Walking Tour

Life of the Doukhobors

The Epic Journey from Russia to Ootischenia

Carla Krempien

This tour will introduce you to the fascinating history of the Doukhobor people. We will start with their origins in 18th century Russia, where they were persecuted by the Czar for their religious beliefs which denounced religious icons and emphasized peace and equality. Eventually, in the 1890s, they fled Russia to come to Canada in search of religious and political freedom.

The Doukhobors who settled in British Columbia were immensely hardworking, setting up a number of successful industries, including a prosperous jam factory, while also living in communal village settlements. They were steadfast in their beliefs of equality and pacifism and wanted to live in accordance with their religious principles with minimal government intervention. When they immigrated to Canada, they brought their rich cultural traditions with them, including their rich choral singing tradition, which has grown out of the oral transmission of their prayers and psalms.

Not long after their arrival, Doukhobors came under immense pressure to assimilate into wider Canadian society from the Canadian government and news media sources. While Doukhobors in British Columbia no longer live in communal village settlements, their culture and traditions have survived despite intensive assimilation pressure.

This tour covers the former townsite of Brilliant, beginning at the scenic Brilliant Suspension Bridge, which was built by Doukhobors, and continues across the river to see where the famous jam factory once stood, along with the many other buildings that once made up the community here.

This project is a partnership with the Doukhobor Discovery Centre.

1. Brilliant Suspension Bridge

ca. 1920s

This is the Brilliant Suspension Bridge, constructed by communal labour in 1913. Steeped in history, this bridge symbolizes the industry and fortitude of the Doukhobors in their efforts to build a utopian society in the Columbia Valley. One of the few Doukhobor heritage sites still standing in the valley, the bridge was restored and declared a National Historic Site in the 1990s.

The bridge also brings into focus the epic landscapes of the area that surrounds you: the mighty rivers and the towering mountains that have dominated the human experience of this land for millennia.

* * *

Father de Smet, an early European visitor to the area, described how a particular Sinixt practice gave the Arrow Lakes their name.

"We passed under a perpendicular rock, where we beheld an innumerable number of arrows sticking out of the fissures. The Indians… have a custom of lodging an arrow into these crevices. This is the reason why the first voyageurs called these lakes, the Arrow Lakes."1

The fish and game were abundant in the waters and forests, and the unique geography allowed the Sinixt to flourish for millennia. They seem to have lived largely peaceful lives in the Columbia Valley, though there appears to have been one "great war" with the Lower Kootenay people over control of fishing grounds.2

During summer, the Sinixt would gather with other tribes at the base of Kettle Falls (in what is now Washington State), where basket nets scooped up the fish that tumbled down the falls. The catch, often salmon or trout, would be evenly distributed between nations.

A steady trickle of European explorers, fur traders, and missionaries began to filter into the area after first contact in 1811. They were looking to exploit the rich bounty of the Kootenays. The Northwest Trading Company (NWTC) relied heavily on Indigenous hunters and trappers for furs, and considered the Sinixt the best.

As the 19th Century wore on, the fur trade declined and the traders were replaced with miners, who coveted the rich mineral deposits in these mountains. Unlike the fur traders, they saw the Sinixt as hindrances rather than trading partners. In very short order, the Sinixt were evicted from their hunting and fishing grounds. The land that had been their home for millennia became host instead to transient miners and towns that were abandoned almost as soon as they were built. Decades later, this would also become the new home for many Doukhobor people.

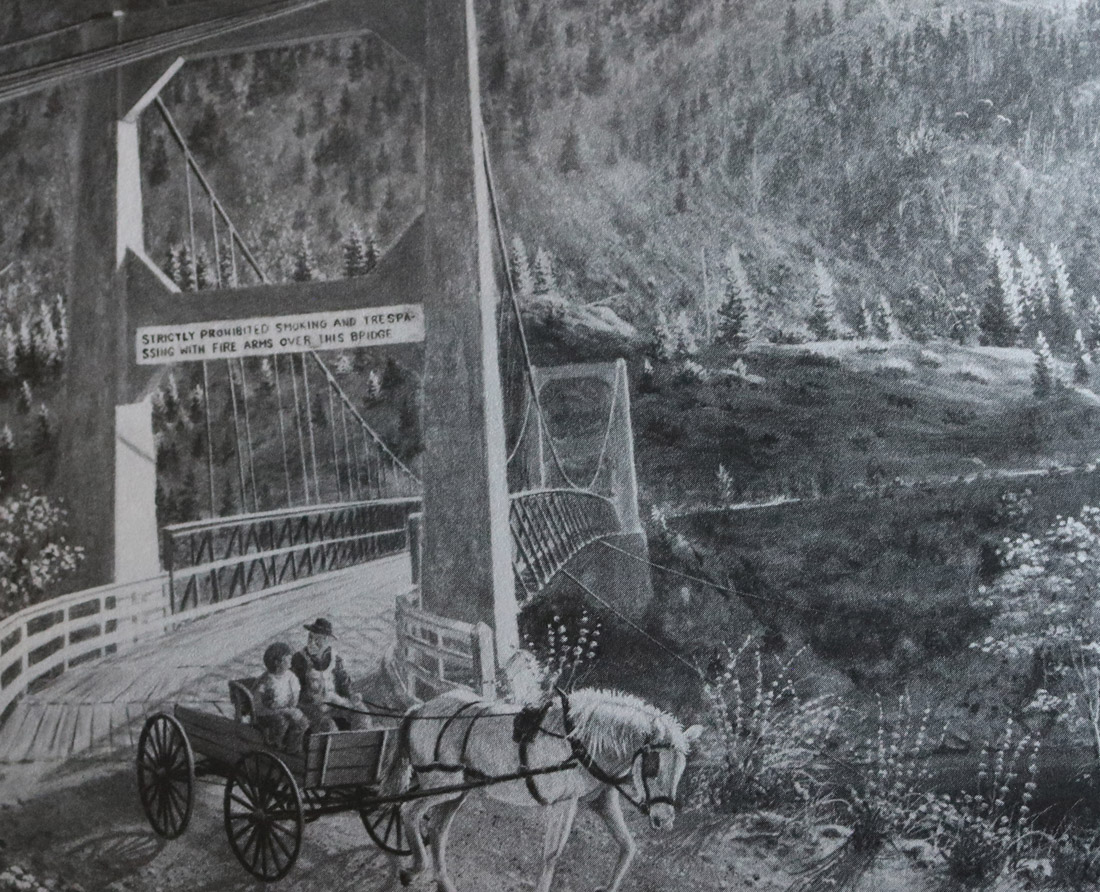

2. The Doukhobors

ca. 1910s

This drawing depicts a man and boy crossing the Brilliant Suspension Bridge in their horse-drawn wagon. The sign above the bridge reads, "Strictly prohibited smoking and trespassing with firearms over this bridge." The inscription is evidence of the pacifist ideology of the Doukhobors, a Christian religious sect that fled persecution by the Russian Czar and settled in this valley in 1911.

They commonly summarized their worldview with a saying: "The 'we' principle is everywhere, the 'I' is nowhere."1

* * *

One archbishop sneeringly named them the Dukhoborets, or "Spirit Wrestlers", meaning that they wrestled against the spirit of Christ. This was a moniker given to them with contempt, but the group relished and embraced the name, and so became Doukhobors.

Believing that the Spirit of God resides within every living being, the Doukhobors were pacifists who felt that all people were equal. Ultimately, they wanted to live a peaceful and communal life unmolested by the government.

In those early days, one of their first leaders, Illarian Pobirokhin, "proclaimed himself as 'Christ,' claiming that his divinity had been passed down to him since Apostolic times."2 During the reign of Catherine the Great, he gained a collection of "apostles" and established a small commune that achieved much of the religion's utopian ideals.

Pobirokhin began travelling and proselytizing, gaining adherents across an astonishingly vast geographic area, from Ukraine in the west to Siberia in the east and from Finland in the north to the Caucasus Mountains in the south.

His teachings posed a direct challenge to the two dominant institutions in Russian society: the church and the state. The refusal of the Doukhobors to adhere to the rigid orthodoxy of the Russian Orthodox Church undermined the immense power of the clergy and challenged the religiosity of the Czar. Their pacificism threatened to sap the Czar's army of its strength.

It's not hard to imagine how the Czar responded to this threat.

"The authorities treated them with the greatest severity for they saw in the Doukhobors' teachings the seeds of future revolution in society."3

The Doukhobors were often treated cruelly by Russian rulers and were forcibly exiled to harsher and harsher climates on numerous occasions, in addition to being whipped and mutilated.

One historian described the trauma these deportations had on peasants who had farmed the same plots for generations:

"On parting from the land, which for so many years had fed them, the Doukhobortsi women kneeled and pressed her to their breasts; they kissed her, and, sobbing, stretched their hands to heaven and sang mournful songs."4

Nevertheless, the Doukhobors showed their resilience by adapting to each new environment, often flourishing despite the heavy odds stacked against them. Their genial nature won them friends amongst the peoples of the steppe, who often helped them survive.

“The wild tribes were favourably impressed by their non-resistant neighbours (the Doukhobors), who, when molested, neither retailiated nor sought police protection…”5

However, not even their fortitude could preserve them from the continued persecutions, famines, and harsh climates.

By the end of the 1800s, life had become intolerable, and the Doukhobor leader Peter Verigin wrote:

"The best way of dealing with us would be to let us settle in one place where we could live and labour in peace."6

It was time to find their promised land where they could live in accordance with their religious principles without persecution.

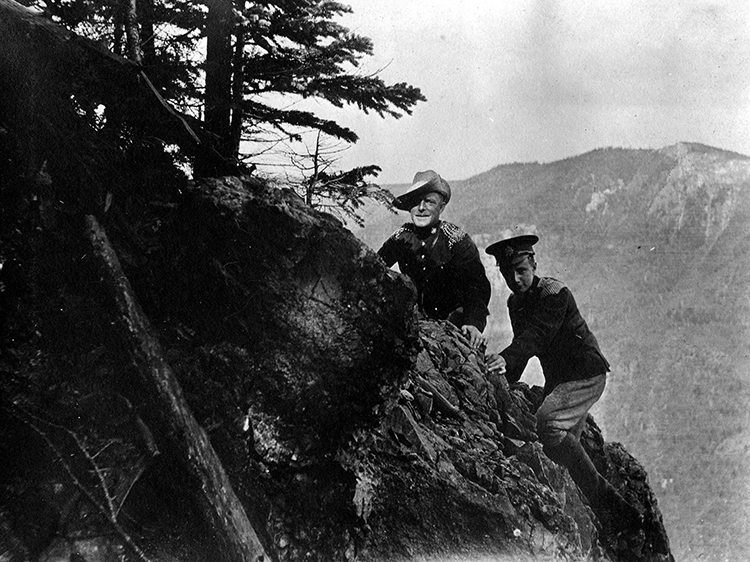

3. Search for a Promised Land

ca. 1910s

While the Brilliant Suspension Bridge is one of the last obvious traces of the early Doukhobor settlement here, these valleys were once dotted with dozens of Doukhobor communal villages, which consisted of large two-storey houses, known as doms, as well as U-shaped annexes.

In the 1890s, the famed Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy was an ardent supporter of the Doukhobor cause and aided their leader Peter Verigin in his mission to find a new home for his people beyond the reach of the Czar.

* * *

The Canadian government, for its part, was keen to find more settlers for the sparsely populated west, and thought the Doukhobors would be industrious and resilient.

The escape from Russia didn't come a moment too soon: by the time the Doukhobors began immigrating to Canada in 1899, almost a quarter of their community had died as a direct result of persecution.

The search for a new home wasn't an easy one. After a failed attempt by the Doukhobors at creating a colony in Cyprus, protracted negotiations between Doukhobor representatives and the Canadian government began. Doukhobors would have to overcome the racism that prevailed in the upper crust of Anglo-Canadian society at the time. Many believed in a fine-grained hierarchy of races, even amongst European nations, which placed Eastern Europeans below people from Western Europe.

One politician derisively said of the Doukhobors:

"We want all the German and Scandivian immigration we can get, for these people are of our blood, but the introduction of another strain cannot be regarded as a successful means of populating the northwest."1

Advocates for the Doukhobors in Canada argued that another religious group, who had also emigrated from Russia to live in accordance with their religious beliefs and values, had succeeded in the Canadian northwest.

The Mennonites had settled in Canada a few years before, and they'd proven to be industrious and resilient farmers. Peasant life on the harsh Russian steppes proved to be excellent preparation for pioneer life on the prairies.

The Doukhobors were granted permission to settle in Canada. Furthermore, they were promised that they would not be forced to fight in any wars, would be given full religious freedom, and would be given land. Additionally, they were told they would not be required to pledge allegiance to the crown, a promise that would soon prove empty.

In January 1899, over 2,000 Doukhobors landed at Halifax after an arduous 8,000 kilometre journey by steamship. Roughly 7,500 Doukhobors would ultimately emigrate to Canada. The Canadians were stunned to see this strange group dressed in Russian garb on a ship so clean it appeared as if it was about to depart on its maiden voyage rather than complete a storm-tossed month at sea.

The ship's captain expressed a sentiment that would become common to those who encountered the Doukhobors: "You can hardly believe it, but I am honestly sorry to see them leave the ship. I do not know when I have been so interested in any class of people as in these Doukhobors."2

When the Chief Health Officer at the port of Halifax approached the ship to inspect it, he was stunned by what he heard:

"Across the water comes the hum of human voices raised in song. Two thousand and seventy-three Doukhobors are chanting a psalm. Hilkoff translates for us: "God is with us, he has brought us through."3

As he boarded the ship:

"...the entire multitude, in an astonishing gesture, fling themselves to their knees and press their foreheads to the deck… They are not bowing to the welcoming committee but to "the spirit of God in their hearts, which has made them take us as brothers in their own homeland of Canada."4

These people were not like any group of immigrants who had come to Canada before.

After quarantine, the group continued on to Saint John, New Brunswick, and from there took the train to Saskatchewan, their promised land.

The Doukhobors quickly established their community without wasting a moment. They would build their houses while clearing and planting their fields. Every person participated - they had to adapt to life in a new land, after all. Outsiders noticed how “the women were hitched to plows like horses.”

Soon, they had developed several self-sustaining communities across the prairie. However, they soon came to learn that the independence they came here for wasn’t as easy to get as they hoped.

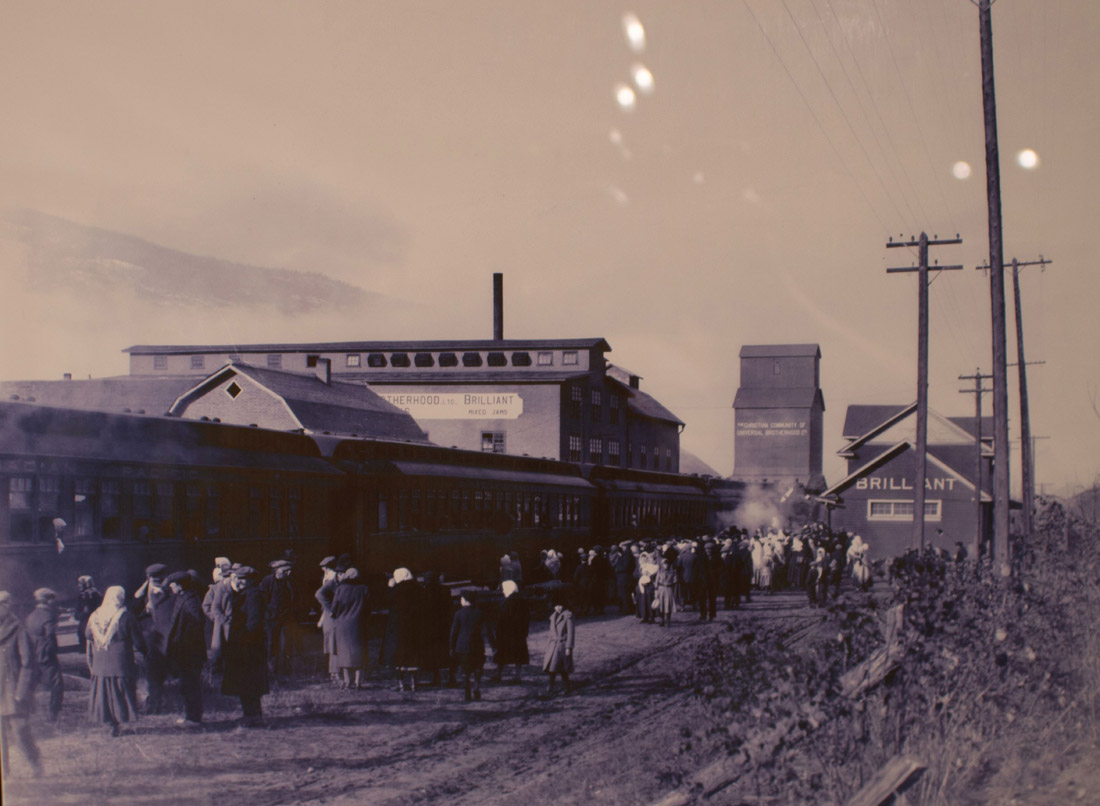

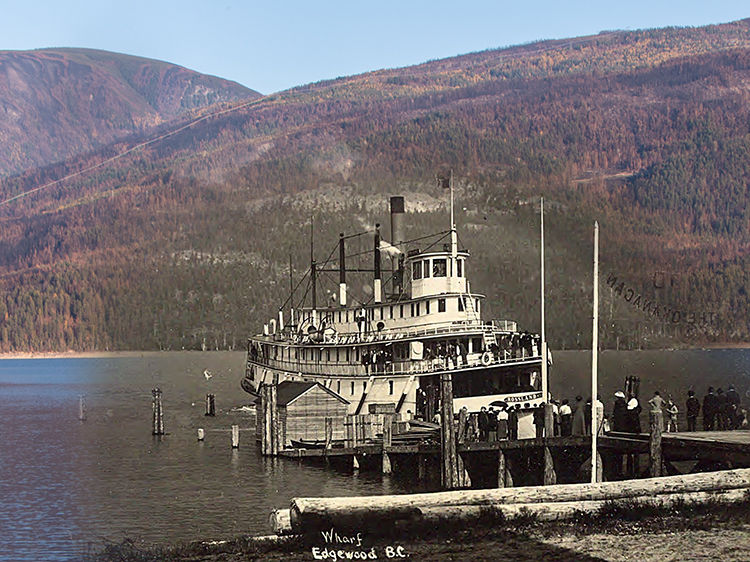

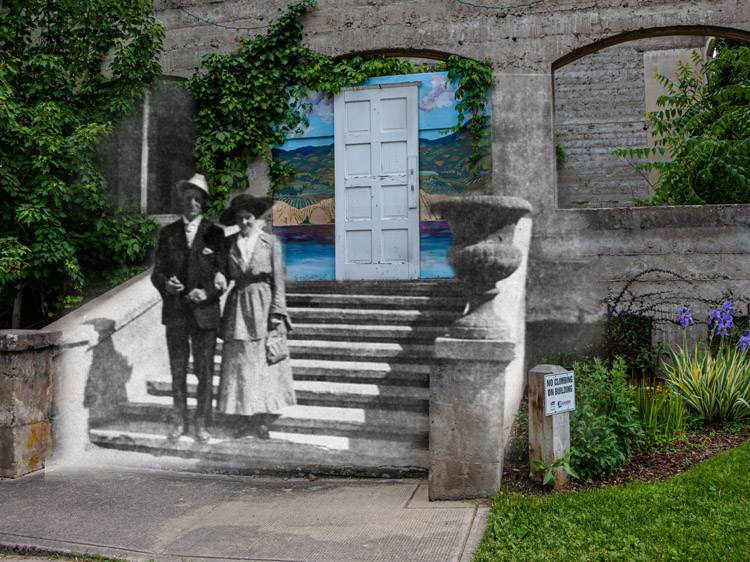

4. The Journey's Last Leg

ca. 1910s

This was once the site of the Brilliant Train Station, the heart of the Doukhobor community that was founded here in 1908.

As more Doukhobors settled on the prairies after 1899, they found themselves increasingly alienated and distrusted by the other settlers. Their "otherness" irked the communities around them, and their industriousness, which led to profit, annoyed their neighbours.

The Canadian government reneged its promise to the Doukhobors and demanded that they swear the oath of allegiance to the British Crown and sign for their homesteads independently. While some Doukhobors compromised with the government, many refused, and their land was taken from them. It seemed that Canada might not be the saviour they had hoped for after all.

* * *

When Verigin first visited this valley he was smitten. He found the air "healthful like Switzerland."1 The land itself, covered as it was at the time in thick snow, reminded him of his home in Siberia. He knew the soil would be perfect for seeding and that the climate (despite the snow) was much milder than that of Saskatchewan.

"As for the forest, it is our friend; we will use it to build our homes. It’s splendid timber, the soil will need irrigation, but there is water everywhere- cheap, clear and clean. No schools. No government interference. An ideal place to build the brotherhood."2

He purchased the land on the spot and named the area 'Dolina Ooteshenie', meaning 'Valley of Consolation.' The settlement itself would be called 'Brilliant,' after the sparkling quality of the rivers.

Then, like a true Doukhobor, he got to work.

In the spring of 1908, 85 men arrived in Brilliant and began the arduous task of clearing the land, primarily using handheld tools. They quickly erected a sawmill and set up a shelter in an abandoned mine while they constructed their homes.

Soon, the women and children joined them and lost no time planting vegetable gardens and fruit trees. These trees contributed a vital source of shared income to the community, as they processed the fruit into delicious handmade jam.

Everything the community needed, they built together: roads, ferries, and bridges—the most notable being the Brilliant Suspension Bridge. They dug two extensive irrigation systems, one of which was over 11 kilometres long.

By 1915, over 5,000 Doukhobors had settled on the land, and Brilliant prospered. There was a huge jam factory, a hospital, a dry goods store, and communal meeting centres.

In the beginning, the Doukhobors and their work habits were welcomed in the Kootenays.

Reverend John McDougall, for instance, stated, "I further found that [the Doukhobors] were both happy and healthy and very much appreciated by the General public of B.C. Railway men and merchants… spoke of them as peaceful and industrious and valuable people."3

5. The Sobranie

ca. 1920

A sobranie (traditional Doukhobor meeting) of young adults in Brilliant. After their arrival to British Columbia, some Doukhobor children attended the province's public schools when they were located near Doukhobor settlements. New schools and new school divisions were created to help accommodate nearby Doukhobor school children. In fact, the Brilliant School District, which contained an “all-Doukhobor” school board, opened its first school in 1912 and welcomed 48 children who attended school regularly.1

* * *

Doukhobors added additional objections to the province’s public school system providing further justification for the withdrawal of their children. In their own statement, released in 1912, Community Doukhobors asserted that, “The school education teaches and prepares the people, that is children, to military service, where shed harmless blood of the people altogether uselessly...We consider this a great sin.”3

The Doukhobors opposed sending their children to public school because they felt that the Canadian governments used schools to promote overt patriotism and nationalism as well as military discipline. Additionally, Doukhobors worried that the public school system was ripe for exploitation and that it would lead to the separation of their community.

Looking back, they might have been onto something—just two years later, the First World War began, in which tens of thousands of young Canadians enthusiastically rushed to recruiting centers to sign up, only to perish in the trenches.

For a time, Peter Verigin was able to start a Doukhobor “private school” and even hired a non-Doukhobor teacher for the school, but it did not function for long. In 1915, some Doukhobor children returned to the school in Brilliant as Peter Verigin and Attorney General Bowser came to an agreement which saw the removal of militaristic education in Doukhobor populated schools. More schools were built around Doukhobor settlements, but in the early 1920s Doukhobor school attendance started to decline.

Some academics have stated that the reason for this decline was the worsening relations between the Doukhobor community and the English-speaking public and particularly with returning soldiers from the First World War, who started calling for Doukhobor deportation.4 Stiff fines and penalties (including the seizure of community property) were levied against the Community members for not sending their children to school. Such governmental responses only deepened the divisions between the Community Doukhobors, the Sons of Freedom, and the provincial government.

6. Governing by Consensus

Anna P. Markova - Personal Collection

ca. 1920s

This photo shows a group of distinguished gentlemen from the Christian Community of Universal Brotherhood (CCUB). They held their meetings in Brilliant in front of the Kootenay-Columbia Preserving Works Jam Factory that once stood on this spot.

In Russia, the Doukhobors primarily followed the “mir” system of living as many lived within communal societies. Though there was usually a leader, all decisions were made in a democratic manner through large community meetings called sobranies. All members of the community shared resources and money, which were redistributed to ensure that everyone was taken care of equally.

This was not the communism of the Soviet Union and Marx, but an older kind of peasant communalism.

The Doukhobors in Canada attempted to replicate this way of life, and the CCUB was set up to enact the democratic will of the community and manage their finances.

* * *

Firstly, upon arrival in Saskatchewan, the community was widely dispersed across the prairies, making it difficult to share resources. Some Doukhobors who came to Canada had been less exposed to persecution and trauma in Russia and chose not to live within a communal setting once they moved to the prairies.Thirdly, the influx of “land hungry settlers” to the prairies from Ontario and the British Isles complained that the Doukhobors’ communal living arrangements contradicted Canadian ways of life and left too much land untilled and “unused.”1 This increased the pressure on the Canadian government to dissolve communal Doukhobor settlements.

Frank Oliver replaced Clifford Siftion as Minister of the Interior in 1905. Oliver opposed the exemptions given to the Doukhobors by Sifton which allowed them to live communally and did not require them to take the oath of allegiance. With an influx of settlers to Saskatchewan who were willing to become “British subjects” and farm independently, Oliver opted to rescind the previous exemptions that were granted to the Doukhobors. This crushed most of the Doukhobors’ communal settlements in Saskatchewan.

Some Doukhobors were willing to compromise with the government by signing for the land independently and by reluctantly completing the oath of allegiance. These became known as the Independent Doukhobors, while those who followed Peter Verigin and the communal lifestyle became known as the Community Doukhobors. When Verigin led his people to the Kootenays, a number of Independent Doukhobors chose to stay in Saskatchewan, where a large community remains to this day.

The Community Doukhobors who settled in Brilliant managed to maintain their communal lifestyle under the guidance of the CCUB. Each family was given an allowance for food and clothing as well as for basic necessities such as shelter. Members were allowed to take work outside of the community but had to pay a fee to the CCUB yearly.

A government official writing about the Doukhobors said:

"Witness after witness holding large areas of land declared that he regarded the Doukhobors as desirable neighbours because of the high-class cultivation of their lands and their peaceable, quiet natures."1

Though life did seem harmonious once again, Verigin worried about the loss of more Doukhobors and believed a stricter code of conduct was necessary. He excommunicated those who communicated with their former brothers and sisters, the Independent Doukhobors. While this seemed to work for a while, it wasn’t long before some community members began to step out of line.

7. Communal Living

ca. 1910s

This photo shows the dining hall that once stood on this spot. The Doukhobor practice of communal living went far beyond just the sharing of finances; they embraced it in almost every aspect of their lives.

The Doukhobors lived together in large communal houses, ate together in dining halls, and gathered together at sobranies. To be alone was a rare occurrence in the Doukhobor community.

In Brilliant, there were 74 community homes, called 'doms'. Each dom could house up to 30-50 people. Land was fairly limited, so living in these homes allowed the Doukhobors to consolidate their community, with each house given 100 acres of land.1

* * *

Everything was communal in these doms, including dining areas, brick ovens, and storage for produce and canned goods. The houses were kept exceptionally clean, and families took turns cooking for the home. Each community had a bania, a Swedish-style sauna that was sometimes attached to the doms, and the entire household—both men and women—bathed together every Saturday, using the sauna as a cleanser and health elixir.

The cleanliness of both home and body was seen as indicative of good moral character. As a common saying went, "Since the body is the abode of God, let us keep it clean in word, thought and deed."2

The Doukhobors often held spiritual ceremonies, called “moleniya”, which would take place in either a home or a meeting house. The men and women would sit on opposite sides of the room with bread, salt, and water on a table between them. They considered these items essential for life and all they needed to survive. The group would sing psalms in Russian that had been written centuries ago and share opinions on relevant issues of the moment.

After working together in the fields and factories, households would share a communal meal. In the evening, they would sit together on their porches, knitting, sewing, or carving, and sing beautiful acapella harmonies.

The Doukhobors lived a simple and idyllic communal life—a rarity in modern Canadian society—where every person was equal and needed. Despite his role as community leader, Verigin lived the same lifestyle as his community.

As one observer remarked, "[Verigin] scolds no one nor gets angry, and even eats with us from one bowl."3

8. The Power of Song

1929

"Life is worth living, while we are singing.

Here fortune and gladness continually flow.

Love never ending flows like a streamlet

and brotherly friendship blossoming grows."

- Doukhobor Folk Song1

In this picture, a choir group is gathered in front of the railway station that once stood on this spot. Choir groups who travelled among the Doukhobor settlements across Western Canada were a staple of life amongst the Community Doukhobors.

The Doukhobors were always singing. It was, and still is, a vital part of Doukhobor life. Through song, they demonstrated their passion, sadness, and joy. Stereotypes of the Doukhobors portray them as somber people, but this could not be further from the truth when it came to singing. The Doukhobors had no reservations about displaying emotion with their voices.

* * *

As pacifists, they would use song, not violence to show their dissent. During protests, they would often march and sing for hours or even days. Music brought the Doukhobors together, reminding them of their shared experience and shared cause.

Later on in the 20th century, Doukhobors in British Columbia and Saskatchewan formed choirs such as the one in the photo above. Often, they travelled to other Doukhobor communities across Canada, usually performing with an accompanying drama group. Doukhobor choirs have also performed at national events such as Expo '67 and Expo '86. The Doukhobors viewed the singing of psalms as an essential part of their history and culture, and they have worked hard to pass this tradition on to the next generation.

9. The Love of Drama

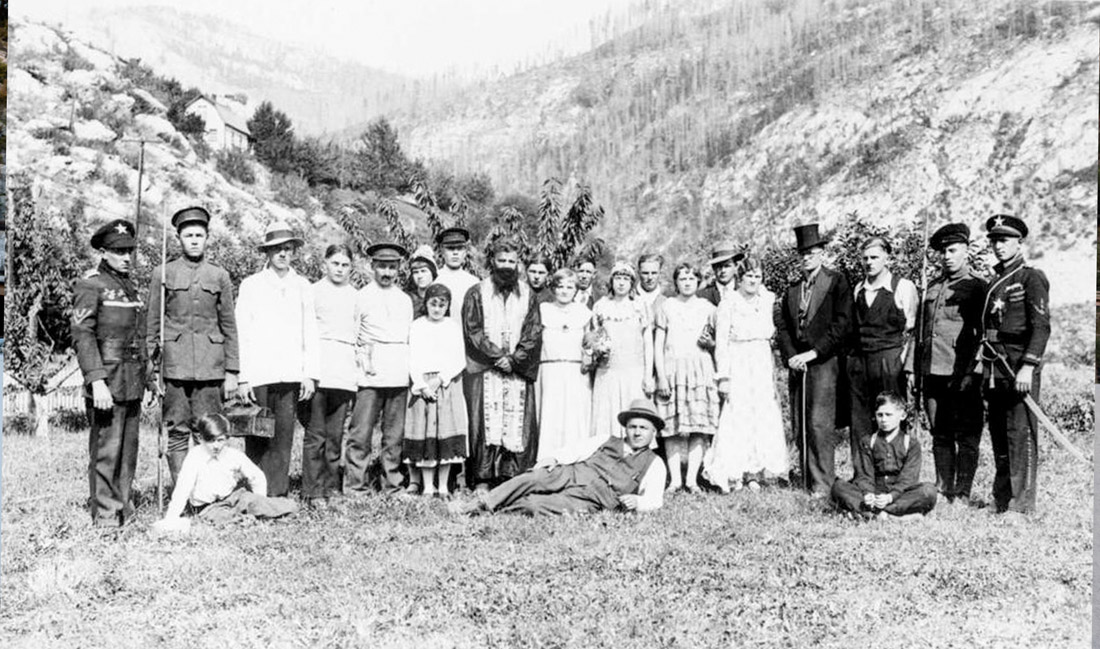

1931

This photo shows a travelling drama group that is ready to perform a reenactment of the Burning of the Arms, an identity defining event in the Doukhobors' history. The group contains both men and women, including some dressed as the Czar's soldiers, an Orthodox priest, and protesters dressed in white.

One of the most central Doukhobor beliefs is that the Spirit of God resides within every living being. This belief was promoted by the first known Doukhobor leader, Siluan Kolesnikov, who maintained that every living being carried “divine spark” within. This core tenet lends itself to the Doukhobors’ belief in both equality and pacifism.

* * *

This speed was also thanks to the equal participation of every member of the community in breaking ground, regardless of gender. Women were seen beside men doing the same back-breaking work, ploughing fields, clearing brush, and building homes.

An Anglo settler woman remarked:

"The neatness of the (women’s) work was astonishing, for when in some cases logs large enough to build a log house were to be found, in others they had to be woven out of coarse willow branches…"1

While men and women worked equally hard at labour and farm tasks, the community still organized some labour along gendered lines. Often, it was men who took jobs outside of the community, working on the railroad or mines, and women who cooked, served, milked the cows, and tended the gardens. It was the role of the matriarch to educate and care for the children.

Marriages were rarely arranged. Instead, the Doukhobors married for love and held surprisingly informal weddings—small gatherings that were not presided over by a priest or even recorded by state or church. Individual family members were cherished, but it was to the greater community that they gave their energy, passion and loyalty.

10. The Jam Factories

1940-1943

When the Doukhobors moved from the prairies to the Castlegar area, they found a land with rich soil and great opportunity.

Fruits and vegetables were the staples of the Doukhobor diet. The Community Doukhobors had lamented the lack of good planting soil for produce in Saskatchewan—land that is much more suitable for grain—and had struggled to produce enough of their desired foodstuffs.

In the mountain valleys of eastern British Columbia, they found fertile soils perfect for fruit orchards and vegetable gardens. They set to work immediately and quickly built a great business enterprise manufacturing jam and preserves.

* * *

The jam they produced was the high-quality K-C brand, made with fruit, pure cane sugar, and water. Brilliant's most famous jam recipe included twelve parts strawberries, fourteen parts sugar, and five parts water. It was immensely popular and became a top seller across North America.2

The First World War was an economic boon for the Doukhobors. As conscientious objectors, they did not lose any workers to the army.

This did not sit well with their Canadian neighbours, some of whom harboured suspicions of the Doukhobors for their apparently bizarre beliefs. The Doukhobors attempted to make amends by offering donations of wheat and jam to those who were struggling. However, outsiders continued to resent the community and their success in the midst of so much trauma.

11. Building Resentment

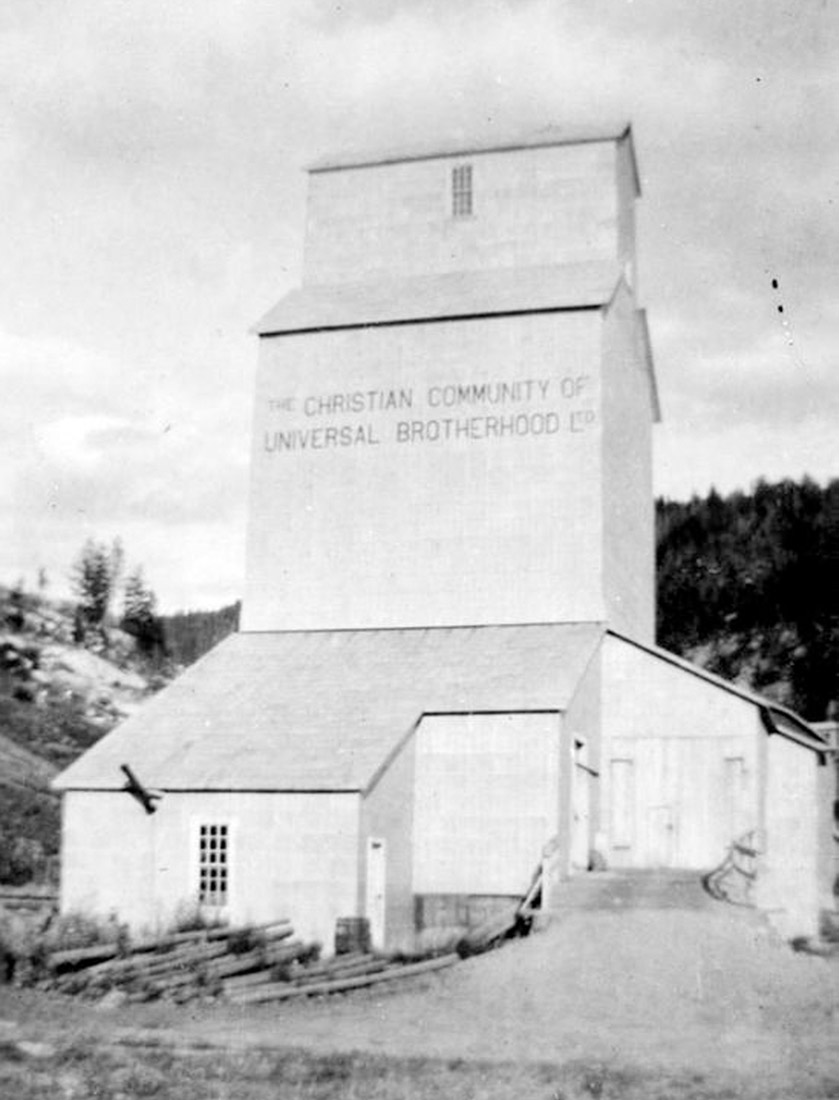

1930

Here stood the community grain elevator, owned and operated by the Christian Community of Universal Brotherhood. The Doukhobors grew grain and kept cattle for the community's use only; their fruit orchards, on the other hand, were the primary source of the community's revenue.

Though many people had been uncomfortable with the apparently strange practices of the Doukhobors ever since their arrival in Canada, their enviable financial success after coming to the Kootenays created a new cause for resentment. As the years wore on, the initially relatively tolerant attitudes of nearby Canadian settlers began to sour. After the First World War, these attitudes grew into outright attempts to criminalize the Doukhobors' beliefs and evict them from their lands.

* * *

A 1910 editorial in the Daily Province wrote of the Doukhobors:

"What we want is Canadian citizens, and the man who does not give promise of becoming within a reasonable time a Canadian citizen should not be admitted at all."1

This distrust was compounded by the emergence of a Doukhobor faction called the Sons of Freedom in 1903. Svobodnikii, as they were also known, interpreted Peter Verigin's teachings differently and argued that the Community Doukhobors were moving too far from God and closer to materialism. They lived on the fringes of the community, carrying out nude protests and burning down the homes and buildings of the Community Doukhobors.

The Sons of Freedom were condemned by the Community Doukhobors, who said, "anyone who participates in a violent act, ceases to be a Doukhobor."2

Unfortunately, this didn’t stop the national press from blaming all acts perpetrated by the Zealots on the Doukhobors as a whole.

One government document, written in response to these acts of arson, said:

"The sooner this commune be broken up, the sooner will be real progress amongst these simple misled people."

Despite this turmoil amongst the Doukhobors, the community continued to prosper. Unfortunately, this prosperity fueled further anger from the community's neighbours.

Before the Doukhobors arrived, there had been many dominant employers, first the fur trade, then mining and railway construction, which caused cycles of boom and bust, making life precarious for many settlers in the region.

The Doukhobors, on the other hand, created an entirely self-sufficient and sustainable industry through their agricultural prowess, along with brick-making and logging operations, and a very successful jam factory. The enormous buying power of the CCUB did not always sit well with their non-Doukhobor neighbours.

12. Death of Peter Verigin

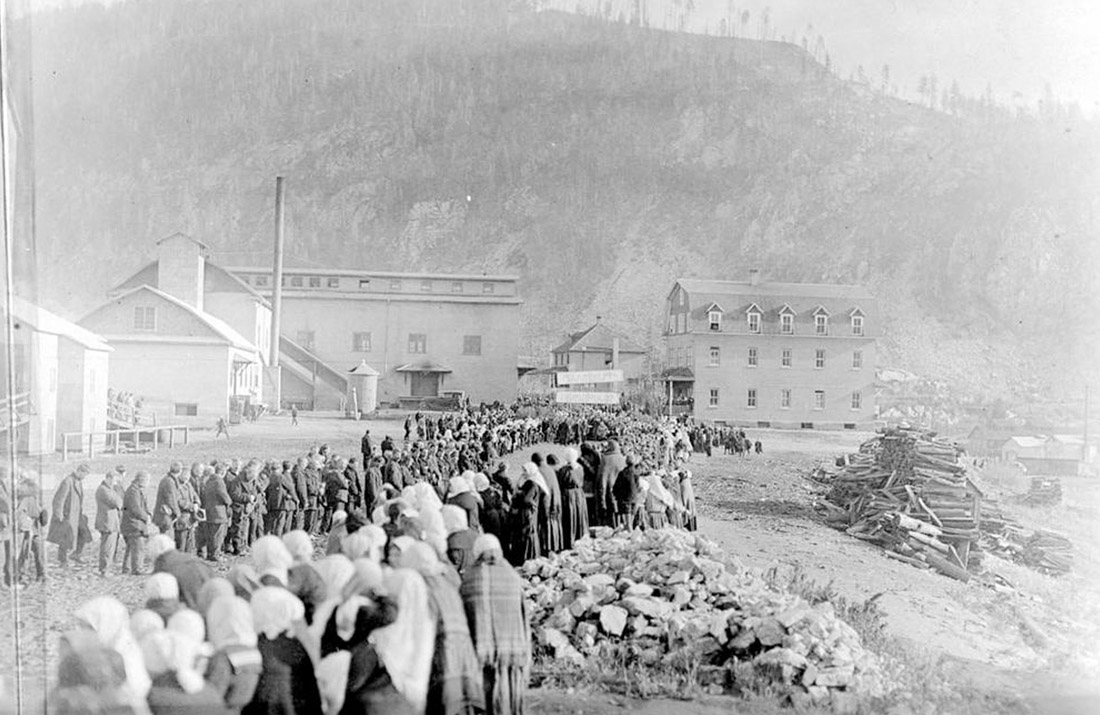

1924

In this picture, a crowd of thousands has gathered for Peter Verigin's funeral. His October 1924 death in a mysterious commuter train explosion on the Kettle Valley Train Line robbed the community of the one leader who was able to unite the Doukhobors and who could have led them through the challenging years ahead.

A huge crowd of over 7,000 people, including 500 non-Doukhobors who praised Verigin for his business acumen, showed up for the leader’s burial in a grand tomb just up the hill from this spot. It was probably the largest gathering of Doukhobors in Canadian history.1

* * *

Peter Petrovich’s tenure as Doukhobor leader was full of problems.3 Not only was Chistiakov dealing with his own health and legal problems over his leadership tenure, but the Sons of Freedom faction grew in numbers and the CCUB went bankrupt in 1938. Peter Petrovich’s mismanagement of community funds may have been a factor that contributed to the bankruptcy of the CCUB in 1938, along with the Great Depression and an extreme lack of government support. Peter Petrovich Verigin died in 1939.

The CCUB was succeeded by the Union of Spiritual Communities of Christ (USCC). John J. Verigin Sr., the grandson of Peter Petrovich Verigin, was named as Honorary Chairman of the USCC. As the Second World War emerged at the end of the 1930s and continued into the 1940s, Community Doukhobors were able to remain on CCUB land where they lived. After the war, however, they were posed with the difficult option of buying back land from the government and transitioning to private land ownership.4

The question of private land ownership was deeply problematic for the relations between the Community Doukhobors and the Sons of Freedom Doukhobors in British Columbia. Although there was minimal Sons of Freedom activity during the Second World War, they were blamed for burning down the profitable Jam Factory in Brilliant in 1943. Their arsonist activities increased throughout the 1950s, as British Columbia’s Social Credit government took a hardline approach when dealing with Sons of Freedom and as more Community Doukhobors were departing from the communal lifestyle.

Canada was modernizing and becoming more urbanized after the Second World War. Doukhobors continued to face immense assimilation pressure. While the communal lifestyle of many Doukhobors in Canada greatly diminished after the collapse of the CCUB, many Doukhobors continue to preserve their distinctive traditions and culture.

Today, almost 4,000 Canadians self-identify as Doukhobor, and though they may not have maintained all of the traditions of their forefathers, the history and passion of this incredible group of people lives on.

Endnotes

1. Brilliant Suspension Bridge

1. Karen w. Farrar, Castlegar: A Confluence, (Castlegar: Castlegar & District Historical Society, 2000), 37.

2. Farrar, 41.

2. The Doukhobors

1. Koozma J. Tarasoff, Plakun Trava: The Doukhobors, (Grand Forks: Mir Publication Society, 1982), 6.

2. Tarasoff, 3.

3. Tarasoff, 3.

4. Tarasoff, 10.

5. Tarasoff, 12.

6. Tarasoff, 30.

3. Search for a Promised Land

1. Tarasoff, 47.

2. Tarasoff, 44.

3. Pierre Berton, The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914, (Toronto: Anchor Canada, 2002), 158.

4. Berton, 158.

4. The Journey's Last Leg

1. Tarasoff, 102.

2. Tarasoff, 102.

3. Tarasoff, 104.

5. The Sobranie

1. Janzen; Lyons, 117-118.

2. Janzen.

3. Janzen.

4. Janzen.

6. Governing by Consensus

1. Tracie, 95.

2. Tarasoff, 118.

7. Communal Living

1. Tarasoff, 109.

2. Tarasoff, 109.

3. Tarasoff, 110.

8. The Power of Song

1. Farrar, 131.

9. The Love of Drama

1. Tarasoff, 57.

10. The Jam Factories

1. Farrer, 113.

2. Farrer, 116.

11. Building Resentment

1. Tarasoff, 117.

2. Tarasoff, 133.

3. Tarasoff, 126.

12. Death of Peter Verigin

1. Tarasoff, 140.

2. Androsoff, 166.

3.

4. Androsoff, 248-249.

Bibliography

Androsoff, Ashleigh Brienne. “Spirit Wrestling: Identity Conflict and the Canadian “Doukhobor Problem,” 1899-1999.” Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Thesis, University of Toronto, 2011.

Farrar, Karen w. Castlegar: A Confluence. Castlegar: Castlegar & District Historical Society, 2000.

Janzen, William. “Forced Doukhobor Schooling in British Columbia.” http://www.doukhobor.org/Forced-Schooling.html

Tarasoff, Koozma J. Plakun Trava: The Doukhobors. Grand Forks: Mir Publication Society, 1982.

Tracie, Carl J. Toil and Peaceful Life: Doukhobor Village Settlement in Saskatchewan 1899-1918. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina, 1996.

Berton, Pierre. The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914. Toronto: Anchor Canada, 2002.