Walking Tour

The Canadian Pacific Railway

How a Railway Shaped Strathmore

Andrew Farris

In this tour we will see how the Canadian Pacific Railway and its institutions laid the groundwork for Strathmore. First the railway, which opened up this previously remote and isolated area to white settlement for the first time. The CPR wanted to do everything in its power to bring people to live and farm here so they built a massive irrigation scheme for the region, headquartered in Strathmore, and the demonstration farm to teach the new farmers how to survive. These institutions allowed Strathmore to flourish through much of the 20th Century. Since then the economic underpinnings of the town have evolved. The railway has disappeared, as has the demonstration farm, while the irrigation network has been turned over to the farmers. To a casual observer, it can be easy to forget the railway was ever here at all.

This tour will take you from the former site of the railway station, through Kinsmen Park and towards the Trans Canada Highway. You will have to cross the highway to reach the former site of the irrigation district and the demonstration farm.

This project is only possible with the generous sponsorship and support of the Western District Historical Society. We also owe thanks to the Town of Strathmore, the Strathmore Travelodge, and members of the Western District Historical Society.

1. Why a Railway?

1912

One can be forgiven for not realizing this nondescript spot was once the site of Strathmore's CPR station, heart and soul of the town of Strathmore at its founding in the 1900s. We start the tour here because settling this remote and sparsely populated place would have been incredibly difficult--if not impossible--without the railway. Yet Strathmore was but a tiny part of the titanic hopes and dreams heaped upon the railway by the young Canadian nation.

* * *

The HBC was reluctant to give up their highly lucrative monopoly and were widely "accused of promoting the image of the North West as a virtual wasteland to discourage settlement in order to protect the fur trade."1

Yet bigger forces of nation and empire-building were in motion that were beyond the HBC's control. The new Canadian government, along with its British overseers, had watched America's relentless westward expansion with apprehension. They feared America intended to fulfill its dreams of manifest destiny: control over the entire North American continent. If the Dominion of Canada (and the British Empire of which Canada was a part) was to keep the dream of a continent-spanning Canada alive, they needed to fill Rupert's Land with British farmers before the Americans beat them to the punch. Capitalists in Britain and Toronto were also eager to invest in the enormous mineral and agricultural potential of the prairies.

A sense of how remote the prairies were from the population centres in Ontario at this time can be gained by looking at the experience of the Wolseley Expedition, which was dispatched from Toronto in 1870 to put down Louis Riel's Red River Rebellion. The expedition's gruelling trek to Winnipeg across mountains range and raging rivers took almost four months. It is still considered by some historians to be amongst the most challenging in military history.2 After the railway was completed that same journey lasted a couple restful days.

The Empire's planners in London, who even after Confederation still held much sway over Canada's development, saw a further benefit in a cross-Canada railway. For centuries explorers had been searching futilely for the fabled Northwest Passage to connect Europe and Asia. A railway across Canada was just as good. They called it the "all-red route", after the red that coloured maps of the British Empire at the time.3

2. The CPR's Master Plan

1910

The historic photo was taken from about this spot, though the photographer was standing on top of one of the railyard stockhouses, or perhaps a train car itself, giving them the higher perspective. Though little evidence of the CPR exists here today, if you dig a little beneath the surface suddenly everything about this town bears hallmarks of the railway company's master plan. The town's location, its street layout, the locations of businesses and public buildings - even the town's name itself - were all set out by the railway company over a century ago.

* * *

In the early 1880s, in exchange for building the railway the CPR had been given 25 million acres of land of its choice, an area the size of South Korea.1 2 Within that area the CPR planned almost every aspect of the upcoming settlements down to the smallest detail, from the types of economic activity and industry that would take place, to the design of the towns, and the people that would be allowed to move in. A flavour of the giddy--almost megalomaniac--attitudes of the CPR planners is evident when the CPR surveyor (and inventor of timezones) Sanford Fleming, wrote "the station sites could best be selected in advance of settlement, before municipal or private interests were created to interfere with the choice and when engineering principles alone need be consulted… the present opportunity would never again occur."

The CPR, wrote one historian, "was faced with the unique opportunity to locate, create and shape urban centres on a massive scale… and retained an amazing autonomy in creating the urban landscape of Western Canada."4

This they went about with gusto. They laid out town sidings at 13 km intervals, separated by the distance it took a horse to haul a wagon of grain in a single day. Every other siding was destined to be a town. Strathmore itself began as Siding #16 west of Medicine Hat, though a Scottish engineer working on the line is credited with renaming it Strathmore.5

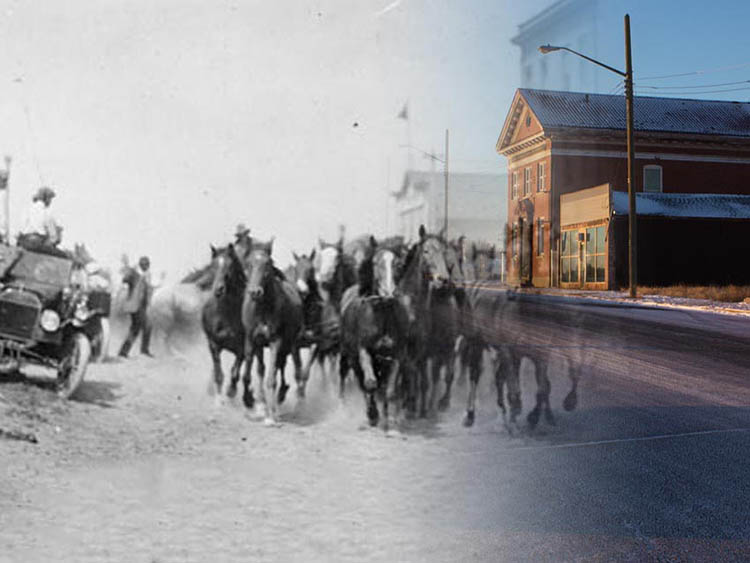

3. Ranching to Farming

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 88

1981

This photo shows the last train to depart Strathmore in 1982, a historic occasion that marked the end of this town's railway age. Shortly afterwards the tracks were dismantled and the grain elevators demolished. Yet when those elevators were themselves built over a century ago it marked the end of another era, one where the cowboys dominated these prairies and cattle ranching was the only business around. With the opening of the irrigation district ranching went into a steep decline as farmers moved in and began growing grain.

* * *

Palliser wasn't entirely wrong, and the CPR concluded the land around Strathmore would not be ready for farmers until a comprehensive irrigation system was built. For 20 years after 1883 then, Strathmore was not a town, but just a railway siding with a couple huts for the railway sectionmen. The land all around was given over to cattle ranchers, whose sprawling herds grazed on the prairie grass. When the cows were fattened up they were taken to the Strathmore siding and shipped to markets across the continent.

In the early 1900s this state of affairs began to change rapidly. In 1904 the long-planned irrigation scheme was finally put into action, and thousands of workers were brought in to build the huge system of ditches and canals that would comprise the Western Irrigation District which brought water to farmsteads all over the area and made farming possible. Strathmore was made the headquarters. In preparation for the arrival of the settlers, Strathmore was upgraded from a siding to a town, and actually moved from its previous spot, a few kilometres south of here, to the place you're standing now.

The farmers who poured into the region took over the prized irrigated land from the ranchers, and that industry fell into decline. Loss of grazing land, combined with severe winters from 1906 to 1908, meant that the golden age of the Alberta cowboy was drawing to a close. In 1906 there were 900,000 head of cattle in the province, but by 1909 this had fallen to 600,000.1

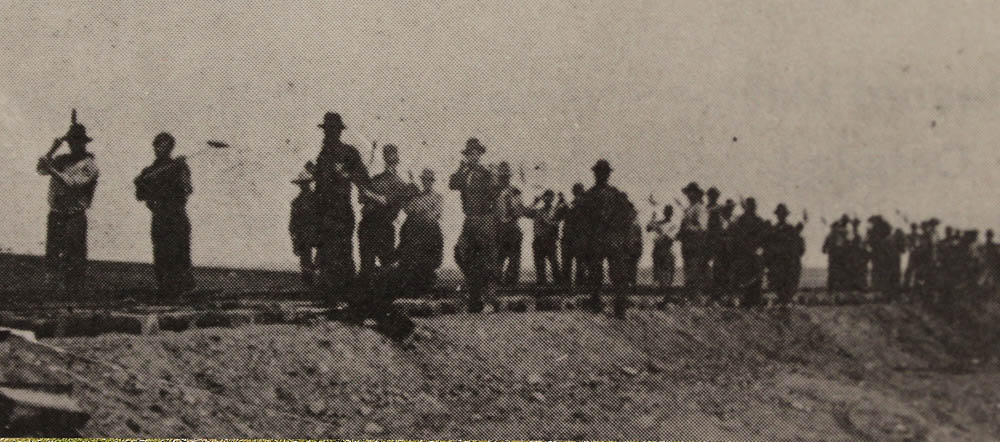

4. End of Track

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 10

1905

Workers at "End of Track" hammer in spikes and advance of the railway across the prairie. It's impossible to know where this photo was originally taken, though it does line up with our present day view well and gives one a good idea of where the tracks once ran through here. The railway workers, busy with their work, had little time to pose for photographs, and few photographs exist of the exhausting work of actually building the railway. As the track was laid through Strathmore on July 28, 1883, the workers set a Canadian record for the most track laid in a single day.1

* * *

"Thirty-two men and as many teams of horses unloaded 16,000 ties (from flat cars), loaded them on wagons and hauled them forward to place. There, eight men unloaded them and distributed them; four men spaced them; two others gave attention to spacing of ties to support the rail joints; and two more worked ahead of the spikers adjusting any ties that were misplaced.

"Twelve men unloaded rails from the supply train; twelve others placed them on the iron cars; four boys and two horses hauled the iron to the front; and twenty men, five on each side of each rail, unloaded and laid them in place. During the day these men handled 2,120 rails weighing 604 tons.

"Following came two distributors of joint bars, bolts and nuts. Next the bolters, fifteen of them each putting in and tightening up an average 565 bolts during the day, and the gaugers setting the rails the regulation distance apart.

"Four peddlers lay spikes on the ties then sixteen nippers placed them in position for the spikers, 32 in number driving home 63,000 spikes. And End of Track had advanced 6.38 miles across the prairie."

By the time darkness fell they'd made it to Serviceberry Creek and "nearly every team, together with men, were tired to death."2

5. Prairie Landmarks

1950s

The grain elevators that once stood on the other side of Kinsmen Lake dominated Strathmore's skyline. They too, were part of the CPR's plans to make farming viable in this area. However the CPR's monopoly on grain export angered the independent minded farmers and soon competitors like the farmer's cooperative Alberta Wheat Pool (the elevator seen in the photo) were set up.

* * *

The CPR began by concentrating grain collection points at its stations, building elevators at each station to hold grain ready for export. The elevators, standing five or six storeys tall, soon dominated the prairie landscapes. Van Horne himself championed the development of elevators that would also clean and grade the grain, ensuring only the best grain was exported. This would, he said, "reduce railway costs substantially, as well as enhance Canada's reputation for superior wheat and other grains."1

To meet the growing demands of the new farmers he also worked hard to expand the amount of rolling stock (railway wagons) available. In 1884 the CPR had a paltry 3,072 wagons available. By 1887 this number had risen to 9,000 was growing exponentially. By 1912, the year after Strathmore was incorporated as a town, the Angus Yards in Montreal were churning out 10,000 wagons a year.2

Trains became longer too, as locomotives were built with bigger and bigger engines. An 1880s locomotive weighed a meager 45 tonnes and could pull only a handful of wagons. By the late 1890s they had doubled in size to 98 tonnes. By the late 1920s huge 200 tonne "Selkirk" engines were being introduced into service, massively increasing the length of the trains that could be pulled.3

6. The Public School

Strathmore: The Village that Moved, 103

1912

Students post for a class photo in front of the Public School. The school that once stood on the site of this gas station was on land gifted to the town by the CPR.

* * *

7. The Western Irrigation District

1916

Hard as it may be to believe, this Mcdonald's stands on the spot of the CPR's Western Irrigation District headquarters. A person on horseback, and a man and his dog, are posing outside the striking building with it's skylight roof. It was from here that the great work of building and managing the district's irrigation system was carried out.

* * *

While farmers paid more for irrigated land, $18 to $30 an acre and annual water fees compared to $12 to $15 for non-irrigated, the benefit was quickly obvious when many non-irrigated farms were devastated by the drought of 1918.

The settlers in the WID were predominantly American farmers from the Western states seeking greener pastures. They were followed by English and Scottish settlers who arrived in groups of four to 12 families in trips arranged by CPR settlement offices in Chicago, Toronto, Montreal, Spokane and London.3

8. The Irrigators

1914

Though the landscape has been completely reshaped, this is--within a few metres--where the photographer was standing when they took this photo of a work crew stating out from the irrigation headquarters.

* * *

9. Learning to Irrigate

1910s

A man demonstrates irrigating a field. Behind him we can see the irrigation headquarters and the public school which were featured in previous stops. Irrigating a field by hand was back-breaking work, and a skill that was taught to the enthusiastic new farmers by the CPR's agriculture experts.

* * *

"The method of laying on the water was by damming up the water at the point desired to be irrigated with a homemade gunnysack sheet, supported on a pole, banking up the ditch for about ten feet back, and then, when the water had accumulated to within a few inches of the level of the dam, opening the bank and letting it out. The water by this means comes out with some force and goes over the ground quickly, which is one of the main points in successful irrigation. To cover the field thoroughly small furrows should be run from the main opening and these would carry the water thoroughly over the field."1

10. The Farmers Take Control

1914

A man tends to a demonstration plot of irrigated land. In the background can be seen the Strathmore Demonstration Farm. By the 1930s the irrigation scheme had accomplished its goal of promoting settlement around Strathmore. At the same time the CPR was losing money on the project, so in 1944 they turned over ownership to a farmer's cooperative.

* * *

P.W. Slater, a former manager of the WID wrote:

"The CPR was losing money on the system, and, as it has served its original purpose of land settlement, it was decided to close it down. A number of farmers became active, and to keep the water in the district, canvassed the district.

"They found enough interested landowners to form a district, so the Western Irrigation DIstrict was formed, and ratified by the Alberta legislature in 1944. We began operating it as a district on the first day of May, 1944. The district is owned by the water users, and operated by a Board of Trustees."1

This has been the case ever since, and that turnover of the irrigation system from the railway company to the farmer's coop marked one of the turning points in Strathmore's history.

11. A Farmer's Education

Bruce Klaiber Personal Collection

1920s

The Demonstration Farm's distinctive barn that once stood across this pond. The Demonstration Farm was another CPR-sponsored institution that played an important role in Strathmore's development. Staffed with agricultural scientists, the farm's mission was to provide a whole range of services to the hard-pressed local farmers for free or at the lowest possible price.

* * *

"In opening up their lands in the great Canadian West, the Canadian Pacific Railway has taken every precaution to safeguard the interests of the settlers… In fact, with ordinary and faithful application it would be hard for the average settler to fail.

"This educational work is undertaken by the company because the eyes of the world are upon Western Canada. It is indeed the "Last Great West", and thousands of settlers are coming to secure some land before it is all gone. They are coming from every walk in life, for all have the same desire, and that is, to secure a piece of land that they may call their own.

"Many who settle in Alberta have come from other climates, and other agricultural conditions and in a measure the Alberta soil, climate and general method of agriculture have to be learned again. So that we have all kinds of people coming from all kinds of agricultural conditions, and it certainly shows advanced ideas on the part of the CPR when they do all in their power to help all the various classes of settlers to be successful right from the start."

To help those farmers achieve these ends the Demonstration Farm gave out advice for free, such as the course in irrigation described above. They procured from abroad the best breeds of cattle, hogs and poultry to sell to the farmers at cost, embarked on ambitious (and often hugely successful) programs to breed improved strains of grains, fruits and vegetables, and grew orchards of windbreak trees to be sold at cost to local farmers.

12. End of the CPR Era

1920s

Another view of the Demonstration Farm, this time with the huge lettering on the barn's roof visible to passengers on passing trains which stopped by to take on fresh supplies for their trans-Canada journeys. The CPR was shattered by the depression of the 1930s, and as with the irrigation district, couldn't afford to continue running the demonstration farm. It was sold off in 1944. Battered by the rising popularity of the automobile, eventually the railway through Strathmore itself was shut down. While the railway, the irrigation district, and the demonstration farm were so crucial to Strathmore's development, except for the barn you see in front of you now (built after this historic photo was taken) and the irrigation system, there is no obvious evidence they were ever here.

* * *

As the farm expanded and plots of strawberries, sunflowers, potatoes and alfalfa were planted on the farm, the CPR's frequent tourist trains to the Rockies would stop in the town to take on fresh fruit and vegetables for their dining cars.

Like the Western Irrigation District, the Demonstration Farm was not a luxury the cash-strapped CPR could afford after the devastating years of the Depression. In 1944, the same time the WID was given over to the farmer's cooperative, the Demonstration Farm was sold to the Klaiber Family. They maintained many of the buildings over the years but by the 1970s most were falling into disrepair. A plan to turn the Demonstration Farm into a historical park never gained traction and most of the buildings were town down. Today all that remains is the one barn, one of the last built.

The final removal of the train tracks from Strathmore in 1982, as rail traffic had been rerouted south to the Strandmuir-Carseland cutoff, was the definitive end of the CPR era in Strathmore. Of the company that had played such a fundamental role in shaping almost every aspect of life in early Strathmore, barely a hint can be found today. Despite the loss Strathmore still grows and thrives today, but one can't help but look back and acknowledge those railway planners over a century ago who were the first to - quite literally - put Strathmore on the map.

Endnotes

1. Why a Railway?

1. B. McKee and G. Klassen. Trail or Iron: The CPR and the Birth of the West. (Calgary: Glenbow-Alberta Institute, 1983), 13.

2. S.J. Dawson. Report on the Red River Expedition of 1870. (Ottawa: Times Printing and Publishing, 1871), 54.

3. Ron Brown. Rails Across the Prairies: The Railway Heritage of Canada's Prairie Provinces. (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2012), 14.

2. The CPR's Master Plan

1. B. McKee and G. Klassen. Trail or Iron: The CPR and the Birth of the West. (Calgary: Glenbow-Alberta Institute, 1983), 18.

2. "Country Comparison: Area". CIA World Factbook. Accessed January 16, 2017. https://www.cia.gov/Library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2147rank.html

3. McKee and Klassen, 138.

4. McKee and Klassen, 138.

5. Strathmore History Book Committee. Strathmore: The Village That Moved. (Strathmore: Town of Strathmore, 1986), 4.

3. Ranching to Farming

1. B. McKee and G. Klassen. Trail or Iron: The CPR and the Birth of the West. (Calgary: Glenbow-Alberta Institute, 1983), 18.

4. End of Track

1. Strathmore History Book Committee. Strathmore: The Village That Moved. (Strathmore: Town of Strathmore, 1986), 7.

2. Strathmore, 10-11.

5. Prairie Landmarks

1. B. McKee and G. Klassen. Trail or Iron: The CPR and the Birth of the West. (Calgary: Glenbow-Alberta Institute, 1983), 109.

2. McKee and Klassen. 61.

3. McKee and Klassen. 60.

6. The Public School

1. Ron Brown. Rails Across the Prairies: The Railway Heritage of Canada's Prairie Provinces. (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2012), 44.

7. The Western Irrigation District

1. Mary Pharis. The Development of Irrigation in Southern Alberta.(University of Alberta, 1969), 28. Accessed January 15, 2017, https://www.demofarm.ca/water_haulers/pdf/history/History%20E.pdf

2. B. McKee and G. Klassen. Trail or Iron: The CPR and the Birth of the West. (Calgary: Glenbow-Alberta Institute, 1983), 16.

3. Strathmore History Book Committee. Strathmore: The Village That Moved. (Strathmore: Town of Strathmore, 1986), 13.

8. The Irrigators

1. Strathmore History Book Committee. Strathmore: The Village That Moved. (Strathmore: Town of Strathmore, 1986), 17.

9. Learning to Irrigate

1. "Irrigation Demonstrations." Strathmore Standard. July 1, 1911. Accessed January 16, 2017, https://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SMS/1911/07/01/1/Ar00104.html

10. The Farmers Take Control

1. Mary Pharis. The Development of Irrigation in Southern Alberta.(University of Alberta, 1969), 33. Accessed January 15, 2017, https://www.demofarm.ca/water_haulers/pdf/history/History%20E.pdf

11. A Farmer's Education

1. Strathmore History Book Committee. Strathmore: The Village That Moved. (Strathmore: Town of Strathmore, 1986), 22.

12. End of the CPR Era

1. Strathmore History Book Committee. Strathmore: The Village That Moved. (Strathmore: Town of Strathmore, 1986), 24.

Bibliography

Brown, Ron. Rails Across the Prairies: The Railway Heritage of Canada's Prairie Provinces. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2012.

"Country Comparison: Area". CIA World Factbook. Accessed January 16, 2017. https://www.cia.gov/Library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2147rank.html

McKee, B. and Klassen, G. Trail or Iron: The CPR and the Birth of the West.Calgary: Glenbow-Alberta Institute, 1983.

Pharis, Mary. The Development of Irrigation in Southern Alberta. University of Alberta, 1969. Accessed January 15, 2017, https://www.demofarm.ca/water_haulers/pdf/history/History%20E.pdf

Strathmore History Book Committee. Strathmore: The Village That Moved. Strathmore: Town of Strathmore, 1986.