Walking Tour

The Peopling of Victoria

A Multicultural History

Alexa Dagan

Victoria Archives PR-0252-M06725

People have been drawn to the natural beauty and bountiful resources around Victoria for thousands of years. The Lekwungen people fished, hunted, and gathered here, setting up a complex society and shaping the landscape in ways that continue to have a profound impact today.

After the establishment of the trading post of Fort Victoria in 1843, the settlement quickly became a melting pot of different cultures as British, German, Japanese, Chinese, American, and Jewish immigrants--to name a few--set down roots. Multiculturalism was a defining feature of the city from its earliest days. Yet relations between these groups were far from harmonious, and it would be many decades before British Columbians would seek to address the racism and marginalization that was inflicted on many of these groups.

In this tour you will discover Victoria's rich history of multiculturalism, and learn about some of the different peoples that called Victoria home and what their lives were like. You will also learn about some of the challenges many of these groups faced--and continue to face--in achieving equality and acceptance in Victoria's society.

We'd like to thank the Victoria Archives for generous use of their historic photo collection.

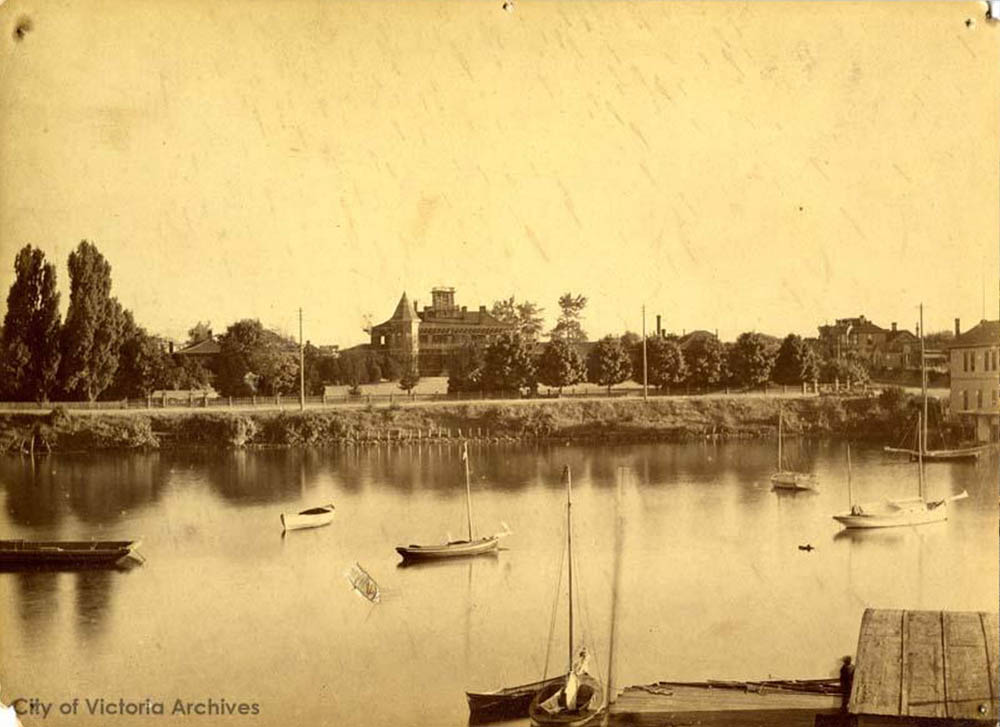

1. A Perfect Eden'

1859

This is one of the earliest surviving photographs of Victoria, showing the Inner Harbour in 1859, some 16 years after its founding as a Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) trading post. The decision by Europeans to first settle here was prompted by international politics; it was becoming clear that modern-day Oregon would soon become part of the United States and the HBC's major trading post there would come under American control. To prevent this, that post's Chief Factor, James Douglas, was tasked with finding a new location further north under that would remain in British territory. It needed to have a good harbour, access to fresh water, timber, and good agricultural land. When Douglas came first saw this place he knew he'd hit the jackpot. Writing to a friend, he said “The place itself appears a perfect 'Eden' in the midst of the dreary wilderness of the North."1 In 1843 Fort Victoria was established on this spot.

* * *

The Lekwungen harvested the exceptionally rich bounty of the lands around Camosack, enjoying a varied diet of fish, game, plants, and berries. The Lekwungen were not simply passive hunter-gatherers, but actively shaped their environment. Nowhere is this more apparent than in their practices for harvesting camas.

Camas is a starchy root vegetable that looks like an onion and tastes like a cross between a pumpkin and a pear. It was a vitally important foodstuff and trade item for the Lekwungen. When harvesting Camas they would only harvest the largest bulbs, leaving the others to encourage future growth. They would also start controlled burns of the countryside to wipe out competing plants and encourage the growth of fields of Camas. These fires created the open fields of the unique Garry oak ecosystem that still defines Victoria.2

These fields of wild camas caused James Douglas to tell a friend, "One might be pardoned for supposing [the land] had dropped from the clouds into its present position.”3 In 1846, a young HBC officer wrote that the lands around Fort Victoria were, "a natural park; noble oaks and ferns are seen in the greatest luxuriance... one could hardly believe that this was not a work of art. We were astonished at all we saw."4 Of course, it was not chance or act of God that created this landscape, but the Lekwungen's careful stewardship over thousands of years. The European settlers did not know this, or did not care.

To the homesick English colonists the camas seemed to indicate fertile agricultural land, and reminded them of the wildflowers of their homeland.5 To their intense disappointment, the soil was poorly suited for the kinds of crops--wheat, barley, corn--that Europeans relied upon. It would be many decades before the new inhabitants of Victoria finally came to understand the role the Lekwungen played in creating the 'Perfect Eden' they admired.

2. Fort Victoria

Victoria Archives PR-0252-M07427

1860s

This photo of Fort Victoria, taken from a second storey window sometime during the 1860s, showed the fort after the burst of expansion that came with the BC Gold Rush in 1858. The large building at the centre was the jail and courthouse, which no doubt housed a number of wayward miners. The original fort, built in 1843, was a much more humble establishment. Lieutenant Marvin Vavasour, of the Royal Engineers, described the Fort in a report to his colonel: "The Fort is a square enclosure of 100 yards, surrounded by cedar pickets, having octogonal bastions, containing 6 six-pounder iron guns at the north east and south west angles. The buildings are made of squared timbers, 8 in number, forming 3 sides of an oblong."1. The perimeter of the original walls and bastions of the Fort are memorialized in bricks laid into the ground of Bastion Square today.

* * *

During the early years, the Lekwungen had a significant role in the growing fort. They were eager to work for wages, and many held jobs as mail carriers, sheep herders, carpenters, and general labourers. Even more importantly, they traded food, a readily available resource, in return for blankets or money. While this arrangement worked well, Governor James Douglas soon felt the need to formalize this relationship through a treaty, in which the Lekwungen were to retain ownership of their village sites and camas fields, in addition to fishing rights, and hunting and gathering rights in unoccupied lands, while the Company would assume ownership of the land forming the District of Victoria. The indigenous population were given a one-time payment in the form of 371 blankets in a ceremony that mirrored the traditional Potlatch ceremony and therefore, in the eyes of the indigenous, conferred certain obligations regarding future gift exchanges. Only one side was to hold up its end of the bargain.4

While these arrangements temporarily increased the wealth of the Lekwungen, it also exposed them to devastating European diseases. This, in combination with the alcohol that settlers sold to the Lekwungen, which was distilled with salt water and often contained extraneous ingredients such as sulphuric acid, took a horrific toll. The local population collapsed from approximately 700 in 1850, to 182 in 1876.5 As Victoria grew, the Lekwungen could not protect their land in their weakened state, and were eventually relocated to a reserve in Esquimalt.

3. The Gold Rush

Victoria Archives PR-0252-M06090

1873

On Sunday morning, April 25 1858, the American side-wheeler The Commodore sailed into Victoria's Inner Harbour and dropped off 450 gold-hungry miners bound for the Fraser River. The arrival of this ship doubled the population of the small community overnight. This was only the first drop in a torrent that would balloon Victoria's population to 20,000 in a few short months and forever transform the city and the province.

Some of those who flooded into Victoria put down roots, setting up saloons and hotel bars that served liquor 24/7. Johnson Street, at the northern edge of downtown, was particularly notorious for its rowdy drinking establishments. Perhaps none of these saloons were quite as legendary as the California Saloon, pictured above. It was the most successful of all Victoria's American owned saloons, and certainly the one with the worst reputation.1

* * *

In addition to Bechtel, another of the saloon's characters was Annie Rooney, a transgender man who played the saloon's piano to entertain patrons in between brawls. Rooney had previously served in the American Navy before his birth sex, as female, was discovered.

The California Saloon was one of many drinking establishments that was erected seemingly overnight in 1858. As Victoria was the only seaport on the route to the Fraser, it was the first stop for those who were heading to the interior of British Columbia with dreams of fortune. These miners were mostly Americans fresh from the California goldfields, but some came from as far afield as Australia, South Africa, and China. Most of these new arrivals were only passing through Victoria, but some canny entrepreneurs established businesses that catered to the miners, and often made a great fortune in doing so.

The heyday of Victoria's saloons and hotels lasted from the gold rush until around 1917, when tighter liquor laws and eventually prohibition forced their closure. The California Saloon was hit hard by prohibition and shut its doors permanently in 1917. The building became part of the Salvation Army complex for a time, until it was eventually demolished.3

4. Canada's First Chinatown

Victoria Archives PR-0252-M06616

1890

Proceed into Market Square for this photo opportunity

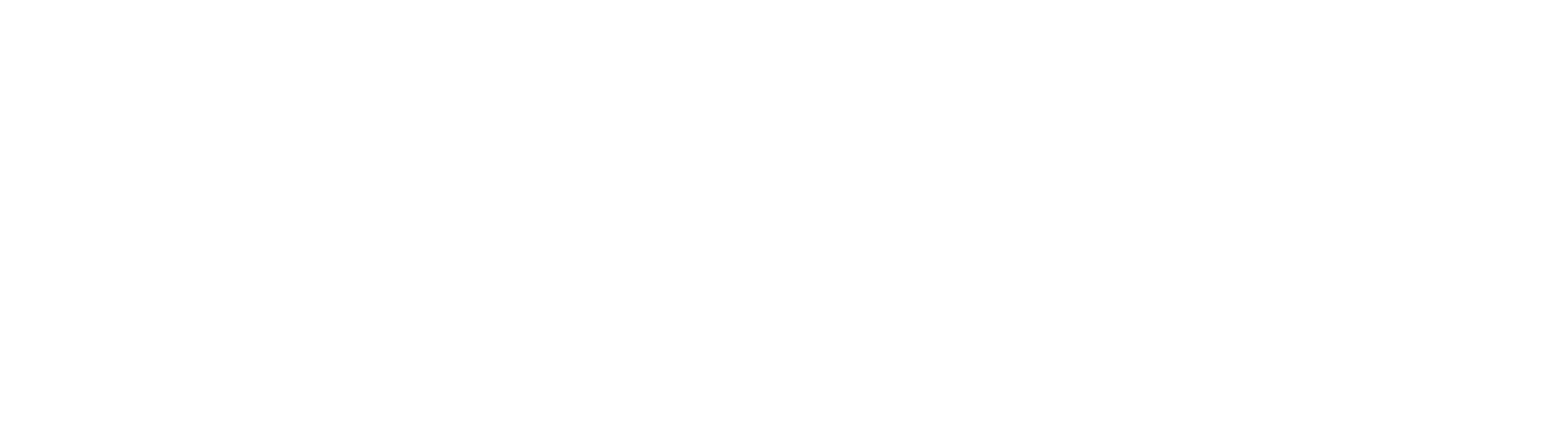

This photo shows the back of apartments that once faced onto Cormorant Street (now Pandora Avenue). This block that surrounds you was then the southernmost portion of Victoria's Chinatown, the oldest in Canada, and one of the best preserved in North America. Victoria was the main port of entry for Chinese immigrants to Canada in the 19th Century, and it grew to encompass much of downtown Victoria's north side.

* * *

These settlers mostly belonged to two groups: a small number of wealthy, educated merchants, and a larger group of impoverished agricultural workers. Both groups were overwhelmingly male. This photo shows the ramshackle state of some of these dwellings the lower class would have lived in.

Though despite the condition of the housing, Chinatown was thriving with Chinese-owned and operated businesses, and many of the poorer settlers found work as domestics, cooks, barbours, butchers, tailors and a variety of other trades.

Another trade brought visitors of all kinds to Chinatown: Opium. The drug was legal in BC until 1908, and produced in fourteen different factories in Chinatown in 1889. Men and women of all classes and backgrounds could be found partaking in the district's opium dens, which by some accounts were far less rowdy and dangerous than many of Victoria's saloons.3

Though an integral part of Victoria society, the Chinese experienced institutional and casual racism at the hands of the white majority. Many found life in Canada miserable and lonely. The onerous head tax meant few poor Chinese men could afford to bring their wives and families over to Canada, and so they often languished alone in Victoria's Chinatown. In 1919 an unknown Chinese man scrawled a short poem on the basement wall of a holding cell in Victoria's Immigration Building. It reads:

"I have always yearned to reach for the Gold Mountain. But instead, it is hell, full of hardship. I was detained in a prison and tears rolled down my cheeks. My wife at home is longing for my letter. Who can foretell when I will be able to return home?"4

5. The Fraternal Societies

Victoria Archives PR-0198-M06948

1921

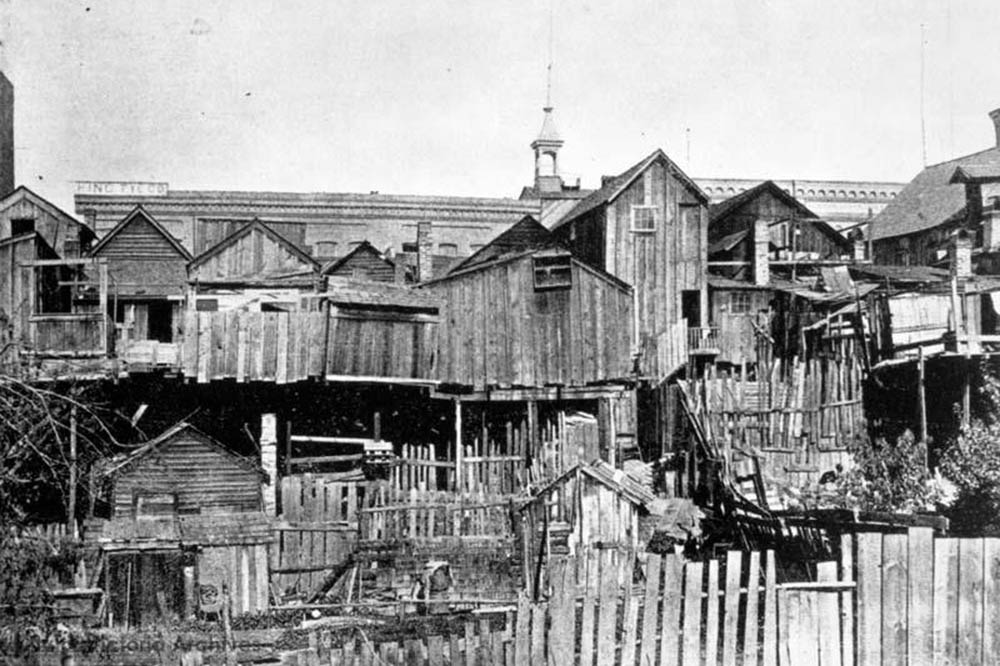

This picture shows the headquarters of the Chinese Freemasons. As immigrants from all over the world began lives in Victoria, they brought with them the societies and organizations that had helped bind their communities together in their homelands. Two such groups, the Freemasons and the Oddfellows, had a large presence in Victoria's early history, and their membership included many of the city's political and business elite.

* * *

The Chinese Masons were only one such group: the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Society (CCBA) also played a major role in the lives of Victoria's Chinese community. The CCBA was originally founded in response to anti-Chinese immigration policies enacted by the Canadian Government, such as the Head Tax (which forced Chinese Immigrants to pay first $50, and later $500 to enter Canada), and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923 (which effectively banned all Chinese immigration). The CCBA mediated with government at all levels on behalf of Victoria's Chinese, and worked to forward the community's interests, running schools and establishing the Harling Point Chinese Cemetery.

Perhaps most importantly, these societies and organizations provided a sense community and fraternity for recent immigrants often struggling in a new setting. The European Freemasons were not only a group for Victoria's elite, but was also a group that accepted members regardless of creed. Anglicans brushed shoulders with Victoria's Jewish and Catholic populations, and many of Victoria's Jewish pioneers were members. Due to the close relationship between these pioneers and the Masons, the society was given the honour of laying the cornerstones in the Congregation Emanu-el Synagogue, the oldest in British Columbia.2

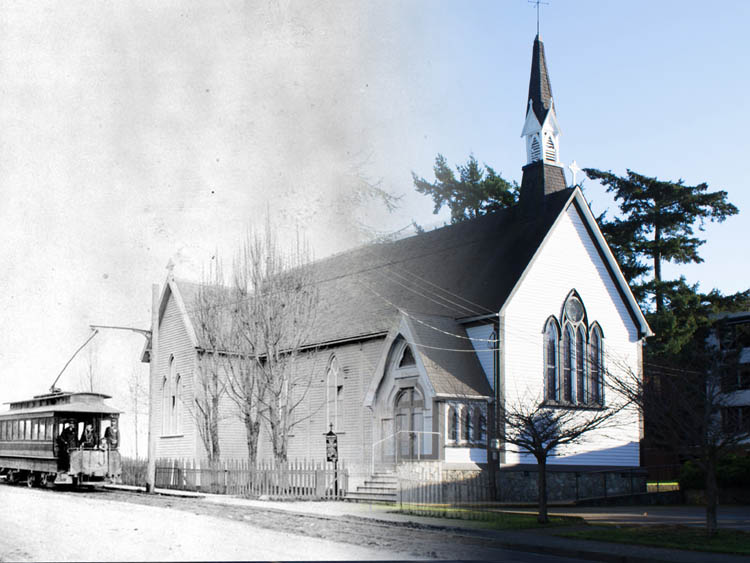

6. The Streetcars

1890

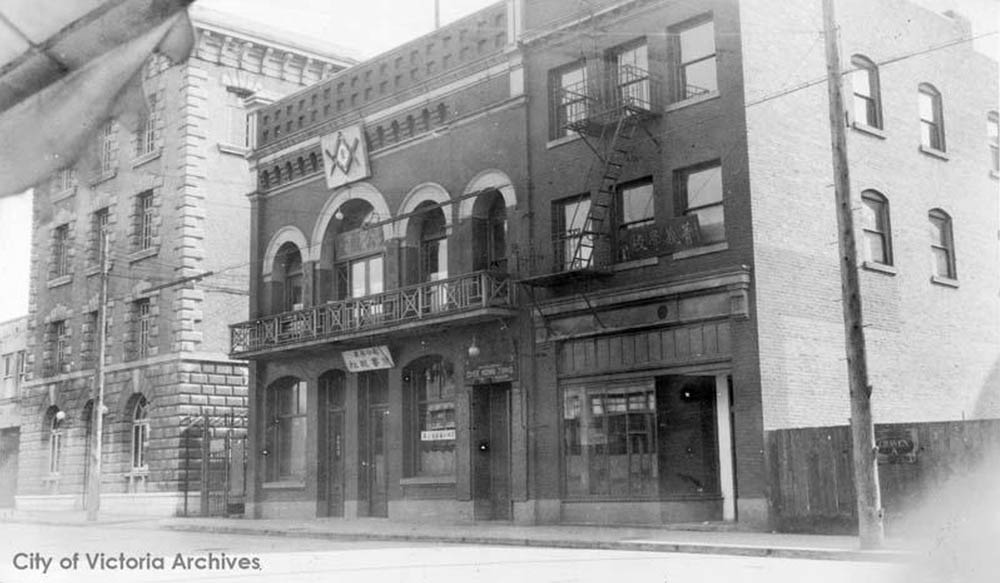

This photo shows a state-of-the-art streetcar on Government Street. Following the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway connecting British Columbia to the rest of the country, the previously isolated cities of Vancouver, New Westminster, Nanaimo and, Victoria all rushed to boost their presence on the national stage. Following the example of cities in Ontario, they quickly installed these streetcars that was key to boosting their prestige, and powering the expansion of the young cities into the suburbs. Victoria, despite its comparatively larger population and status as British Columbia's capital city, was threatened by the decision to end the CPR in Vancouver. Fearing it's eclipse as BC's prime city, Victoria's elites rushed to reassert the city's superiority.

* * *

Vancouver's move to modernize galvanized Victoria into action, and in just over a year Victoria's streetcars were opened to the public on February 22, 1890, beating Vancouver. Victoria was the first city in western Canada to do so, and only the third in the country outside of St. Catherines and Windsor.2

Despite the streetcar system's initial success, several factors contributed to its eventual closure in 1943. The system had been plagued by difficulty as it was bought and sold repeatedly to different electrical companies, and its reputation with the public damaged after the Point Ellice Bridge disaster that resulted in the deaths of 55 people.

Since the summer of 1892, the Point Ellice Bridge had been causing the National Electric Tramway company anxiety. Teredor worms burrowing into the wooden supports caused it to sink a few feet, but the city was slow to act upon the needed repairs.3 One year later, one span of the bridge sunk four feet while a streetcar was crossing, realerting the company to the imminent danger. Still the city failed to resolve the issue, and more alarmingly, failed to notify the streetcar company that the bridge was rated for vehicles weighing no more than ten tons.

On May 26, 1896 streetcar 16, bearing a load of twenty-one tons, attempted to cross the Point Ellice Bridge. About 35 feet into the crossing, the structure cracked deafeningly and dropped about a foot and a half. The streetcar, full of alarmed passengers, creeped another 15 feet further before the overencumbered bridge gave way, pitching 142 horrified people into the water, killing 55. It was the worst streetcar accident in North American history.4

This incident, immediately on the heels of an economic downturn, ruined the National Electric Tramway company. The City of Victoria, due to their gross negligence in repairing the bridge, was forced to pay over $150,000 in claims.5

In the years to follow, the high cost of maintaining the now extensive streetcar lines, the rise of the automobile, and Victoria's subsequent shift to double-decker buses, all contributed to the eventual closure of the system.

The streetcar era, while short-lived, coincided with the end of Victoria's heyday as BC's foremost city. The terminus of the CPR in Vancouver diverted visitors and immigrants to Victoria, and the city's growth slowed.

After the closure of the streetcar system, the cars continued to play a role in Victoria's landscape as they were repurposed across the Island, serving a variety of functions as chicken houses, diners, homes, and even a children's mini-theatre.6

7. The Great War

1916

This photo looks back down View Street, towards Government. This was before the Bay Centre mall was built at left. The photo was taken during the First World War, and the building at left houses an army recruiting station. Some 6,000 Victorians, 17% of the city's population, would enlist at recruiting stations like these and serve in Canada's armed forces.1 Though often overshadowed in popular consciousness by the Second World War, the First World War was the most traumatic and epochal event in the city's history.

* * *

One poem, written by a Victoria soldier and published in the Daily Colonist, gives a sense of the naive romanticism prevalent at the time:

"Don't think of death with fright; Old Fate with smirking glee, Hath spun her nickel bright.

She hides the coin from sight; It ain't for you and me To think of death with fright." - B. De M. Andrew of the 88th Fusiliers.2

The second largest ethnic group in Victoria was German, but in 1914 war was still seen as a gentlemen's game, not a struggle for national survival, so efforts were made to . That August an editorial in the Daily Colonist read:

"A local feature of the present situation is that we have living with us and playing an honorable part in our civic, business and national life a large number of Germans, whose sympathies may not unnaturally be with the country of their origin during these times of stress… Although their Fatherland may be at war, they are yet our friends and trusted neighbors and business associates."3

This feeling of comity was not to last. In May 1915 the liner Lusitania was sunk by a German U-boat. 1,200 drowned, most of them civilians, hundreds of them Canadian. Amongst the dead was Lieutenant James A. Dunsmuir, son of James Dunsmuir--a former premier and lieutenant governor of BC--and grandson of Robert Dunsmuir, the richest man in the province who had built Craigdarroch Castle.

The sinking was widely considered an act of uncivilized barbarism, and in Victoria the rage spilled out onto the streets. A mob roamed the city, smashing the windows of businesses with German names, or those known to be owned by ethnic Germans.

The anger and anguish was compounded by the mounting toll of a war was only meant to last till Christmas, but dragged on for years. Strict government censorship worked to hide the scale of the disaster from the public, but it could not conceal the expanding column inches listing the daily casualties at the front.

Despite the careful selection of soldiers' poems published by the papers, the ones that were published grew darker, and more realistic about the realities of war. The difference in outlook between the previous poem published at the outbreak of the war, and this one from near the end, could not be more stark.

"Crowded and close the wavering advance Crouches to burst of shrapnel overhead. Down thro' their ranks the high explosives dance. Hell's imps and outcasts dancing for the dead, All wreathed in smoke that ghoulish ballet there, Mocks these poor wretches who lie too still to care…" - Lieutenant Halley, Colonist, 13 March 1918.4

8. A Little Bit of Old England'

Victoria Archives PR-0007-M00723

1901

Government street is often one of the first stops when a visitor arrives in the city. This was just as true in 1901 when Government was draped in garlands and flags in honour of the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York's visit. Victoria was just one stop on an empire-wide tour for the royal couple, who would one day become King George V and Queen Mary. But, while this was merely one of many for the royals, for Victorians in this era, of whom about a third were born in Britain, this was a seminal event to celebrate their close ties to the British Empire. It was the First World War that would begin Victoria's shift away from its British identity, and towards a Canadian one.

* * *

Victorians carefully shaped the city into a 'Little England'. They tended English gardens. Officials named the streets after their hometowns and shires. Archaeological findings of bottles and ceramics from this period show that Victoria residents actively sought out British products, out of a sense of loyalty and nostalgia, even though comparable American products were more cheaply and readily available. They sought every opportunity to demonstrate their loyalty to the mother country, and sought to construct a new society based upon the old one.

Yet, when Carr's father returned to England, he soon found that the real thing failed to hold up to the nostalgic ideal of his memories: He'd forgotten about the stuffy English obsession with class that permeated British society, and preferred the more egalitarian American view of class consciousness (or lack thereof) that Victoria had adopted.1

It was the First World War that would put huge strain on many Victorians self-identity as aspiring Englishmen.

The first Canadian troops arriving in Europe found themselves looked upon with contempt by British officers, who dismissed them as uncivilized colonials. Canadian units were put under British command, and because class was more important than merit for promotion in the British Army, many British generals overseeing the Canadians proved themselves incompetents, distinguished only by their proper breeding. It was these British generals who have helped create the common perception that Allied armies in World War I were 'lions led by donkeys.'

When the Canadians were allowed the latitude to conduct battles as they saw fit, they--along with the Australians and New Zealanders--proved themselves the most formidable units on the Western Front. Victoria produced the finest general in Canadian history, and one of the most effective of the war, the former Vic High teacher and Victoria realtor, Arthur Currie--a man who would almost certainly never would have achieved senior rank in the British army, on account of his inferior social standing.

By the end of the war 14% of all males in BC between the age of 18 and 50 had been killed or wounded. Many more would forever bear the mental scars of the hell they'd lived through, a whole society traumatized by what we today call PTSD, but was then barely understood. Many of those returning held British commanders at least partly responsible for the waste of lives.

Thus it was a combination of disillusionment with British leadership, and the repeated triumphs of the Canadians Corps fighting together, that was vital in forging the modern Canadian identity. Battles like 2nd Ypres, Hill 70, Passchendaele, the Hundred Days, and Vimy Ridge, victories won by the blood of men from Halifax to Victoria, cemented the young nation together. The First World War was Canada's crucible, and decisively shifted the attitude of Victorians, who increasingly saw themselves not as subjects of the King and Empire, but as Canadians.

Victoria's strong British identity would nevertheless continue to play a major role in the city's image, especially as it became the main focus of an aggressive tourism campaign after the war that marketed the city as a "Little bit of old England." But if you were to ask a Victorian today if they were a British or a Canadian first, the answer would be obvious--the question absurd.

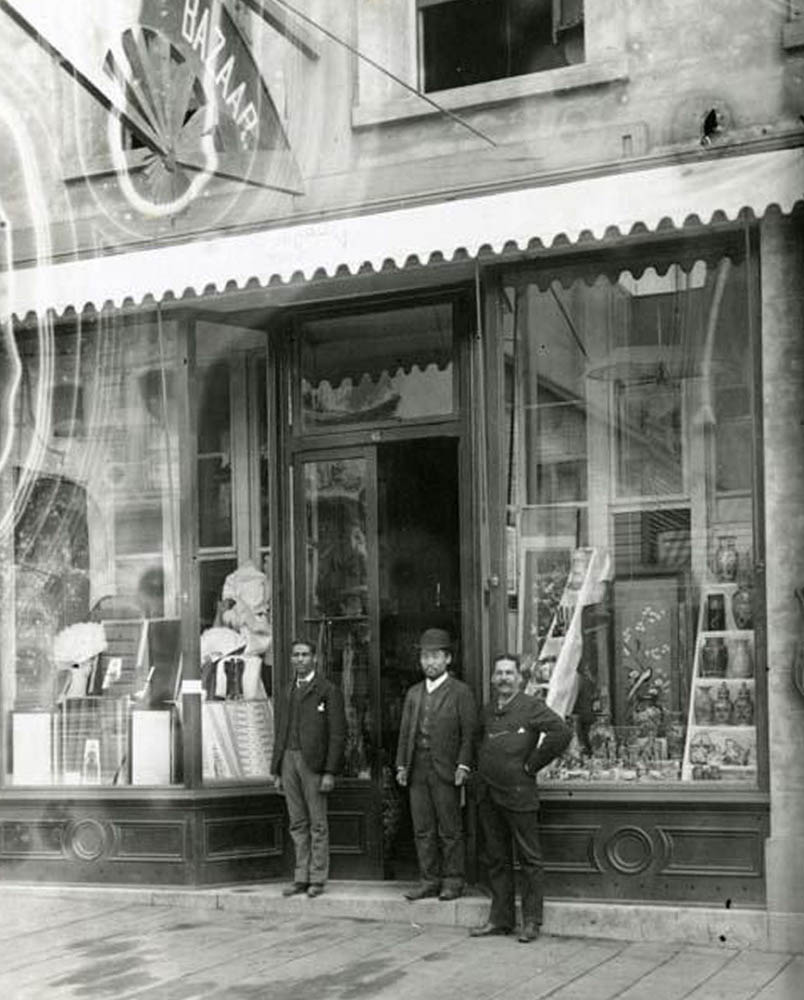

9. The Japanese Legacy

Victoria Archives PR-0033-M00004

1885

This photo of the Japanese Bazaar shows the shop's owner, Charles Gabriel (right) next to one of his most prominent employees, Kisuke Mikuni. The shop, which opened just in time for Christmas 1884, sold wares and curiosities from the Far East, such as hand-painted tea sets, umbrellas, gloves, silk, and jewelry. Gabriel employed and boarded Mikuni and several other Japanese immigrants--Victoria's first. Gabriel and Mikuni met by chance in Yokohama while Gabriel was searching things to sell in his planned shop. He convinced Mikuni to leave his life in Yokohama and come to Canada to work for him.1 The two men enjoyed a close professional relationship, and Gabriel left Mikuni in charge of a mining operation on Tumbo Island that Gabriel invested in.

* * *

Victorians appreciated the culture and aesthetic of Japan, and nowhere is this more apparent than in Victoria's gardens. In 1907, two Japanese-Canadian businessmen partnered with gardener Isaburo Kishida to create a Japanese-style tea garden at the Gorge waterway that was opened to the public. The garden, designed in the traditional Japanese fashion, and with strings of lights that glowed softly after dark, was immediately popular. Kishida's enhanced reputation meant he was commissioned to design Japanese style gardens at Butchart Gardens and, at James Dunsmuir's Hatley Castle (now Royal Roads University).

Sadly the Gorge tea garden garden was forced to shut its doors for good in 1941, when Kishida was interned along with all the other Japanese-Canadians living near BC's coast. You can visit the former site of the the tea garden and learn more about it with On This Spot's Gorge Tour, which can be found in the Esquimalt section.

In the early 20th Century, Britain and Japan were military allies, and as such many Victorians felt close ties with Japan. The city welcomed port calls by vessels from the Imperial Japanese Navy, and when Japan annihilated the Russian Navy at the Battle of Tsushima in 1905, Victoria's newspapers were exultant. Bartenders even apparently served free drinks to Japanese patrons.3

This relationship was however far from perfect: Japanese Canadians were victims of much of the same institutional and casual racism as was inflicted on Chinese Canadians. Victoria resident Asamatsu Murakami wrote in his book, A Dream of Riches, "The white people would say, as soon as a Japanese makes money he goes back to Japan, you're all parasites. But I said I have children here so I'm going to live my life here and I don't look back to Japan."4

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, anti-Japanese hysteria in BC led the government to forcibly inter all Japanese-Canadians living near the Pacific Coast, as a supposed precaution against spies and saboteurs. Sent to squalid camps in the interior, all their property and businesses were expropriated by the government and sold off for pennies on the dollar. The episode is a black stain on Canadian history. The fundamentally racist nature of the internment is revealed by the fact that the ban on Japanese Canadians living near the coast was not lifted until 1949, four years after Japan's unconditional surrender.

After that point none of Victoria's Japanese Canadian residents returned to Victoria. However, their legacy remains in Victoria's gardens, and in the Sakura trees that burst into bloom along Victoria's streets every spring--a reminder of Victoria's once close relationship with Japan.

10. The Fathers of BC

Victoria Archives PR-0014-M07348

1895

The buildings across the Inner Harbour that were once where the Legislature now stands, were known as the 'Birdcages'. Built in 1864, this was where the colonial government administered the colony of Vancouver Island, and then, after British Columbia joined Confederation in 1871, the entire province. They were replaced by the Legislature buildings in the 1890s.

While many men and women contributed to the growth and success of the colony, and later province, two vastly different men have come to be known as the 'Fathers' of British Columbia: James Douglas, a man of mixed-race descent who took a Cree indigenous wife; and Joseph Trutch, a British engineer who came to see the First Nations as subhumans. Both left their stamp on government policy early on, and symbolize two conflicting attitudes of British Columbia's multiculturalism and racial tolerance.

* * *

Douglas was also the man who chose the site of Fort Victoria for the HBC, and governed it as chief factor for the company in the decade to follow. His relatively liberal stance on race relations influenced his policies, and helped stamp early BC with a decidedly racially tolerant outlook.

When the 1858 Gold Rush prompted a mass migration of American miners into what is now British Columbia, James Douglas sought to counterbalance this with increased emigration from those more likely to be loyal to Britain.

At that time San Francisco's black community was threatened by recent supreme court rulings that sought to deny them full citizenship. To Douglas these seemed natural settlers whose loyalty to Britain over America would be all but guaranteed. He promised them land, and full citizenship as British subjects after five years of owning that land, and the full protection of the law during that period.1 As a result, several hundred black families moved to the colony, settling in Victoria, Salt Spring Island, and elsewhere in the colony.

Even before the Gold Rush, Douglas was reaching out to local First Nations to negotiate the sale of land and the rights of the indigenous concerning land use through treaties. However, the legitimacy of these treaties has been long debated as both parties entered the agreement with different ideas as to what was being agreed upon. To Douglas and other colonial authorities, they were agreeing to pay a one-time payment for complete ownership of the land, while the First Nations would keep their traditional village sites, camas fields, and hunting and fishing rights. However, Indigenous oral histories, and the first-hand account recorded in 1934 of Chief David Latass who was present at the signing of the treaties, maintain that the indigenous understood the agreement as a peace treaty. The treaty would allow the settlers to make use of some land for agriculture in exchange for yearly payments.2

Despite the controversial nature of these agreements, and the failure of colonial governments to observe them, the Douglas Treaties were the only such documents in existence for the entirety of Southern British Columbia. Their spirit would be brutally and effectively undermined by the work of BC's first Lieutenant-Governor and the other 'Father of British Columbia': Joseph Trutch.

Born in England in 1826 and raised in Jamaica by his lawyer father, Trutch spent several years as an engineer in the United States before eventually migrating to Victoria, attracted by the economic boom surrounding the Fraser Gold Rush. Trutch's views of indigenous peoples was the polar opposite of Douglas. In a letter sent to his parents after witnessing the active genocide of the indigenous people in Oregon, he had stated the indigenous were "the ugliest and laziest creatures I ever saw, and we should as soon think of being afraid of our dogs as of them."3

In 1864, Trutch's first few acts as the Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works of Victoria reflected his racist attitudes. He emphatically denied the existence of the Douglas treaties, and reduced the size of reserve lands to as much as 10%.4 While Douglas had believed that the First Nations had a role in BC's future and worked to protect their reserve lands from encroachment, Trutch was firmly of the belief that First Nations had no valid claim to the land, and therefore there was little point in negotiating or offering compensation.

He was also the author of Clause 13 of the 1871 Act of Union which brought BC into Canada. It stated in an elusive manner that the federal government would be responsible for pursuing an Indian policy "as Liberal" as the colonial policy of British Columbia. This loose phrasing allowed BC to effectively impose as racist of policies as it liked (which was often), and tied the federal government's hands from preventing the worst excesses. This was to far reaching effects for decades to come.6

After Douglas's retirement and demise shortly after, the early period of positive race relations in Victoria would come to a close. Victoria's First Nations, Blacks, Chinese, Japanese, Germans, and more experienced acts of racism and marginalization throughout the city's history. While Victoria opened its doors and offered opportunity to those of many backgrounds and creeds, the duality represented by Douglas and Trutch illustrate the spectrum of attitudes towards race that have created modern British Columbia.

Endnotes

1. A Perfect Eden'

1. Ted Ross, "Then and Now: Elliot Street." James Bay Beacon, (Feb. 2016), online.

2. Brenda Clark, Nicole Kilburn and, Nick Russell, eds. Victoria Underfoot: Excavating a City's Secrets (Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2008), 15.

3. Michael Layland, "A Perfect Eden": Encounters by Early Explorers of Vancouver Island (Victoria, BC: TouchWood Editions, 2016).

4. Layland.

5. Clark, 21.

2. Fort Victoria

1. Layland, 104.

2. Terry Reksten, "More English than the English": A Very Social History of Victoria (Victoria, BC: Orca Book Publishers, 1986), 8.

3. John S. Lutz, Makuk: A New History of Aboriginal-White Relations (Vancouver BC: UBC Press, 2008), 72.

4. Lutz, 79 - 80.

5. Lutz, 86.

3. The Gold Rush

1. Glen A. Mofford, Aqua Vitae: A History of the Saloons, and Hotel Bars of Victoria, 1851 - 1917, (Victoria, BC: TouchWood Editions, 2016). 1 - 2, 33.

2. Mofford, 33.

3. Mofford, 35.

4. Canada's First Chinatown

1. Layland, 41.

2. Patrick A Dunae, John S. Lutz, Donald J. Lafreniere, Jason A. Gilliland, "Making the Inscrutable, Scrutable: Race and Space in Victoria's Chinatown, 1891," BC Studies; Vancouver, no. 169, (Spring 2011).

3. Clark, Kilburn and Russell, 10.

4. "Vancouver and Victoria Focus: Seeking a New Home," Royal BC Museum (2018), online.

5. The Fraternal Societies

1. Thomas A. Green and Joseph R. Svinth eds. "Shaolin Temple Legends, Chinese Secret Societies, and the Chinese Martial Arts" Martial Arts of the World, An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation, (Vol. 1 and 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CL, 2010), 2.

2. "History," Congregation Emanu-el (2018), online.

6. The Streetcars

1, Henry Ewert, The Story of the B.C. Electric Railway Company, (North Vancouver, BC: Whitecap Books Ltd, 1986), 11.

2. Henry Ewert, Victoria's Streetcar Era, (Victoria, BC: Sono Nis Press, 1992), 13.

3. Ewert, Victoria's Streetcar Era, 28.

4. Ewert, Victoria's Streetcar Era, 33 - 34.

5. Ewert, Victoria's Streetcar Era, 34.

6. Ewert, Victoria's Streetcar Era, 135.

7. The Great War

1.Richard Watts, "1914: Victoria goes to war," Times Colonist, July 27, 2014, online.

2. Robert Ratcliffe Taylor, The Ones Who Have to Pay:The Soldier-Poets of Victoria, BC in the Great War 1914 - 1918, (Oxnard, CA: Trafford Publishing, 2013), 28 - 29.

3. Ted Ross, "Victoria During the Great War," James Bay Beacon, Nov. 2016, online.

4. Taylor, 111 - 112.

8. A Little Bit of Old England'

1. Terry Reksten, "More English than the English": A Very Social History of Victoria (Victoria, BC: Orca Book Publishers, 1986), ix.

2. Taylor, xvii.

3. Reksten, 154 - 155.

9. The Japanese Legacy

1. Gordon and Ann-Lee Switzer, Sakura in Stone: Victoria's Japanese Legacy, (Victoria, BC:Ti-Jean Press, 2015), 27 - 29.

2. Switzer, 8.

3. Switzer, 9.

4. Switzer, inside cover.

10. The Fathers of BC

1, James Douglas, "The Canadian Encyclopedia" (2018), Online.

2. "Lost In Translation: The Douglas Treaties," Times Colonist (February 19, 2017), Online.

3."Joseph Trutch, B.C.'s First Lieutenant-Governor, Left Trail of Controversy," Times Colonist (June 17, 2018), Online.

4. Joseph Trutch, "Times Colonist" (2018), Online.

5. Joseph Trutch, "Times Colonist" (2018), Online.

Bibliography

Clark, B., Kilburn, N. & Russell, N. eds. Victoria Underfoot: Excavating a City's Secrets. Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2008.

Congregation Emanu-el. "History." 2018.

Dunae, P., Lutz, J., Lafreniere, D & Gilliland, J. "Making the Inscrutable, Scrutable: Race and Space in Victoria's Chinatown, 1891." BC Studies; Vancouver, no. 169, Spring 2011.

Ewert, Henry. The Story of the B.C. Electric Railway Company. North Vancouver, BC: Whitecap Books Ltd, 1986.

Ewert, Henry. Victoria's Streetcar Era. Victoria, BC: Sono Nis Press, 1992.

Green, Thomas & Svinth, Joseph eds. "Shaolin Temple Legends, Chinese Secret Societies, and the Chinese Martial Arts." Martial Arts of the World, An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation. Vol. 1 and 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CL, 2010.

Layland, Michael. A Perfect Eden: Encounters by Early Explorers of Vancouver Island. Victoria, BC: TouchWood Editions, 2016.

Lutz, John. "Joseph Trutch, B.C.'s First Lieutenant-Governor, Left Trail of Controversy." Times Colonist. June 17, 2018.

Lutz, John. Makuk: A New History of Aboriginal-White Relations. Vancouver BC: UBC Press, 2008.

Mofford, Glen. Aqua Vitae: A History of the Saloons, and Hotel Bars of Victoria, 1851 - 1917. Victoria, BC: TouchWood Editions, 2016.

Petrescu, Sarah. "Lost In Translation: The Douglas Treaties," Times Colonist. February 19, 2017.

Reksten, Terry. 'More English than the English': A Very Social History of Victoria. Victoria, BC: Orca Book Publishers, 1986.

Ross, Ted. "Then and Now: Elliot Street." James Bay Beacon, Feb. 2016. http://jamesbaybeacon.ca/?q=node/1742

Ross, Ted. "Victoria During the Great War." James Bay Beacon, Nov. 2016.

Royal BC Museum. "Vancouver and Victoria Focus: Seeking a New Home." 2018.

Switzer, Gordon & Switzer, Ann-Lee. Sakura in Stone: Victoria's Japanese Legacy. Victoria, BC: Ti-Jean Press, 2015.

Taylor, Robert. The Ones Who Have to Pay: The Soldier-Poets of Victoria, BC in the Great War 1914 - 1918. Oxnard, CA: Trafford Publishing, 2013.

The Canadian Encyclopedia. "James Douglas." 2018.

Watts, Richard. "1914: Victoria goes to war." Times Colonist. July 27, 2014.