Partner City

Sault Ste Marie

Dynamo on the Rapids

The rapids at the mouth of the Saint Mary's River have been the key factor in Sault Ste. Marie's history, and are in fact the reason the city is there at all. It's only fitting the city was named after them too: Sault is the 17th Century French word for 'rapids.' The place had for thousands of years been a place of great gatherings and bountiful fishing by First Nations peoples. The spot also had great strategic significance as the gateway to Lake Superior. French and later British fur traders set up a trading post here that continued until the 1860s. Near the end of the century, Soo, as its often called, was connected to the outside world with railways and canals, and the town became the site of great industrial enterprises that harvested the resources of northern Ontario's hinterland. Since then Sault Ste. Marie has grown steadily, and the downtown is reviving amongst the great stock of impressive historic buildings that survive.

This project is a partnership with the Sault Ste. Marie Downtown Association, the Sault Ste. Marie Museum, and Tourism Sault Ste. Marie.

We respectfully acknowledge that Sault Ste. Marie is on Robinson-Huron Treaty territory and is the traditional territory of the Anishnaabeg, specifically the Garden River and Batchewana First Nations, as well as Métis People.

Walking Tours

Downtown Sault's Murals

Showcasing Local Talent

Waterfront Attractions

Walking Sault's Boardwalk

The Sault Rapids

Engine of Sault Ste. Marie

A Stroll Down Queen Street

The Rise of Sault Ste. Marie

Explore

Sault Ste Marie

Stories

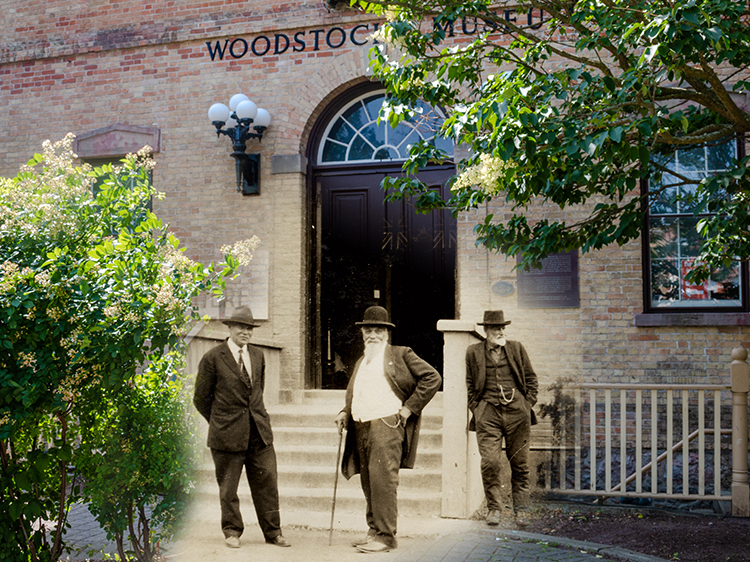

Sault Ste. Marie Receiving Station

During the First World War, Canada set up a network of 24 internment camps and receiving stations to process and imprison some 8,579 'enemy aliens' and prisoners of war. In Sault Ste. Marie, the federal building, which is now home to the Sault Ste. Marie Museum, became a receiving station for those immigrants from enemy countries. Between January 1915 and June 1918, some 43 enemy aliens were held here as they awaited transfer to other purpose-built internment stations, like the forced labour camp at Kapuskasing in northern Ontario.1 Some of those arrested locally were held in a small internment camp on nearby Whitefish Island, just opposite the locks of the Soo Canal.

By 1916 there were apparently 1,700 "enemy aliens" registered in Soo and required to report every week to the registrar. If they failed to report, or were found to be homeless or destitute when they did, they would be fined and, in some cases, interned at the Sault Ste Marie Receiving Station to await transfer to another internment camp.

Then and Now Photos

Militia at the Canal

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X2009.2.42

1903

A grainy photo taken showing the camp of the militia troops who came to Sault Ste. Marie to quell rioting by unpaid employees of Francis Clergue's insolvent business empire.

Soldiers Ending the 1903 Riot

Sault Ste. Marie Museum 2000.66.5a

1903

In the 1903 riot soldiers were brought in from Toronto to quell workers uprisings.

Commerce Bank Burns

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X978.16.31

1906

A crowd of people stnad around in the frigid temperatures watching as firefighters attempt to put out a fire in the Commerce Bank. On this occasion they appear to have been successful, as the building is still there (albeit in heavily renovated form).

The 1909 Locks Collision

Sault Ste. Marie Museum 994.84.8

1909

In 1909, a steamer approached the locks too quickly and rear ended another steamer, leading to a water overflow. The damage would close the locks until repairs could be completed.

Gore St. War Memorial

Sault Ste. Marie Museum 2008.60.19

1923

A large uncut boulder of Algoma rock was erected here in 1923 as a memorial to the men from northern Ontario who fell in the First World War.

Steaming Past Michigan

Sault Ste. Marie Museum 991.26.41

1944

A passenger steamer under full steam heads towards Lake Huron. Behind it you can see the American Sault Ste. Marie, including at the left part of the large electric hydropower facility the Americans had built in the 1890s. It was one of the first such facilities in the world.

A Man and His Son in 1907

Sault Ste. Marie Museum 992.4.20

c. 1907

Taking a drive in Sault Ste Marie in 1907 could have occured one of two ways. Ford cars had been rolled out some three years earlier, but a horse and carriage was still the primary form of transportation.

Postcard of a Steamer

Sault Ste. Marie Museum 992.2.5

c. 1910

A passenger steamer exits the locks heading towards Lake Huron. Notice the crowd of onlookers on the deck, marvelling at the canal. Passenger cruises were, and remain, hugely popular on the Great Lakes, and any of them that hope to get to Lake Superior have to go through Sault Ste. Marie, bringing a steady influx of tourists through the ice-free months.

Soldiers Preparing to Ship Out in 1914

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X982.12.4

c. 1914

Within two weeks of Britain declaring war on Germany on August 4th 1914, the first overseas contigencies left Sault Ste Marie.

Houses on Pim

Sault Ste. Marie Museum 2005.16.1c

c. 1920

You can see here a number of homes on Pim Street that have not survived, along with the Algonquin Hotel at the end of the block dominating the view. The Algonquin survives to this day, and is discussed in our Queen Street tour.

An Early Seaplane

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X978.16.79h

c. 1920s

A sepalane comes into dock near the canals. Given northern Ontario's numerous lakes, rugged terrain, lack of roads and airstrips, seaplanes were an obvious choice for moving around rapidly. Sault Ste. Marie became an important hub for seaplane activity, and it's no coincidence the Canadian Bushplane Heritage Centre is located just a short distance east of this spot.

Seaplane Dock

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X2000.5.28

c. 1939

This dock was once part of the Air Service Centre at Sault Ste Marie, where much of northern Ontario's aerial firefighting aircraft and bush planes operated out of.

Union Cab Depot

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X2014.1.2

c. 1940

Two women pose for a photo outside the Union Cab Depot that was once located at this spot on Foster Drive. Behind them you can see above them the famous Algoma's Friendliest City sign which survives today.