-born miners who refused to work with 'foreigners,' especially in a time of economic downturn. In 1915, the acting premier of the province, William Bowser, obtained permission from the federal government to arrest and intern Ukrainian miners working in Nanaimo, Ladysmith, South Wellington, and Cumberland.

Hećimović was admitted to the Vernon Jubilee Hospital on February 8, 1917. He died nine days later on February 17, 1917, from heart failure caused by tuberculosis.1

5. Samuel Vulović

Vulović was born in Austria in either April or September 1880. His father is Nickolas Vulovich born in Bocca di Cattaro, Austria and his mother is Godana Martinovich born in Braich, Austria. Vulović's immigration record, in the name Savo Vulovic, indicates he was Dalmatian. His Declaration of Intention to become a United States citizen indicates that he travelled to the United States from Cattaro, Austria. Bocca di Cattaro is the Italian name for the Bay of Kotor (also known simply the Boka) and the surrounding region which is in present-day Montenegro. Cattaro is now the city of Kotor, Montenegro, a town in a secluded area of the Boka.

* * *

Before moving to British Columbia, Vulović lived in Douglas, Alaska, and Dawson City, Yukon. The 1911 Canadian census records Vulović as being incarcerated at the New Westminster Penitentiary where he ultimately spent 11 years.

Vulović died at the Vernon Internment Camp on December 2, 1918 of a haemorrhage from a gastric ulcer, only two months after being interned.1

6. Stipan Šapina

Šapina was born about 1894 in Zupanjac, Bosnia. This information was provided by his brother, Nick Šapina who was also interned at the Vernon Internment Camp at the time of his brother's death. Currently, there are three settlements known as Zupanjac: one in Bosnia and Herzegovina, one in Croatia, and one in Serbia. An immigration record for his brother Nick lists Nick as immigrating from Zupanjac and records his nationality as Croatian.

* * *

Under a doctor's care from February of 1916, Šapina died of heart failure caused by tubercular meningitis on May 21, 1917. He was in his early twenties when he died.

The original marker for Šapina's grave was destroyed; the part that remained read: "Erected by ___k Sapina." This most likely referred to Šapina's brother, Nick. The remnants of the marker were removed and the base of it was used as the foundation for the commemorative monument that you see here.1

7. Timoti Korejczuk

Korejczuk was born on August 19, 1879, most likely in Kitsman, a city in modern-day Ukraine. Kitsman is in the historic region of Bukovina which was once a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. During the time that Korejczuk lived there, it was called Kotzman which is the German name for the city. Today, the northern half of Bukovina is part of Ukraine while the southern half is part of Romania.

* * *

Poverty, chronic lung disease, and the repression he faced as an activist led Korejczuk to immigrate to Canada in 1913 and quickly joined the growing USDP branch in Canada. Beginning in October 1914, Korejczuk was the western organiser of the party. In this role, he travelled through British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan speaking to crowds in the hundreds, advocating for better conditions for the immigrant working class.

Korejczuk continued in this role until 1918 when poor ill health forced him to settle in Vegreville, Alberta. He was arrested on September 5th, 1919, and sent to the Vernon internment camp.

Korejczuk died just ten days after his arrest. His official cause of death is listed as syncope, the medical term for fainting. Combined with his chronic lung problems, it is likely that fainting caused a sudden heart attack.

His death certificate lists his occupation as bookkeeper and the War Graves Registry names his mother as Paraska Korejczuk who was living in Kitsman at the time of her son's death.2

8. Wasyl Shapka

Shapka was born on February 23, 1892. Like Timoti Korejczuk, Shapka was born in the city of Kitsman, Ukraine, which was part of Austria at the time of his birth. His father is Hryhor Shapka.

* * *

A victim of the 1918 influenza epidemic that swept the globe, Shapka died from double pneumonia on December 10, 1918.1

Donate Now

If you enjoyed this free content, we ask you to consider making a donation to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, which is providing urgently needed humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian people are heroically defending their homeland against a genocidal war of Russian aggression. The humanitarian situation is critical and the needs immense. 100% of all donations made through this link go directly to supporting the people of Ukraine. Recently funded initiatives by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation include demining and removal of unexploded ordnance, and the evacuation of thousands of deaf people from the warzone.

Endnotes

1. The German Dead

1. Myers, 38.

2. Ivan Jugo

1. Ilona Fried, "'Out to Sea, Hungarians!' History, Myth, Memories: Fiume 1868–1945, Spiegelungen. Zeitschrift für deutsche Kultur und Geschichte Südosteuropas 15, no. 1 (2020): 100-101.

2. Fried, "Out to Sea, Hungarians!" 101.

3. Fried, "Out to Sea, Hungarians!" 103.

4. Fried, "Out to Sea, Hungarians!" 105.

5. Fried, "Out to Sea, Hungarians!" 101.

6. Myers, 18.

3. Jure Vukorepa

1. Myers, 61.

4. Mile Hećimović

1. Lawrna Myers, "Vernon Internee Headstones & Monument Project: Internee Research Report." Vernon & District Family History Society. (Vernon: 2015), 2.

5. Samuel Vulović

1. Myers, 68.

6. Stipan Šapina

1. Myers, 47.

7. Timoti Korejczuk

1. Dictionary of Canadian Biography, s.v. "Koreichuk, Tymofei," by Orest T. Martynowych, accessed September 16, 2021, online.

2. Myers, 31.

8. Wasyl Shapka

1. Myers, 53.

Bibliography

Myers, Lawrna. "Vernon Internee Headstones & Monument Project: Internee Research Report." Vernon & District Family History Society. Vernon, 2015.

Dictionary of Canadian Biography, s.v. "Koreichuk, Tymofei," by Orest T. Martynowych, accessed September 16, 2021. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/koreichuk_tymofei_14E.html

Fried, Ilona. "'Out to Sea, Hungarians!' History, Myth, Memories: Fiume 1868–1945. Spiegelungen. Zeitschrift für deutsche Kultur und Geschichte Südosteuropas 15, no. 1 (2020): 99-109.