Walking Tour

Life in Early Calgary

8th Avenue

Elyse Abma-Bouma

Calgary Public Library pc 1881

While settlers from far and wide came to settle in Calgary in the late 19th and 20th centuries, this land was where the Plains First Nations lived, traded, and hunted bison for thousands of years. When European settlers eventually hunted the buffalo to extinction, some Indigenous peoples were forced to start ranching on their reserves in the surrounding areas.

Modern Calgary officially began with the building of the North West Mounted Police fort in 1875. By 1883 the Canadian Pacific Railroad reached Calgary, connecting this previously remote area to the rest of Canada and the world. The arrival of the railway was a truly transformative event, and brought with it an rush of immigrants from across Canada, Britain, and beyond. The next four decades were marked by explosive growth, taking the population from a few hundred in 1883 to 43,000 by 1911.1

This walking tour takes us down 8th Avenue, the heart of Calgary's commercial district for 140 years. Using photos from the period we will see what Calgary was like in those exciting days before the First World War, and we will examine some of the reasons i'ts become what it is today: a metropolis steeped in dreams of the West.

1. The Land of the Blackfoot

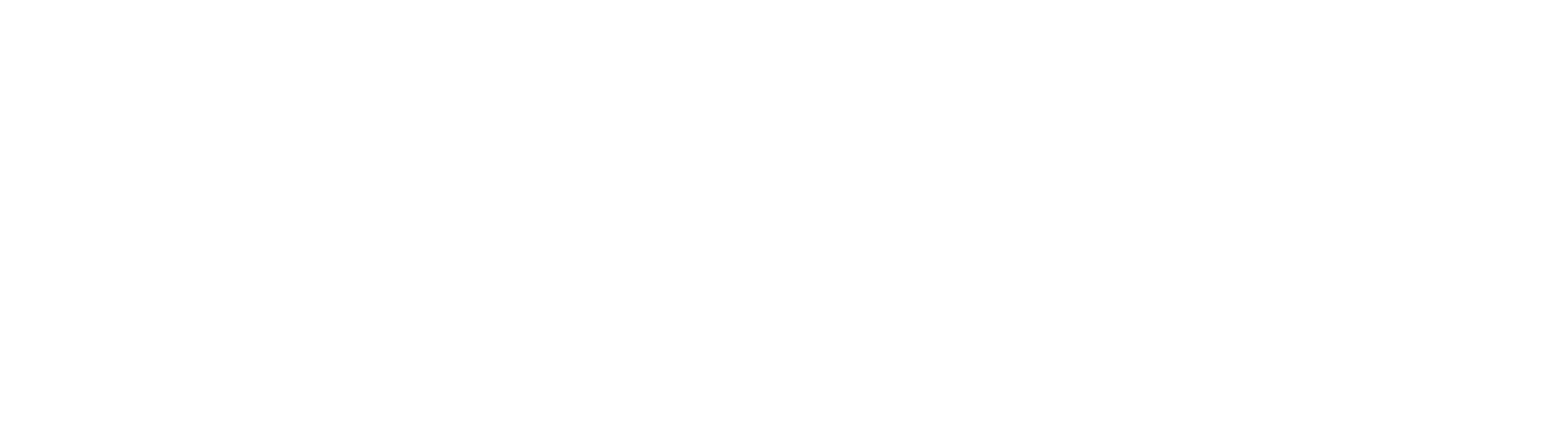

1887

This photo shows a party of First Nations people outside of Bannerman's Flour & Feed Store. Their horses are fitted with 'travois', a type of harness made of two crossed logs lashed together. The Plains First Peoples used travois for thousands of years to pull heavy loads, helping to sustain their nomadic way of life. They could be pulled by humans, dogs, and later--after their introduction by Europeans--horses. This technology often worked better than wheeled carts on the often muddy or snowy prairies.

After the establishment of Fort Calgary in 1875, stores and craftsmen set up shop on the adjacent prairie to supply the North West Mounted Police. The wooden buildings you see here on 8th Avenue were some of the first constructed, and would form the nucleus of the city's commercial district. Blackfoot People often came here from the surrounding areas to exchange and purchase goods to take back to their reserves and ranches.

* * *

White traders seeking buffalo hides and beaver pelts progressed into southern Alberta in the 1860s. In exchange, they offered the Blackfoots and Bloods blankets, metal implements, guns--and alcohol. It was illegal to trade or sell alcohol with Indigenous Peoples at the time, but enforcing this law on the unscrupulous whiskey bootleggers was impossible. Around 1869 'whiskey traders', as they came to be called, crossed the porous border from Montana into southern Alberta and set up 'Fort Whoop Up' where they began exchanging powerful, often adulterated, whiskey for furs.

Prior to European contact, alcohol was not a feature of Indigenous life on the prairies. In the late 1700s, traders brought whiskey to trade with the Blackfoot but found them unimpressed and uninterested; the Blackfoot perceived whiskey as a form of water and saw no sense in paying for it. Fur traders noted the Blackfoot's lack of enthusiasm towards liquor writing, "These people are not so far enervated by the use of spiritous liquors, as to be slaves to it." 1 The trading companies in the prairies were disappointed by the Blackfoot's lack of interest in a cheap and easily produced trade good. But the traders also had a highly cynical motivation: getting people drunk before a trade negotiation was a great way to come away with better terms..

So the traders persisted, the Hudson's Bay Co. and the North West Co. worked to make the Blackfoot reliant on spirits: they went so far as to make the drinking of spirits part of the trading ritual. Indigenous traders were blindsided by this new intoxicant, which put them at a disadvantage in trade negotiations.

This was the context the whiskey traders stepped into. Many were adventurers, mercenaries, and veterans of the US Civil War. Most treated the Indigenous with contempt and had no moral scruples about trading whiskey adulterated with dangerous chemicals.

The easy availability of potent alcohol contributed to outbreaks of lawlessness and violence. In 1873, a dispute between some Indigenous hunters and whiskey traders in the Cypress Hills of southern Alberta where "all parties were intoxicated" led to the whiskey traders massacring at least 20 Assiniboine men, women, and children. The murderers escaped back to Montana and never faced justice.2

A British army officer sent to investigate the Canadian West was shocked by what he found. The region, he wrote "is without law, order, or security for life or property; robbery and murder for years have gone unpunished; Indian massacres are unchecked even in the close vicinity of the Hudson Bay Company's poste, and all civil and legal institutions are entirely unknown.”3

In 1870, political authority over the Canadian West changed hands from the HBC to the Dominion of Canada, and the authorities quickly moved to get the "native population and unscrupulous whiskey traders" under control.4 5

In 1873, the North West Mounted Police (NWMP), the famous Mounties, were founded. Two years later, they had established Fort Calgary at the junction of the Bow and Elbow River, the nexus of the trade routes of the seven nations of the Blackfoot Confederacy.

Upon his arrival, a Mountie was unimpressed by what he found: "This is a miserable hole, nothing but two stores and a collection of whiskey shops."6 Fort Whoop Up was shut down and the modern city of Calgary quickly began to take shape.

A HBC land commissioner had a rosier outlook. "Calgary," he wrote "is the most charming spot I have seen in the North West so far, being a beautiful valley…The land is excellent—the grasses rich and thick—ample water—and wood not far off."7

The land commissioner's opinion makes it easy to see why the Blackfoot People were drawn to this place at the junction of the two rivers, and why hundreds of thousands of immigrants have made this place their home ever since.

2. Surviving the Boomtime

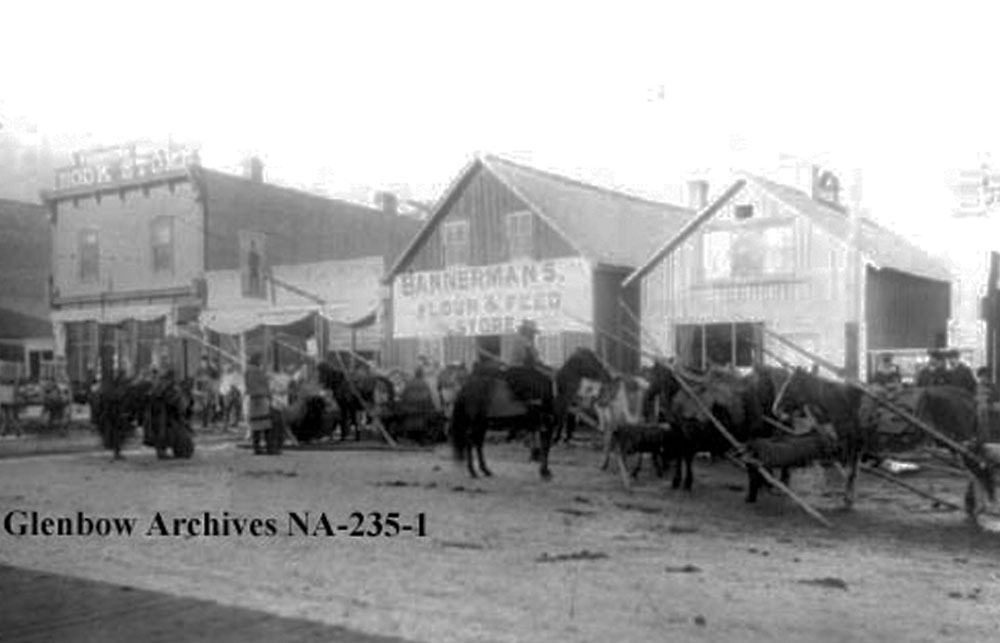

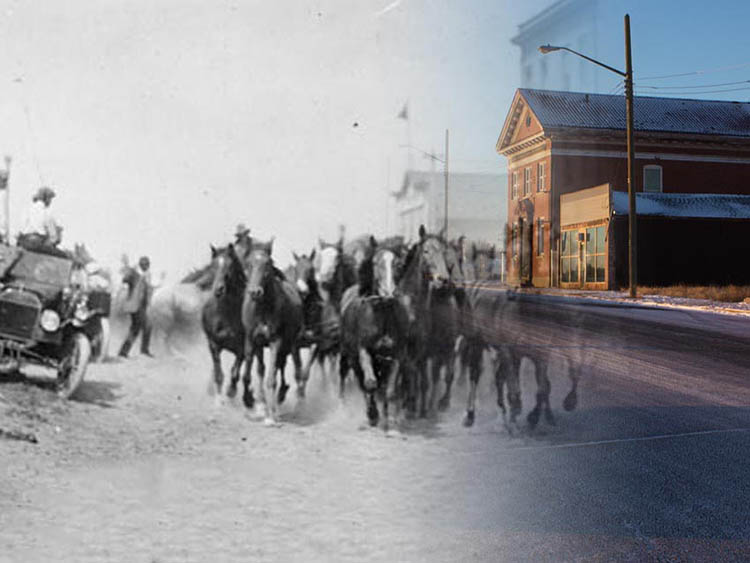

Calgary Public Library pc 1898

1910s

Looking down 8th Avenue from where you stand, you can see many surviving buildings from the early 20th Century. Though the businesses they've housed have come and gone, the stately commercial blocks illustrate the fundamental role this street has played in Calgary's development and are emblematic of the city’s rise from ranchland and rolling hills to a thriving city of business and capital. Just in this picture you can see the Victoria Hotel, the CBC building, a drug store, and the Hull Bros. butcher shop. These were all enterprises that contributed to Calgary's rapid growth and prosperity.

* * *

Merchant Isaac Freeze wrote to his wife:"[We] will build small store on as cheap a scale as possible...it is hard to tell how I will succeed out here but have hopes that I may succeed. At any rate shall work along safely."1 Freeze would go on to become one of the most successful businessmen in Calgary, despite his modest predictions, showing the entrepreneurial spirit that captured new Calgarians.

The little patch of wooden homes and businesses that grew up near Fort Calgary in the 1870s expanded rapidly in the early 1880s as people flooded into the community to service the eagerly anticipated Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR).

An early resident of the town observed that in 1882 there were "16 log shanties and houses, 9 Indian and 8 other tents." After just one year, during which the Canadian Pacific Railway reached Calgary, there were 107 houses, 50 stores, and 5 churches.2

This rocketing growth would continue, with some hiccups, for almost 40 years. By 1912 Calgary was one of the most populous and industrious cities in Canada.

For most who came to build new lives in Calgary during these boom years, life was hard. Paid labour in Calgary in the early 1900s was primarily for men. Most men worked as carpenters, bricklayers, or other general labour occupations making anywhere from $1.75-$2.75 per day, about $40-$60 per day in today's money. The cost of feeding a family of four far exceeded this amount, so children as young as ten were sometimes employed to make up the shortfall.3

Frontier societies like Calgary relied heavily of unpaid domestic labour. cooking, cleaning, laundry, and child care were all done by women who were generally unpaid. In 1911, while 18,505 males were employed, fewer than 3,000 females had paid work.4

Those few women who did work were often dressmakers, laundry ladies, or clerks, making the modern equivalent of $11 per day--a fraction the amount of their male counterparts. Elsie Barclay moved to Calgary with her husband and three children in 1912 after an unsuccessful attempt at homesteading further north near Lacombe. Though her husband worked drilling water wells, he could not make enough to support their family and Elsie put her dressmaking and furrier skills to good use, becoming a seamstress to supplement the meager family income.5

In addition to domestic labour, some women supplemented their income through prostitution. Prostitution was arguably Calgary's oldest occupation, alongside whiskey trading. The Nose Creek District, about 8 km north of where you stand, was known to be where some dressmakers and laundresses would go to ply their supplementary trade as 'ladies of the night.'6

Living and working in the prairies required hard work from everyone. Even if work was easy to find, it was often physically exhausting or dangerous, and for most it did not pay a living wage. To be part of the frontier culture was to be able-bodied, determined, and strong in the face of adversity.

3. Sandstone City from the Ashes

1912

The Hudson's Block seen here is just one example of the many sandstone buildings that can be found in Calgary. When a fire began near the corner of 9th Ave and 1st Street in 1886, Calgarians feared it would sweep through their whole city. It was a close call: after six exhausting hours, the volunteer firefighters and ordinary citizens finally extinguished the blaze. 14 buildings were left in ash, but fortunately no lives were lost.

The event awakened municipal authorities to the risk of fire, and officials began to construct all public buildings out of sandstone drawn from the nearby quarries. They encouraged residents and businesses to do the same. As you walk towards 1st Street you will see a wooden building, the only one in Calgary that predates the 'Great Calgary Fire.'1

* * *

As you may have noticed, Calgary can be a particularly windy city, a factor which amplified the threat of fire enormously. The local government saw the obvious risk, and had the foresight to buy a state-of-the-art horse-drawn fire engine in 1885. Unfortunately for Calgarians, a dispute over allegations of corruption in the mayoral election that year paralyzed government and nobody had got around to paying for the engine. So on the windy day of November 7, 1886, it sat gathering dust in a CPR freight shed.

When a fire began in a feed shop (no cause was ever identified though arson was suspected), strong winds fanned the flames: The conditions were ripe for disaster. "The fire spread rapidly," wrote the Calgary Herald afterwards. "In a short time the whole corner block on the south-west of McTavish Street and the Union Hotel across the road were in flames."2 The winds so common to Calgary pushed the fire further into Calgary fueling the blaze and exhausting the small fire brigade.

After the fire Calgary's municipal government leapt into action, developing a better water system, finally paying for the fire engine, and beefing up the fire brigade.

The fire's true legacy was not the property lost, but the way the city rebuilt. Rebuilding with wood invited disaster, but stone and brick were expensive. Calgary needed something close at hand to keep expenses down and rebuild quickly.

Luckily, a sandstone quarry just west of the town's core provided the much-needed material. Calgary began to build all public buildings out of the famous Paskapoo sandstone from these quarries. So many businesses followed suit that the town became known as the "Sandstone City". Within a few years over a dozen sandstone quarries were operating within Calgary's city limits, providing the means by which a great city rose up from the prairie grasses.3 As you explore downtown Calgary, you'll start to notice just how many of these sandstone buildings survive today.

4. The Evolution of Banking

1912

Right here, we're standing in front of the Molson's Bank building, which was constructed from sandstone around 1912. Though the building has changed hands and housed different businesses over the last century, its original function as a bank is still apparent via the inscription and the neoclassical columns and heavy sandstone facade, meant to symbolize permanence and security and popular with bank designs at the time. The Molson Family did indeed used to be in the banking business, but evidently banking just wasn't as lucrative as beer.

The Molsons had diverse business interests across Canada. By the early 20th century they had a brewing company, investments in the Canadian Pacific Railway, funded a public hospital in Montreal, and a bank.1

* * *

As Alberta's economy matured, these informal credit arrangements and networks were soon replaced by private banks to legitimize banking as a business. Eventually, charter banks with branches all across Canada arrived in Calgary and, as people became more dependent on credit, the banking industry thrived.3

5. The Role of Women

Calgary Public Library pc 1902

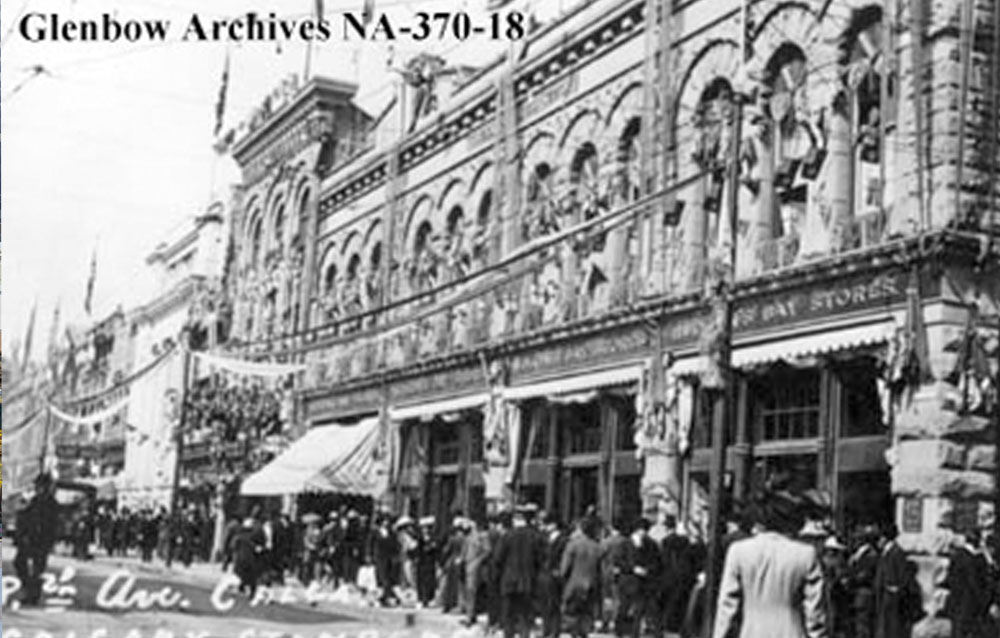

1910s

Looking down Eighth Ave. we can see how the street has transformed over the last century. Women and men strolling between shops gives us a glimpse into the candid everyday life of Calgarians in the early 20th century. In those days, Calgarians liked to view themselves as some of the most progressive people in Canada, but as elsewhere in Canadian cities, women were still subjected to subordinate roles and barred from participating in many aspects of society altogether.

* * *

The vast majority of women did not often participate in wage work or own their own businesses and as late as the 1920s only 3% of married women in Alberta had paid jobs.2 Yet this narrow metric ignores the absolutely crucial work practically all women engaged in. Women were responsible for caring for children, laundry, cooking, cleaning, tending to animals, and making clothing; though some women made a small wage providing domestic services, the vast majority went unpaid.3 Without the unpaid labour of women, families could not stay afloat and Calgary's economy would have failed quickly.

6. 150 Years of Change

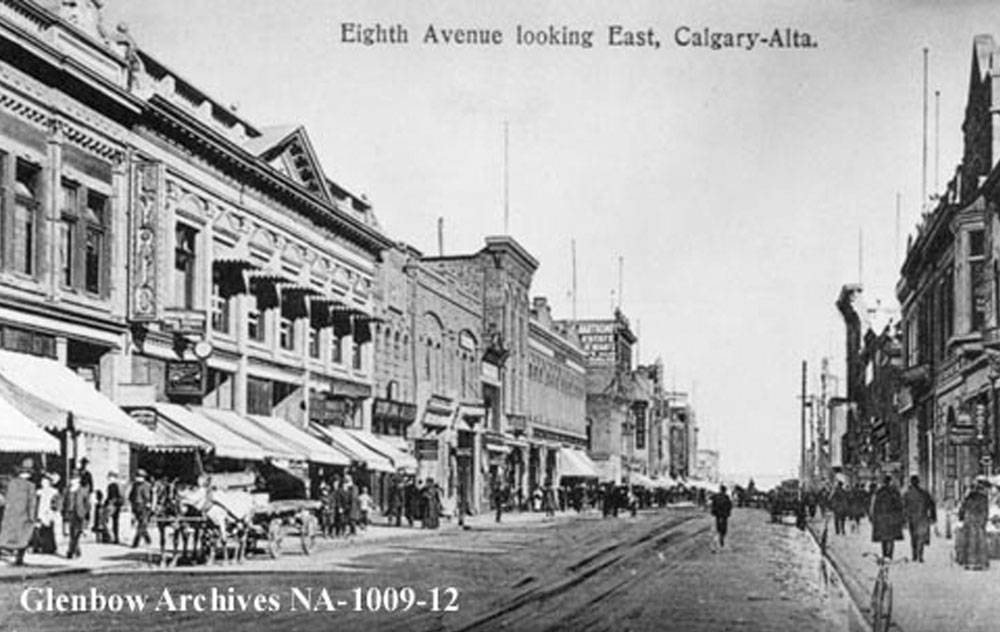

1910

This walk down 8th Ave has shown us different views of Calgary. From the hardships those who started out on the prairies faced to the whiskey traders and the beginnings of the North West Mounted Police fort. This city has experienced both boom and bust through fire and dust, rebuilding and reshaping with resilience throughout its history.

* * *

Endnotes

- 1. "Table I: Area and Population of Canada by Provinces, Districts and Subdistricts in 1911 and Population in 1901". Census of Canada, 1911. Volume I. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1912. pp. 2–39.

1. The Land of the Blackfoot

1.Hugh A. Dempsey, Firewater: The impact of the Whiskey Trade on the Blackfoot (Allston: Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 2002). 7.

2. Philip Goldring, "Cypress Hills Massacre," The Canadian Encyclopedia. May 31, 2013, last edited March 4, 2015. Online.

3. Edward Butts, "North-West Mounted Police," The Canadian Encyclopedia. February 7, 2006, last edited December 6, 2016. Online.

4. Dempsey, 8.

5. David Bright, The Limits of Labour: Class Formation and the Labour Movement in Calgary, 1883-1929 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1998), 17.

6. Henry C. Klassen, Eye on the Future: Business People in Calgary and the Bow Valley, 1870-1900 (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2002).

7. Glenbow Archives Macleod Letter 1874/02, September 28, 1874.

8. Klassen, 2-8.

2. Surviving the Boomtime

1. Klassen, 101.

2. Bright, 18.

3. Bright, 18.

4. Bright, 18.

5. Maxwell Foran.,Citymakers: Calgarians after the Frontier, (Calgary: Histor. Soc. of Alberta, Chinook Country Chapter, 1987), 249.

6. Bright, 20.

3. Sandstone City from the Ashes

1.Klassen, 235.

2. "Fire! Come at Last: $100,000 Worth of Property Consumed in 3 Hours," Calgary Weekly Herald (Calgary), November 13, 1886, 2003, online.

3. Management, Facility. "The Great Fire of 1886 and Its Effect on Future Building." City of Calgary. December 20, 2016, online.

4. The Evolution of Banking

1. "The Story Behind The label." Molson: Our Timeline. 2019. https://www.molson.ca/en/index.

2. Klassen, 120.

3. Klassen, 121.

5. The Role of Women

1. Sarah Carter. Imperial Plots: Women, Land, and the Spadework of British Colonialism on the Canadian Prairies. (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2016), 3-5.

2. Howard Palmer and Tamara Palmer. Alberta: A New History. (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1990), 234.

3. Bright, 38.

Bibliography

Bright, David. The Limits of Labour: Class Formation and the Labour Movement in Calgary, 1883-1929. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1998.

Butts, Edward. "North-West Mounted Police," The Canadian Encyclopedia. February 7, 2006, last edited December 6, 2016. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/north-west-mounted-police

Calgary Weekly Herald. "Fire! Come at Last: $100,000 Worth of Property Consumed in 3 Hours," (Calgary), November 13, 1886, 2003, peel.library.ualberta.ca.

Carter, Sarah. Imperial Plots: Women, Land, and the Spadework of British Colonialism on the Canadian Prairies. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2016.

Census of Canada, 1911. "Table I: Area and Population of Canada by Provinces, Districts and Subdistricts in 1911 and Population in 1901". Volume I. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1912. pp. 2–39.

Dempsey, Hugh A. Firewater: The impact of the Whiskey Trade on the Blackfoot. Allston: Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 2002.

Foran, Maxwell. Citymakers: Calgarians after the Frontier. Calgary: Histor. Soc. of Alberta, Chinook Country Chapter, 1987.

Goldring, Philip. "Cypress Hills Massacre," The Canadian Encyclopedia. May 31, 2013, last edited March 4, 2015. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/cypress-hills-massacre-feature

Glenbow Archives. Macleod Letter 1874/02, September 28, 1874.

Klassen, Henry C. Eye on the Future: Business People in Calgary and the Bow Valley, 1870-1900. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2002.

Management, Facility. "The Great Fire of 1886 and Its Effect on Future Building." The City of Calgary - Home Page. December 20, 2016. http://www.calgary.ca/.

Molson. "The Story Behind The label." Molson: Our Timeline. 2019. https://www.molson.ca/en/index.

Palmer, Howard and Palmer, Tamara. Alberta: A New History. Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1990.