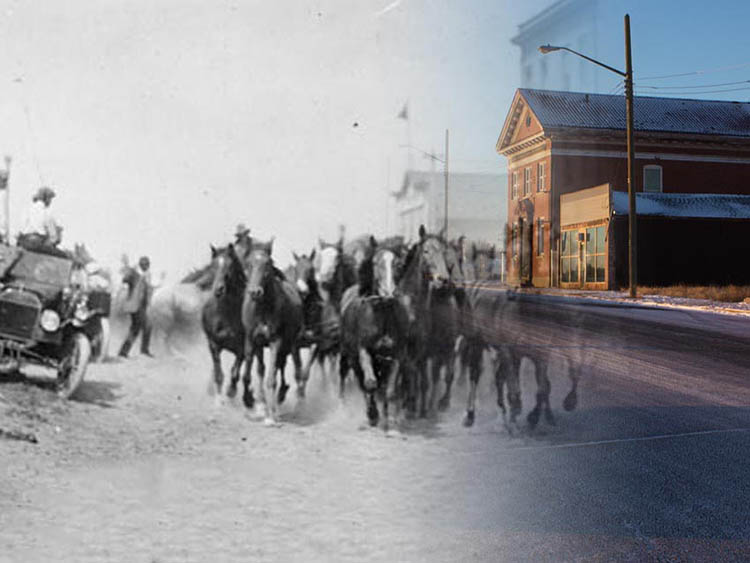

The village of Munson, is located just north of Drumheller in Alberta's Badlands region. As of 2021 it has a population of 170. The community was founded in the early 1910s, following the extension of the Alberta Midland line through the region. A ramshackle internment camp for enemy aliens was set up in some boxcars at Munson just after the First World War. The prisoners were made to work continuing the railway line, but a brutal winter, poor morale, and a massive outbreak of the 1918 influenza pandemic, led to the camp's ultimate abandonment.

This project has been made possible by a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

We acknowledge that Munson is on on Treaty 7 territory, the ancestral and traditional territory of the Blackfoot Confederacy: Kainai, Piikani, and Siksika, as well as the Tsuut’ina First Nation and the Stoney Nakoda First Nation. We recognize the land as an act of reconciliation and gratitude to those on whose territory we reside.

Donate Now

If you enjoyed this free content, we ask you to consider making a donation to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, which is providing urgently needed humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian people are heroically defending their homeland against a genocidal war of Russian aggression. The humanitarian situation is critical and the needs immense. 100% of all donations made through this link go directly to supporting the people of Ukraine. Recently funded initiatives by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation include demining and removal of unexploded ordnance, and the evacuation of thousands of deaf people from the warzone.

Explore

Munson

Stories

Munson Internment Camp

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Assoc.

The Munson Internment Camp was one of a network of 24 internment stations set up by the Canadian government during the First World War. The camp opened on October 13, 1918, just a month before the end of the First World War, but it did not close with the war's end. Instead it would stay open until March 21, 1919.

The men interned here were forced at gunpoint to do back-breaking labour laying railway tracks over the course of the freezing Alberta winter. Their misery was exacerbated by their living conditions: they were housed in overcrowded and poorly-heated railway boxcars; they had inadequate winter clothing; and their diet was inadequate, so hunger was a constant complaint. To make matters worse, the deadly 1918 flu pandemic swept through the camp, causing panic amongst guards and internees, and prompting many internees to risk escape.

As at the rest of Canada's internment camps, the men interned at Munson were so-called 'enemy aliens. In almost all cases they had committed no crime save being born in a country that Canada went to war with.