Walking Tour

Chinatown

Resilience in the Face of Adversity

Andrew Farris

Vancouver Archives AM1663-: CVA 300-103

Since Vancouver’s first days the Chinese have been here, forming an integral part of our society. Today we cherish this part of the city’s vibrant identity and find it difficult to conceive of a Vancouver without its Chinese influence, yet this was not always so. Chinatown exists today because of the struggles of thousands of immigrants who strove to make decent lives for themselves in an unwelcoming land.

This project is a partnership with the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association.

1. The Chinese-Canadian Experience

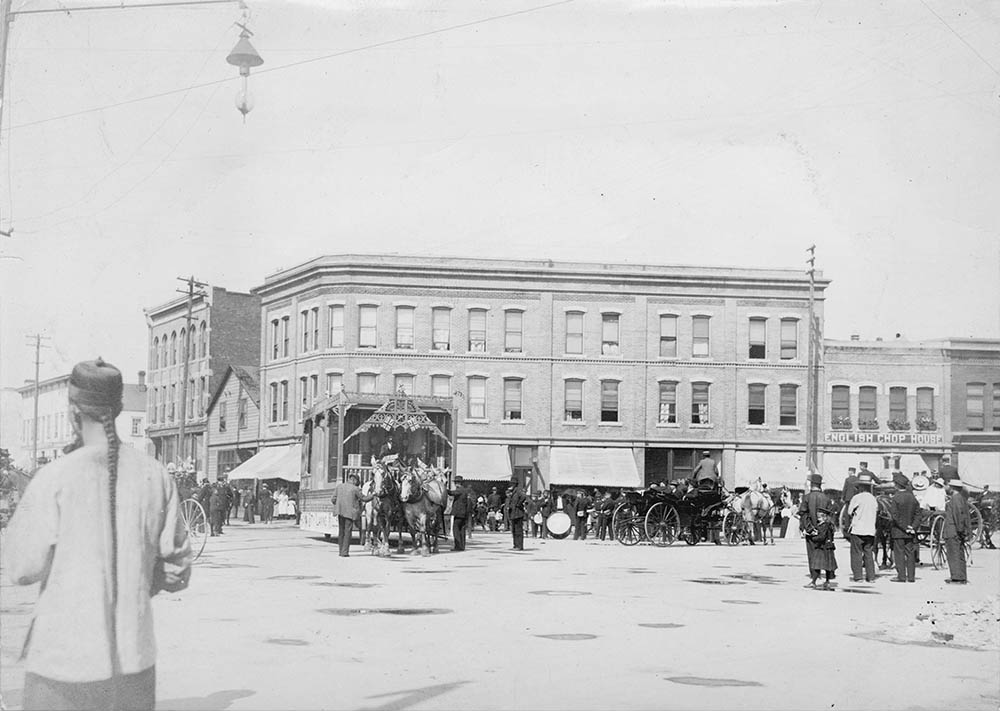

Vancouver Archives AM336-S3-2-: CVA 677-27

1899

A carriage has been turned into a parade float to celebrate an imperial holiday. The Chinese and Europeans immigrants mingling here on the street are indicative of just how closely the two immigrant communities lived together in Vancouver's early years. Nevertheless, Chinese immigrants still had to deal with a shocking amount of racism in their day-to-day lives.

* * *

2. Chinese Pioneers

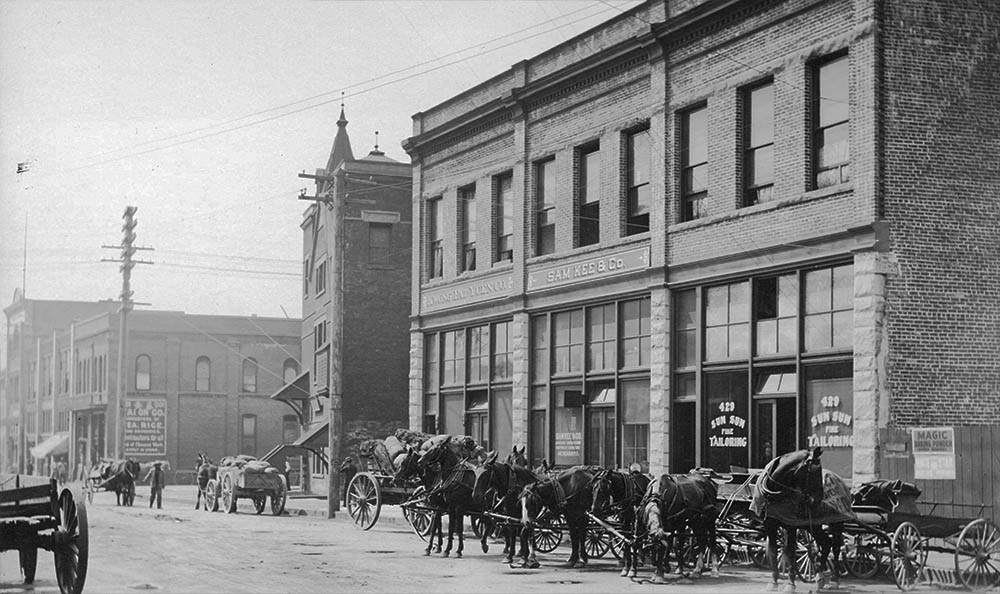

Vancouver Archives AM336-S3-3-: CVA 677-522

1900s

Business carts are lined up outside an old building at the heart of early Chinatown. Located at the fringe of early Vancouver on undesirable land, Chinese residents congregated on the few blocks around here. Many Chinese worked on the Canadian Pacific Railway and when it was completed in 1887 many settled here.

* * *

In this period almost all Chinese immigrants were men seeking work. They first came to seek fortunes in the Cariboo Gold Rush in 1858, and many who followed found work in coal mines, sawmills and canneries. Most significant were the 17,000 Chinese who came to work on the Canada-Pacific Railway. They toiled on the stretch through the Fraser Canyon, the toughest stretch in all Canada. They worked in appalling conditions and received only half the pay of white workers. They were invariably given the most dangerous tasks, like handling unstable explosives to blast a way through the mountain. It is thought over 600 were killed, four for every mile.1 The number is probably higher since in this epic nation-building endeavour the authorities did not count the Chinese dead—only the white. After the railway was completed many came to settle here.

3. Coming to Canada

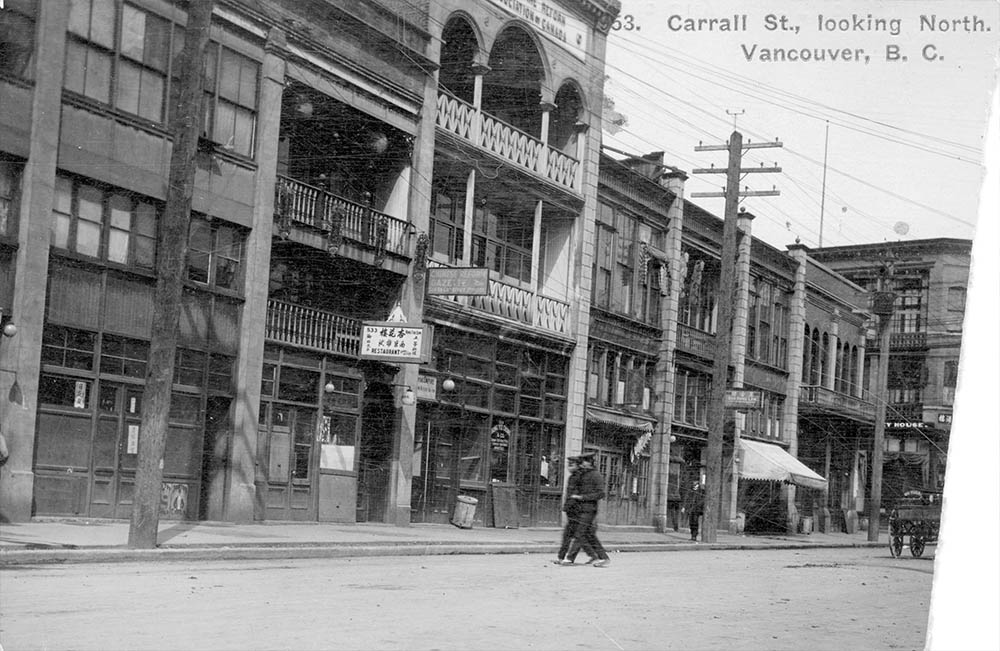

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-2-: CVA 371-2116

1910

People congregate on the street near the Chinese Freemasons Building at left. The thousands of Chinese who arrived in the late 1800s and early 1900s were fleeing a hideous cocktail of strife, war, disease and hunger that convulsed China in this period. Most of these men came from Canton, a region whose spiraling population was overshooting the land's ability to feed them.

* * *

There are almost too many factors to name. China in the late 1800s was teetering on the brink. The Qing Dynasty that had ruled China since the 17th Century was collapsing. A series of civil wars caused misery, dislocation, hunger, and banditry on an almost unimaginable scale, quickening the empire's disintegration. Just one of these wars, the 1850s Taiping Rebellion, may have killed more people than World War II.1 Foreign powers like Great Britain, Russia, France and Japan smelled blood and descended on the weakened empire. A series of short, sharp wars that invariably resulted in Chinese defeat further discredited the Qing and shrank their territory.

What's more, the population was growing rapidly, stretching already scarce agricultural land to the limit. In Canton, where most of the immigrants to Canada came from, an estimated 600 people lived in every square kilometre.2 The rural peasants who comprised the vast majority of the population faced a crushing tax burden, sometimes as much as half their meagre harvest. It only took one bad harvest to leave a farmer under a mountain of debt.

It's hardly surprising then that many Chinese took the shamelessly advertised promises of vast riches in a faraway land at face value and booked passage for Canada. The lives that awaited them rarely lived up to the hype.

4. Shanghai Alley

Vancouver Archives AM1663-: CVA 300-196.06

1937

A crowd has gathered for a funeral procession down Shanghai Alley. This alley, and adjoining Canton Alley, which no longer exists, was the cultural hub of Chinatown in the early years of the 20th Century. Hard economic times in the 1910s and 1920s caused the decline of this area until most of it was finally demolished. A couple dilapidated buildings are the only evidence of the people that called this formerly bustling and exciting place home.

* * *

The people who lived here came overwhelmingly from a small part of the Canton Delta just north-west of Hong Kong. They were ethnically and culturally distinct from the Han Chinese, speaking a dialect of Cantonese. They brought with them a rich culture that had developed over 5,000 years, though some of aspects of it unnerved Vancouver's white population. One practice in particular, that of burying their dead for seven years before exhuming them and shipping their bones back to China, was the subject of horrified accounts in the white press.

The massive recession that followed the boom times of 1913 hit the Chinese community particularly hard. Many people fell behind on their property taxes and were foreclosed on. Soon the two alleys had decayed and were classed as slums. In the 1940s they were almost entirely demolished. All that remains of this neighbourhood is this short stretch of Shanghai Alley and the street signs.

5. Finding Work

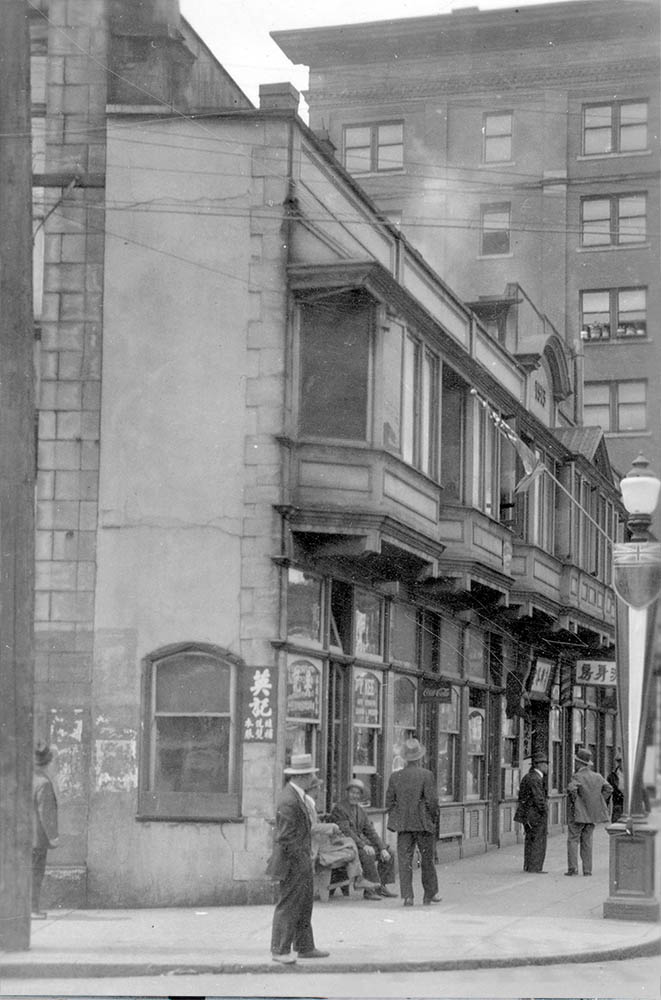

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-2-: CVA 371-1076

1910s

Some of the commercial buildings we see here have the distinctive characteristic of Chinese buildings in Vancouver that you will rarely see elsewhere in the city: recessed upper-floor balconies. The Chinese who came here were widely praised as hard workers, but no minimum wage existed and employers took advantage of this by hiring Chinese workers and paying them peanuts. Unemployed white workers did not take well to this.

* * *

Chinese labourers were usually paid half the wages of their white counterparts. So during many periods of high unemployment, jobless whites were infuriated by the Chinese who they perceived to be stealing their jobs. More than once this led to outbreaks of anti-Chinese unrest. During the Great Depression, Vancouver City Council published lists of Chinese currently with jobs beside lists of whites who were unemployed, cynically deflecting blame for the joblessness of whites onto the Chinese immigrants and stoking racial hatred.2

6. Growing the Community

Vancouver Archives AM1108-S4-: CVA 689-65

1920

A class of Chinese boys is posing for a photo. Everyone looks dressed up for picture day and the three on the left look particularly proud in their scout uniforms. The difficulty in bringing women and children over to Canada from China meant that it took years for a real community to take shape. The Chinese Benevolent Association founded the first Chinese school only in 1900, educating the small but growing number of Canadian-born children.

* * *

In 1871 the first baby was born in Canada to Chinese parents. W.A. Cumyow grew up to open a store at the corner of Cordova and Homer in 1888 that offered real estate, brokerage and translation services to the Chinese community. As more children were born in or immigrated to Canada, a school was needed for them. The Aiguo Xuetang, or Patriotic School was founded in 1900. Most Chinese children went to provincially run non-segregated schools with white students as well.1

In highly conservative Confucian society women were largely confined to traditional gender roles. In these early years Chinese women were rarely seen in Vancouver outside the home. There were exceptions: Canadian-born Susan Yip Sang enrolled at UBC in 1914, making her likely the first Canadian-born Chinese student to attend that institution.2

7. Sam Kee

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bu P255.7

1936

The building here holds a Guinness World Record for the narrowest commercial building in the world. It's named after the man who had it built, the Chinese entrepreneur Sam Kee. To expand Pender Street the government expropriated the bulk of his lot, leaving Sam with only a narrow strip of land. Refusing to sell, he instead had this two metre wide building constructed.

* * *

After stints as a labourer Sam began his business career when he bought a share in the Wah Chong Laundry in Gastown. He quickly expanded the company into a whole range of services, selling groceries and charcoal and contracting out work crews. In the 1890s he founded the company that bears his name and began importing all manner of goods from China, while exporting fish and other goods back the other way. He became a major investor and rented out dozens of buildings across the city so that by 1907 revenue was perhaps as high as $180,000 ($4 million today).1

He spoke practically no English, but his business dealings spanned the Asia-Pacific and he worked with many white firms, earning hard-won respect across the province. He was sometimes subject to official harassment, but he was clever and inventive in working around these obstacles, allowing his business and his community to flourish in adverse circumstances. The supreme evidence of this stands in front of you now, the cheeky, world record-holding response to having his land expropriated.

8. Chinatown Arch

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Arch P9.2

1912

The Chinese community has erected a welcoming arch for the visit of the Duke and Duchess of Connaught. The Duke was the Governor General of Canada at the time. A symbol of Chinese-Canadian loyalty to the Empire, this arch could not mask the official discrimination the Chinese faced in their adopted homeland.

* * *

The province's politicians acted on these fears, passing new discriminatory legislation almost every year. A variety of race-based taxes were passed. Chinese-Canadians were barred from working on city projects, excluded from professions like law and architecture and denied the right to vote.

Most white British Columbians looked at the Japanese immigrants through this same racist lens, seeing both groups as 'Orientals' and 'Asiatics.' The problem was Japan was a rising power and in 1902 signed an alliance with Great Britain (and therefore Canada). The Canadian government awkwardly vetoed the most racist legislation against Japanese immigrants. The Chinese had no such protections. Unlike Japan, China was descending into chaos and her government's protests could be lightly shrugged off.

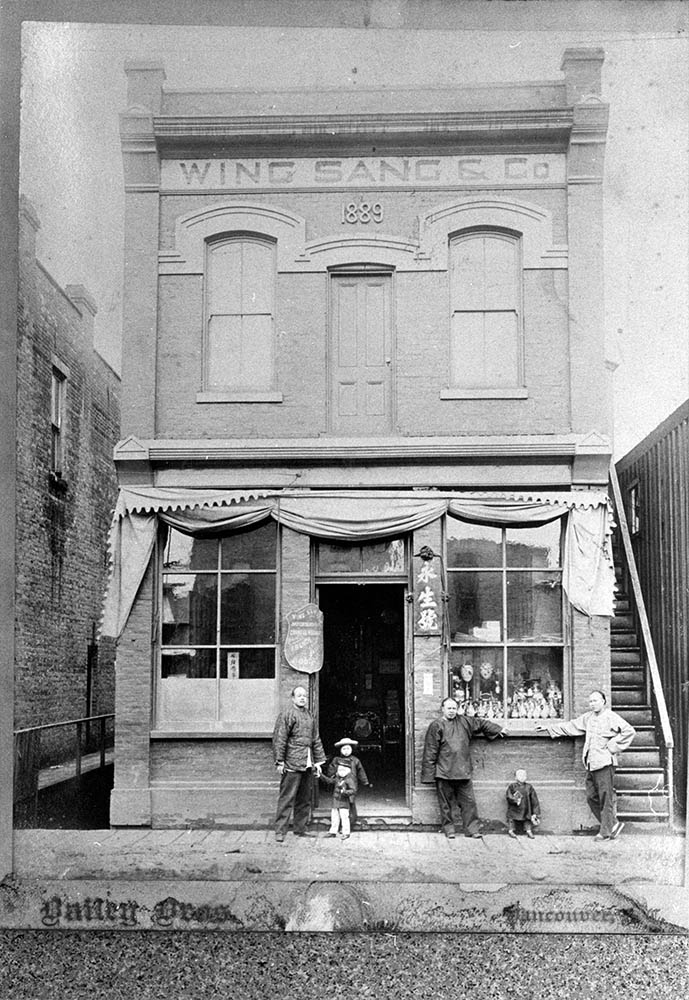

9. Organizing the Community

Vancouver Archives AM1108-S4-: CVA 689-51

1900

Another entrepreneurial businessman, this is Yip Sang in front of his Wing Sang Company building, one of the oldest buildings in Chinatown. A few of his many children are in the picture, and the girl wearing the hat may just be Susan Yip Sang, the first Chinese-Canadian to attend UBC.

* * *

These organizations served a huge range of functions, from schooling, health care and welfare, to promoting business cooperation and lobbying government. Funds raised by the Chinese Benevolent Association built a Chinese hospital and the Patriotic School. When Chinese unemployment shot up to 70% in the 1910s, the CBA disbursed money to the poor.1

The Chinese Empire Reform Association was China's first ever political party and sought a constitutional monarchy in China. In the 1900s Yip was crucial for spreading the association's membership throughout the world's Overseas Chinese communities.

These organizations held the Chinese community together, and allowed them to weather the period of extreme hardship that lasted with few interruptions from the 1900s to the 1940s.

10. The Race Riot of 1907

Vancouver Archives AM1376-: CVA 1376-506

1907

The buildings on the south side of Pender seen here were wooden long after much of the rest of the city had started building in brick. You can see the building at the end of the street that was demolished to make way for the widening of Pender and led to Sam Kee's narrow building. The Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Chinese Garden to your left today was only completed in 1986. The same year this photo was taken an anti-Chinese riot rocked Vancouver leading to the destruction of Chinese property and darkening relations between Vancouver's white and Chinese populations for a long time to come.

* * *

Swelling now to 8,000, the mob rampaged into Chinatown, smashing windows and looting. The Chinese had no warning and fled to the back of their shops and homes as the mob flowed by, leaving no window unbroken. Luckily nobody was killed, though there were apparently two stabbings. Next the mob moved on to Vancouver's Japanese Canadian community, but the Japanese Canadians had advanced warning. They armed themselves with bottles, clubs, and bricks and fended off the mob.1

Respectable Vancouver was embarrassed and the city's preeminent citizens came forward to denounce the riot. Perhaps realizing they'd gone too far, the Asiatic Exclusion League was disbanded five days later. One newspaper blamed the event on a small number of hoodlums and was gravely worried about the about the damage done to the city's coveted reputation, shades of another Vancouver riot 104 years later.2

11. Racist Myths

Vancouver Archives AM640-S1-: CVA 260-1010

1939

A crowd of both Chinese and European-Canadians has gathered to watch a funeral procession. By the late 1930s racial prejudices had begun to soften considerably, but up to that point the Chinese in Canada had to put up with all sorts of casual racism. Vancouver's newspapers were more than happy to spread this bile, helping perpetuate a series of myths that diminished Chinese people.

* * *

A variety of myths about the Chinese were circulated and widely believed, allowing many white people to dehumanize the Chinese in their minds. The Chinese were accused of living in squalor, though Chinatown was located at the edge of the False Creek swamp and not connected to the sewer system for a long time. They were accused of bringing in infectious disease, though a royal commission in 1900 found this to be untrue. They were accused of importing immense quantities of opium, though the drug wasn't illegal in Canada until 1908, and it should be remembered Britain went to war with China several times to force that country to open its doors to opium (The Opium Wars). They were accused of outbreeding European Canadians, even though in 1941 there were only 35,000 Chinese in a provincial population of 817,000.1

In 1921 the Vancouver Sun published The Writing on the Wall, a novel by Hilda Howard. In the novel several members of British Columbia's white elite are blinded by their greed and manipulated by nefarious Orientals bent on provincial domination. The elites close their eyes to unlimited immigration, opium smuggling and the spread of disease. Eventually the Chinese begin poisoning white people's food to kill them off, while the Japanese actually invade. The world of the whites is collapsing when at the end of the novel the protagonist, a white politician, awakens in a cold sweat only to discover it had all been a bad dream. The nightmare, he realizes, was a warning: he must never sign a bill giving Orientals the right to vote.2

12. Latest from the Front

Vancouver Archives AM640-S1-: CVA 260-758

1937

Men read Chinese newspapers tacked up on the wall at the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. This war was somehow an even more catastrophic blow than all the dozens rained down on China over the previous century. For the Chinese in Vancouver the terrible news from their homeland had followed a particularly bad time for the community. In the 1920s and 1930s racist immigration laws threatened to strangle the Chinese community out of existence.

* * *

China's domestic politics was never far from Vancouver and new political parties had set up shop in the city, leading to bitter schisms over the future of China itself. In 1937 however all these differences were cast aside when Imperial Japan invaded China. The Japanese invasion was immediately successful, and incomparably brutal. Chinese Canadians agonized over newspaper stories about the bombing of Shanghai, the rape of Nanking, and the fall of Peking (Beijing).

13. Aiding the War Effort

Vancouver Archives AM1663-: CVA 300-103

1938

Acrobats perform in a parade at the opening of the Chinese Carnival. The happy atmosphere masks the underlying uncertainty for the Chinese community at this time, as the war was going very badly indeed for China. The Chinese in Canada mobilized to send whatever aid they could to the ailing mother country.

* * *

14. An Early Political Meeting

Vancouver Archives AM1376-: CVA 1376-355

1900

An early meeting of Chinese Nationalists to discuss Canadian politics and events in China. Vancouver became host to a series of political parties seeking change in China, and many prominent Chinese reformers, intellectuals and politicians stopped by Vancouver to speak and to listen. When Canada joined the war against Japan these Chinese-Canadian political organizations were elevated in status, a recognition that China was an ally in the fight for freedom.

* * *

500 Canadian-born Chinese enlisted in the Canadian military and Chinese-Canadians bought more than $10 million in Canadian war bonds ($157 million today). The fight for a common cause softened the racial prejudices of many white Canadians.

War brought about radical change in the Chinese community too, as women broke free from their traditional gender roles. As one historian noted, ""The appearance of Chinese women selling tags on the streets of Canada's major cities was one of the most remarkable and interesting phenomena of the war years."1

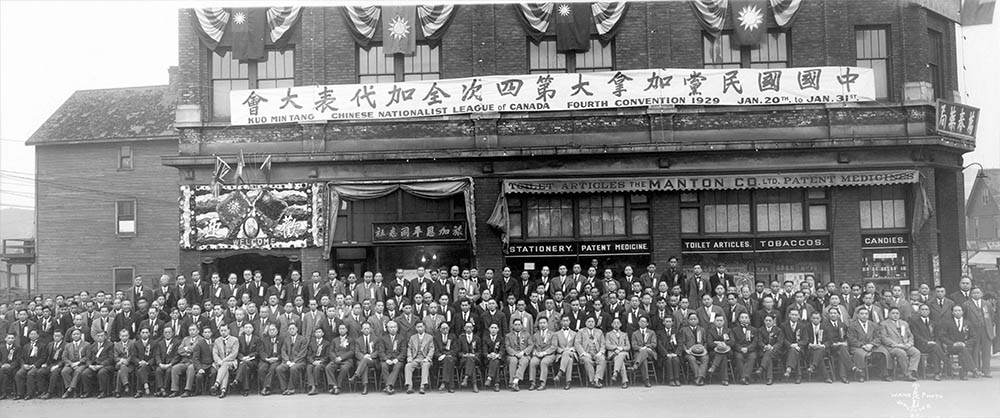

15. The Barriers Come Down

Vancouver Archives AM1108-S4-: CVA 689-156

1929

A group photo for a meeting of the Kuomintang, the political party of the Nationalist Government in China. After the war relations began to stabilize and the racist laws were rescinded.

* * *

The Chinese Immigration Act was repealed in 1947, along with a variety of other racist statutes. Chinese were now able to vote and enter the professions. Within months the first Chinese Canadian had passed the bar.

It took longer for the government to recognize the heritage and cultural value of Chinatown itself. In the car mania sweeping North America in the 1950s and 1960s, Chinatown was slated for demolition to make way for an expressway. Thankfully, a vigorous grassroots campaign derailed this plan and the only parts of it ever built were the Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts.

In 1971 Chinatown was declared a national historic site, but the focus of the Chinese community had already begun to shift south, to Richmond.

That so much of Chinatown survives today is a testament to the grit and determination of pioneers a century and more ago, who crossed the ocean to a strange new land and forever left their mark upon it.

Endnotes

2. Chinese Pioneers

1. Con, Harry. From China to Canada. A History of the Chinese Communities in Canada. Toronto: Canadian Publishers, 1982.

3. Coming to Canada

1. Encyclopedia Britannica.

2. Con.

4. Shanghai Alley

1. Snyders & O'Rourke.

5. Finding Work

1. Anderson.

2. Con.

6. Growing the Community

1. Davis.

2. Stanley, "Yip Sang."

7. Sam Kee

1. Stanley, "Chang Toy".

8. Chinatown Arch

1. Con.

9. Organizing the Community

1. Con.

10. The Race Riot of 1907

1. Takata.

2. Con.

11. Racist Myths

1. Con.

2. Howard.

13. Aiding the War Effort

1. Con.

14. An Early Political Meeting

1. Con.

Bibliography

Anderson, Kay J. Vancouver’s Chinatown: Racial Discourse in Canada, 1875-1980. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 1991.

Con, Harry. From China to Canada. A History of the Chinese Communities in Canada. Toronto: Canadian Publishers, 1982.

Davis, Chuck. History of Metropolitan Vancouver. Vancouver: Chuck Davis Estate and Harbour Publishing, 2011.

Editors. "Taiping Rebellion." Encyclopedia Britannica. 8 Dec. 2015.

Howard, Hilda. The Writing on the Wall. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1989.

Snyders, Tom & O'Rourke, Jennifer. Namely Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2001.

Stanley, Timothy. "Chang Toy." Dictionary of Canadian Biography.Online.

Stanley, Timothy. "Yip Sang." Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Takata, Toyo. Nikkei Legacy: The Story of Japanese Canadians from Settlement to Today. Toronto: NC Press, 1983.