Walking Tour

Stories of Granville Street

The Street at Centre Stage

Alexa Dagan

Vancouver Archives AM1531-: CVA 672-1

From the moment of Vancouver's modern founding in 1886, Granville Street has always held centre stage. For a short time the new city was actually named Granville, after a British politician at the time Lord Leveson, the 2nd Earl Granville. But when the Canadian Pacific Railway's planners decided the tiny logging settlement was going to be the western terminus of their grand nation-building railway, they wanted people in the rest of Canada to be able to find the place on a map. Many people had heard of Vancouver Island, and it was nearby, so the name Vancouver was chosen instead. To avoid hurting the feelings of the the earl for losing his naming rights to the city, the main street connecting the harbour and the highest point in downtown Vancouver was named in his honour.

Granville Street quickly became the city's premier shopping destination, home to upscale boutiques, swanky hotels, and opulent opera houses. It was also headquarters of the city's dynamic nightlife, gaining renown for Theatre Row's legendary vaudeville acts and one of the world's largest displays of neon signs.

In this walking tour we will peel back time to see how Granville Street has evolved over the last 140 years. We will not focus so much on the buildings and businesses themselves, but on the generations of people who have made this city what it is today. As we walk Granville Street, we will learn about the lives and exploits of pioneer lumberjacks and Vaudeville actresses, corrupt politicians and crooked cops, bootleggers and environmental activists. There are so many stories to tell on Granville Street, and this tour will show you just a few of them.

This tour was developed in partnership with the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association.

This project is a partnership with the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association.

1. The Early Days

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Can P25

1887

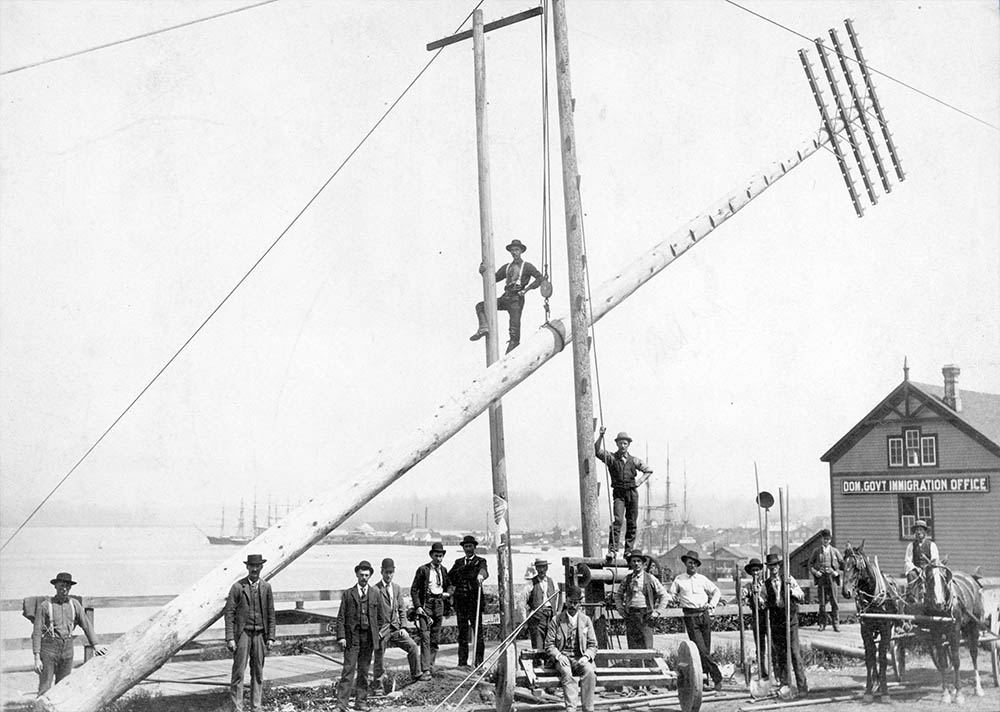

From where you're standing at the foot of Seymour Street, you can get a good view of Vancouver's busy harbour. The iconic Seabus chugs across the inlet, while seaplanes and whale-watching boats zip daringly between hulking freighters filled with the goods that weave Canada into the global economy.

Vancouver's harbour has been filled with ceaseless activity ever since the modern city's founding in 1886. In the background of the historic photo, taken from this spot only a year later, you can see a number of tall ships moored at the wharfs, forerunners to today's massive freighters. What were those ships carrying back then?

The foreground of this photo gives a hint: you can see a team of men using a system of ropes and pulleys to erect a power pole that's easily 20 metres tall; only an average specimen in the coastal forest, where Douglas Fir reached towering heights of 85 metres or more. In the 1880s this land was almost completely blanketed by some of the biggest trees in the world. These giants were the backbone of Vancouver's early economy.

* * *

Finally, in the mid-1860s, two vastly different entrepreneurs saw the potential in the area's seemingly limitless forests and their easy access to the sea. They established rival sawmills on the opposite shores of Burrard Inlet.

Jill Foran, in her book Vancouver's Old-Time Scoundrels, sheds light on these two mills that kickstarted European settlement of Burrard Inlet. The first was established on the north side of the inlet a little to the east of the present site of Lonsdale Quay. From where you're easy it's easy to see across the inlet, the most built-up part of North Vancouver. The settlement that grew up around this mill came to be known as Moodyville, after its American owner Sewell Prescott Moody.

Moody was quiet, principled, and firm with his employees, and took a keen interest in their welfare. Showing some puritan tendencies, he banned alcohol and built churches, a library, and a reading room, rather than a saloon. The community that sprang up around the sawmill could boast a lot of firsts: the region's first school, newspaper, Masonic lodge, and even the first electric lights north of California.

The Hastings Mill run by Moody's rival, Captain Edward Stamp, was very different. Stamp swiftly earned a reputation for bullying, threatening, and exploiting his workers in his relentless quest for profit.

Stamp showed little interest in the wellbeing of his workers and even less in developing the community that grew up around the mill, which was located where Vancouver's railway yards are today, and can be seen in the background of the historic photo above. He did ban drinking on mill property, but didn't care if his employees walked to the edge of the property to imbibe at the many saloons that set up shop there. The first, and most famous of these saloons, was established by the legendary 'Gassy' Jack Deighton, from whom the neighbourhood of Gastown gets its name.

The Hastings Mill attracted almost exclusively young men from a variety of ethnic backgrounds, who--perhaps unsurprisingly--preferred Stamp's 'work hard, play hard' ethos to Moody's puritan austerity. Brawls, stabbings, and conflict fueled by the seemingly endless supply of liquor were commonplace at the little settlement. While the loggers felled and drank, Stamp and the businessmen who followed him lined their pockets.1

These were the humble beginnings of modern Vancouver.

2. Gateway to the Pacific

Vancouver Archives AM1604-: CVA 376-2

1938

In this photo, a horrified crowd watches from the foot of Granville Street as the Canadian Pacific Railway's Pier D burns to the ground in one of Vancouver's most spectacular fires. The Vancouver Sun described the scene: "The advancing fire front and masses of dense smoke forced firemen to rescue hoses and equipment and rush them to safety. The steady roar of the inferno drowned out all other sound, and the vari-colored cloud of thick, oily smoke awed the thousands of spectators massed on every vantage point."1

A small group of firefighters early to the scene beat a hasty retreat into the waters of the harbour when the fire melted through their hose and the heat became unbearable. While no lives were lost in the blaze, the grand hall built on the pier was reduced to ashes.

* * *

His prediction came true in more than one regard. Gassy Jack did not live to see Gastown, as it was first known, live up to its potential--he died in 1875. But nine years later Gastown (renamed Granville, and then Vancouver by railway executives in a far off boardroom) was designated the western terminus for the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), and Canada's new gateway to the Pacific.

Once this decision was made, Vancouver's population exploded almost overnight. The settlement's population was approximately 400 by the time the CPR made its decision, but only 4 years after the railway was built the city numbered well into 13,000.3

The CPR had every intention of capitalizing on every business opportunity that their terminus city presented, and wasted no time expanding into a steamship service that connected Vancouver to the Asia-Pacific. The ill-fated Pier D was the flagship terminal for this service, allowing people to flow into the city from around the world. It served its purpose for 24 years before it burned to the ground.

3. Shopping and Streetcars

Vancouver Archives AM1376-: CVA 189-6

1912

Standing today on the sidewalk of one of Vancouver's busiest streets, the noise is almost impossible to ignore. Pedestrians surge by, chattering away to each other or on their phones, cars and buses roar along the pavement, and on most days there is at least one street musician strumming out a passable rendition of Neil Young's Heart of Gold.

This historic photo vividly depicts the justice to the city's explosive growth and development in the late 1800s; the population almost double between just 1891 and 1901. The photo was taken during a visit by the Duke of Connaught, Canada's governor general, and the excitement of that day is palpable. A great welcome arch has been erected along his parade route, and behind it you can see the old Waterfront Station, decorated with bunting, and just visible a big sign that reads "GOD BLESS OUR MONARCH, ON WHOSE EMPIRE THE SUN NEVER SETS." Vancouver was a very British city back then.

Waterfront Station is where visiting dignitaries first arrived in the city, before proceeding up Granville Street. As the city thrived, businesses bought up space on Granville to cater to the growing population and the street quickly became the number one destination for discerning shoppers. The streetcar lines (you can see the rails running down the street in the photo) were key to connecting Granville with the city's growing suburbs.

* * *

In an era before personal car ownership, streetcars were crucial mass transit for people of all classes. For the cost of a return ticket, families could commute downtown from the expanding suburbs for a day of shopping and diversion. On a typical day, shoppers would start browsing Granville's upscale boutiques , then head down to Hastings and Abbott to the gigantic Woodwards and David Spencers department stores for the daily necessities. In their heyday, streetcars formed the backbone of a cutting edge transit system. They were cheap, efficient, colourful, and--for the most part--safe.

Although Vancouver's 232 streetcars stood at the pinnacle of engineering at the time, one route proved difficult for the car's brake system, much to the dismay of conductor Jack Kelly.

On September 3rd, 1906, North Vancouver finally got a streetcar line, a cause for excitement as this route would connect the ferry terminal at Lonsdale Quay to the rest of the North Shore. However, the new line's got off to an inauspicious start: While returning to the quay down notoriously steep Lonsdale Ave, Kelly was horrified when the car's brakes abruptly failed. The streetcar sailed careened down the hill, violently colliding with another streetcar at the bottom.

While Kelly made it through this first incident unscathed, his streak of misfortune continued three years later when he was at the helm of Car 62. Again, the hill proved too much for the car's brakes. Car 62 faltered and Kelly and his 15 unfortunate, screaming passengers were in for a wild ride as the streetcar flew wildly down the hill, over the dock, and landed with an impressive splash in Burrard Inlet. Kelly, now experienced in street car debacles, jumped from the sinking car, breaking his leg in the process, and abandoning his indignant passengers to their unexpected swim.1

Vancouver's streetcars provided its citizens with reliable and cheap transportation until they were discontinued in 1947. The remaining cars were sent to the scrapyard, or scattered to every corner of the province to start new careers as sheds, barns, and other structures. Car 53, famously now resides in the Old Spaghetti Factory in Gastown where it's a curious centrepiece and nod to Vancouver's streetcar era.

As you walk to the next stop keep your eyes peeled for a playfully colourful alley, now known as Alley-Oop. Alley-Oop is now the site of a city project to meant to reimagine some of the underused and grimy alleys spaces in Vancouver through the use of brilliant colours and interactive activities. These spaces are decorated and designed in a way intended to incorporate an aspect of play and social connection in Vancouver's urban landscape. The Vancouver Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association partnered with HCMA Architecture and Design to develop this experimental project called #MoreAwesomeNow and has become a popular spot for locals and visitors alike.

4. The Home Front

Vancouver Archives AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-3852

1945

Two beaming service members hold up the May 7, 1945 edition of the Vancouver Daily Province with a headline blaring "Vancouver Goes Wild as Germans Surrender". After six long years of war, Vancouverites met the news of VE (Victory in Europe) Day, with riotous celebration. None cheered louder than those with relatives serving abroad.

The Second World War radically affected almost every aspect of life in the city, though unlike hundreds of cities across the world, Vancouver itself was fortunately spared the horror of becoming a battlefield. Hysterical fears of Japanese attack in late 1941 and 1942 led the government to strongly garrison the city, build fortifications, implement rationing and air raid blackouts, and—shamefully—intern the thousands of Japanese Canadians who called Vancouver home.

* * *

According to Peter Moogk's account of Lower Mainland military history, those stationed at the Point Grey Battery (whose concrete bunkers can still be found by intrepid urban explorers) found a particularly entertaining outlet for boredom:

"It was also a favourite trick of the soldiers to flick the [searchlight] beams onto Prospect Point after midnight and, with the aid of binoculars, watch surprised lovers disentangle themselves to escape the all-revealing glare."1

While Canada's West Coast was never really under threat of Japanese invasion, one event, described in an essay by Aaron Chapman in the book Vancouver Confidential, impressed upon Vancouverites the immediacy of the Pacific War.

On the evening of the 20th, the small Vancouver Island community of Estevan Point, just north of Tofino, was settling in for the night. Lighthouse keeper Robert Lally was just lighting the lamp when the Japanese submarine I-26 surfaced just offshore. Lally was still trying to make sense of what he was seeing when a shot from its deck gun exploded in the surf below. Immediately comprehending the situation, he extinguished the light. When the Daily Province reported the incident the next day, Lally was lauded as a hero. At that point in the war, when Allied fortunes were at their lowest ebb, Canada was desperately in need of heroes.

Yokoto Minoru, the sub's commander, in an interview years after the war, remembered the bombardment differently, blaming the sub's failure to hit the community on poor visibility. The lighthouse, illuminated or not, had little impact.

"Because of the dark, our gun crew had difficulty in making our shots effective. At first the shells were way too short, not reaching the shore. I remember very vividly yelling, 'raise the gun! Raise the gun!' to shoot at a higher angle. Then the shells went too far over the little community toward the hilly area. Even out at sea we could hear the pigs in a farmyard near the lighthouse squealing as the shells exploded."2

The was an exceptionally minor incident in the course of the Pacific War, but for nearby Vancouver, already unsettled by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour and the defeat of Canadian troops in Hong Kong, it caused a collective shudder.

By this time, Vancouver was accustomed to the war measures that would seem draconian to Vancouverites today. Rationing of pretty much everything, from gasoline and metal pots, to food and clothing, was now a fact of life. Every citizen, young and old, rich and poor, was issued a ration book and expected to cue patiently at the stores on Granville Street and across the city to receive their weekly allotment.

Air-raid sirens were installed in 1939, and the first city-wide blackout occurred in May 1941, and was commonplace thereafter. Blackouts reduced the city to total darkness, and were meant to deny enemy bombers any light to navigate by. Street lights switched off, windows covered, and drivers even told to paint their headlights blue. For those walking Granville Street at night during a blackout, the effect must have been eerie. One of the few practical effects of these blackouts was an uptick in car accidents.

It was not until the 1980s that the air raid sirens were finally removed, after the City received many complaints about their irritating habit of screaming out during thunderstorms, horrifying Vancouverites afraid of nuclear annihilation during the height of the Cold War.

The black-outs and rationing are now mostly remembered as inconveniences, but there is one tragedy of the war on the home front that was for some much more traumatic. In February 1942, growing fears about Japanese advances across the Pacific combined with racist anti-Japanese to culminate in one of the darkest events in BC's history: the internment of 21,000 Japanese-Canadians. These Canadian citizens, many of whom were born in Canada and fiercely loyal to the Dominion, were rounded up and held briefly at Hasting Park, in the barns at the PNE, before being shipped to squalid camps far from the coast for the duration of the war. A Salt Spring Island resident and internment survivor, Mary Kitigawa, was one of many who sat in on a Vancouver Council meeting in 2013 and shared her experience:

"Going to Hastings Park was one of the most degrading experiences of our lives. The reason I continue to speak about this is because my parents were deeply affected by the internment. Their voices are silent, so I use mine."3

To learn more, try On This Spot's "The Story of Vancouver's Japanese-Canadian Community" tour, which examines the Japanese internment in much greater detail.

5. Perils of a Port City

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Can P67

1892

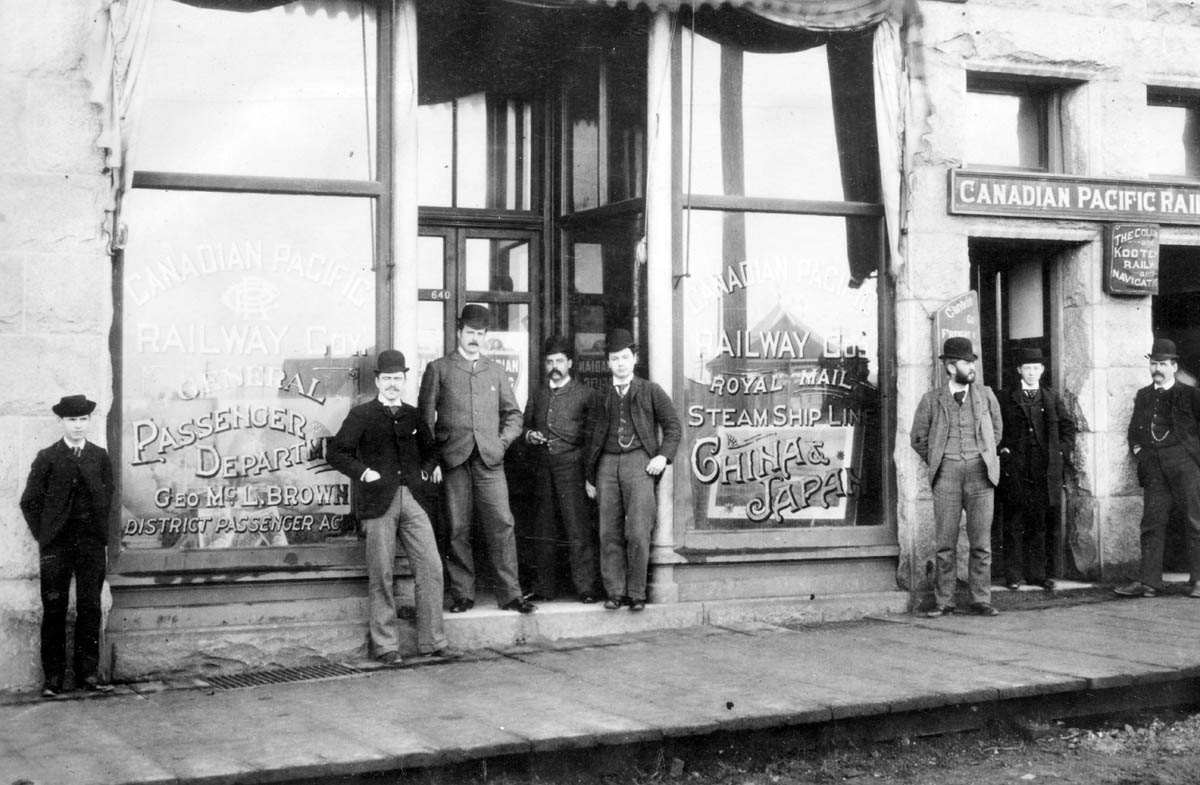

This was the ticket office of the Canadian Pacific Railway's steamship service. The CPR's steamships acted as an extension of the railway, connecting Canada to China, Japan, and beyond--as evidenced by the text on the window.

The investors who funded the CPR saw it as a way to connect the British Empire's disparate parts along an "All-Red Route", named for the red that coloured British possessions on maps at the time. Goods and people sailing from British colonies in Asia like Hong Kong and Singapore could disembark in Vancouver, transfer to a train, cross the country, re-embark on a ship in Halifax, and then sail on to Britain. This made Vancouver a lynchpin of Britain's global trade network, the world's largest at the time.

Vancouver's openness to the outside world meant people and ideas arrived in the city that sometimes didn't conform to stuffy upper-class British sensibilities. This caused tensions that sometimes threatened to boil over.

* * *

Opium wasn't the only illicit substance to pass through Vancouver's harbour: the city also was a significant hub for rum-running during American Prohibition in the 20s. The Gulf Islands and all their many small, private coves provided ideal staging grounds for smugglers sailing down to Washington. For a time their business boomed.

One bootlegger, in an interview years later, wistfully reflected on the experience:

"We operated perfectly legally. We considered ourselves philanthropists! We supplied good liquor to thirsty Americans who were poisoning themselves with rotten moonshine… and brought prosperity back to the harbour of Vancouver."1

6. A Woman's World

Vancouver Archives AM336-S3-3-: CVA 677-615

1900s

Here we can see Granville Street filled with activity, as a woman pushing a stroller peers into the display window at the Hudson's Bay Company store.

Until the early 20th century, Vancouver still had a reputation as a frontier town full of rowdy young bachelors that suffered from a serious shortage of women. While women in the workforce were becoming more common across the country, the frontier of the west was still seen as a man's world, and working women viewed as a curiosity. As women began to settle in Vancouver, many took jobs as laundry workers, waitresses, chambermaids, telephone operators, and retail workers. However one industry in particular was booming and it could be highly lucrative: prostitution.

* * *

"Supposing I were a girl, good-looking, young and full of the joy of life, and I found that by working in a department store I could get only $4 to $10 a week, and that by obliging my outwardly virtuous men friends from time to time I could make from $50 to $200 a week, which should I be likely to do?"1

In a town swarming with unattached men, this economic logic was often inescapable, and many women found themselves drawn into the sex trade. While prostitution was considered a social evil and a criminal offense, the corrupt municipal government and police force that dominated Vancouver during this period was often reluctant to prosecute such a lucrative industry, especially one that so many of the city's elites patronized. How they chose to treat waitresses in Chinatown shows where their true concerns lay, an episode that also showed the growing confidence of women in the workforce.

In the 1930s, at the height of the Depression, some white women supported their families by working as waitresses in restaurants and cafes in Chinatown. While both the women and their employers were happy with the situation, the thought of white women working alongside Chinese men scandalized many members of Vancouver's white upper classes. Anti-asian prejudice combined with Victorian ideals surrounding the sexual purity of white women to fuel hysterical fears of race-mixing and so-called 'white slavery'. The women who worked in Chinatown were often slandered as prostitutes.

Vancouver's Chief of Police, the notorious anti-communist W.W. Foster, acted on the hysteria, leading raids into Chinese businesses, and threatening to revoke their business licenses if they didn't fire their white female employees. Fearing the loss of their livelihoods, the owners unhappily complied. According to Foster, Chinese cafes were "a breeding place for crime and vice, and premises such as these, while they offer employment to white girls who may be in need of work, appear to be little better than a trap for the defilement of young girls."2 It is unclear what--if any--evidence he had to support these allegations.

The women, however, were not having it. On September 24, 1937, 15 waitresses gathered in Chinatown and marched on City Hall to protest the act of taking legitimate jobs away during the Depression. They wrote letters to the Vancouver Sun, defending their jobs and their wrongfully maligned Chinese employers but to no avail.

The waitresses continued the fight over the next two years, but Chief Foster and the mayor refused to budge. According to Rosanne Amosovs Sia, author of the essay "Crime and its Punishments in Chinatown" which records these events, the men who enacted the ban went on to have illustrious careers, while the waitresses disappeared from view, "There is no public acknowledgment of their struggle," she writes.3 The fight was but one of the many half-forgotten struggles waged by Vancouver's women against a system that's historically been stacked against them.

7. Lifestyles of the Elite

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bu P509

1891

You can see here Vancouver's opulent Opera House soon after it's construction. The Opera House was demolished in 1969 to make way for the goliath Pacific Centre, which alone occupies the side of the block, and much of the underground beneath West Georgia and beyond.

Even from its early days, Vancouver was much more than just rough sawmills, grimey saloons, and great fires. The railway and port were bringing the moneyed class into the city, and as with the CPR's Hotel Vancouver (which was located just beside the Opera House facing Georgia Street) and the development of Granville's retail strip, the railway was paying to cater to them.

* * *

Their best was a good one. Vancouver continued its meteoric growth and the Opera House hosted increasingly prominent international talents, such as the world-renowned Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova. The building continued to dominate this section of Granville for 80 years, undergoing a couple ownership changes and one fire before finally being demolished in 1969.

Unlike many other cities, Vancouver's growth did not depend on an agricultural heartland, but was propelled forward by outside capital, much of it coming from the CPR. In exchange for making Vancouver their railway's terminus, they had been gifted most of the land that is modern Vancouver. They wasted no time developing the city as they wished, maximizing profit at every opportunity. Industries proliferated, displacing in a couple years the old growth forests that had stood for centuries.

One of the first plans was to demarcate an east-west division existed in the city. The foreshore of Burrard Inlet and False Creek would be devoted to heavy industry and the east side would serve as worker's housing. The area west of now downtown, the West End, would be a neighbourhood of spacious mansions and English gardens, away from the noxious fumes belched out by the sawmill beehive burners. The CPR was so instrumental in the land development that several city streets and neighborhoods were named after executives and senior staff.

The east was more diverse, with Chinese, Jewish, Italian, Japanese and, Black neighborhoods. However, after around 1907, the majority of Vancouver's wealthiest no longer lived downtown. They had moved on to a new, even more elite gated community on the outskirts of the city: Shaughnessy Heights. Point Grey became another wealthy enclave, building palatial estates on Belmont Avenue, which today is still home to nine of the province's 20 most valuable properties.1

The CPR also set about constructing exclusive golf, tennis and, lawn bowling courts and beautiful park spaces for the newly settled elite but, many would still make their way downtown for other types of entertainment. The Opera House, which hosted all types of performers and entertainment, provided spectacle not only for the upper glass, but for all walks of life.

However, in the early years of the 20th century, the city's elite were rarely above scandal. Corruption wracked the mayor's office and the police force. Many of the upper echelon of society pocketed funds from rum-running and bootlegging, bribing politicians and lawmakers to look the other way. Politicians had mistresses, frequented brothels, and entertained business relationships with crime bosses as the city barrelled into the roaring 20s and beyond.

8. Trouble at City Hall

Vancouver Archives AM1506-S1-: CVA 447-338

1969

In 1971, a couple years after this photo of Granville and Robson was taken, this apartment block was razed to the ground. It was replaced with a mall anchored on an Eaton's department store, then a Sears, and now finally, a Nordstrom.

Before it was the epicentre of Granville's high-end retail establishments, these apartments in the shadow of the Opera House were called the Granville mansions. This building was unexceptional in most regards save that it was home to L.D. Taylor, one of Vancouver's most beloved, corrupt, and sensational politicians.

* * *

Eve Lazarus, in both her book Sensational Vancouver and in an essay in Vancouver Confidential, dedicates extensive research into the man most closely associated with Vancouver's very own Al Capone era: Mayor L.D. Taylor. Taylor was elected to the officer no less than eight times (a record), serving a total of 11 years between 1910 and 1934.

A small, wiry man, Taylor was by all accounts energetic and driven, and frequently seen walking this very street with a cigar in his mouth and sporting his trademark red tie, a reminder of the Liberal politics he espoused. He was a voracious reader, and championed progressive causes; his 1910 platform included giving women the right to vote (which didn't happen in BC until 1916), and supporting the creation of unions.1

Taylor was a man of the people, as his continued victories at the polls demonstrated, but his critics alleged so much corruption that it spawned the Lennie Commission of Inquiry in 1928. Police Commissioner Thomas Fletcher, whose record was just as checkered as Taylor's, claimed that the constabulary often accepted bribes from crime kingpins, while no less than nine officers personally testified they'd been pressured by the mayor to shut down criminal investigations.

The inquiry called into question not only Taylor's role in the city's seedy underbelly, but also the weakness of a police force that allowed itself to be bullied by the mayor, bribed by criminals, and torn apart by factional disputes. The police had failed to keep up with the growth and transformation of the city and were underpaid, understaffed, and still unused to the trappings of modern policing that demanded crimes be prosecuted with evidence and paperwork instead of physical violence.

Detective Sergeant George McLaughlin was investigated four times for accepting bribes. On one occasion he justified it by saying , "these things are coming all the time, If we were getting the money we're supposed to be making, I needn't be working from 9:00 am to midnight and taking abuse for it."2

McLaughlin wasn't the only cop to point out the obvious flaws in the system. VPD officer James Clark Proudlock said "The system under which the police work is to blame and not the police for existing conditions. It is difficult to say whether the police corrupts the city, or the city corrupts the police or the provincial government corrupts both by taxing the city $1 a day for prisoners sent to Oakalla [prison]."3 The prison tax he referred to was blamed for the municipal government's reluctance to see anyone sent to prison.

Although both L.D Taylor and the police department were fully exonerated of all charges, Taylor lost the next election. But, even investigation and defeat couldn't keep Taylor from politics, and he was elected to serve one final term just as the city was veering uncontrollably into the Great Depression.

Even with all of the money he was allegedly raking in from bribes, Mayor Taylor remained in his second-floor walkup in Granville Mansions, while gangsters and other politicians--many of whom were involved in the Lennie Commision--continued to live in actual mansions in Shaughnessy and Point Grey that were conspicuously beyond anything their salaries could afford. G.G. McGreer, the member of the commission most adamant that Taylor be found guilty of corruption, also happened to be the man running against him in the next election, making some wonder if the entire investigation had itself been another manifestation of Vancouver's civic corruption.

Eve Lazarus, as a result of all her impressive research, concluded, "In the end, the Lennie Commission accomplished little. The overall impression of the police force was one of incompetence and corruption, ruled over by a civic administration that was soft on crime."3

9. BC Tries Prohibition

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Str N187

1920s

This historic photo, taken looking north towards the waterfront, is only a little different from what you're looking at today. The sidewalks are wider now, the streetcar rails that carved deep grooves in the asphalt are gone, and glass and steel have replaced some of the terracotta brick facades. But a century later this is still the heart of downtown's entertainment district. Sure, the music pumping out of bars and clubs has taken a completely different turn from the jazz of the 20s, and the fashions of the patrons have evolved, to put it mildly, but one of the biggest departures from 1921, when this photo was probably taken, would be hard to spot in this photo: back then the bars couldn't legally serve alcohol.

While Prohibition, the outlawing of alcohol, is commonly associated with the United States, practically every Canadian province experimented with the idea during the 1920s. BC's flirtation with Prohibition lasted four short years, and caused about as much controversy as banning all alcohol would today.

* * *

The man responsible for counting the ballots was former Premier Richard McBride who was staunchly anti-prohibition. Furthermore those soldiers stationed at home were divided down the middle on the question, so the almost unanimous opposition amongst soldiers overseas raised eyebrows among prohibitionists, and they demanded an investigation. Turns out they were onto something.

It was found that many soldiers had voted more than once, some who voted were actually dead, or in German captivity, and many were not even from BC at all. More than half of these overseas ballots were disqualified, and the referendum result flipped once again and Prohibition was made law. It was now illegal to sell liquor in British Columbia.

The law left loopholes wide enough to drive a beer truck through, and some businessmen knew opportunity when they saw it. Enter Daniel Joseph Kennedy, owner of Regina's Druggists Sundries Company. According to Jason Vanderhill's essay, "The Daniel Joseph Kennedy Story," Kennedy was ready with a lucrative new business model. Under the guise of over-the-counter 'medicine', Kennedy could sell liquor cocktails that slid into legality as medical tonics. Starting with Kennedy's Stomach Bitters, he soon began marketing a whole line of 'medicinal' alcoholic cocktails.

As Prohibition wore on, Kennedy became less subtle and started marketing a series of "Jazz Cocktails," some of which boasted a particularly interesting ingredient. Obtained from a certain bush in South America, this leaf, according to the advertisement, was "stimulating", provided "exhilaration", and "left hunger satisfied." In his article, Vanderhill wryly comments on the identity of the mysterious ingredient. "It would seem Kennedy was experimenting with the coca just as Coca-Cola had done years earlier.."1

Cocktails--cocaine-laced or otherwise--soared in popularity in the speakeasies that sprang up where all the bars had been. The ban did cause a significant decline in the quality of liquor, and cocktails were a tasty and convenient way to cover the flavour of inferior booze. An added bonus was that they could be downed quickly when the drinker was interrupted by a police raid.

BC's Prohibition ended with a particularly embarrassing scandal in 1921. Walter Findlay, the chief official responsible for enforcing Prohibition, turned out to not only have his own liquor warehouse in Yaletown, but was caught smuggling an entire trainload of Ontario Rye into Vancouver. This incident was the proverbial nail in the coffin for Prohibition, which was declared too vulnerable to corruption and difficult to enforce. Officials in America proved much slower to draw this conclusion and Prohibition there lasted 13 whole years.

Once Prohibition ended in BC, Vancouver's booze tycoons found a profitable way to employ their newfound bootlegging skills, by smuggling liquor across the border. As the roaring 20s kicked into full gear, Vancouver's port became a major hub of rum-running activity.

10. The Business of Bootlegging

Vancouver Archives AM1184-S1-: CVA 1184-2298

1946

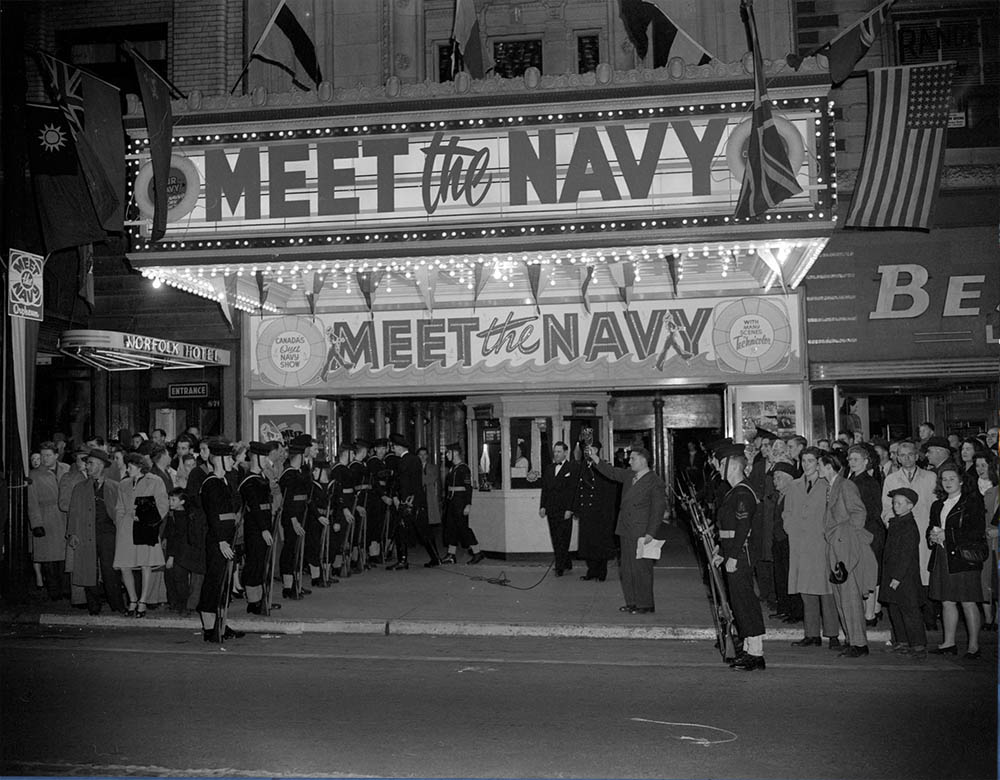

A naval guard stands at attention before an eager crowd of ticket-buyers for the opening night of the film Meet the Navy at the Orpheum. The Orpheum Theatre is one of downtown Vancouver's oldest and most recognizable landmarks, and has long been one of the anchors of Granville Street's famous Theatre Row. Established in 1927, for over 90 years the Orpheum has entertained audiences with rich elegance and class, first as a Vaudeville hall, then a movie theatre, and now a venue for live shows.

The theatre was designed in the Spanish Renaissance style by architect B. Marcus Priteca, who won over Vancouver's king of theatres, Alexander Pantages, with his careful eye for budgeting. "Any damn fool can make a place look like a million dollars by spending a million dollars," he once told Priteca, "but it's not everybody who can do the same thing with half a million." 1 An example of Priteca's canny ability to cut corners is the theatre's opulent ceiling, which in reality is made of plaster and chicken wire and disguises the bland nature of the actual ceiling above.

* * *

In 2011, Billboard Magazine named the Commodore as one of North America's 10 most influentials clubs, and everyone from Katy Perry, to Snoop Dogg, and KISS have played their. However, one detail was left out of the article: the Commodore, along with the Vogue and Studio Theatres on Granville, were all built from the profit the Reifel family made from rum-running to America.

In the wake of America's long-term commitment to Prohibition, enterprising businessmen, fishermen, or anyone with access to a boat scrambled to make a quick buck supplying thirsty Americans with liquor. Rum-running wasn't strictly illegal for Canadians. They simply dropped the liquor off at a prearranged meeting place on one of the local islands and left all the risk of apprehension by the Coast Guard to their American counterparts.

Vancouver bootleggers would officially ship boatloads of liquor to small communities like Bowen Island, then redirect them to the United States. John Snarr, a particularly successful bootlegger pointed out the obvious (but evidently ignored) problem with this loophole: "I'm sure that if the records for that period were examined, places like Bowen Island would show a per capita alcohol consumption that far exceeded human capability!"2.

None benefitted from this trade quite so much as the Reifel family, who banded together with other liquor manufacturers to form the Consolidated Exporters Corporation Limited, which could afford the Canadian government's hugely expensive liquor export licenses.

The Commodore was one of the projects built by the proceeds of the Reifels' rum-running. Perhaps fittingly, the Commodore operated well into the 1970s without obtaining a liquor license. Instead, it operated as a semi-legal "bottle club" where patrons brought in their own liquor and instead paid an astronomical cover charge and fees for ice and mixers once in the club. When raiding the ballroom in search of unlicensed alcohol consumption, police were often forced to crawl underneath tables in search of hastily stashed bottles. Some of the tables had secret compartments for this very reason.3

These days, the Commodore Ballroom is a Vancouver icon. It still hosts a variety of different performers and now has a fully legal liquor license. For a short stretch in the 1990s, the Commodore closed, the result was that, lacking a large enough venue, many bands passed the city by, and local acts lacked a major stage to cut their teeth on. It wasn't long before the importance of the venue was thrown into sharp relief and the Commodore reopened, this time firmly as Vancouver's most legendary venue.

11. Vaudeville's Golden Age

Vancouver Archives COV-S511---: CVA 780-52

1968

As far as iconic Granville institutions go, the Vogue Theatre is one of the most instantly recognizable. The enormous, blazing red and yellow signage is impossible to miss and made even more impressive by the 12 foot statue of the goddess Diana atop it. The theatre is yet another building financed by the bootlegging tycoon Henry Reifel, and another anchor of Granville Street's Theatre Row.

Built in the Art Deco style so popular at the time, the Vogue opened in 1941 to a sold out show of 1,400. The theatre accommodated both live performances and film screenings; its opening night featured the Dal Richards Big Band and a screening of the hockey film I See Ice. As a dual-use theatre for both live shows and films, the Vogue symbolized the shift in entertainment from the wildly popular Vaudeville shows to movies that happened in the 40s and 50s.

Vaudeville was far and away the most popular form of entertainment in Vancouver in the early 20th Century. The fact you can't find a Vaudeville show today--and most people don't even know what it is--says a lot about our changing tastes in entertainment.

* * *

Their popularity continued through the 20s, but the growing popularity of films, and the invention of talking films, was an ominous sign. Many of the theatres built to hold these performances fell on hard times during the Depression. but after those austere years and the Second World War, people thirsted for entertainment and the club men rushed to fill the void.

Returning servicemen in particular were a target audience for the Vaudeville Kings. The State Theatre ran a non-stop procession of comedians, musicians, scantily-clad dancers, and double-film features. The theatre, and others like it, offered exactly the sort of exciting and risque entertainment that newly returned soldiers were seeking and as such, often ran into trouble with the VPD's Vice Squad.

However, this renaissance of Vaudeville was short-lived. By the late 1950s many of these theatres had transitioned fully into film, abandoning Vaudeville altogether. The advent of television was another nail in the coffin, as now entertainment was beamed directly into people's living rooms.

One of Vancouver's local singing legends Mimi Hines, in a conversation with his old friend Sammy Davis Jr., reminisced about the Vaudeville days, saying "Vancouver was the place Vaudeville went to die." Vancouver hadn't killed Vaudeville, but the tradition survived there longer than anywhere else.

Mimi and Sammy, who had become fast friends in Vancouver's showbiz scene, were known for entertaining audiences outside the Mandarin Gardens on Pender Street as they practiced scenes for Sammy's dream of acting in Hollywood. The two would perform mock gunfights and over the top death scenes in the street after the club closed for the night, providing one more act for the amused patrons departing the club.1

As Vancouver left Vaudeville behind, so did the Vogue, one of the last to make the switch to film. In recent years though it has returned to its roots and is now primarily a venue for live performances. While the glamourous dancers, big bands, and comedians characteristic of Vaudeville may be gone, the Vogue's glowing marquee and the goddess Diana continue to harken back to the days when Granville was known as Theatre Row.

12. Falling on Hard Times

Vancouver Archives AM1535-: CVA 99-4520

1934

This photo, taken in the height of the Depression in 1934, shows a crowd assembled in front of the single-screen Dominion Theatre for a night at the movies. Playing then were Tarzan the Fearless and My Woman, apparently popular as the line stretches down the block, despite the economic crisis.

The Dominion Theatre was one of several Granville Street casualties of the changing economics of entertainment. Multi-screen movie theatres made a lot more money than single screen theatres like the Dominion. The better part of Theatre Row was able to survive one entertainment revolution, moving from Vaudeville to film. But next revolution, from single to multi-screen cinema, wasn't possible without tearing down the buildings and starting from scratch.

As we have seen, some theatres like the Vogue and the Commodore Ballroom were able to reinvent themselves, but others weren't as successful. The Dominion switched owners and cycled through a few different names, then stood vacant from 1988 to 1994. Finally the theatre was renovated into the Caprice Nightclub, but that was not to last, and Caprice closed its doors in 2018.

* * *

As early as 1930 city officials were in crisis as the relief demands, already strained by the local unemployed, proved entirely unable to aid the now 10,000 transient unemployed that had settled across the city. Soon so-called 'hobo jungles' sprang up across the East End, in False Creek and on the shores of English Bay and Stanley Park. Photographer W.J. Moore reported on the conditions of these shantytowns:

"A collection of nondescript habitations made out of anything which could be begged, borrowed or stolen, to be hung together some way to afford shelter from the elements to a large number of unemployed men; men from everywhere, all sorts of ages, education, characters, attainments, and which a common want and some misery had banded together in larger or smaller groups for mutual help."1

The jungles quickly became a cause of concern for Vancouver's political elites. Not only was the population of these communities particularly vulnerable to communicable diseases, they were also highly receptive to the efforts of leftist groups to spread anti-capitalist ideology. At the time Canada had virtually no social safety net, and the government in Ottawa under R.B. Bennett steadfastly adhered to a laissez-faire capitalist ideology, where no government intervention in the economy was just the right amount. He blamed joblessness on individual laziness, and wanted to let the Depression run its course, even as the unemployment rate reached 30%.2

By 1935 these tensions had culminated into the Relief Camp Workers Union Strike which engaged in peaceful protest actions, and whose demands were decidedly moderate rather than marxist: a work and wages program, 50 cent a day minimum wage, worker's compensation, unemployment insurance, and suffrage for camp workers. Despite the intentionally uninflammatory nature of these demands, Mayor Gerry McGreer was quick to set out his intention to refuse any and all demands made by the union. After a peaceful demonstration ended in violence, Mayor McGeer read the Riot Act to 1,000 desperate unemployed in Victory Square. The tone was immediately apparent to anyone who listened: that failure to disperse would be met with "not clubs, but bullets."3

Will Woods, in his article, "The Immovable Object," says Vancouverites at the time interpreted the event through their own political bias: "It was either a brave stand against an incipient communist uprising or a heartless spit in the eye of Canada's most needy."4

After the stand-off in Victory Square, Gerry McGeer won a seat as an MP and eventually became a federal senator. His mayoralty was a paradox. While he considered himself sympathetic to the plight of the unemployed and tried to support the poor through large-scale monetary reform, he also threatened violence to those who demanded food and shelter. Vancouver eventually limped through the Depression, rebounding weakly just in time for the Second World War.

13. Flower Power

Vancouver Archives AM1376-: CVA 1376-267

1968

This photo shows hundreds of people marching down Granville Street in an anti-Vietnam War protest. It's a snapshot of the movement that would cement Vancouver's reputation as a haven for long-haired, counter-culture youth. These days, British Columbia has a national reputation for its deep hippie sentiments and commitment to environmentalism. Vancouver especially is known for its addiction to yoga, plant-based diets and, sparkling water, but ask any Vancouverite and they'll tell you, they come by it honestly.

Perhaps no city outside of San Francisco threw itself so wholeheartedly into the "Summer of Love" than Vancouver. During the 1960s, Vancouver was growing past its frontier, logging town roots and became host to a blooming youth culture. Political opinions that condemned the Vietnam War, while celebrating environmental causes, free love, drugs, and rock n' roll were making their way north, and they found an enthusiastic audience in the Vancouver neighbourhood of Kitsilano.

While the government of Canada had no direct involvement in the Vietnam War until 1973 when they sent in Peacekeeping forces, many American draft-dodgers had fled to Canada, and they had a significant effect on Vancouver's culture.

* * *

"I was a weekend hippie," remembers McNamara. "I remember beautiful, hot summers, the smell of pot in the air, lots of long hair, women swirling and twirling in long Afghan dresses, and everybody being stoned out of their minds. People were swarming here, especially from the States, and it made it all so exciting."1

Tanner too, recalls the excitement of the time, "What was really incredible was that it happened so fast. Suddenly by the early spring of 1967, hippies, flower power and free love was everywhere. Vancouver had much more in common with the West Coast USA than with Toronto or Montreal at that time. California was a huge influence."2

However, not all was free love and floral fashions, the centre of the counterculture was also dominated by the political issues of the day, especially the nascent environmental movement. Vancouver, or more specifically Kitsilano, became the headquarters of powerhouse environmental organization Greenpeace, and of legendary activist and internment survivor, David Suzuki.

In 1971, a small group of environmental activists set off from Vancouver in a fishing boat to peacefully protest nuclear weapons testing in Alaska. They named the fishing boat Greenpeace, and within a few short years this small enterprise expanded into a global effort to protect the environment. Perhaps Greenpeace's most memorable mission came about in 1975 when activists embarked in inflatable dinghies to stand between whales and the harpoons of whaling ships.

It was however the combination of politics and marijuana that made the hippies public enemy number one to Major Tom Campbell. According to McNamara, ""He made life hell for the hippies, he was as straight as the hippies were wild, and hated any guy with hair below the earlobe.”3

Mayor Campbell's pro-development views also brought him into conflict with the hippies. He supported the controversial Pacific Centre development, and advocated bulldozing a good portion of the lower East-side to construct a freeway. The climax of this tension resulted in the Gastown Riots of 1971, where the police attacked a peaceful protest in favour of legalizing marijuana. 79 protestors out of 2,000 were arrested and police were accused of charging protestors on horseback and beating protestors with riot batons. In the end the Pacific Centre was built, but the freeway through downtown was stymied by grassroots opposition. Because of this activism Vancouver is the only major city in North America that does not have a freeway running through the centre of it.

Vancouver's "Summer of Love," while short-lived, had lasting effects. Many of the Kitsilano hippies went on to teach at universities, start communes, and retire on the Gulf Islands. Their continued influence has shaped British Columbia's culture, especially regarding environmental issues, progressive politics, and youth culture.

14. Davie Village

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Trans N87.02

1910s

Nowadays, the intersection of Davie and Granville is far too busy to park a car in the middle of an intersection and snap a quick photo, yet, as this photo proves, this was possible sometime in the 1910s. A handful of men hang out of the cab, while a lone figure stands off to the side. Streetcar cables meet in a complicated web above the scene and a horse, still common at this time, crosses the street in the background. In the early 20th century, Davie Street was still a fledgling neighborhood and had yet to develop its identity as one of the country's most vibrant and visible LGBTQ communities.

* * *

"It was a toxic time," says Dutton, "there was a lot of people beaten up, there were a lot of murders. And yet, within that, gay people found safe spaces below the radar - whether it was an illegal boozecan or a houseparty - places where they could be themselves with one another before it became visible. And that was the lifesaver for most people of that generation. Much of that happened in the West End because you could have an apartment party and nobody was going to blink an eye or notice that there's an awful lot of men there and not many women."1

Taking their lead from Britain, Canada decriminalized homosexuality in 1969, an act which would remain illegal in the United States up until 2003. The decriminalization of homosexuality opened the door for the LGBT community to celebrate their identity. In 1971, a historic act took place, one that would remain a celebrated part of the city's culture today, and continues to expand every year. The Gay Alliance Towards Equality organization performed their first demonstration in front of the Vancouver courthouse.

A few years later, in 1978, the forerunner of the Pride Parade took place, as participants marched from the Nelson Park festival site down Thurlow Park to Sunset Beach. Finally, in 1981, the Pride Society was incorporated and the Pride festival was fully organized. That same year, Vancouver Mayor Mike Harcourt declared August 1st to be the start of Gay Unity Week. Since then, Davie Street's LGBTQ community has grown in size and confidence.

Now, much of Davie is LGBTQ-owned and or at the very least friendly to the community, and the nightlife is loud, proud and, exciting. Nowadays, steps are being taken to emphasize the area as more than a street, but as a community. Revitalization and beautification projects are underway to increase Davie Street's status as a queer destination, not just during Pride week, but year round.

Pride parades are now commonplace in Canada, taking place in cities across the country. In a historical appearance, in 2017 Prime Minister Justin Trudeau became the first PM to march in a Pride Parade, joining thousands of participants on the streets of Toronto.

15. The Yale

Vancouver Archives AM1184-S3-: CVA 1184-624

1944

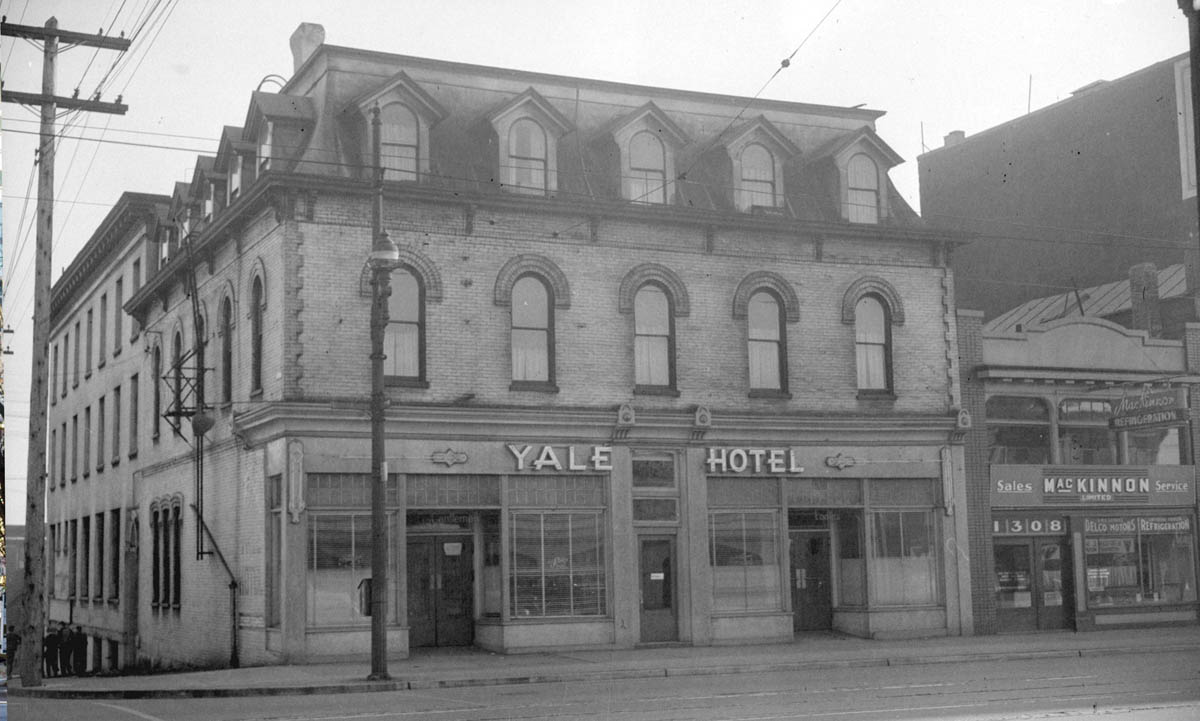

The Yale Saloon is another of Vancouver's iconic nightlife venues that proves that as much as things change, they remain the same. The Yale opened in the 1880s as the Yale Hotel, and mostly served as a bunkhouse for workers at the nearby CPR yards in Yaletown. By 1944, when this photo was taken, The Yale had become a community watering hole, a role it would fill until the mid 1980s when it became one of Canada's best blues venues. In the following years many legendary blues acts played the Yale, including Jimmy Page, Eddy Clearwater, Jimmy Rogers, and Koko Taylor. The neon blue saxophone on the buildings front is a relic from this era. Blues can still be heard at the Yale, though it's partly diversified into a country bar, complete with a cowhide rug and mechanical bull.

* * *

Over the years, Granville's nightlife has shifted from Vaudeville to film, Opera to rock n' roll, and saloon to club, but it's status as the epicentre of Vancouver's entertainment district remains unchallenged. Granville is Vancouver's beating heart and although it will continue to adapt to change as time goes on, the glowing neon lights of theatre row will never truly fade.

Endnotes

1. The Early Days

1. Jill Foran, Vancouver's Old-Time Scoundrels: Gassy Jack's Exploits and Other Skullduggery (Canmore: Altitude Publishing Canada Ltd, 2003), 105.

2. Gateway to the Pacific

1. John Mackie, "This Week in History: 1938 - CP Rail Pier Fire," Vancouver Sun, July 24, 2015. Online.

2. Foran, 105.

3. Foran, 107.

4. The Home Front

1. Aaron Chapman, "City of Fear," in Vancouver Confidential, eds. John Belshaw (Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014), 191.

2. Chapman, 197.

3. Chapman, 201.

5. Perils of a Port City

1. Rick James, Don't Never Tell Nobody Nothin' No How (Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2018), 23.

6. A Woman's World

1. Eve Lazarus, Sensational Vancouver (Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014), 24.

2. Rosanne Amosovs Sia, "Crime and its Punishments in Chinatown," in Vancouver Confidential, eds John Belshaw (Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014), 136.

3. Sia, 139.

7. Lifestyles of the Elite

1.Jeff Lee, "Welcome to Belmont Avenue, home to nine of BC's most valuable properties, Vancouver Sun, Jan. 4, 2013. Online.

8. Trouble at City Hall

1. Mary Rawson, "L.D. Taylor: The Man Who Made Vancouver," The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 75(1): 217-245, January 2016. Online. 2. Eve Lazarus, "L.D. Taylor and the Lennie Commision," in Vancouver Confidential, eds John Belshaw (Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014), 99.

2. Lazarus, "L.D. Taylor and the Lennie Commision," 101.

3. Lazarus, "L.D. Taylor and the Lennie Commision," 103.

9. BC Tries Prohibition

1. Jason Vanderhill, "The Daniel Joseph Kennedy Story," in Vancouver Confidential, eds John Belshaw (Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014), 47.

10. The Business of Bootlegging

1. Eve Lazarus, Sensational Vancouver, 89.

2. Rick James, Don't Tell Nobody Nothin' No How, 21.

3. Eve Lazarus, Sensational Vancouver, 62.

11. Vaudeville's Golden Age

1. Tom Carter, "Nightclub Czars of Vancouver and the Death of Vaudeville," in Vancouver Confidential, eds John Belshaw (Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014), 28.\

12. Falling on Hard Times

1. Stevie Wilson, "Where Men Live on Hope: Vancouver's Hobo Jungles of 1931," in Vancouver Confidential, eds John Belshaw (Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014), 110.

2. Will Woods, "The Immovable Object," in Vancouver Confidential, eds John Belshaw (Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014), 186.

3. Woods, 175.

13. Flower Power

1. Grant Lawrence, "Positively 4th Avenue: the rise and fall of Canada's hippie mecca," Vancouver Courier Oct. 19, 2016. Online. https://www.vancourier.com/news/positively-4th-avenue-the-rise-and-fall-of-canada-s-hippie-mecca-1.2368955

2. Lawrence, Vancouver Courier.

3. Lawrence, Vancouver Courier.

14. Davie Village

1. Vancouver Heritage Foundation, "Davie Street Village." Online.

Bibliography

Carter, Tom. "Nightclub Czars of Vancouver and the Death of Vaudeville," in Vancouver Confidential, eds John Belshaw. Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014.

Chapman, Aaron. "City of Fear," in Vancouver Confidential, eds. John Belshaw Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014.

Foran, Jill. Vancouver's Old-Time Scoundrels: Gassy Jack's Exploits and Other Skullduggery. Canmore: Altitude Publishing Canada Ltd, 2003.

James, Rick. Don't Never Tell Nobody Nothin' No How. Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2018.

Lawrence, Grant. "Positively 4th Avenue: the rise and fall of Canada's hippie mecca," Vancouver Courier Oct. 19, 2016. https://www.vancourier.com/news/positively-4th-avenue-the-rise-and-fall-of-canada-s-hippie-mecca-1.2368955

Lazarus, Eve. "Bring Back the Streetcar!" Eve Lazarus, Writer and Author, April 29, 2017. https://evelazarus.com/bring-back-the-streetcar/

Lazarus, Eve. "L.D. Taylor and the Lennie Commision," in Vancouver Confidential, eds John Belshaw. Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014.

Lazarus, Eve. Sensational Vancouver Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014.

Lee, Jeff. "Welcome to Belmont Avenue, home to nine of BC's most valuable properties, Vancouver Sun, Jan. 4, 2013. https://www.vancouversun.com/news/Welcome+Belmont+Avenue+home+nine+most+valuable+properties/7773145/story.html

Mackie, John. "This Week in History: 1938 - CP Rail Pier Fire," Vancouver Sun, July 24, 2015. https://www.vancouversun.com/news/This+Week+History+1938+Rail+Pier+fire/11240664/story.html

Rawson, Mary. "L.D. Taylor: The Man Who Made Vancouver." The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 75(1): 217-245, January 2016. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/ajes.12131

Sia, Rosanne Amosovs. "Crime and its Punishments in Chinatown," in Vancouver Confidential, eds John Belshaw. Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014.

Vancouver Heritage Foundation, "Davie Street Village." Accessed April 2019. https://www.vancouverheritagefoundation.org/place-that-matters/davie-street-village/

Vanderhill, Jason. "The Daniel Joseph Kennedy Story," in Vancouver Confidential, eds John Belshaw (Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014), 47.

Wilson, Stevie. "Where Men Live on Hope: Vancouver's Hobo Jungles of 1931," in Vancouver Confidential, eds John Belshaw. Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014.

Woods, Will. "The Immovable Object," in Vancouver Confidential, eds John Belshaw. Vancouver, BC: Anvil Press, 2014.