Walking Tour

Strathmore at War

A World at War

Andrew Farris

Glenbow Museum and Archives NB-39-385

Safe as it is in the middle of the Canadian prairies, the scourge of war has never come to Strathmore. Yet during two world wars the people of Strathmore set aside their ploughs and flocked to the enlistment offices to fight in defence of the British Empire and democracy. It is indeed remarkable just how many of tiny Strathmore's men and women answered the call - and how many of them never returned.

In this tour we will look at Strathmore's experience in two world wars. We will ask why they chose to fight in a war thousands of kilometres away, and what happened to those who did. We will follow the touching story of Strathmore's Bert Berry, whose letters to his mother are preserved in the Glenbow Archives. Next we will trace the experience of Strathmore in the Second World War, when once again the people of Strathmore took up arms.

This project is only possible with the generous sponsorship and support of the Western District Historical Society. We also owe thanks to the Town of Strathmore, the Strathmore Travelodge, and members of the Western District Historical Society.

1. The Memorial Hall

1921

You're standing now in front of the Legion Hall, built in 1920 to commemorate Strathmore's fallen in the First World War. This photo shows a military band, a crowd of veterans, their families,and the people of Strathmore breaking ground for construction of the new hall. When war was declared in 1914, like towns and cities across Canada Strathmore erupted in celebration. Nobody could have imagined what was to come.

* * *

Some people were concerned about the cost in blood and treasure, but most agreed that whatever terrible new weapons were to be employed in the War to End All Wars, the dogged courage of the Empire’s volunteers would win out over the dastardly Huns, as the Germans became known. It was commonly believed the war would be over by Christmas.

To our modern eyes it all appears so heartbreakingly naive. In an article titled “Armageddon”, the Strathmore Standard’s August 5 edition read:

"It would appear that the general European war, which has been prophesied for so long past, and for which the armies and navies of the old world have long been preparing, is now at hand. Already the vast machinery of war has been set in motion by all the great nations, and the first blood has already been spilt.

"Of the conflict none can predict the outcome. Statistics of the numerical strength of navies or armies do not determine the conflict. With all the advance that has been made in the science of warfare, the personal elements is that which determines victory or defeat.

I"n Canada the spirit of defence of the British Empire is not less strong than in the Motherland itself. Thousands and thousands of Canadians have offered their services, and are prepared to leave all that is dear to them to fight for the Empire. And Strathmore, small though she is, will not behind with assistance when the call comes."1

The writer was certainly wrong about “personal elements” deciding victory or defeat. We know today that the war would devolve into a titanic siege, often likened to a voracious and insatiable mechanized slaughterhouse that consumed millions of men and entire nations, But he was indeed correct in saying Strathmore would answer the call. The very same day war broke out, Hugh Williams, a Strathmore man who had served as an officer in the Boer War, immediately telegraphed Ottawa declaring that 100 men were ready to enlist and awaiting instructions.2 100 on the first day - out of a population of less than 600.3

2. The Rush to Enlist

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 66

1926

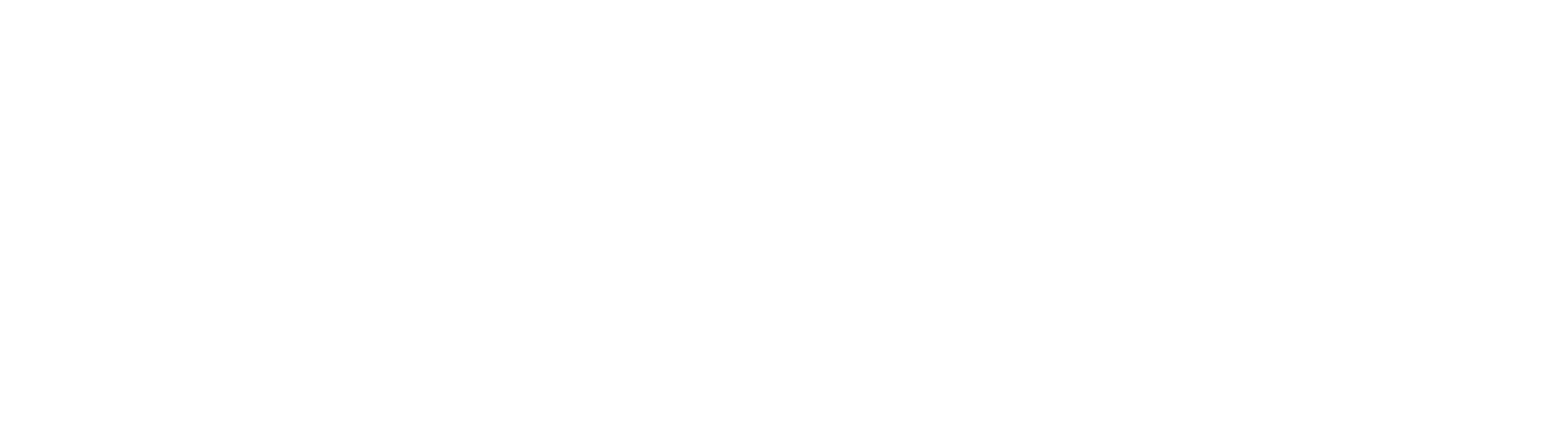

On the cenotaph are inscribed the names of 35 of Strathmore's sons who never returned from the war. Behind it is a German field gun that was one of thousands captured at the end of the war and hauled back to Canada to be put on display in every corner of the country. Most of them were melted down during World War II to make new weapons. After that war another plaque was added to the bottom with the names of those who died in the Second World War.

* * *

The Strathmore Standard recalled the festive atmosphere surrounding the departure of five local men in August 1914.

On Saturday five local men, W.G. Knyvett, D. Dempster, S. Williams, G. Greentree, J.C. Cockrell, left by the local for Calgary at 9.31. The news that they were going was spread about on Friday night, and consequently a big crowd turned out in the morning and gave them a hearty and enthusiastic send-off. They were driven down to the station in a flag covered motor car, and shortly before the train left the Strathmore Brass Band motored to the station and played several selections. As the train pulled out of the station the air resounded with the cheers of the assembled crowd.”1

There would have been fewer cheers that day if people had any grasp of the fate that awaited these men. Look up at the memorial in front of you. The names of three of those men, W.G. Knyvett, G. Greentree and J.C. Cockerell, are inscribed upon it. They never came home.

3. Why They Fought

1925

The final unveiling of the cenotaph in 1925. Strathmore is remarkable because every single eligible man who lived in the town enlisted in the military almost right away, the only place in Canada where this happened. What motivated them to risk their lives to fight in a war thousands of kilometres away which didn't threaten them?

* * *

In fact, those sentimental ties mattered a lot. Politically, Canada was still very much a part of the British Empire and standing aside was unthinkable. In 1910 Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, himself a Francophone from Quebec, spoke for most Canadians when he said “When Britain is at war, Canada is at war. There is no distinction.”2 The only way Canada could stay out of the war would be to dramatically declare independence from Britain and Dyer writes that in 1914, “nobody had that in mind, not even the most ardent of Quebec nationalists.”3

Most of the young nation’s eight million citizens were first or second generation British or French immigrants, and they still had deep emotional ties to the Old World. It was these men who were the first to enlist, while those with deeper roots in Canada were much less likely to join up. The Mississauga Horse, for instance, had six to eight British-born volunteers for every native Canadian.4

It’s no surprise then that the Western provinces, which had been most recently settled and had the highest number of British-born men, provided the army with its highest numbers of volunteers. Though the Western provinces accounted for just 20% of Canada’s population in 1914, they furnished fully 40% of the Canadian Army’s recruits.5

4. The Most Patriotic Town

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 119

1910s

The Anglican Church which was completed a few years before the war and no doubt the scene of many anxious prayers and sermons over the war years. The late summer of 1914 was marked with war themed sporting events as all the men prepared to go off to war.

* * *

“Canada had never been a military nation,” wrote John Mackenzie, the Strathmore Standard’s editor. “At the beginning the war was not taken too seriously. During a September celebration on the little [Kinsmen] lake at the front of the town, a mock naval battle was staged, Admiral Tirpitz being represented by a mild and innocent German in a rowing boat, and Admiral Jellicoe, who according to a popular verse of doggerel, 'would send the Germans to Hellicoe'. They pelted each other with flour bags until Tirpitz was 'sunk'.”1

Strathmore’s Serres Sadler later recalled, “My people were all very patriotic about the whole thing, and that. But I don’t think anyone expected it to go on as long as it did. I think, you know, in those days people thought the British Empire was pretty well invincible.”2

Perversely, most were more afraid of missing the action than losing life and limb. In December 1914, the Standard published a letter home by Sergeant Wilkins from Strathmore, who was serving in the British Army at the front. “We have not seen anything of the Canadian Contingent, who I believe are still having a holiday in England, they will have to hurry them up, otherwise they will not be here in time to get a medal.”3 Sergeant Wilkins would never make it home; his name is on the cenotaph as well

For these reasons Strathmore holds a unique place in Canadian history, a proud yet tragic honour. As Dyer writes, “the little town of Strathmore, east of Calgary, gained the distinction of being the most patriotic town in Canada. There, every eligible man joined the army in the fall of 1914, except one--and he went as soon as the harvest was over.”4

5. Bert's Letters

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 273

1920s

The Berry family posing for a photo on their tennis court which once stood on this spot. You can see the bank building in the background that still stands today. At centre are Ada and George Berry and their daughter Gladys. Their son Hugh is on the horse, and Gladys' husband Harold Morgan is at far left. This photo was probably taken after the war, as George and Ada's eldest son Herbert isn't present. The letters between Herbert and his mother as he was away at the front have been preserved and allow us to follow the story of this family through the war.

* * *

The Berry's were one of the more prominent families in Strathmore. Bert's father, George, ran the Strathmore Hardware Company and was a member of town council in 1914. George and Ada had high hopes for their children, and had sent Bert to Detroit University School and then to Toronto University. He was there completing his studies when war broke out. In 1915 he enlisted as a private with the Canadian Army Medical Corps. His brother Hugh, much to his chagrin, couldn't join up for medical reasons.1

Bert's story is representative of one major difference between the armies of all the nations in 1914 and our armies today: the more educated a young man was the more likely he was to join up. In Germany, for example, entire universities classes, egged on by their nationalistic professors, enlisted en masse. In November 1915 whole divisions of these hastily trained students were hurled at the British lines at Ypres, marching forward in ranks singing the German national anthem. The resulting slaughter is remembered in Germany as the "Kindermord", the massacre of the innocents. This was only a foretaste of what was to come. The war was to carry away a disproportionate number of the best and brightest in all the nations. The implications for Western society would be felt for decades to come.

6. Gallipoli

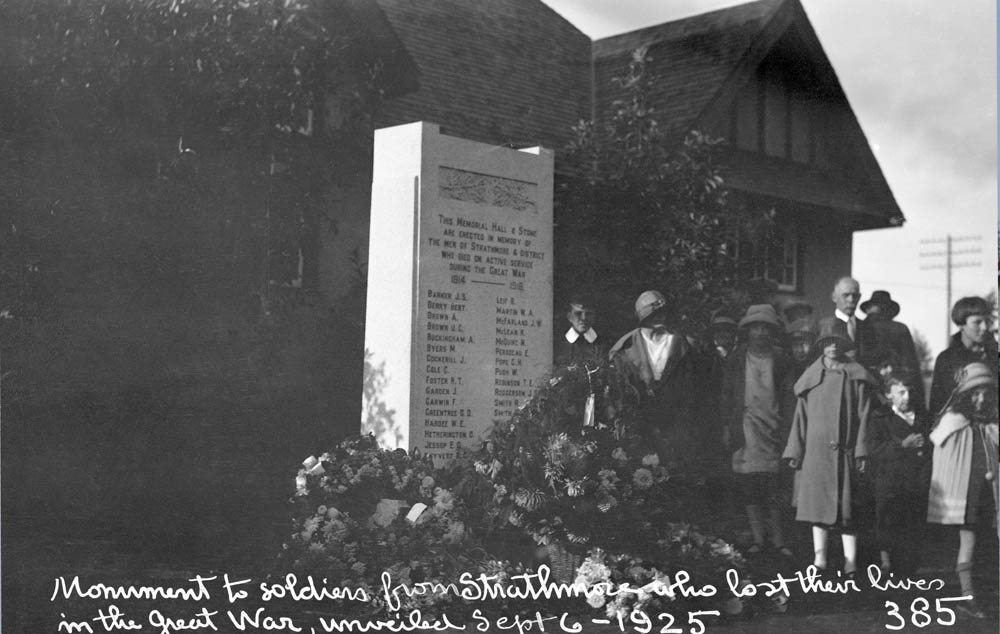

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 71

1910

The hardware store run by George Bert a couple years before the war. After Bert joined a field hospital unit he was sent to the Gallipoli front. The letters give one an impression of just how chaotic the situation was at the front, and how difficult it was for anyone - at the front or back in Canada - to figure out what was really happening.

* * *

Reports from the Peninsula are very conflicting. Some say they are making good progress and others say they are at a standstill so it is hard to know what to believe. This is a very difficult country to make progress in owing to it being one giant mountain after another. It doesn’t seem to me that the war can continue much longer - a year at the longest seems to be the general opinion - and the lord only knows that that will be long enough - in fact it would be just 12 months too long to suit me.1

His mother begged him to find out what had happened to Harold Morgan (seen in the previous picture), who was in love with Bert's sister Gladys. It was feared that Harold, who was with the British 29th Division, had been aboard the Royal Edward. The Royal Edward was a troopship carrying part of the division to Gallipoli front when it was sunk by a U-boat on August 13 with the loss of 865 lives.2

That Gladys was still trying to find out if her lover had drowned on the ship over two weeks after the event shows the chaotic and plodding pace that official updates about the men at the front were sent back to Canada. It's difficult to imagine how their families could continue to function back in Strathmore under this cloud of uncertainty.

Nevertheless Bert was, in a roundabout way, able to get something of an update about Harold:

I have been talking to a man who belongs to the Gloucester Infantry and he says that the Yeomanry were attached to them as infantry. Also that Harold will have been up on the Peninsula for about five weeks now - that is all he knew. So as I told Gladys - if she has not had any word from him not to worry too much on account of the difficulty of getting mail out from there. I will make further enquiries about him and try to let you know all I can but it is very difficult to ascertain anything here. This man also says that none of them were on the Royal Edward so that is a relief.3

And as in many of his letters, Bert reassured his mother. “I am fine and am taking the best possible care of myself and not doing any more than I have to - it's not wise to do so in the army - the less you do the better soldier you are.”4

7. Writing From the Trenches

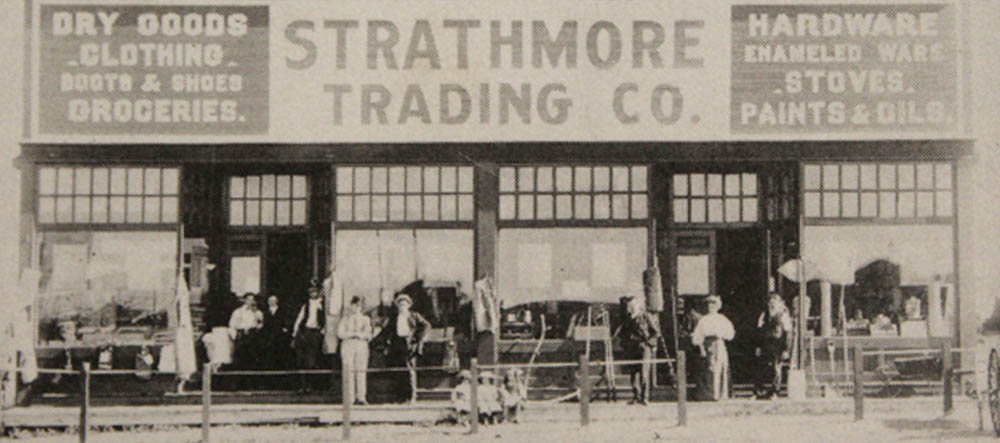

1917

White's Garage in the post-war period, admittedly not particularly related to the topic at hand. Ada's letters to her son are filled with updates about how things were going in Strathmore, while Bert made sure to leave out of his letters all the horrors of war in the trenches. They were hints though that Bert was being put - or putting himself - in danger.

* * *

Bert wrote home about his life and conditions, sharing with his mom stories about the moments of calm where he had a chance to take a nice warm meal and bath in a French town, or get a chance to ride behind the lines on one of his "two decent mounts." The quintessential Alberta boy, riding gave Bert great pleasure. Ada sent frequent care packages, so often that he has to plead with her to send less fresh underwear and boots to him as "there isn't a thing I need clean… However if you've already bought a pair dear, they won't go amiss."2

Ada's letters often included page after page about life in Strathmore - local gossip, farming conditions, family affairs - subjects that seem absurdly mundane to our eyes, given the epoch-shaping events Bert was taking part in. Yet these topics must have been a most welcome diversion to the young man, a connection back to his normal life and a reminder that not all the world had gone completely mad.

Bert only spoke of warfare in the vaguest way. Today the trenches of the Western Front are seared on our collective consciousness as a hellish place of unrelenting horror, but you wouldn't have guessed that from Bert's letters. He speaks of other men in his unit, of moving back and forth from the line, of hauling ammunition for his artillery guns and generally keeping busy. He does not speak about the mud, the terror, and the death.

In one dirt-flecked letter dated August 21, 1917, Bert can barely conceal his pride to announce that he's been recommended for a medal without giving any details about how it came about:

By the way dear I have been recommended for the Military Cross - please keep this entirely to yourself - in the family I mean as ten chances to one it won’t go through and I really don’t intend to mention it except that I thought you would have liked to know. You see I don’t want anything said about it unless it really goes through. Another officer and myself were recommended at the same time. Don’t please say anything about this until it really goes through for as I say dear it is very likely it won't happen."3

Ada's pride in her son must have been tempered by worries about what he had to do to earn such a distinction.

8. The Fighting Intensifies

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 85

1936

A woman plays with her dog after a massive dump of snow outside of the Superior Meat butcher. Over the course of mid-1917 Bert's artillery battery was constantly rotated in and out of the front lines. He was being assigned more dangerous jobs too, though he tried not very convincingly to calm his mom's fears. Where he was fighting, Passchendaele, there were few places to hide from mortal danger.

* * *

On September 5:

I am doing forward observing officer today - now don’t get anxious - as I’m in a very safe place - just as safe as I was in London. I’m in a tunnel way down under the ground at least 20 or 25 feet and have a peeking hole at the top of some stairs. I have a periscope to look through so I don’t have to show myself at all. Things are very quiet so it's like having a day’s holiday being here.1

As forward observing officer he was responsible for calling down pinpoint artillery strikes on German positions. There was no other man on the battlefield that the Germans would go to greater lengths to kill than the forward observation officer. He of course does not mention this to his mother.

By the 15th the constant battle is starting to wear him down and he looks increasingly eager to get leave and get out of the fighting, if only for a little while.

We now have a phonograph - a decca - and have some decent records so i'm playing it as I write and have it keep getting up to change the records. It's certainly a fine thing to have out here… I expect our Brigade will soon be out for a rest now - anyway I’m living in hopes. As soon as we do come out I’m going to apply for Paris leave.2

Throughout September rain saturated the crater-pocked battlefield and turned it into a bottomless morass of sucking, squelching mud. The exertion required to carry out even the simplest tasks was magnified many times over. And the mud didn't simply exhaust all those who had to fight in it - it was like bottomless quicksand. Hundreds are known to have drowned in it, sucked screaming into the quagmire while their comrades had to look on helplessly. To this day the word 'Passchendaele' can send a chill down one's spine. It was probably one of the worst battlefields to fight upon in all history.3 Bert doesn't mention the rain or the mud, but he does now begin mentioning the few breaks of sun they were getting to put a positive spin on things..

Please don’t mind the 1st sheet being torn but it slipped when I tore it out of the book. We are still having fairly decent weather which is a blessing, I hope it continues the same… Always with fondest love and kisses to you all, your loving son.4

Ada, reading between the lines of Bert's letters, was now urging him to plead sickness to get leave to Paris, even though she must know the censors will be reading her advice.

9. Return to Sender'

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 65

1916

Doctor John Giffen in front of his office after a great snowfall in 1916. He was one of the relatively few men left in the town between 1914 and 1918. In that time the families left behind carried on as best they could, all the time praying they would not receive the dreaded telegram informing them of the death of their loved one. For George and Ada Berry that awful day came in October 1917.

* * *

Bert Berry died of wounds sustained in the fighting on October 9, 1917.1 He was 23 years old. He was one of perhaps half a million men - British, Canadian, Australian, New Zealander and German - to become casualties in the battle.2

One can scarcely imagine the heartbreak Ada must have experienced at the loss of her son. It's hard not to conclude that the dried round splotches on those final returned letters are from the tears she shed as she reread the words herson never had a chance to read. The Strathmore History Book writes that Bert's death "was particularly hard for her to accept and she wrote often to Victor Sifton, a medium, in hopes that he could contact Bert for her through seances."3

The Berry family's tragedy was just one of many individual tragedies experienced by tiny Strathmore. 35 Strathmore men never came home from the First World War. Many others who came home were forever scarred physically or psychologically by their experiences.

The boundless optimism that so characterized the first years of Strathmore's existence were tempered by the loss of many of the most promising of the town's young citizens. All Alberta was affected: Of the 45,136 Albertans who went to war, 6,140 of them would die.4

When war came again in 1939, the people of Strathmore remembered the devastating toll of 1914-1918, and there were to be no patriotic celebrations.

10. World War II

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 73

1940s

The King Edward in the 1940s. Only 21 years after the end of the Great War, Canada was again drawn into a global struggle that promised to be every bit as destructive as the first. The article that ran in the Strathmore Standard announcing Canada's entry into World War II is fascinating to read today. It conveys the grave fear and anxiety felt by all Canadians, yet at the same time their grim determination to stand up and defend democracy in its darkest hour.

* * *

[Prime Minister Mackenzie] King was grave, his face lined, his lips trembling a bit, but his voice firm as he read to us from the announcement… The answer was no surprise, but it was epochal just the same. He did not say 'Canada is at war.'.. But he made it unmistakably clear that cabinet council had weighed the consequences and had decided that whatever Britain undertook to do in Europe, she would find Canada wholeheartedly by her side.

Premier Mackenzie King is a man of peace, a conciliator, a Christian. Only God knows what it is costing him to be the head of a state in a time like this when the sword is the appropriate weapon. But now that the maelstrom has swirled Canada into the orbit of world war, he will lead the country with all courage and devotion.

Despite the fresh memories of the horrors of the last war in Europe, Canadians were still fiercely determined to do their part. Writing from the time shows Canadians understood the threat Nazi Germany posed to world peace, and indeed civilization itself.

The issue is even clearer than it was in 1914 to the vast masses of people on this side of the Atlantic. The negotiations leading up to conflict have been followed almost hourly by persons in the most far-reaching parts of the country… He sees that an era of unopposed Nazi conquest would soon draw Canada within its orbit.

The government has no illusions about a cheap or easy victory. They prepare for a long and fearful conflict. But they are confident that might will be opposed by might, and that the democracies will survive any test to which they may be subjected.

11. War as Jobmaker

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 86

1953

Risdon's Ford dealership. In 1939 once again the young men, and increasingly women, of Strathmore rushed to sign up. Despite the huge toll of the First World War, more enlisted to fight in the Second World War than the First. The lingering impact of the Great Depression was likely part of the reason for this.

* * *

Yet that isn't what happened. Instead, once again, the people of Strathmore rushed to enlist. The Strathmore History Book records 152 Strathmore veterans from the First World War, but in the Second there are 175.1

The hangover from the Great Depression played a role in this. Drought and ongoing economic crisis that persisted through the 1930s hit Strathmore incredibly hard, affecting people's lives to an extent that is scarcely imaginable today. Average incomes in Alberta collapsed from $548 in 1928 to $212 in 1933 while total farm income went from $103 million in $5 million in the same period, completely crashing Strathmore's economy. Unemployment in Alberta peaked at over 30%, leaving many of Strathmore's citizens without work. These conditions more or less lingered until 1939 and the outbreak of war.2

Suddenly the government was pumping money into the economy to build weapons and enlisting tens of thousands into the armed forces where they would be provided food and pay. Many were only too happy for the chance at a job.

12. Defending Democracy

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 73

1940s

This is another view of the King Edward Hotel during the 1940s. The records from that time show that many of those who joined up during the Second World War did so - at least outwardly - for idealistic reasons. Students in 1940's Strathmore High School Yearbook wrote well thought out essays defending liberal democracy, showing why it was worth defending against the rising tide of fascism.

* * *

Swedish-born student Hilevi Nilsson's essay "Why I believe in Democracy" was published in Strathmore High's 1940 yearbook. "Democracy is slow," she wrote, "but true democracy is a sure method to solve our social and economic problems. It is the method of trial and error. Unlike the systems of dictatorship it provides a way to correct its own errors." She continued:

When war moves in, democracy moves out. At least we have not democracy as it should be. Therefore when we believe in democracy we should try our utmost to preserve it, and make it more efficient. That much can be done to increase the efficiency of democracy to meet our modern needs is unquestionable. The point however that must never be lost sight of, for a moment - perhaps a fatal moment - is that in trying to 'make democracy work,' we do not destroy democracy itself.1

It is particularly poignant that this clear-eyed analysis, outlining what makes democracy precious yet fragile, was published in the 1940 yearbook. Many of that year's graduates of Strathmore High would cross the ocean to fight and die in defence of these ideals.

The newspaper articles and documents like this make it evident the people of Strathmore knew that this war was not just the latest bout in the long running series of European wars, and Canada was no longer just a colony of Britain. This was a global struggle to defend our most deeply held values of democracy, freedom and the rule of law from the scourge of fascism, repression and hate.

13. Air Force and Navy

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 98

1920s

A car parked in front of Arnold Motors. During the Second World War the Canadian government put more emphasis on the air force and navy than the First World War in an attempt to keep more Canadians out of a bloodbath in the trenches. Thus many of Strathmore's men served as aircrew or sailors.

* * *

It's no surprise then that instead of the infantry, many of the 175 Strathmore men who enlisted (remarkably, it must be said, for a town of less than 700) joined the Royal Canadian Air Force, flying with Canadian squadrons in Bomber Command and Fighter Command.1 Many of these young men had grown up on tales of the spectacular exploits of world-renowned Canadian aces like Billy Bishop, who soared above the impersonal mechanized slaughter of the trenches and engaged in single combat with other pilots - like modern day knights. Many were likely inspired too by veteran fighter pilots who spent the 1920s and 1930s working as stunt pilots, performing death-defying aerial acrobats for awed crowds across the prairies.

Another major aspect of the interest in the air force was Alberta's central role in the Commonwealth Air Training Plan, a gigantic cooperative scheme to train air crews from Canada, Britain, Australia, and New Zealand. The Canadian Government invested a staggering $1.6 billion in the venture, $27 billion today, and set up around ten airfields across Alberta as training schools.2 Certainly some of Strathmore's men were drawn to the opportunities those presented. .

A number of Strathmore's men also flocked to Royal Canadian Navy, which may seem a bit surprising given that many of them had likely never seen the ocean before. Some commentators said that those raised on the prairies were well suited to the flat, lonely expanses of the North Atlantic, as in some senses they resembled the prairies.3

14. New Roles for Women

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 99

1923

Staff pose for a photo outside the Rexall Drug Store in 1923. There were relatively few jobs open to women before the 1940s, and those that did work were expected to stop as soon as they had married. The demands of the war meant the relaxing of many gender roles and the Canadian Women's Auxiliary Corps (CWAC) gave women a chance to serve in the military in a variety of support roles.

* * *

During the Second World War the opportunities for women in the armed forces were expanded with the formation of the CWAC, where they worked in the military as clerks, hospital assistants, storeroom workers, drivers and cooks. The CWACs were however paid ⅔ the wages of their male counterparts and only a few were sent overseas.1

About 4,500 Alberta women joined the CWAC, which offered adventure and the chance to contribute to the war effort.2 One of them was Strathmore's Margaret Gilkes. Gilkes would later write Soldier Girl, a novel based on her own experiences told through the eyes of Marjorie, one of the few CWACs stationed in England.

Marjorie had seen many of her friends join the Calgary Highlanders, and she didn't want to be left out of these history making events. "She had been nurtured on tales of British traditions of valour and honour and she knew she must go with the others to do her part for the empire and for the cause of freedom. Apart from her feelings of patriotism, she was thrilled at being a part of something big and heroic. This was her youth. This was was happening to her. She wanted to march with the others of her generation."3

The CWACs were a break from traditional women's roles in society, and many conservative parents had difficulty coming to terms with it. As Marjorie was bidding farewell to her parents to go to training, her father said

"'Marjorie, my dear child,' he said at last, 'take care of yourself away over there so far from our protection. Remember the things we've taught you. Say your prayers every night - and don't let anyone persuade you that in war time it's right to do things you would not do in times of peace. Your mother and I will always be thinking of you and praying for you.'

"Marjorie read the meaning of his words. He was telling her, delicately, that she must remain a virgin - that any relationship with a man outside of marriage was a sin."

15. Keeping England Fed

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 121

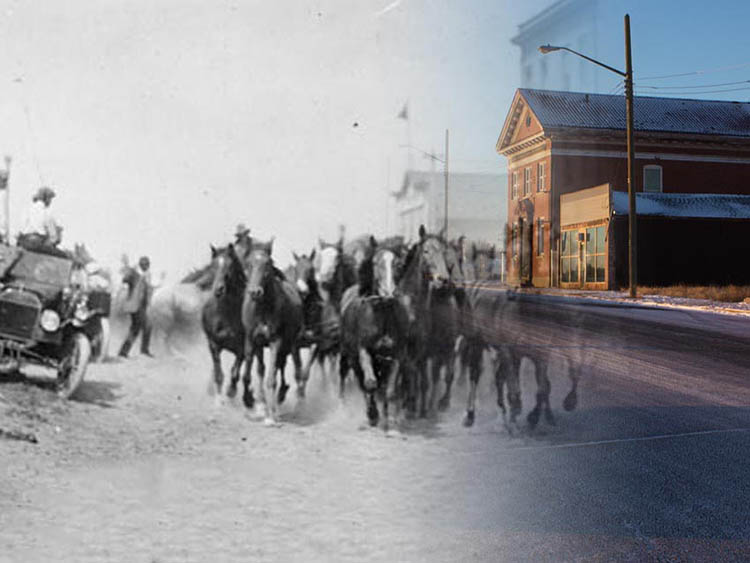

1940s

A fire-fighting acid tank is paraded down 2nd Ave as part of the Stampede parade. The prairies made a crucial contribution to the Allied war effort by ratcheting up production of wheat, cattle and other agricultural goods that supplied Britain and allowed them to continue the war.

* * *

As the noose tightened around the British Isles, Allied planners and German admirals factored the astounding numbers of wheat bushels and head of cattle coming out of the prairies into their calculations on how soon Britain could be starved into surrender. As Canada's agriculture minister James Gardiner told the House of Commons in 1940, "Wheat is the outstanding Canadian produce… the one material resource that is of greater importance than any other, in order that this war might be prosecuted to a successful conclusion."1

Thus the farmers who had not gone off to war were themselves an integral part of the war effort. They worked long hours and strained themselves to maximize production. To make up for the shortage of labour investments were made in new machinery and tractors became commonplace on the prairies for the first time. German prisoners of war were brought to Alberta to work on the farms, including some from a camp near Strathmore. The farmers' efforts were rewarded, and during the war Canada's agricultural production surged. It made a crucial contribution to Allied victory. It also hugely sped Alberta's transition to the mechanized agricultural system we have today and pushing the horse and plough into the background.

16. Invasion to Victory

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 66

1945

Strathmore's VE Day parade to celebrate the surrender of Germany. For Canadian troops the fighting reached its greatest intensity in the war's final year after the D-Day landings. In these final months many Strathmore men would pay the ultimate price. The victory they helped secure has allowed Canadians to live in peace and prosperity ever since.

* * *

"The hour has struck.

"The Invasion of France has begun with the greatest overseas forces to carry out military operations known in history. Troops of all kinds who have undergone the most rigid training ever given, are now face to face with the enemy.

"British, Americans and Canadians under the Command of General Montgomery, sometimes called the 'Wizard of War', have crossed the Channel and landed in France.

"Tossed into the scale are the lives of many thousands of determined young men. Britons, Americans and Canadians. Parachutists were the first to land in enemy territory.

"History has reached one of those terrible moments when neither pity nor good-will, nor hard thinking, nor hard working can alone find a way out. The way leads through death and wounds, through pain and sorrow. The ordeal by fire cannot be avoided.

"Today, June 6, 1944, the tide has turned. That there are hours and days of growing strain, no one needs to be reminded.

"We have known the Invasion had to come, but coming with it now to many homes will be the brief but final message - 'We regret to inform you-'

"Many a noble youth will make the supreme sacrifice in the cause of freeing Hitlerism from the World.

"Let all who name the Name of Christ, take up the Torch of these young men and act that this horror of war shall not re-occur."1

In the months after this ominous article many editions of the Strathmore Standard feature obituaries for local men killed in the fighting, like on September 14, 1944, when J.W. Meyers, a bomber navigator and "fine type of young man," was reported killed in action.2

When Allied victory finally came in 1945 it was greeted with jubilation. Strathmore had once again paid a high price: ____ had died. Nevertheless, the belief that the hard years of depression and war were finally past, and peace and prosperity were here to stay engendered a sense of optimism.

Strathmore had weathered the storms of the first half of the 20th Century, responding as few places in Canada had, and indeed in the First World War, to a higher degree than anywhere else in the country.

Endnotes

1. The Memorial Hall

1. "Armageddon," Strathmore Standard. August 5, 1914. (Edmonton: University of Alberta), accessed February 15, 2017, https://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SMS/1914/08/05/4/Ad00402_4.html.

2. "Local Jottings," Strathmore Standard. August 5, 1914. (Edmonton: University of Alberta), accessed February 15, 2017, https://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SMS/1914/08/05/1/Ar00103.html.

3. Strathmore History Book Committee. Strathmore: The Village that Moved. (Strathmore: Town of Strathmore, 1986), 47.

2. The Rush to Enlist

1. "Local Men For The Front," Strathmore Standard. August 12, 1914. (Edmonton: University of Alberta), accessed February 15, 2017, https://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SMS/1914/08/12/1/Ar00106.html.

3. Why They Fought

1. Gwynne Dyer. Canada in the Great Power Game: 1914-2014. (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2014), 42.

2. "Canada at War," Canadian War Museum, accessed February 15, 2017, https://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/going-to-war/canada-enters-the-war/canada-at-war.

3. Dyer, 40.

4. Dyer, 47.

5. Dyer, 48.

4. The Most Patriotic Town

1. John Mackenzie. Country Editor: 67 Years with weeklies on a Scottish Island and Canadian Prairie 1901-1968. (Rothesay, Scotland: Bute Newspaper, 1968), 45.

2. Gwynne Dyer. Canada in the Great Power Game: 1914-2014. (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2014), 49.

3. "In The Trenches," Strathmore Standard. January 6, 1915. (Edmonton: University of Alberta), accessed February 15, 2017, https://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SMS/1915/01/06/1/Ar00104.html.

4. Dyer, 47.

5. Bert's Letters

1. Strathmore History Book Committee. Strathmore: The Village that Moved. (Strathmore: Town of Strathmore, 1986), 273.

6. Gallipoli

1. G. Herbert Berry to Ada Berry, September 1915, Series 3 M-5756-26. Glenbow Museum Collections, Calgary.

2. "Deaths." Times of London. 6 Sept. 1915. The Times Digital Archive, accessed 15 February 2017.

3. Herbert Berry to Ada Berry.

4. Herbert Berry to Ada Berry.

7. Writing From the Trenches

1. "Supplement to the London Gazette." London Gazette. April 24, 1917. Accessed January 21, 2017.

2. G. Herbert Berry to Ada Berry, 1917, Series 3 M-5756-26. Glenbow Museum Collections, Calgary.

3. Herbert Berry to Ada Berry, August 1917.

8. The Fighting Intensifies

1. G. Herbert Berry to Ada Berry, September 1917, Series 3 M-5756-26. Glenbow Museum Collections, Calgary.

2. G. Herbert Berry to Ada Berry, September 1917,

3. David Stevenson. Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy. (London: Basic Books, 2005), 395.

4. G. Herbert Berry to Ada Berry, September 1917.

9. Return to Sender'

1. "Second Lieutenant George Herbert Bert Berry." Canadian Great War Project. Accessed January 24, 2017. https://www.canadiangreatwarproject.com/searches/soldierDetail.asp?Id=25480.

2. David Stevenson. Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy. (London: Basic Books, 2005), 395.

3. Strathmore History Book Committee. Strathmore: The Village that Moved. (Strathmore: Town of Strathmore, 1986), 274.

4. Howard Palmer and Tamara Palmer. Alberta: A New History. (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1990), 167.

10. World War II

1. "The Ottawa Spotlight." Strathmore Standard. September 7, 1939. (Edmonton: University of Alberta), accessed February 15, 2017, https://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SMS/1939/09/07/1/Ar00102.html

11. War as Jobmaker

1. Strathmore History Book Committee. Strathmore: The Village that Moved. (Strathmore: Town of Strathmore, 1986), 230.

2. Howard Palmer and Tamara Palmer. Alberta: A New History. (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1990), 244.

12. Defending Democracy

1. Hilevi Nillson. "Why I believe in Democracy." Strathmore High Yearbook 1940. (Strathmore: Strathmore High, 1940), 7.

13. Air Force and Navy

1. Strathmore History Book Committee. Strathmore: The Village that Moved. (Strathmore: Town of Strathmore, 1986), 130.

2. Gerald Hallowell. The Oxford Companion to Canadian History. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004), 579.

3. Donald Graves. In Peril on the Sea: The Royal Canadian Navy and the Battle of the Atlantic.(Montreal: Robin Brass Studio, 2003), 25.

14. New Roles for Women

1. Howard Palmer and Tamara Palmer. Alberta: A New History. (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1990) 297.

2. Palmer, 297.

3. Margaret Gilkes. Soldier Girl. (London: Century Publishing, 1986), 60.

4. Gilkes, 60.

15. Keeping England Fed

1. D'Arcy Jenish. "The Farmer's War." Legion Magazine, July 28, 2011. Accessed January 25, 2017, https://legionmagazine.com/en/2011/07/the-farmers-war/.

16. Invasion to Victory

1. "INVASION," Strathmore Standard. June 8, 1944. (Edmonton: University of Alberta), accessed February 15, 2017, https://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SMS/1944/06/08/1/Ar00106.html.

2. "Killed in Action - W.O. J.W. Meyers." Strathmore Standard. September 14, 1944. (Edmonton: University of Alberta), accessed February 15, 2017, https://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SMS/1944/09/14/1/Ar00103.html

Bibliography

Berry, Herbert to Berry, Ada, September 1917, Series 3 M-5756-26. Glenbow Museum Collections, Calgary.

"Canada at War," Canadian War Museum, accessed February 15, 2017, https://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/going-to-war/canada-enters-the-war/canada-at-war.

"Deaths." Times of London. 6 Sept. 1915. The Times Digital Archive, accessed 15 February 2017.

Dyer, Gwynne. Canada in the Great Power Game: 1914-2014. Toronto: Random House Canada, 2014.

Gilkes, Margaret. Soldier Girl. London: Century Publishing, 1986.

Graves, Donald. In Peril on the Sea: The Royal Canadian Navy and the Battle of the Atlantic. Montreal: Robin Brass Studio, 2003.

Hallowell, Gerald. The Oxford Companion to Canadian History. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Jenish, D'Arcy. "The Farmer's War." Legion Magazine, July 28, 2011. Accessed January 25, 2017, https://legionmagazine.com/en/2011/07/the-farmers-war/.

Mackenzie, John. Country Editor: 67 Years with weeklies on a Scottish Island and Canadian Prairie 1901-1968.Rothesay, Scotland: Bute Newspaper, 1968.

Nillson, Hilevi. "Why I believe in Democracy." Strathmore High Yearbook 1940. Strathmore: Strathmore High, 1940.

Palmer, Howard & Palmer, Tamara. Alberta: A New History. Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1990.

"Second Lieutenant George Herbert Bert Berry." Canadian Great War Project. Accessed January 24, 2017. https://www.canadiangreatwarproject.com/searches/soldierDetail.asp?Id=25480.

Strathmore History Book Committee. Strathmore: The Village that Moved. Strathmore: Town of Strathmore, 1986.

Stevenson, David. Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy. London: Basic Books, 2005.

"Supplement to the London Gazette." London Gazette. April 24, 1917. Accessed January 21, 2017.

Strathmore Standard Articles

"Armageddon," Strathmore Standard. August 5, 1914.Edmonton: University of Alberta, accessed February 15, 2017, https://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SMS/1914/08/05/4/Ad00402_4.html.

"In The Trenches," Strathmore Standard. January 6, 1915. Edmonton: University of Alberta, accessed February 15, 2017, https://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SMS/1915/01/06/1/Ar00104.html.

"INVASION," Strathmore Standard. June 8, 1944.Edmonton: University of Alberta, accessed February 15, 2017, https://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SMS/1944/06/08/1/Ar00106.html.

"Killed in Action - W.O. J.W. Meyers." Strathmore Standard. September 14, 1944. Edmonton: University of Alberta, accessed February 15, 2017, https://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SMS/1944/09/14/1/Ar00103.html.

"Local Jottings," Strathmore Standard. August 5, 1914.Edmonton: University of Alberta, accessed February 15, 2017, https://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SMS/1914/08/05/1/Ar00103.html.

"Local Men For The Front," Strathmore Standard. August 12, 1914. Edmonton: University of Alberta, accessed February 15, 2017, https://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SMS/1914/08/12/1/Ar00106.html.

"The Ottawa Spotlight." Strathmore Standard. September 7, 1939. Edmonton: University of Alberta, accessed February 15, 2017,