Walking Tour

Vancouver's Japanese Canadian Community

The Tragedy of Little Tokyo

Andrew Farris

Vancouver Archives AM1663-: CVA 300-136

For Vancouver's first 50 years, this neighbourhood was home to thousands of Japanese Canadians who immigrated to Canada. They primarily worked at sawmills or on fishing boats, raised families and struggled to gain acceptance in Canada. As a result, this neighbourhood became a small slice of home for the residents located in Vancouver's Downtown East Side.

Then in 1942, this vibrant community disappeared. Businesses were shuttered, homes emptied and the land sold off. Almost overnight, Vancouver's Little Tokyo permanently ceased to exist. All the Nikkei (Canadians of Japanese descent) were rounded up and sent to internment camps in the Rocky Mountains. After the war, virtually none of the Nikkei shipped further inland returned to Vancouver—hardly a surprise after the racism they had encountered. Instead, they spread far and wide throughout Canada.

In this tour we'll chart the rise of Vancouver's Japanese-Canadian community, the lives of the Nikkei, the community they created, and the challenges that they faced. After that, we will see how the entire community suddenly disappeared, exiled to internment camps away from the coast. After the Second World War, they were scattered across the country so that no comparable Japanese Canadian community exists in Canada today.

This project is a partnership with the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association.

1. Japan Opens Its Doors

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Str P245

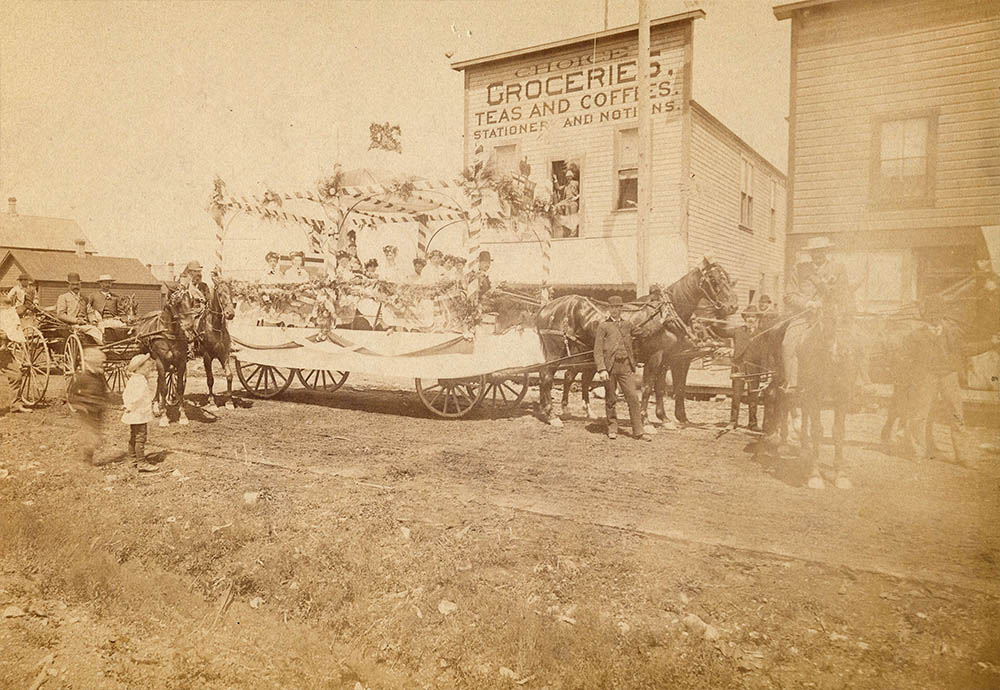

1889

Powell Street is seen in its earliest days before its many Japanese Canadian residents moved in and made their mark on the neighbourhood. It was always a staging area for the Dominion Day (Canada Day) parade; here, people can be seen readying a float for the procession.

* * *

It was not until 1867, the same year Gassy Jack opened his bar in Gastown, a seminal moment in Vancouver's history, that the arrival of an American fleet of 'black ships' (the Japanese name for Western vessels) in Tokyo Harbour spurred a Japanese political revolution. The island nation suddenly flung open its doors to the world, embracing the modern era. Japan was a small, crowded country, poor in natural resources with an overwhelmingly agrarian economy. For many young Japanese men who faced a life of rural drudgery or military conscription, the opportunities that were suddenly available on foreign shores were too good to pass up.

2. Hastings Mill

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Mi P29

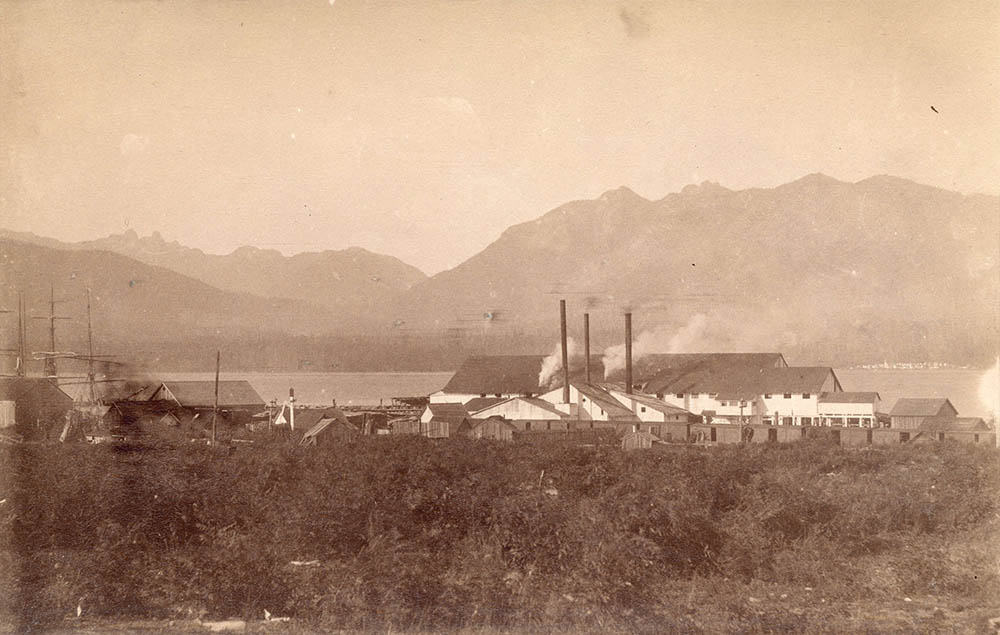

1890

A view of Hastings Mill from Powell and Jackson Streets. The sawmill was the first European settlement in what was to become Vancouver, and many early Japanese immigrants to Canada found work here. They settled in the working class neighbourhood around where you are standing. Japanese-born immigrants to Canada were known as Issei, while their Canadian-born children were Nisei. All Canadians of Japanese descent are called the Nikkei.

* * *

Today, it is hard for us to imagine how difficult life was for these early pioneers. They were paid roughly half as much as their white counterparts, in addition to being given the toughest and most dangerous jobs while working exhausting hours. Unable to speak English, they were frequently exploited by corrupt bureaucrats, bosses and conmen. While many employers were reluctant to take on Issei, the Hastings Mill hired them en masse almost as soon as they'd stepped off the boat. They knew the Japanese Canadians would work 60 hours a week without complaint. Issei millworkers congregated together in this rowdy working class neighbourhood of boarding houses and brothels. By the 1890s, Vancouver's Japanese Canadian community was coming into being.

3. The Methodist Church

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-3-: PAN N143B

1927

The crowds here have gathered for the funeral procession of a prominent member of the Nikkei community. They are standing in front of the Powell Street United Church, which has since been replaced by the Buddhist Church. At the time, this church was a major hub for the Nikkei community. The homes at the right are still standing.

* * *

White Christian missionaries were the exception to the rude welcome. Many churches, such as the Methodist Church, opened their doors to the exhausted and bewildered new arrivals. They effectively became the welcome wagon for the Japanese immigrants, assisting them in navigating Canada's seemingly bizarre social customs, instructing them in the laws, and aiding them in putting down roots in their new country. Some missionaries such as Sister Mary—Omaria-san to the Nikkei—are still remembered fondly today.

Japan did not have a long history of religious strife, and unlike many other Canadian immigrants, no Japanese were fleeing religious persecution. Many were indifferent to religion, so the kindness of the Methodists won them many converts. Today, more Nikkei follow the United Church (the Methodists merged with the United Church in 1925) than any other religion.1

4. The Vancouver Asahi

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-1---: M-3-19.4

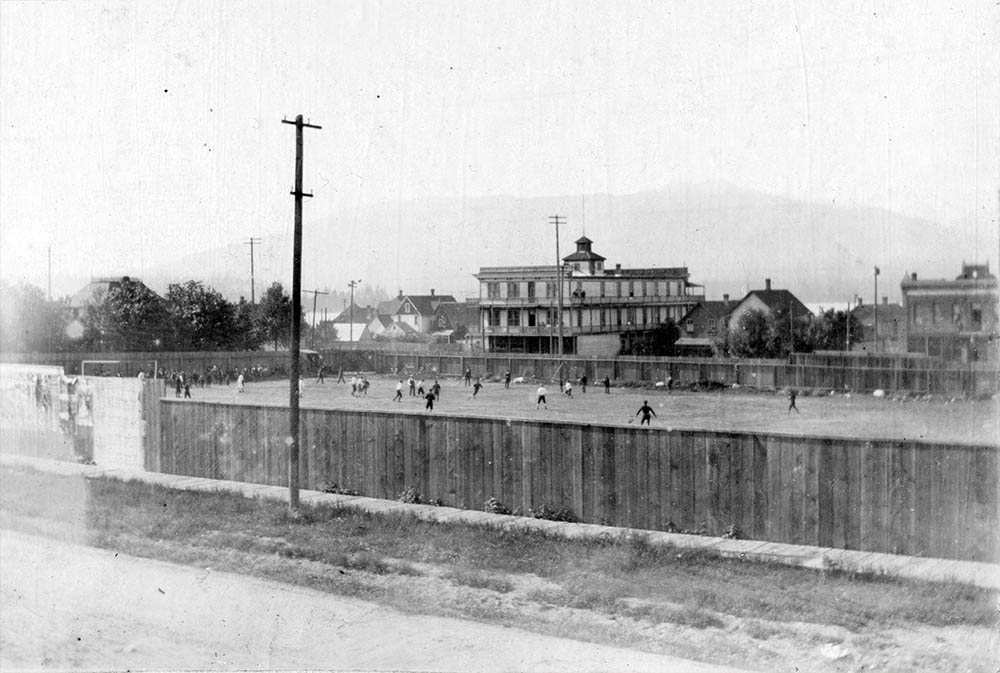

1897

A baseball game on the Powell Street Grounds, today's Oppenheimer Park. Many Nikkei took to baseball like fish to water, and the legendary baseball team, the Asahi, made this park their home field. Renowned for their daredevil baseball style, throughout the late 20s and 30s the Asahis were the most popular baseball team in the province. They were also the subject of a major Japanese movie in 2014.

* * *

Founded in 1914, the all-Nikkei Asahi baseball team initially struggled to make headway against the bigger Caucasian teams. Eventually, they pioneered a bunt-heavy, base-stealing, heart-pounding style of play that the press dubbed "brain ball", which soon captured the imagination of the entire province. At a time when baseball was surging in popularity, the Asahi were determined to act as ambassadors of the Nikkei community. They upheld high standards of sportsmanship and didn't dispute the often racially motivated pronouncements of the umpires. They won their first Pacific Northwest League championship in 1937 and held the title for five years.1

5. The Tairiku Newspaper

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bu N329

1927

This was the headquarters of the Tairiku, the second of eventually four Japanese Canadian newspapers in Vancouver. When the Nikkei were interned in 1942, 70 men hid from the police here before surrendering and being exiled to the interior.

* * *

Kaburagi was on to something, as only a year later, in August 1907, a crowd of 4,000 assembled in front of the city hall at Main and Hastings to listen to speeches from the Asiatic Exclusion League, who aimed to halt "Oriental" immigration to Canada. A speech from a clergyman whipped the crowd into a xenophobic frenzy, and they rampaged through Chinatown, smashing windows and looting stores.

The mob surged into Vancouver's Japanese neighbourhood next, but the Nikkei had advance warning. Armed with clubs and bottles and throwing bricks from rooftops, they successfully defended their neighbourhood from the rioters, whose numbers had swelled to 8,000.1

6. Dealing with Racism

Vancouver Archives AM1535-: CVA 99-2464

1929

A view down Powell Street in the 1920s shows it to be a much busier commercial street than it is today. For Japanese Canadians, this neighbourhood was a place where they could regain a sense of home in a hostile world.

* * *

These myths permeated the politics of the time. Advertisements for the B.C. Liberal party in 1935 read "A vote for the Liberal candidate in your riding is a vote against the Oriental establishment," and "The Liberal Party is opposed to giving Orientals the vote." The Liberals won that election.1

7. A Japanese Canadian Enclave

Vancouver Archives AM1535-: CVA 99-3873

1931

The Fuji Chop Suey restaurant was one of Vancouver's most popular restaurants in the 1930s. A Japanese take on Chinese cuisine, this was but one of the over 500 Japanese Canadian businesses that sprouted up in this nieghbourhood.1

* * *

As Toyo Takata wrote in Nikkei Legacy, there were Japanese Canadian grocers, tobacconists, florists, jewellers, shoe repairers, and barbers. There were rice mills, and factories and manufacturers of soy sauce, tofu and miso paste. There were taxi stands, poolhalls, boarding houses, and bathhouses. There were doctors and dentists, masseurs and midwives. Over 500 Japanese Canadian businesses were crammed into this area.

For the beleaguered Japanese immigrants, the neighbourhood you're now standing in, once cramped and buzzing with activity, had all the sights, sounds and smells of home. In this small slice of Vancouver they could regain a sense of belonging in an otherwise indifferent land. At a population of almost 5,000, Vancouver's Japanese Canadian community was the largest concentration of Nikkei that has ever existed in Canada.2

8. Building Families

Vancouver Archives AM1663-: CVA 300-136

1936

Crowds watch Japanese Canadian women and girls in traditional clothes taking part in a parade down Powell Street. While the first wave of immigrants from Japan were predominantly men, many women soon joined them and had children, creating a well-balanced community.

* * *

9. Proving their Loyalty

Vancouver Archives AM1376-: CVA 1376-227

1939

Two Nikkei cross the street by a lightpost emblazoned with the Union Jack. All the way up to 1942, the Nikkei made strenuous efforts to show their loyalty to Canada and the Empire. It did them little good.

* * *

Japan's entrance into the First World War was met with rapturous applause by the Nikkei. Canadians and Japanese would fight shoulder to shoulder. The Nikkei thought this would prove their worth to the white Canadians and erode their prejudices. They were wrong.

The Japanese Association of Canada asked for volunteers to join the Canadian Army, and 200 immediately answered the call. But when they went to enlist, they were refused. The provincial government feared that if the Nikkei were allowed to fight, they would soon be demanding the right to vote.

Alberta had not institutionalized racism to the extent that B.C. had, and those 200 succeeded in finding a recruiting station on the prairies that would accept them. They went on to fight at Vimy Ridge, Hill 70, and at the Hundred Days, hallowed names in the roll call of Canadian victories. They suffered over 75% casualties, including 54 dead. Today, a cenotaph in Stanley Park marks their sacrifice.1

10. War Comes to Vancouver

Vancouver Archives AM1184-S3-: CVA 1184-1536

1942

The former site of a Japanese Canadian business, boarded up and put up for resale after the occupants had been "evacuated" to internment camps in the interior after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour.

* * *

Many white businesses immediately fired their Japanese Canadian employees without notice. The government immediately sized and auctioned off all Nikkei-owned fishing vessels. Initially, only a few suspected Japanese-born subversives were rounded up by the RCMP. That would soon change.

11. The Dark Days of 1942

Vancouver Archives AM1184-S3-: CVA 1184-1536

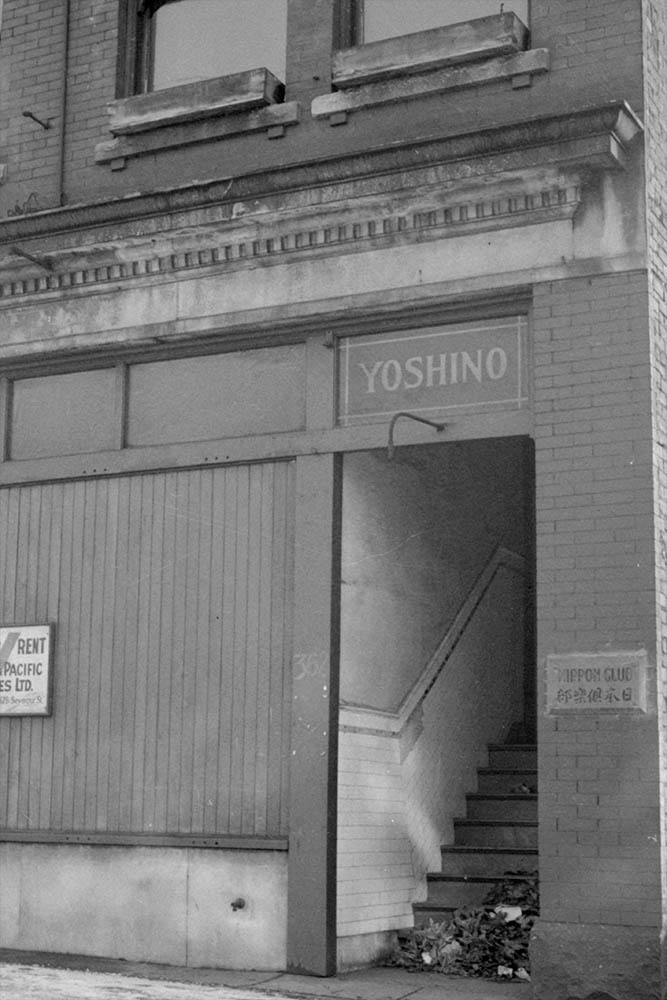

1942

The abandoned Nippon Club, a social gathering place for Japanese Canadians, was shuttered in the spring of 1942. It would be an understatement to say the war against Japan was going badly in the opening months, and fears of a Japanese invasion supported by Nikkei "fifth columnists" rose to a fever pitch.

* * *

In British Columbia, people began to believe an attack was imminent, and their attention turned to the Nikkei. The Member of the Legislative Assembly for Point Grey said the province would become the "meat in a Japanese sandwich, with landing parties in front and 'quisling fifth columnists and enemy aliens in the rear." The Attorney General Gordon Wismer said all Japanese were dangerous, whether they were born in Canada or not, and wanted them removed from the coast.1 What happened next stands as one of the most shameful episodes in this country's history.

12. "Evacuation"

Vancouver Archives AM1535-: CVA 99-2468

1929

The former site of the Japanese Language School, or Nippon Kyoritsu Go-Gakku School. It was shut down in the spring of 1942 when the NIkkei were rounded up and allowed to take one suitcase with them to the internment camps. Everything else—homes, businesses, cars, furniture, clothes—was auctioned off at bargain basement prices.

* * *

Even though the order for internment of all Japanese Canadians made a mockery of the values Canada claimed to be fighting for, he relented and ordered the internment of all the Nikkei. First, the men were rounded up and sent to the Rockies to build railways, then the women and children were sent to desolate camps in the Kootenays, to live in tarpaper shacks in sub-zero temperatures. They were not told that all of their property, their businesses, personal possessions and community buildings—their life's work—was being auctioned off for a fraction its market value.

Sergeant Masumi Mitsui of Port Coquitlam was one of the 200 Nikkei who had fought for Canada in the First World War. He had been awarded the Military Medal for his valour at the Battle of Hill 70 after he retrieved a machine gun from its dead operators and brought it back into action, leading his all-Nikkei platoon to repulse repeated German assaults. 30 of his 35 men were killed in the process.

After the attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941, he wrote the Minister of National Defence on behalf of Japanese Canadian veterans pledging "their unflinching loyalty to Canada as they did in the last war." When the internment orders came, he went to the registration office and flung his medals on the official's desk. "I served my country. You've taken everything from me. What are the good of my medals?"1

He was sent to a camp in Greenwood, British Columbia.2

13. The End of Vancouver's Japanese Canadian Neighbourhood

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-3-: PAN N145A

1927

This is the Japanese Hall and Language School, the centre of community life in the 1930s. It was the only piece of property ever returned to the Nikkei after the war. During the war, the Nikkei were dispersed across the rest of the country and discouraged from ever returning to British Columbia, which they were only legally allowed to do in 1949. It's hardly surprising that few ever did. Vancouver's Japanese Canadian neighbourhood was dead.

* * *

Long after the war ended, the ban on allowing the Nikkei to return to their homes on the coast of British Columbia remained in place. When it was finally lifted in 1949, it's hardly surprising few ever returned. The deeply humiliating experience had been imprinted on the memories of all the Nikkei who once called this place home. Their homes and businesses had new owners. Most ended up sprinkled across the country.

Some scattered places, like the Japanese Hall you are standing in front of, attest to this neighbourhood's rich history. But after the war, most of the resold buildings became dilapidated wrecks. Vancouver's Japanese Canadian neighbourhood died, never to return.

Joy Kogawa was a little girl when she was evacuated to the mountain camps in 1942. Years later, she wrote this poem called "What Do I Remember of the Evacuation."

I remember my father telling Tim and me About the mountains and the train And the excitment of going on a trip. What do I remember of the evacuation? I remember my mother wrapping A blanket around me and my Pretending to fall asleep so she would be happy Although I was so excited I couldn't sleep (I hear there were people herded Into the Hastings Park like cattle. Families were made to move in two hours Abandoning everything, leaving pets And possessions at gun point. I hear families were broken up Men were forced to work. I heard It whispered late at night That there was suffering) and I missed my dolls. What do I remember of the evacuation? I remember Miss Foster and Miss Tucker Who still live in Vancouver And who did what they could And loved the children and who gave me A puzzle to play with on the train. And I remember the mountains and I was Six years old and I swear I saw a giant Gulliver of Gulliver's Travels scanning the horizon And when I told my mother she believed it too And I remember how careful my parents were Not to bruise us with bitterness And I remember the puzzle of Lorraine Life Who said "Don't insult me" when I Proudly wrote my name in Japanese And Tim flew the Union Jack When the war was over but Lorraine And her friends spat on us anyway and I prayed to the God who loves All the children in his sight That I might be white.

- Joy Kogawa

Endnotes

3. The Methodist Church

1. Takata, Toyo. Nikkei Legacy: The Story of Japanese Canadians From Settlement to Today. Toronto: NC Press, 1983.

4. The Vancouver Asahi

1. Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame. "Vancouver Asahi." 28 June 2003. Online.

5. The Tairiku Newspaper

1. Takata, 44.

6. Dealing with Racism

1. Berton, Pierre. Marching As To War: Canada's Turbulent Years, 1899-1953. Toronto: Anchor Canada, 2002, 355.

7. A Japanese Canadian Enclave

1. Vancouver Heritage Foundation. "Historic Map-Guide: Japantown, Vancouver." 2009. Online.

2. Takata, 53.

9. Proving their Loyalty

1. Daubs, Katie. "Walking the Western Front – from war hero to enemy alien and back again." Toronto Star. 12 May 2014. Online.

10. War Comes to Vancouver

1. Berton, 355.

11. The Dark Days of 1942

1. Berton, 343.

12. "Evacuation"

1. Dick, Lyle. "Sergeant Masumi Mitsui and the Japanese Canadian War Memorial." The Canadian Historical Review 91 (3): 435-463.

Bibliography

Bibliography

Berton, Pierre. Marching As To War: Canada's Turbulent Years, 1899-1953. Toronto: Anchor Canada, 2002.

Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame. "Vancouver Asahi." 28 June 2003. Online.

Daubs, Katie. "Walking the Western Front – from war hero to enemy alien and back again." Toronto Star. 12 May 2014.

Dick, Lyle. "Sergeant Masumi Mitsui and the Japanese Canadian War Memorial." The Canadian Historical Review 91 (3): 435-463.

Takata, Toyo. Nikkei Legacy: The Story of Japanese Canadians From Settlement to Today. Toronto: NC Press, 1983.

Vancouver Heritage Foundation. "Historic Map-Guide: Japantown, Vancouver." 2009. Online.