Walking Tour

Skylines

Poetic Reflections on Vancouver

Andrew Farris

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bo P118

Stanley Park has often been described as the soul of Vancouver, a place for people to escape the hustle and bustle of life in a modern city. The Skylines tour is meant to give you a chance to follow the seawall out to Brockton Point, an experience shared with millions who have sought a peaceful place to reflect since the park's founding in 1887. The skyline photographs will let us see Vancouver through their eyes, a city in constant flux. The poems and excerpts allow us to bridge the gulf of time that separates us from those writing a century or more ago, allowing us to hear their thoughts and understand their world.

Few experiences are more profound than the realization that even though we humans may be separated by great chasms of space and time, we are all united in our human experience. No matter how alien to you a person in a grainy ancient photograph may seem, behind those faded eyes were hopes, dreams, and fears.

This tour will help you see how others once experienced this city - the hopes and dreams they held when they first saw its gorgeous skies and the perils they might’ve encountered within. Hopefully, at the end of this tour, you will reflect on your own experiences with our beautiful city.

This project is a partnership with the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association.

1. Boundless Optimism

Vancouver Archives AM1589-: CVA 2 - 144

1902

Vancouver has always been a city blessed with natural beauty and boundless optimism. Both of these shine through in this glowing excerpt from an 1891 booklet published by the Vancouver World called Vancouver City: Its Wonderful History and Future Prospects. As we can see, the reasons we love this city have scarcely changed since the day it was founded; though today we are perhaps slightly less boastful in the way we talk about it (only slightly).

* * *

The location of this city is one of the most beautiful that could be imagined and its surroundings are a source of neverfailing delight to inhabitants and visitors. In this respect no other city of the Pacific coast of North American can compare with it. Gently rising from the south shore of Burrard Inlet on the north side, and from the waters of False Creek on the south, the site presents every feature that is desirable. It enjoys of a foreshore clearly defined and allowing a facility in draining that makes it one of the cleanest and most beautiful cities on the continent. The scenery that surrounds the city is magnificent. Across the harbour towers the grand range of the Cascades. At all seasons these mountains are a beautiful object for the eye to rest upon, especially upon a clear day, when their splendid panorama is fully unrolled to the observer's delighted vision. On the other greater side stretch the calm waters of English Bay and the Gulf of Georgia, with a range of blue hills beyond. On the south and east, Vancouver is shut in by the dark masses of the primeval forests on which the woodman's axe scarce seems to have made itself felt. For picturesque beauty and grandeur, the site of Vancouver is unsurpassed by that of any other city in the world. - Vancouver Daily World, 1891

2. Metropolis of the West

Vancouver Archives AM1376-: CVA 1376-76

1940s

What they called the Metropolis of the West we have come to think of as the Pacific Gateway. When writing in 1926, the famous Canadian poet Bliss Carman found much in his experience of this city that still rings true to today. For him, as for us, Vancouver still seems a city of the future.

* * *

There the adventurous ships come in With spices and silks of the East in hold, And coastwise liners down from the North With cargoes of furs and gold.

Traders up from the coral isles With tales of those lotus-eating lands, And smiling men from the Orient With idols of jade in their hands.

Yellow and red and white and brown, With stories in many an outland tongue, They mingle and jest in her welcoming streets, As they did when Troy was young.

The sceptre passes and glory fades, Only the things of the heart stand sure. Fame and fortune are blown away, Friendship and love endure.

Tyre and Sidon, where are they? Where is the trade of Carthage now? Here is Vancouver on English Bay, With tomorrow’s light on her brow!

- Bliss Carman, 1925

3. Liveable City

Vancouver Archives AM1506-S1-: CVA 447-404

1950

Philip Resnick, a political science professor at UBC, gives us pause to reflect on Vancouver's galling inequality in his poem Liveable City. In this city poverty has always coexisted with immense wealth with disturbing ease.

* * *

- Philip Resnick, 2015

4. The Dead Stoker

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: St Pk P262

1900

James Morton described this scene in a Vancouver bar in 1906.

* * *

His was no fine, heroic end – A biscuit choked his throat – Through feeble frame and weakened heart The cold destroyer smote.

They propped him up against the wall, With mild, unseeing eyes, And face so blue and pinched and small And smile of sad surprise.

Tossed like the driftwood, lost and dead, Upon Earth's farthest shore,. "A stoker from some ship," they said And they knew nothing more.

Yet once he was the darling child Of some fond, loving soul, Who with prophetic eyes and mild Foresaw his shining goal.

But fate had cast him far away A wanderer of the sea Blown aimless as the drifting spray – Toiling and never free.

His days were passed in stokehole grime And sweat from blistering fire That burned up every thought sublime And scorched all high desire.

Yet that fond germ of mother love Prophetic in his soul, Must grow to some new birth above Must cleanse and make him whole.

- James Morton, 1906

5. The Island of Dead Men

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: St Pk P42

1898

The island in front of you is called Deadman's Island, or as the Squamish people call it, the Island of Dead Men. In this excerpt, Pauline Johnson tells us the Squamish legend of how the island got its name as recounted to her by a Squamish man. It's the story of an ancient battle between two tribes for possession of the island. It's a story of great heroism and tragedy, glory and sacrifice. This is a long excerpt, but it is fascinating.

Consider you are standing near the spot where Johnson, one of Canada's most legendary poets, first heard the story. Also consider how many legends about this place have been forgotten, forever lost to time. The First Nations have lived here for at least 10,000 years; Vancouver on the other hand, can claim less than one and a half centuries (1.35% as long at most). Imagine the hundreds of generations that have walked these paths, canoed on these waters, and watched these sunsets. Imagine the stories they could tell us about this place.

* * *

“Always fight over that place. Hundreds of years ago they fight about it; Indian people; they say hundreds of years to come everybody will still fight—never be settled what that place is, who it belong to, who has right to it. No, never settle. Deadman’s Island always mean fight for someone.”

“So the Indians fought amongst themselves about it?” I remarked, seemingly without guile, although my ears tingled for the legend I knew was coming.

“Fought like lynx at close quarters,” he answered. “Fought, killed each other, until the island ran with blood redder than that sunset, and the sea water about it was stained flame color—it was then, my people say, that the scarlet fire-flower was first seen growing along this coast.”

“It is a beautiful color—the fire-flower,” I said.

We crossed to the eastern rail of the bridge, and stood watching the deep shadows that gathered slowly and silently about the island; I have seldom looked upon anything more peaceful.

“Indian people, they call it the ‘Legend of the Island of Dead Men.’”

“There was war everywhere. Fierce tribes from the northern coast, savage tribes from the south all met here and battled and raided, burned and captured, tortured and killed their enemies. The forests smoked with camp fires, the Narrows were choked with war canoes, and the Sagalie Tyee—He who is a man of peace—turned His face away from His Indian children. About this island there was dispute and contention. The medicine men from the North claimed it as their chanting ground. The medicine men from the South laid equal claim to it. Each wanted it as the stronghold of their witchcraft, their magic. Great bands of these medicine men met on the small space, using every sorcery in their power to drive their opponents away. The witch doctors of the North made their camp on the northern rim of the island; those from the South settled along the southern edge, looking towards what is now the great city of Vancouver. Both factions danced, chanted, burned their magic powders, built their magic fires, beat their magic rattles, but neither would give way, yet neither conquered. About them, on the waters, on the mainland, raged the warfare of their respective tribes—the Sagalie Tyee had forgotten His Indian children.

Those from the South returned under cover of night and seized the women and children and the old, enfeebled men in their enemy’s camp, transported them all to the Island of Dead Men, and there held them as captives. Their war canoes circled the island like a fortification, through which drifted the sobs of the imprisoned women, the mutterings of the aged men, the wail of little children.

“Again and again the men of the North assailed that circle of canoes, and again and again were repulsed. The air was thick with poisoned arrows, the water stained with blood. But day by day the circle of southern canoes grew thinner and thinner; the northern arrows were telling and truer of aim. Canoes drifted everywhere, empty, or worse still, manned only by dead men. The pick of the southern warriors had already fallen, when their greatest Tyee mounted a large rock on the eastern shore. Brave and unmindful of a thousand weapons aimed at his heart, he uplifted his hand, palm outward—the signal for conference. Instantly every northern arrow was lowered, and every northern ear listened for his words.

“‘Oh! men of the upper coast,’ he said, ‘you are more numerous than we are; your tribe is larger, your endurance greater. We are growing hungry, we are growing less in numbers. Our captives—your women and children and old men—have lessened, too, our stores of food. If you refuse our terms we will yet fight to the finish. Tomorrow we will kill all our captives before your eyes, for we can feed them no longer, or you can have your wives, your mothers, your fathers, your children, by giving us for each and every one of them one of your best and bravest young warriors, who will consent to suffer death in their stead. Speak! You have your choice.’

“In the northern canoes scores and scores of young warriors leapt to their feet. The air was filled with glad cries, with exultant shouts. The whole world seemed to ring with the voices of those young men who called loudly, with glorious courage:

“‘Take me, but give me back my old father.’

“‘Take me, but spare to my tribe my little sister.’

“‘Take me, but release my wife and boy-baby.’

“So the compact was made. Two hundred heroic, magnificent young men paddled up to the island, broke through the fortifying circle of canoes and stepped ashore. They flaunted their eagle plumes with the spirit and boldness of young gods. Their shoulders were erect, their step was firm, their hearts strong. Into their canoes they crowded the two hundred captives. Once more their women sobbed, their old men muttered, their children wailed, but those young copper-colored gods never flinched, never faltered. Their weak and their feeble were saved. What mattered to them such a little thing as death?

“The released captives were quickly surrounded by their own people, but the flower of their splendid nation was in the hands of their enemies, those valorous young men who thought so little of life that they willingly, gladly laid it down to serve and to save those they loved and cared for. Amongst them were war-tried warriors who had fought fifty battles, and boys not yet full grown, who were drawing a bow string for the first time, but their hearts, their courage, their self-sacrifice were as one.

“Out before a long file of southern warriors they stood. Their chins uplifted, their eyes defiant, their breasts bared. Each leaned forward and laid his weapons at his feet, then stood erect, with empty hands, and laughed forth their challenge to death. A thousand arrows ripped the air, two hundred gallant northern throats flung forth a death cry exultant, triumphant as conquering kings—then two hundred fearless northern hearts ceased to beat.

“But in the morning the southern tribes found the spot where they fell peopled with flaming fire-flowers. Dread terror seized upon them. They abandoned the island, and when night again shrouded them they manned their canoes and noiselessly slipped through the Narrows, turned their bows southward and this coast line knew them no more.”

“What glorious men!” I half whispered as the chief concluded the strange legend.

“Yes, men!” he echoed. “The white people call it Deadman’s Island. That is their way; but we of the Squamish call it The Island of Dead Men.”

The clustering pines and the outlines of the island’s margin were now dusky and indistinct. Peace, peace lay over the waters, and the purple of the summer twilight had turned to grey, but I knew that in the depths of the undergrowth on Deadman’s Island there blossomed a flower of flaming beauty; its colors were veiled in the coming nightfall, but somewhere down in the sanctuary of its petals pulsed the heart’s blood of many and valiant men.

- Pauline Johnson, 1911

6. Lost Lagoon

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-2-: CVA 371-923.1

1898

Lost Lagoon is located behind you, back on the other side of the causeway. This poem by Pauline Johnson is actually how it got its name. Johnson, born of a Mohawk father and an English mother, moved to Vancouver near the end of her life and wrote these poems. Her ashes are scattered in this park, just above Third Beach. There's a memorial there (there's a stop for it in this app).

* * *

It is dark in the Lost Lagoon, And gone are the depths of haunting blue, The grouping gulls, and the old canoe, The singing firs, and the dusk and—you, And gone is the golden moon.

O! lure of the Lost Lagoon— I dream tonight that my paddle blurs The purple shade where the seaweed stirs— I hear the call of the singing firs In the hush of the golden moon.

- Pauline Johnson, 1911

7. Captain Vancouver's Journal

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bo P261

1886

These are the words of Captain George Vancouver on his first sailing into Vancouver's harbour. He was the first European to sail into our wonderful harbour. The way he describes Vancouver all seems so familiar, yet so impossibly distant. Could he have imagined the shimmering forest of glass and steel towers we see today? What would he have made of it all? The island he passes to the north of you is Stanley Park (which was an island at the time) as he travels into the Burrard Inlet before you. The final paragraph describes his journey up Howe Sound, towards Squamish.

* * *

We landed for the night about half a league from the head of the inlet, and about 3 leagues from its entrance. Our Indian visitors remained with us until by signs we gave them to understand we were going to rest, and after receiving some acceptable articles they retired, and by means of the same language, promised an abundant supply of fish the next day. A great desire was manifested by these people to imitate our actions, especially in the firing of a musket, which one of them performed, though with much fear and trembling. They minutely attended to all our transactions, and examined the colour of our skins with infinite curiosity. The general tenor of their behaviour, gave us reason to conclude that we were the first people from a civilized country they had yet seen.

The low fertile shores we had been accustomed to see, though lately with some interruption, here no longer existed; their place was now occupied by the base of the stupendous snowy barrier, thinly wooded, and rising from the sea abruptly to the clouds; from whose frigid summit, the dissolving snow in foaming torrents rushed down the sides and chasms of its rugged surface, exhibiting altogether a sublime, though gloomy spectacle, which animated nature seemed to have deserted. Not a bird, nor living creature was to be seen, and the roaring of the falling cataracts in every direction precluded their being heard, had any been in our neighbourhood.

- Captain George Vancouver, 1792

8. The Sleepy City

Vancouver Archives AM640-S1-: CVA 260-6

1928

Rudyard Kipling was the poet of the British Empire and in his lifetime became the most famous writer in the world. His poems like "The Man Who Would Be King", "The White Man's Burden", and "If-" were known to every schoolchild growing up in the Empire on which the Sun Never Set. He visited Vancouver three times in his life and couldn't help but be caught up in the city's perennial speculative real estate fever, buying several lots. He wrote this description of Vancouver during his first visit in 1889.

* * *

Vancouver possesses an almost perfect harbour. The town is built all around and about the harbour, and young as it is, its streets are better than those of western America. Moreover the old flag waves over some of the buildings, and this is cheering to the soul. The place is full of Englishmen who speak the English tongue correctly and with clearness, avoiding more blasphemy than is necessary.

All that Vancouver wants is a far earthwork fort upon a hill, there are plenty of hills to choose from, a selection of big guns, a couple of regiments of infantry, and later on a big arsenal. It is not seemly to leave unprotected the head-end of a big railway; for though Victoria and Esquimalt, our naval stations on Vancouver Island, are very near, so also is a place called Vladivostok. The people do not know about Russia or military arrangements. They are trying to open trade with Japan in lumber, and are raising fruit, wheat, and sometimes minerals. All of them agree that we do not yet know the resources of British Columbia, and all joyfully bade me note the climate, which was distinctly warm. "We never have killing cold here. It's the most perfect climate in the world.

- Rudyard Kipling, 1889

9. Canadian Born

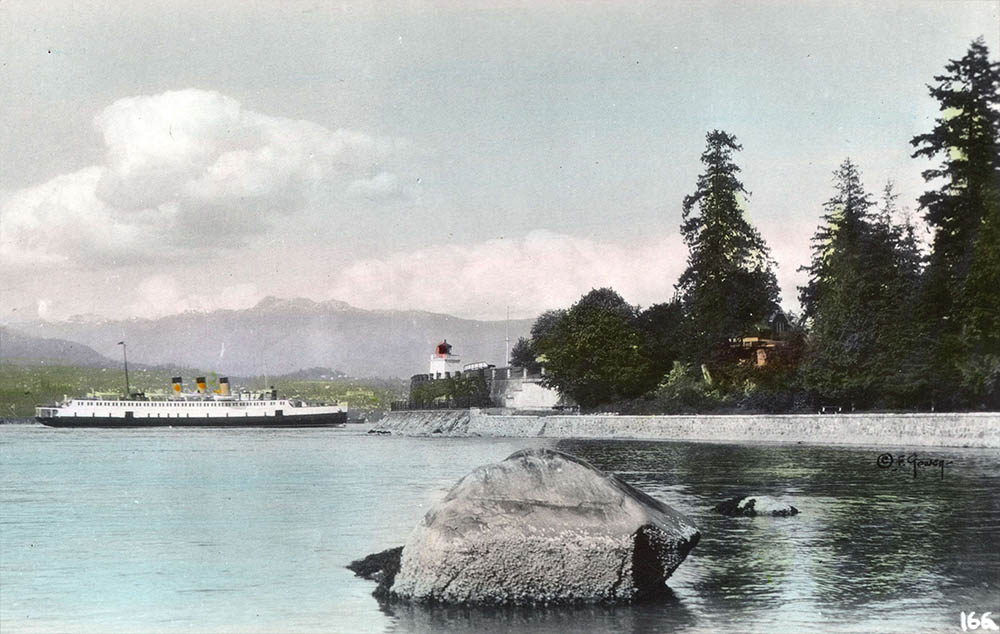

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bo P118

1889

The picture above shows ships in Vancouver's harbour celebrating Dominion Day (Canada Day). The poem below by Pauline Johnson embodies the spirit of the time: bold, optimistic, British. How else can one explain Wilfrid Laurier, the Francophone Prime Minister featured on our five dollar bill, saying "when Britain is at war, Canada is at war. There is no distinction." We forget today, but our concept of Canadianness has evolved dramatically over the past century.

* * *

Few of us have the blood of kings, few are of courtly birth, But few are vagabonds or rogues of doubtful name and worth; And all have one credential that entitles us to brag— That we were born in Canada beneath the British flag.

We've yet to make our money, we've yet to make our fame But we have gold and glory in our clean colonial name; And every man's a millionaire if only he can brag That he was born in Canada beneath the British flag.

No title and no coronet is half so proudly worn As that which we inherited as men Canadian born. We count no man so noble as the one who makes the brag That he was born in Canada beneath the British flag.

The Dutch may have their Holland, the Spaniard have his Spain The Yankee to the south of us must south of us remain; For not a man dare lift a hand against the men who brag That they were born in Canada beneath the British flag.

- Pauline Johnson, 1911

10. Crossing Brooklyn Ferry

Vancouver Archives AM640-S1-: CVA 260-848

1938

This Crossing Brooklyn River was written by Walt Whitman as he watched the Manhattan to Brooklyn ferries in the 1850s, before the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. Though it is not about Vancouver, he speaks to the unity of our experience as human beings in the most profoundly moving way. His poem is transcendent - it is as resonant today as it was over 150 years ago, as a reminder that those in these photos were mothers, fathers, sons, and daughters. One day people will walk this park looking at photos of us, and we will look as distant to them as those that look back at us from these grainy, sepia photographs.

* * *

Just as you feel when you look on the river and sky, so I felt; Just as any of you is one of a living crowd, I was one of a crowd; Just as you are refresh’d by the gladness of the river and the bright flow, I was refresh’d; Just as you stand and lean on the rail, yet hurry with the swift current, I stood, yet was hurried; Just as you look on the numberless masts of ships, and the thick-stem’d pipes of steamboats, I look’d.

I too many and many a time cross’d the river, the sun half an hour high; I too saw the reflection of the summer sky in the water, Had my eyes dazzled by the shimmering track of beams, Look’d at the fine centrifugal spokes of light around the shape of my head in the sun-lit water, Look’d on the haze on the hills southward and southwestward, Look’d on the vapor as it flew in fleeces tinged with violet, Look’d toward the lower bay to notice the arriving ships, Saw their approach, saw aboard those that were near me, Saw the white sails of schooners and sloops—saw the ships at anchor, The sailors at work in the rigging, or out astride the spars, The round masts, the swinging motion of the hulls, the slender serpentine pennants, The large and small steamers in motion, the pilots in their pilot-houses, The white wake left by the passage, the quick tremulous whirl of the wheels, The flags of all nations, the falling of them at sun-set.

- Walt Whitman, 1851

11. Looking to the Future

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: St Pk P124.2

1936

In the case of all these writers (with the exception of Philip Resnick, who is still alive), one wishes it was somehow possible to reach across the great chasm of time, drag them into the present, and show them our city and ask them "What do you think?" One hopes they would not be disappointed. For Alexander Stevens, writing in the 1920s, there is much we will recognize. Much has changed, and yet so little has changed.

* * *

Ninevah, Babylon, Rome - the sound of them is an echo in an empty room, stirring the dust of dead men's bones.

Vancouver - the sound of it is a wave, breaking on the shores of the future.

Tune in. Try to catch the beat of the wave on a distant shore.

Come by day, and rub shoulders with the throng. Be a lone swimmer in the tides that meet and swirl through the streets.

Rise with the sun in Vancouver. Let a Jap bring your hot water, a Chinaman cook your breakfast, a Greek wait on your table, an Italian black your boots, an Irishman hand you a cigar, a Russian sell you a newspaper, a Scotch bobbie tell you the time, a Danish maid clean your room, a Syrian sell you bananas, a Swede give you a shave, a Jew sell you a new tie and some collars, an American ask you for a short cut to a liquor store, an Englishman tell you he owns the show.

Let these things happen and then - ask the nearest policeman to please show you a Canadian.

Rise with the sun in Vancouver. The canyons, between the steel and concrete, lead down to vistas of water shimmering like the wing of a mountain blue-bird. Beyond the tangle of masts and the smoke from the big steamers, rise dark green stairways to the everlasting snows. The grinding clang of the street-cars, the honk of autos, the rumble of trucks are punctuated by the shrill sopranos of ferry whistles, the tenor of tugs, and the throaty bass of ocean liners.

We shall loiter about the wharves, casting an eye to the eternal hills, towards the lions couchant, unchanging against the changing sky, towards Capilano and the singing waters of Melawahna and Tslan Tala.

Let us talk with the ships. Here is a battered tramp, loaded to the waterline with sweet-smelling cedar and fir. The red sun of Japan droops from her stern. In the shadow of Fujiyama, these fragrant timbers will slowly decay to mingle with an alien soil. When the wave breaks, their dust may dream of a gateway and a city by the sea.

Leaning lazily against a pier, reclines an Empress of the Seven Seas. She is breathing softly through her great stacks and ventilators. Soon her heart will pound against her iron ribs When she breasts the long rollers and struggles in the grip of the typhoon.

Oh, we may sit all day on a pier in the sun and ask questions of the ships!

Ships are laden with dreams and memories and old phantoms that whisper through the rigging and creep along their decks after nightfall. But they cannot tell us about the future.

This is Vancouver. This is the Terminal City. This is the Gateway City. Terminal...of what? Gateway...to where?

The day is going. From the mountains, let us look again. A setting sun has flooded the city with crimson, fired western windows with a thousand torches, and silently slipped over the rim of the world.

With the coming of night, Vancouver has donned a garment of stars. Linked and ribboned and looped in a coruscating mantle of jewels, she glitters like the bride of an Oriental king. From her watchtowers she signals fiery messages to sea and sky, to ships in the air and ships below.

Vancouver - crude and magnificent. Vancouver - sordid and beautiful. Vancouver - child and queen, without mind or soul.

Terminal...of what? Gateway...to where?

Vancouver...the sound of a wave, breaking on the shores of the future.

- Alexander Stephen, 1929