Walking Tour

People of the Safe Harbour

A History of Ucluelet

By Alexa Dagan

Ucluelet, a Nuu-Chah-Nulth word meaning "people of the safe harbour," perfectly fits this pretty fishing village on the sheltered shore of Ucluelet Inlet. The town's harbour is a calm oasis framed by soft ocean mists surrounded by a ferocious and unpredictable sea. The Nuu-Chah-Nulth have lived in the village on the east shore of the inlet for thousands of years, while the European settlement on the west shore, now known as Ucluelet, is less than 150 years old. However, a lot has happened in that century and a half, and the beauty and abundance of Ucluelet has attracted all sorts of people: gardeners and pioneers, artists and fishermen, hippies and loggers.

This tour looks at the unique challenges and joys that came from living on the edge of the Pacific Ocean, though it sometimes felt like living at the edge of the world. We will examine Ucluelet's vibrant history, from its beginnings as a fishing village, looking at the perseverance of its early settlers, to its growth into a logging town, and finally into the tourist hub it is today.

This tour begins at the intersection of Waterfront Drive and Bay Street with the first European pioneers. We will learn what drew them to the area and the difficulties they overcame in establishing Ucluelet. Then, we'll make our way to the Government Wharf where we will learn about this community's close ties to the sea.

From there, we will leave the busy downtown centre for a brief stroll along Imperial Lane towards the long dock at the end of Otter Street, where we will learn about the history of the Nuu-Chah-Nulth and Japanese in this community, as well as the remarkable story of George Fraser. Getting down to the dock requires going down a long flight of steps, but you will be rewarded with excellent views of the harbour.

Finally, we return downtown and uncover the reason for the end of Ucluelet's decades of isolation and the changes triggered by the opening of the Pacific Rim Highway.

This project is a partnership with Tourism Ucluelet. We also owe thanks to the generous support of the Ucluelet and Area Historical Society.

1. The Early Years

Ucluelet & Area Historical Society 46a

1930s

In this photo a man and woman supervise a house-carrying semi-truck as it navigates a tight corner. The house was owned by Ted Welland, and was en route to its resting place at the top of Bay Street and Peninsula, before Peninsula was extended south. The process of transporting it by truck illustrates a major challenge Ucluelet's early settlers faced: access. Today, getting to and from Ucluelet is as simple as hopping in a car and driving along the Pacific Rim Highway to Port Alberni. This wasn't always the case; from the first Europeans settlers in the 1860s until the highway was officially opened in 1959, Ucluelet could only be reached by sea or air.

* * *

The HBC's William Banfield became the first European settler in Barkley Sound (at which Ucluelet is at the northern edge). At the time, the area was being carefully charted on maps and British names were being affixed to natural features that had gone by Indigenous names since about the end of the last ice age. Banfield found the practice distasteful. He wrote:

"However much the old navigators' names are entitled to respect, good taste would leads us at the present day to adopt the Indian names [which] in most instances are much prettier, many of them having a natural beauty of sound... Great Britain's colonies have enough Royal names, noble names, and titles of our grandfathers and grandmothers and birthplace names."1

Apparently the cartographers didn't care, as after he died, the town of Bamfield on the opposite side of Barkley Sound was named after him anyway. As you can see, they also spelled his name wrong. .

Thankfully, his advice was followed with Ucluelet, which kept its Nuu-Chah-Nulth name when Banfield's associate Captain Charles Stuart became the first European settler here in 1860. Stuart, who had been fired as the HBC's chief factor (almost a kind of governor) of Nanaimo for frequent drunkenness, ran a small trading post beside the village on the opposite side of the bay until his death in 1863. Other early traders were Captain Peter Francis and Captain William Spring. They eventually became partners, sharing a fleet of sealing ships. The two entrepreneurs also ran a trading post situated in the cove which now bears Spring's name; Spring Cove is situated near the mouth of Ucluelet Harbour.

Ucluelet harbour was ideally situated for a trading post, and as a secondary advantage the surrounding waters teemed with marine life. Hugh McKay, one of the first European traders in the region, reported to the Victoria newspaper The British Colonist in 1859 that the waters off of the west coast of Vancouver Island were "alive with fish," and soon after Capt. Francis consolidated the post, fishermen from all corners of the world began to flock to Ucluelet.2 As the fur trade entered rapid decline, products derived from fish, seals, and whales became Ucluelet's primary export.

2. Pioneers

Ucluelet & Area Historical Society

1900s

This photo shows Ucluelet when it was a small scattering of buildings in the centre of a large deforested area on the shore of the inlet. The elegant Victorian home featured in the photograph belonged to the Lyche family, and the emptiness of the surrounding landscape highlights the hurdles pioneer families faced in settling this corner of Vancouver Island.

Every Canadian town has key pioneers in its history, early figures who left a lasting fingerprint on the community's collective memory. Ucluelet is no exception to this. Of several founding families, who left their mark on the young community, the Lyches stand out prominently in Ucluelet place names. Their impact is seen through three things being named after them: the small island just off Ucluelet's main wharf, a key road skirting the boat basin, and the District Office.

* * *

After making Ucluelet his permanent home in the 1890s, August married Alice Greenwood Lee, formerly of Victoria, and later became Ucluelet's first teacher at the small schoolhouse that was built where the municipal building stands today. They soon had children, and the growing family kept themselves very busy, as they were fishing, farming, and running the local hotel.

It can be difficult for us today to imagine starting a community pretty much from scratch. The first task was to clear the trees. Before the invention of the chainsaw and the automobile, clearing the land for settlement was a significant undertaking, "Even if you succeeded in knocking one of these monsters [trees] over, how would you dispose of it, much less remove the sprawling stump so you could do something useful with the land such as plant crops or feed your animals?" These were questions that early settlers must have asked themselves as they studied the landscape that opposed their every move.2

As you can see from the home in this photo, the Lyches, like some of Ucluelet's other pioneers, went to impressive lengths to adapt Victorian lifestyles to this remote community, where creature comforts were limited. They built beautifully finished houses with stained glass windows and vegetable gardens, and imported pianos and other fine furnishings. Everything had to be brought in by boat, except lumber, of which there was no shortage. In the early years, Ucluelet was cluttered with stumps and piles of debris scattered everywhere, refuse left behind after clearing the land. But despite looking more like a clear cut than a settled community, the insides of the Victorian homes were reportedly as fine as any found in Victoria or Nanaimo.

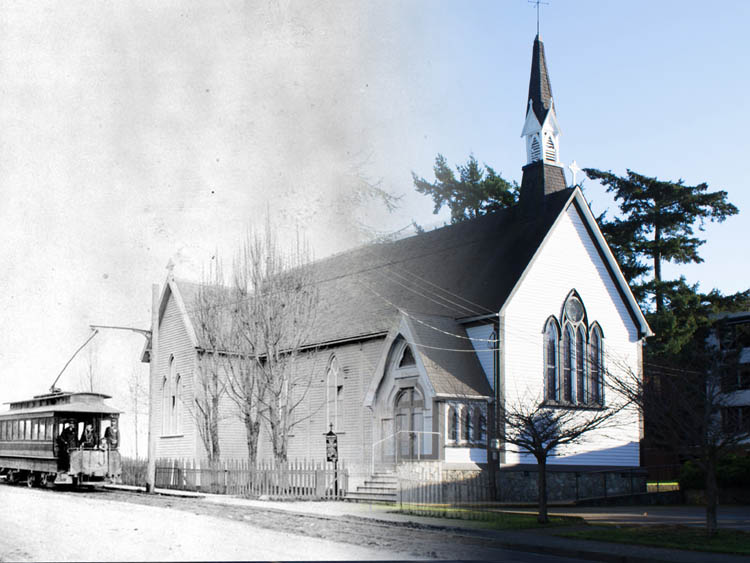

Growth was slow in Ucluelet; by 1899 Ucluelet only had a population of 15 European settlers, living across from 200 Nuu-Chah-Nulth on the other side of the inlet.1 However, thanks to the prodigious efforts of pioneers like the Lyches, the foundations of the little town had been laid. There was a doctor, a school, and a church, while a Canadian Pacific Railway steamship visited the community three times a month.

As early as 1911 rumors swirled that a road to Port Alberni would soon be built, and expectations of all the benefits that would bring helped draw yet more settlers to the community.2 If the settlers knew then that it would end up taking almost half a century for the road to get built, some might have been a little more hesitant before taking on the challenge of life in Ucluelet.

3. A Treacherous Lifeline

Ucluelet & Area Historical Society

1950s

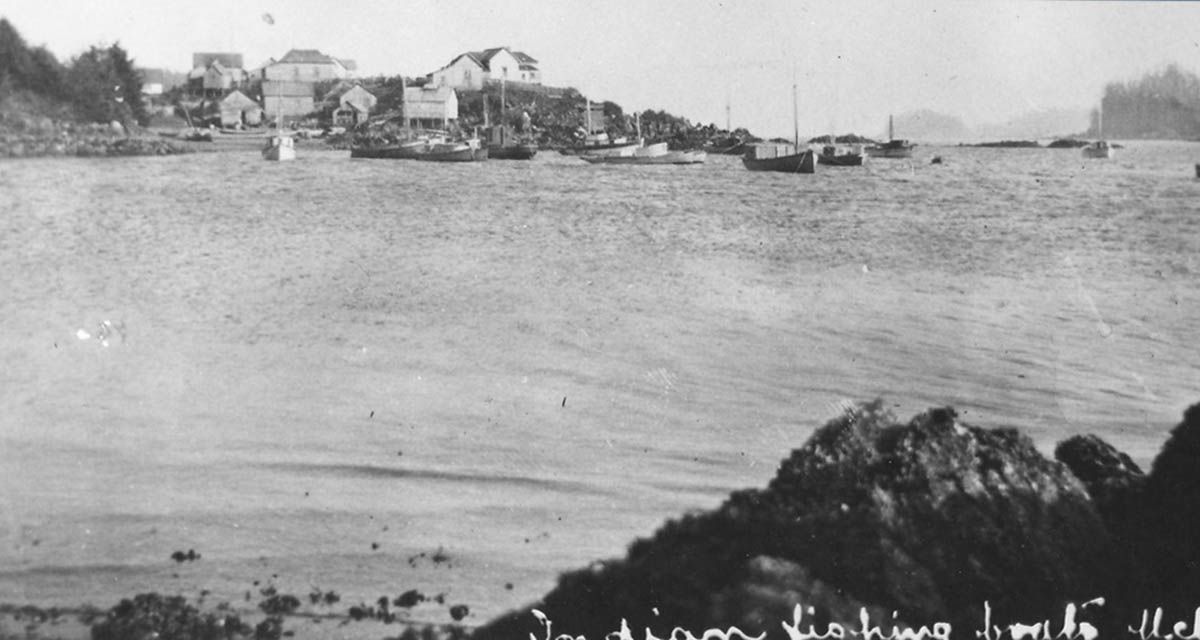

This photo shows Ucluelet as a firmly established community. Quaint little fishing boats crowd around a dock in the inlet and the chimneys of the large stately houses emit plumes of smoke that mingle with the ever-present coastal mist. As a community entirely dependent on ocean links to the outside world, the ebbs and flows of community life were tied as closely to the arrivals of steamships as the ocean tides are to the moon. "Boat Days" as locals called those arrivals, brought the entire community together in a festive atmosphere as everyone congregated on the docks to greet the arrival of shipments, mail, and visitors.

* * *

While the ocean was Ucluelet's lifeline, the journey to communities on the west coast was fraught with danger, and even the most experienced captain was tested by the tricky inlets, thick fog banks, and barely submerged reefs. These hazards were exacerbated by a sparsely populated coastline that had few lighthouses and meager rescue infrastructure.

It is for these reasons that the coastline from the northern tip of Vancouver Island down south to Oregon has earned the ominous nickname the 'Graveyard of the Pacific'. The Vancouver Island section of the Graveyard has claimed at least 484 ships and thousands of lives.1 It is often said there is a major shipwreck for every mile of Vancouver Island's west coast. Even today, ships equipped with space-age navigational tools occasionally run aground on this treacherous coast.

Even by the grim standards of the 'Graveyard of the Pacific', the waters around Ucluelet and adjacent Barkley Sound are especially deadly.

On December 26, 1905, The Pass of Melfort was wrecked near the mouth of Ucluelet Harbour. Caught unprepared in a sudden winter storm and pummelled by giant swells, the four-masted barque was dashed against a reef only a few metres from shore. Despite the proximity of land, the raging storm made escape from the sinking ship impossible and the vessel was torn to shreds on the unforgiving rocks. By the next morning, all that remained of the Pass of Melfort was some washed up debris floating in a sheltered cove nearby. None of the 27 passengers and crew survived. This tragedy was the impetus in the building of a lighthouse on Amphitrite Point. The first structure, a wooden tower, lasted from 1906 to 1914, when a freak wave washed it out to sea. A more solid structure was built in 1915 and still stands today. The site of the wreck is visible from the scenic Wild Pacific Trail, which circles Amphitrite Point.2

4. The Pacific War

Ucluelet & Area Historical Society 008 67

1920s

In this photo, an interesting seaplane docks near the fishing boats at the Government Wharf as a curious crowd looks on. The first seaplanes were developed in France around 1910, planes that could land on water were ideal for accessing remote communities along British Columbia's rocky coast and for Ucluelet they became an important new link to the outside world lifeline after the 1920s. The importance of seaplanes and flying boats was vividly illustrated during the Second World War, when the Royal Canadian Air Force set up a seaplane base in Ucluelet, which is the subject of another walking tour.

* * *

For people in Ucluelet the threat of war was real enough. Measures like mandatory blackouts, rationing, and evacuation plans were enacted. Ken Gibson, a Tofino resident recalled: "You had to have buckets of sand upstairs in the attic in case of incendiary bombs… you really knew there was a war going on." Another local too, remembers the war measures, "The threat of attack was so real that the military authorities insisted a box of groceries be kept in every home in case it became necessary to evacuate all the women and children. I carried a gun in my car at all times as did many others."1. Some Ucluelet men served overseas, while others volunteered to join the Pacific Coast Rangers and were issued with 30-30 Winchester repeater rifles, though these would be of dubious worth in the event of an invasion.

Fortunately, the Japanese were never in a position to actually invade Canada's west coast. The closest they came was seizing Attu and Kiska in Alaska's Aleutian Islands in June 1942. However, Japanese submarines did make some forays into BC's waters, torpedoing two ships in the Juan de Fuca Strait that same year. When a Japanese submarine surfaced off Estevan Point, about 50 km north of Tofino, and unsuccessfully shelled the lighthouse there, it caused a frenzy of media speculation about looming Japanese attacks. The residents of Estevan Point and Hesquiat village were quick to recover from the shock and took to the beach the next morning to search the sand for shell fragments.

All of this occurred in 1942 at the peak of Japanese success in the Pacific War, and almost immediately the rising tide of Japanese empire began to ebb. Expansion into the Western Pacific was halted decisively by the Americans at the Battle of Midway, while in the south they were checked by the Americans at Guadalcanal, and British and Indian forces in Burma. By 1943, that threat to Canada's west coast had receded, and the people of Ucluelet could breathe a sigh of relief.

5. The Fishermen

Ucluelet & Area Historical Society 990-27

1910s

Right now, you are looking across the inlet, think of what this spot looked like in the past. You are probably picturing something similar to what you see now, maybe with a house or two less. However, the truth might be surprising - you are looking at what used to be a thriving center of industry. One Ucluelet resident recalled days when the inlet was so "thick with fishing boats that you could walk across the inlet without ever touching water."1

In this photo a giant plume of dark, greasy smoke pours out of the burning Port Albion cannery. The cannery, like many others across coastal BC, was built to harvest abundant Pacific Salmon. However, as lucrative as canneries could be, they were also highly flammable. The buildings, constructed from wood and balanced atop wooden pilings, were heated by wood stoves, used giant boilers, and--in the early days--were lit by oil lamps.

* * *

European settlers and the Nuu-Chah-Nulth had fished the waters of Ucluelet with huge success, but some of the greatest contributors to Port Albion's cannery were the Japanese-Canadian fishermen who called Ucluelet home.

Initially, Ucluelet's locals met the new group of highly skilled fishermen with some reservation. As their boats began to crowd the harbour, local fishermen protested at how many fishing licenses were being given to the newcomers. But, even so, the locals couldn't help but be impressed by their skills:

"Boy, they were good, they made all their own spoons [fishing lures]. They'd get these big pieces of brass and cut them and polish them up and bend them they way they wanted them Then they'd try them in the water, pulling them along to see they worked right. I fished right along with them. They were really good."2

Despite some initial tension, the Japanese-Canadians soon became valued members of the community. By World War II, the Japanese community in Ucluelet numbered over 200, significantly contributing to the population of the small village.3 Japanese-Canadian children went to the same school as the European ones and they formed deep, life-long friendships. The children were baffled when events thousands of kilometres away suddenly caused the atmosphere to change.

Following Imperial Japan's assault on British and American possessions across the Pacific, some people on the Canadian west coast became mistrustful of their Japanese neighbors.

In 1942, the federal government declared all Japanese in Canada to be enemy aliens. After the order came down, things moved quickly; all those of Japanese descent, regardless of birth or citizenship, were to be forcibly evacuated from the coast and moved at least 160 km inland. Officials gave Japanese-Canadians in Ucluelet less than a day to get their affairs in order before they were rounded up and shipped to internment camps in BC's interior. Every possession that they couldn't take with them--including the fishing boats that provided their livelihoods--were sold off by the government at bargain basement prices.

Peter Mayede, born at Sanahama Bay in Ucluelet, related memories of the evacuation to Pieter Timmermans: “We had two days notice to pack up necessities, we were allowed two suitcases, the rest was piled on the beach and burned.”

After the war, many BC politicians advocated forcibly deporting all the Japanese-Canadians to Japan. Several thousand were deported before the policy was finally halted in 1947. Unsurprisingly, the years of internment, humiliation, and loss of property meant most Japanese-Canadians were reluctant to return to their homes on the coast, and many resettled in eastern Canada, especially around Toronto.

In Ucluelet, the close ties forged before the war between the Japanese, First Nations and European communities ensured that this community was a welcome exception. Twelve families chose to return, although they found upon their arrival that their houses had been sold.4 The evacuation and internment remain a dark period of BC history, but today Ucluelet celebrates the contributions the Japanese-Canadians have made to the town's history and are grateful for those families that did choose to return.\

6. Hitacu

Ucluelet & Area Historical Society 009 19

1910s

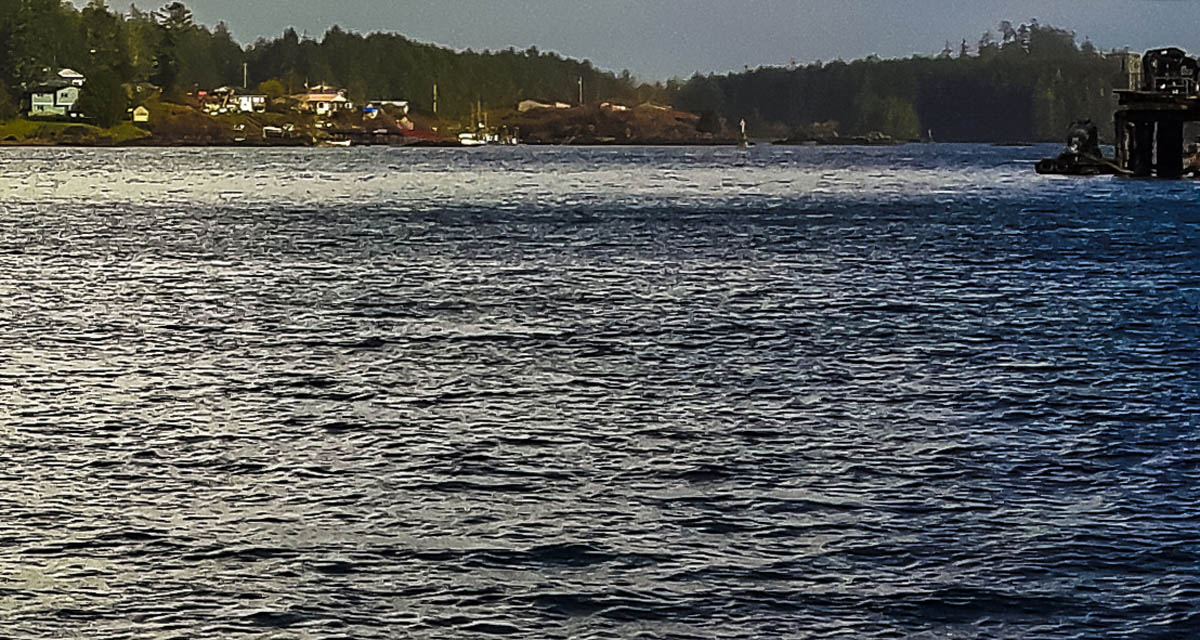

Standing on this dock offers a view of the best Ucluelet offers: picturesque seaside houses, the back-and-forth of fishing boats, and the lazy groan of sea lions, made eerie by a thin veil of damp coastal mist. Across the inlet, a small huddle of houses peers through the fog, both now and in this historic postcard from 1918. This is Hitacu, the community in Ucluelet East.

Hitacu is the ancestral home of the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ (pronounced yoo-thlew-ilth-uhht) Nations and the site of their treaty government. Hitacu is home to a little over 200 people and is now entirely self-governing thanks to a 2011 treaty signed between the provincial government and the five nations of the Maa-Nulth First Nations.1

* * *

The way of life of almost every indigenous nation in the Pacific Northwest revolved around the gigantic dugout cedar canoes. The Nuu-Chah-Nulth were particularly renowned for the daring and skill they exhibited in the whale hunts that they had been conducting from these canoes for over 4,000 years.

The process was long, arduous, and exceptionally dangerous. In the spring, after complex and highly choreographed traditional rituals, the Nuu-Chah-Nulth hunting party would take to the Pacific in dugout cedar canoes up to eleven metres long. Upon spotting a whale, hunters struck it with harpoons, each with a sealskin float affixed to it with rope. The floats effectively impeded the whale's ability to dive and maneuver, and by the end of the struggle often as many as fifty floats were affixed to the exhausted whale.

Eventually, the equally weary hunters could surround the severely weakened whale and deal the final blow. For the hunters though, one trial remained: bringing their trophy home. Hunting a whale could lead a crew deep out to sea, leaving the men with the herculean task of towing a sea mammal weighing the equivalent to that of six African elephants back home.

In July, the whaling season became the salmon season, as millions of Sockeye returned to their spawning grounds. In early fall a final run of dog salmon provided another source of sustenance. For millennia, the Nuu-Chah-Nulth had lived according to this rhythm of the seasons.

This rhythm was disastrously and irrevocably altered with the arrival of Europeans. Traditions and rituals that had been practiced for millennia were outlawed. The First Nations were frequently removed from their traditional hunting grounds and villages to be relocated to reserves. Their children were subjected to the Residential School system, which aimed to assimilate them more effectively into European culture, but ultimately resulted in long-term generational trauma.

"Into their world came heavily armed strangers determined to impose their mores, institutions, and religion on the local people," write authors Margaret Horsfield and Ian Kennedy. "All too often these strangers assumed that the land, with its complex traditional territories and its hierarchical, deeply rooted patterns of ownership and use, could be theirs for the taking."3

Now, having regained their right to self-govern, the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ and the community of Hitacu are spearheading a series of programs to revitalize and preserve their language and culture, and stimulate a thriving local economy. These enthusiastic efforts towards cultural revitalization and celebration reflect others taken by First Nations peoples across the country, and represent one aspect of a long process of recovery from years of systematic oppression.

7. Ucluelet's Grandfather

Ucluelet & Area Historical Society 990-92

1920s

The aging gentleman in this picture has a most grandfatherly look. Wearing a fraying, much loved cardigan, heavy boots, and bushy eyebrows, he has the slightly stooped posture of someone who has spent much of their life hunched in a garden. George Fraser was one of Ucluelet's key early pioneers, but he is more famous for putting Ucluelet on the horticultural map with the dozens of rhododendron hybrids he lovingly developed here. Have a look around town and you'll be sure to notice many beautiful, monstrously huge, rhododendron bushes towering over the diminutive petunias and begonias. Many of these thriving flowers were taken from the bushes Fraser himself engineered. This photo was actually taken a short ways from here, on what were once his extensive properties, but it is now private property.

* * *

Evidently Fraser wanted something a bit more challenging, and when he saw that most of the Ucluelet peninsula was up for sale, he bought it--236 acres for $236. Arriving in 1892, he was one of the first European pioneers and his land holdings extended from the southern tip of this peninsula north to just short of Main Street, including the land you are standing on right now.

Alongside all the challenges of early pioneer life in Ucluelet, Fraser soon began indulging in his true passion: rhododendrons. He set aside 4 acres of his land as a nursery and park which, unfortunately, does not survive today, although it was just a couple hundred metres from this spot. There, he began experimenting with different hybrids of rhododendrons, ingeniously breeding them with honeysuckle, gooseberries, and roses.

Fraser's project was no easy task as the tough soil was better suited for growing hemlock, balsam, and red cedar. To make it more suitable for growing more delicate plants and flowers, Fraser manually carted to his garden cow manure and seaweed as fertilizer. Once he had finally made the soil suitable and the seedlings began to erupt, Fraser was horrified to discover that the local deer also enjoyed the fruits of his labour.1

Over the decades, Fraser's flowers brought Ucluelet international fame, and horticulturalists from around the world would make the voyage to Ucluelet to see his famous nursery. The proliferation of his rhododendrons around Ucluelet might have had something to do with his practice of gifting every newly married couple in Ucluelet and Tofino with one of his beloved rhododendron hybrids.

Like Fraser, many of Ucluelet's settlers faced challenges in adjusting to their new landscape. Many keenly felt the isolation brought on by living in such a remote community and the relatively limited access to amenities. Over time, Ucluelet developed necessary amenities such as schools and churches, but settlers also attempted to bring beauty and art to their new community as well. Some of the region's wealthier families had pianos shipped in, some planted flower gardens, or in the case of visiting artist Emily Carr, sketched their local surroundings.

George Fraser wasn't the only one who saw opportunities for beauty in Ucluelet's rugged surroundings. Emily Carr, one of Canada's most treasured painters, was fascinated by the west coast, and particularly by First Nations people and their art. She made the first of several sketching trips to Ucluelet in 1898, where she stayed with the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ First Nations, who soon gave her the name Klee Wyck, meaning, "the Laughing One." She was inspired by Ucluelet's rugged wilderness and ancient traditions of the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ and the Nuu-Chah-Nulth, and these experiences heavily influenced her later sketching trips across the Pacific Northwest.2

As for Fraser, in 1944 at the age of 90 he left Ucluelet for the last time. His final words might encapsulate the draw this place has had on people for millennia: , "I don’t know where I’m going to end up, but it doesn’t matter – I’ve had my heaven here on earth."3

8. A Highway at Last!

Ucluelet & Area Historical Society 008 21

1960s

In this photo, taken in the heart of downtown Ucluelet, classic 50s cars line the road. Until the highway to Port Alberni opened in 1959, the locals had few places to take them. They could go to Tofino, though the real road there was only completed during World War II. Before then, there was an alternate way to get to Tofino: in the Ucluelet Archives, there are dozens of photos depicting a scene that seems bizarre to us today - vehicles driving on Long Beach. Rather than risk the iffy corduroy road made of logs through dense forest, locals figured that the 16 kilometer stretch of beautiful sand made for much easier and more scenic driving, and Long Beach was the easiest leg of the otherwise awful drive to Tofino.

* * *

The 1950s brought renewed hope for a highway. Lumber companies had taken notice of the region's valuable old growth forests and began pushing the issue. In the post-war economic boom, there was more money available for infrastructure projects like this, and finally contracts were signed and construction began.

August 22, 1959 was a momentous day for the little community. After almost seven decades without road access, the Pacific Rim Highway had finally opened. Almost every functional automobile in Tofino and Ucluelet was assembled to take part in an inaugural drive on the new road. Curiously, the road builders went to the efforts of getting every driver to sign a damage and injury waiver before taking part.

The Pacific Rim Highway was not a road to be taken lightly and bore more likeness to a temporary logging road than a public highway. Initially, it was gravel surfaced, filled with winding switchbacks, steep climbs and drops, mudholes, and several creek crossings. The uninitiated often arrived in Ucluelet shaken, vehemently refusing to drive home again. The highway wasn't well maintained either, and the frequent storms washed away large sections. In 1961, a fed up resident took matters into his own hands and commandeered a Department of Highways grader and graded a particularly harrowing 5 kilometer stretch himself. He was subsequently slapped with a hefty fine for the trouble.1

The highway marked a new phase in Ucluelet's history, as easier access opened up the region's rugged beauty and pristine beaches to the wider world. As word of the place spread, tourists began to flock to Long Beach in droves. A favourite pastime was to race cars on Long Beach, an activity made more exciting by the various anti-invasion obstacles that remained on the beach from the Second World War. Many of these races ended predictably with cars abandoned in soft sand or rescued by exasperated tow-truck drivers.2

Surfing, of course, quickly became popular in this time period too. In 1966 the Jordan River surf club sponsored Canada's first international surfing competition on Long Beach. The rising prominence of this new activity would completely transform Ucluelet.

9. The Hippies Are Coming

Ucluelet & Area Historical Society 008 52

1940s

This thrift store, perched on the steep corner between Peninsula and Main Street, is one of Ucluelet's oldest buildings. Although the paint is different, the doors and windows have moved around, and the block is a little more crowded than it once was, the former Ruth's Gift Shop is still one of the centerpieces of this thriving community. With tourism now dominating the local economy, gift shops are now some of the most common retail spaces in Ucluelet. 1

* * *

Tourism here began early. Some of the first pioneers, the Lyches, opened a hotel, and as early as the 1890s, Captain Gillam would delay the departure of the steam ship the Princess Maquinna to allow visitors time to explore George Fraser's garden.

10. The War in the Woods

Ucluelet & Area Historical Society

1910s

Much like Ruth's Gift Shop, the Crow's Nest general store is a survivor from Ucluelet's early years and holds the title of Ucluelet's oldest storefront. Originally built by pioneer Edwin “Ned” Lee, Lee's General Store, later Maddens General Store, supplied early settlers with the basic necessities. It operated in this capacity for an impressive 80 years before changing with the times to become a gift shop. It still retains its eclectic general store vibe with original fir floors, and by selling everything from crafts and souvenirs to office supplies and printing services.1

While Ucluelet's shift from small industry town to tourist haven was gradual, it was far from seamless. The Pacific Rim highway opened access to tourists, but was really intended to improve access for loggers. Logging had long been a vital industry in the region, and the road opened hundreds of hectares of previously inaccessible forests for harvest. The boom supplied high-paying logging jobs to many people in Ucluelet, and greatly aided the community's prosperity. Yet this increased emphasis on logging would soon clash with changing cultural attitudes towards the forests that surround the community.

* * *

These high risk, high reward days were coming to a close. Many of the tourists who were drawn to the region by its natural beauty were horrified by the scars landscape left by clearcuts. As many people in BC increasingly championed environmental causes after the 1960s, the loss of BC's magnificent and ancient old growth forests was becoming a heated political issue. The dispute over the use and protection of BC's forests pitted the locals who relied on forestry for their livelihoods against environmental activists, many of whom came from outside the region, in a grim conflict that would culminate in the events of the so-called "War in the Woods."

In 1993, Clayoquot Sound became the stage for the largest act of civil disobedience in Canada's history, as 12,000 people converged on the area to protest logging operations. Approximately 1,000 people of all ages, and walks of life were arrested, but they were ultimately successful in their cause, and the logging industry in Clayoquot Sound swiftly declined. The communities of Tofino and Ucluelet were deeply divided on the issue and felt the effects of the conflict most keenly. The loss of the lumber industry resulted in the loss of many high-paying jobs in Ucluelet especially. While tourist dollars trickled in to fill the void, Ucluelet received less visitors than Tofino, and jobs in tourism simply didn't pay as well. It remains a sensitive issue today, not only in Ucluelet, but province-wide, as lumber remains one of the province's foremost industries, even as only a fraction of the old growth forests remain.

Endnotes

1. The Early Years

1. Margaret Horsfield and Ian Kennedy, Tofino and Clayoquot Sound: A History (Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2014), 168.

2. Horsfield and Kennedy, 165.

2. Pioneers

1. E. A. Hillier, "History of Ucluelet 1899-1954," Mark Penney Gallery, online.

2. Mark Penney Gallery, online.

3. A Treacherous Lifeline

1. Fred Rogers, More Shipwrecks of British Columbia, (Madeira Park: Douglas & Mcintyre, 1992).

2. Wreck Site, "Pass of Melfort," Feb. 13, 2017. Online.

4. The Pacific War

1. Horsfield and Kennedy, 392.

5. The Fishermen

1. Interview

2. Horsfield and Kennedy, 323.

3. Horsfield and Kennedy, 323.

4. Horsfield and Kennedy, 419.

6. Hitacu

1. West Coast N.E.S.T., "Hitacu," 2019, Online. https://www.westcoastnest.org/communities/hitacu

2. Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ, "Government," 2019. Online.

3. Horsfield and Kennedy, 40.

7. Ucluelet's Grandfather

1. Jackie Carmichael, "Ucluelet event salutes George Fraser, his legacy," Tofino-Ucluelet Westerly News, July 2, 2014.

2. Andrew Bailey, "Cultural Heritage Festival celebrates Emily Carr," Tofino-Ucluelet Westerly News, August 26, 2016.

3. Carmichael.

8. A Highway at Last!

1. Horsfield and Kennedy, 441.

2. Horsfield and Kennedy, 440.

9. The Hippies Are Coming

1. Horsfield and Kennedy, 450.

10. The War in the Woods

1. "The Crow's Nest Ucluelet," The Crow's Nest, 2013. Online.

2. John Vaillant, The Golden Spruce: A True Story of Myth, Madness and Greed, (Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2006), 27.

Bibliography

Bailey, Andrew. "Cultural Heritage Festival celebrates Emily Carr," Tofino-Ucluelet Westerly News, August 26, 2016. Online. https://www.westerlynews.ca/entertainment/cultural-heritage-festival-celebrates-emily-carr/

Carmichael, Jackie. "Ucluelet event salutes George Fraser, his legacy," Tofino-Ucluelet Westerly News, July 2, 2014. Online.

Hillier, E. A. "History of Ucluelet 1899-1954." Mark Penney Gallery. Online. http://www.markpenneygallery.com/history-of-ucluelet/

Horsfield, Margaret & Kennedy, Ian. Tofino and Clayoquot Sound: A History (Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2014.

Rogers, Fred. More Shipwrecks of British Columbia. Madeira Park: Douglas & Mcintyre, 1992.

The Crow's Nest. "The Crow's Nest Ucluelet," 2013. Online. http://www.crowsnestucluelet.com

Watson, Gordon M. "Letters: A National Park at Risk," The New York Times, Nov. 26, 2006. Online. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/24/travel/escapes/24letters.html

West Coast N.E.S.T. "Hitacu." 2019, Online.

WreckSite.eu, "Pass of Melfort," Feb. 13, 2017, Online. https://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?167255

Vaillant, John. The Golden Spruce: A True Story of Myth, Madness and Greed, Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2006.

Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ. "Government." 2019. Online. http://www.ufn.ca/our-government/