* * *

Dating to the late nineteenth century, the site had been home to the Malleable Iron Works – a red brick symbol of the nation’s manufacturing-focused economy. Like many large Nova Scotian communities, Amherst was something of an industrial powerhouse. In addition to cast metal products produced by Malleable Iron Works, the town could also boast factories dealing in furniture, pianos, and woollen goods. The demands of a nation-wide rail network created many jobs for local residents. Railway rolling stock was produced for a time at the Malleable Iron Works plant under the auspices of the Canadian Car & Foundry Company until 1914, when the company closed down operations.1

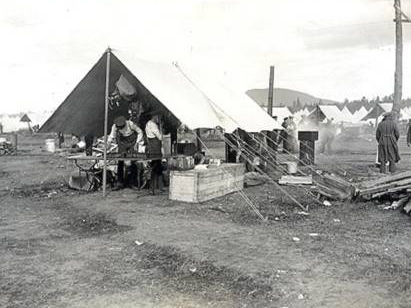

On April 17 1915, the Malleable Iron Works hummed to life again – but with a very different sort of workforce. “Enemy aliens” – so called because they were not regarded as naturalized British subjects, and were suspected of being in league with those nations that were at war with Britain and Canada – began arriving en masse at Amherst.2

The first contingent of prisoners hailed from a captured German vessel, the Kaiser Wilhelm Der Grosser; some 350 of that number had previously been held at a British prison in Jamaica. As originally configured, the Amherst facility could accommodate up to 650 prisoners of war. It was thus more than halfway filled to capacity by the time it marked its first month in operation, and by the time of its closure almost five years later, the site was housing 850 enemy aliens.3

Despite the increasingly overcrowded conditions, the Amherst internment camp was widely considered by Canadian authorities to be one of the better sites for internment operations. As one headline confidently put it, the internees “get very best meat, have widest liberties, and their grievances are such as could be found in any boarding-house.”4

Others thought quite differently. Not only was overcrowding an immediate problem facing prisoners and those responsible for overseeing them, crowded internment camps also reflected poorly on Canada and its place on the international stage. “The complaints continue to multiply,” noted a report in the August 23 1915 edition of the Toronto Daily News, “alleging that dust and dirt were allowed to accumulate, the lack of proper sanitary measures and generally unbearable living arrangements.” The report also took note of the “utter lack of privacy in their cramped quarters.”5

Seeking to verify the accuracy of these claims, an unidentified reporter was dispatched to the Amherst internment camp to investigate. After being shown through just about every part of the camp, and interacting with many of the prisoners, the reporter concluded that the accounts of unsanitary and overcrowded conditions were much overblown. “There is only this to be said of it,” he wrote. “If our Canadian boys, prisoners in Germany, are given as good treatment as these German prisoners in Amherst are getting, we and they have every reason to be satisfied.”6

Regardless of what this unnamed reporter claimed, Amherst was hardly a paragon of humane treatment insofar as internees were concerned. Indeed, an investigation made by David Bergstrom, the Royal Swedish consul-general, found the operation to be “very defective.”7

Not only was Amherst a domestic political football insofar as the overcrowding issue was concerned, it also became a hotbed of radical politics that gave hope to internees and worried authorities. Leon Trotsky, the noted Russian socialist, found himself interned at Amherst for several weeks starting in April of 1917. If Trotsky’s reputation didn’t proceed him, he would soon find a ready audience among his fellow internees. According to political historian Bohdan Kordan, Trotsky’s internment at Amherst “helped galvanize the prison population there, encouraging them to think of their private struggles in wider revolutionary terms.” Although his stay at Amherst didn't last long, Trotsky’s influence on the camp lasted right through to the end of internment operations: prisoners moved to Kapuskasing donned red ribbons in solidarity with those who felt a revolution was at hand.8

Fear of those harbouring political ideas thought to be unconventional played a significant role in the internment of “enemy aliens.” Up to sixty internees at Amherst were said to have been members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) – an international labour union known for its socialist and anarchist worldviews.9 IWW influences, together with Trotsky’s presence, ensured that Amherst would be at the forefront of political resistance to internment.

Through the sheer numbers of internees it housed in less-than-ideal conditions, Amherst became a symbol of both the financial and logistical problems associated with internment. An article published in the June 12 1918 edition of the Red Deer News noted that, according to a report commissioned by the Canadian Senate, the Amherst facility cost $202,393.40 to operate – more than any other camp.10 Originally intended to compensate for lack of space at the Halifax Citadel, Amherst quickly became yet another overcrowded nightmare. As Leon Trotsky noted in his memoirs, “The sleeping bunks were arranged in three tiers, two deep on each side of the hall. About 800 of us lived in these conditions...Men hopelessly clogged the passages, elbowed their way through.”11

Yet the Amherst internment camp also became a symbol of solidarity among those who felt that the political and economic system as it stood left much to be desired. While prevailing attitudes might have regarded “enemy aliens” interned in the old iron works as “radicals,” the town of Amherst would itself become a focal point of social and industrial unrest in the waning months of internment.

In May of 1919, a general strike shut down eight of Amherst’s largest industries and all but paralyzed the local economy for three weeks. As industry shifted to central Canada starting shortly before the First World War, those employed in Amherst felt left behind.12

For different reasons, both internees and local workers were victims of political, social and economic injustice. Though the Malleable Iron Works no longer dominates the surrounding neighbourhood in southeast Amherst, surviving photos of this once vast industrial complex paint a dark picture of how Canada regarded those who were “different.”

1. “The Great Amherst General Strike of 1919” SaltWire Network, last modified February 2, 2018, https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/federal-election/the-great-amherst-general-strike-of-1919-182792/

2. “Amherst Internment Camp,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, by Leo J. Deveau, last modified June 25 2021, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/amherst-internment-camp

3. Bohdan S. Kordan, “Political Choices and the Prerogative of State” in No Free Man: Canada, The Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016), 112.

4. “Amherst Prison Camp All Anyone Could Wish,” Toronto Daily News, September 4 1915

5. “Says Prisoners Are Ill-Treated Here,” Toronto Daily News, August 23 1915

6. “Amherst Prison Camp All Anyone Could Wish,” Toronto Daily News, September 4 1915

7. Kordan, “The Alien as ‘Enemy’” in No Free Man: Canada, The Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016), 227.

8. ibid, 266-267

9. “Industrial Workers of the World,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, last modified January 22 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_Workers_of_the_World

10. “Our Interned Aliens,” Red Deer News, June 12 1918

11. “When Trotsky was Interned in Amherst, N.S.,” Canadian Geographic, April/May 1988, 63.

12. “The General Strike in Amherst, Nova Scotia, 1919,” Acadiensis: Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region Vol. 9, No. 2 (SPRING/PRINTEMPS 1980), Pgs. 56-77