Walking Tour

Working in Okotoks

The Jobs, Industries, and Characters

Elyse Abma-Bouma

When Okotoks opened to European settlement with the arrival of the railway in the 1890s, hundreds of immigrants were drawn to this spot alongside the Sheep River. They were drawn by the jobs and opportunities presented by the new industries that grew up here, such as sawmills, ranches, and brickworks. Just as important were the merchants who established shops that provided Okotokians with all the goods and services that made daily life possible. On this tour we will look at some of these jobs and industries, and some of the prominent figures who helped build Okotoks.

This tour is a short walk that begins at the Okotoks Art Gallery on North Railway Street, the site of the old railway station. From there we'll walk west along North Railway Street and McRae Street in the historic downtown. Finally we'll walk to the edge of the Sheep River where the sawmill once stood, and reflect on how the jobs have changed.

The land on which you'll be walking is the traditional territory of the People of Treaty 7 which includes the Blackfoot Confederacy comprised of the Siksika, Piikani and Kainai First Nations, as well as the Metis Nation of Alberta, Region 3.

This project is a partnership with the Okotoks & District Historical Society. We also would like to thank the Ridge at Okotoks for sponsoring our work trip.

1. Okotoks Gets Its Start

1909

This is the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) station at Okotoks. This is an appropriate place to start this tour because it's where most settlers in Okotoks first set foot when they arrived here seeking out a new life. In an era before widespread car ownership and highways, the train station became Okotoks’ gateway to the outside world.

The original station on this spot was completed in 1892, but burned down in 1928 and was replaced with the brick station you see today. This station functioned until 1971 when passenger rail service ended. Given the building's historic importance, the Okotoks Arts Council and Town of Okotoks worked together to preserve the station and turn it into a cultural hub, a purpose it continues to fulfill today as an art gallery.

* * *

Okotoks was different: it predated the railway. It was located on the Macleod Trail, the transportation route that connected Fort Calgary and Fort Macleod. The trail was used by bull trains carrying heavy loads of supplies, horses and riders, as well as stagecoaches. Southbound stagecoaches, carrying both passengers and mail, made it as far as Okotoks in a single day and stopped here for the night before fording the river in the morning. One of the first two pioneers to settle in Okotoks, Kenneth Cameron, recognized a business opportunity and, in 1882, built a stopping house -- similar to today's bed and breakfast-- for travellers to rest along their journeys.

More settlers were drawn to the site by its natural beauty, proximity to Calgary, and access to a supply of fresh, clean water. By 1887 the Okotoks area had 20 homesteads and two stopping houses.1

In the late 1880s and early 1890s, Donald Morrison and John Lineham (more about him later) established sawmills in Okotoks. In fact, the lumber industry would become the backbone of the Okotoks economy for the next 25 years.2

When the Calgary and Edmonton Railway laid the Calgary to Fort Macleod rail line through Okotoks in 1891, the community was already well established. Lineham’s sawmill was even able to supply the railway with ties for laying the track. This meant the railway and its affiliated land speculators had far less control over the community's early development than many other towns on the Canadian prairies. This can be seen in the street layout, which doesn't quite conform to the standard grid pattern that is the hallmark of railway towns: the angled portion of main street (now North Railway Street) follows the route of the old Macleod Trail.

It can also be seen in the names of the streets, which are named for those first pioneers and their families (Lineham, Elma, McRae, Daggett) rather than for railway men and realtors. As the historian Lewis Thomas stated, "Okotoks, almost alone among the towns along the Calgary and Edmonton Railway, does not have streets consecrated to those tutelary spirits of land speculation, Osler, Hammond and Nanton."3

Nevertheless, the arrival of the railway was a defining moment in the town's history. As Okotoks historian Kathy Coutts explains, "The train station connected local residents with the rest of the world. It brought mail, it brought new residents, visitors, investors, connected communities, and brought convenience."4 The day-long journey to Calgary was suddenly reduced to an hour, and serviced by four passenger trains a day.5 The opening of the railway began Okotoks’ journey from a cluster of simple wood houses and stopping houses to a thriving town.

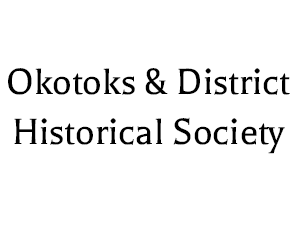

2. The Postal Service

Several people on horseback pose for a photo in front of the Okotoks Post Office in 1921. The building next to it is the Star Restaurant, one of Okotoks’ first restaurants. John Paterson--who also ran the Paterson and Sons General Store to the west--was postmaster until his son George succeeded him in 1909. George served as postmaster until his death in 1942, and was an important figure in the community; he also served as mayor in 1906.

Among the first services to appear in prairie towns were general stores and post offices. Their impact went far beyond the bounds of the town itself. Those living and working in the surrounding region-- farmers, ranchers, loggers, and later oil field workers--relied on these services too, and frequently visited Okotoks to trade, send and receive mail, and purchase the necessities of life.

* * *

Mail came and went by train, so it's hardly surprising that the post office relocated right across the street from the station. To early settlers of Okotoks, it was a breathtaking revolution in the speed of communication. Now the settlers could cheaply send packages in a matter of days or weeks to their friends and family in Eastern Canada and the United Kingdom. Compare that to the expensive and months-long stagecoach mail that came before.

A telegraph line was laid early on too, giving the near instant communication we're used to today, though sending messages with it was expensive. Telephones wouldn't be introduced for another 20 years.

Regular mail service was an antidote to the oppressive isolation experienced by many of those early pioneers, especially those settled on rural homesteads. It also gave them access to consumer goods not available in the local general store or hardware store thanks to the burgeoning mail-order retailers.

Mail-order delivery is a business that has exploded in recent years with the rise of online giants like Amazon and Ebay, but it is by no means a new idea. In fact it was a key part of life for the prairie pioneers. Department stores like Eaton's, Simpson's, and Sears provided catalogues that covered every conceivable need, including clothes, cooking utensils, household appliances, and even entire prefabricated houses (some assembly required).

Gerardine Stewart, recalls how "shopping was conducted in a very different way in those days": "Articles were ordered from T. Eaton Co., Winnipeg, and Simpson's in Regina. Whoever in the community happened to be going to town stopped at each neighbor's house along the way and picked up the cream, eggs, grocery list and letter to the mail order companies. In town they took the cream and eggs to the creamery, cashed the cheque, but kept the stubs to show there was no cheating, picked up the groceries, sent the money orders and came back in the evening to drop off the proper items at the respective houses along with the correct change. This procedure was considered only ordinary neighborliness, in fact it was almost by way of an insult if the current traveller passed by the gate without stopping to shout, 'Want anything from town?'"2

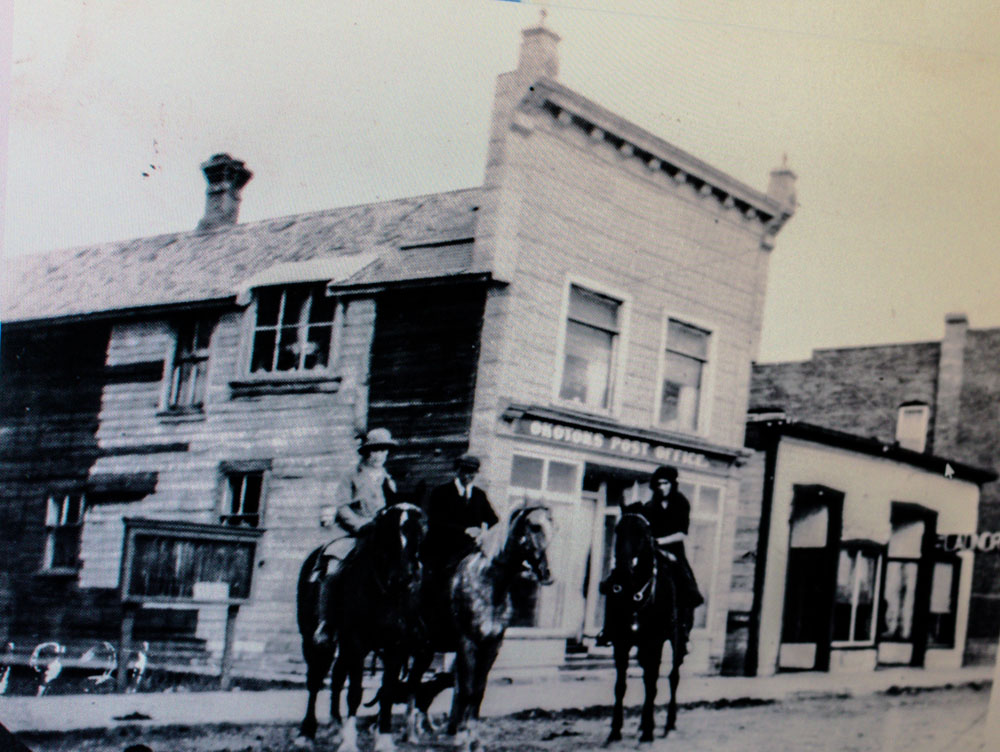

3. Making Ends Meet

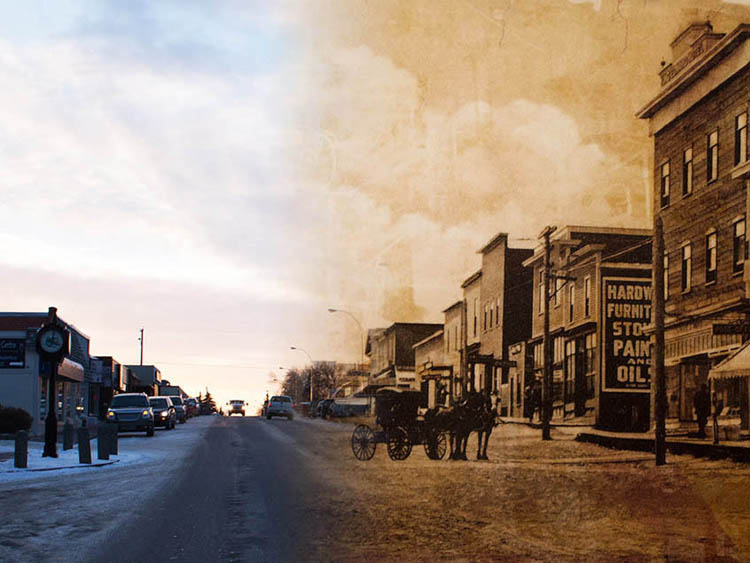

1906

North Railway Street was the heart of the commercial district in the early days. This photo shows the Paterson and Sons General Store, the Okotoks Post Office, Star Restaurant and Beattie Store (later Wentworth General Store), with several horse-drawn buggies parked on the street.

In the 1890s and early 1900s, Okotoks attracted many entrepreneurs who set up a diverse array of businesses to cater to the needs of the growing population. In a few short years the town boasted hardware stores, dry goods dealers, clothing stores, shoemakers, grocery stores, butchers, bakers, a watchmaker, and a barber--to name a few. And, of course, there were a whole range of businesses to serve the needs of local farmers such as blacksmith shops, harness makers and implement dealers.

* * *

The shopping experience was quite different from what most of us are used to today: A customer would present their shopping list to a clerk at the counter, who would gather everything up for them. This was an intensely social experience, and Jack Wentworth claimed to know 75 percent of his customers by their first name. An article about Wentworth's from 1961 waxed nostalgic about the decline of this style of shopping in favour of the customer wandering up and down the aisles: "Once you step inside and look along its shelf-bordered length of 140 feet, with the five clerks bustling about between counters, you realize how anti-social is the shopping cart."1

While businesses like Wentworth's General Store were able to continue largely unchanged for decades, other entrepreneurs were forced to creatively rebrand repeatedly in search of a market niche. One such entrepreneur was O.L. Pyatt, who established a barber shop and tobacco store in 1906 in the building located at 41 North Railway Street.

Pyatt was continually expanding his line of products and services to make ends meet. Within a year, he added public baths – 4 for a dollar – to his shop. He then added a bowling alley in an addition to the west. This venture didn’t catch on in Okotoks and he soon turned the bowling alley into a shooting range. Pyatt also operated a free employment office from his shop, matching those looking for work with farmers or businessmen needing labour.

Small town shopkeepers like Pyatt and Wentworth were known and fondly remembered by Okotokians at that time, and made a huge impact on their community.

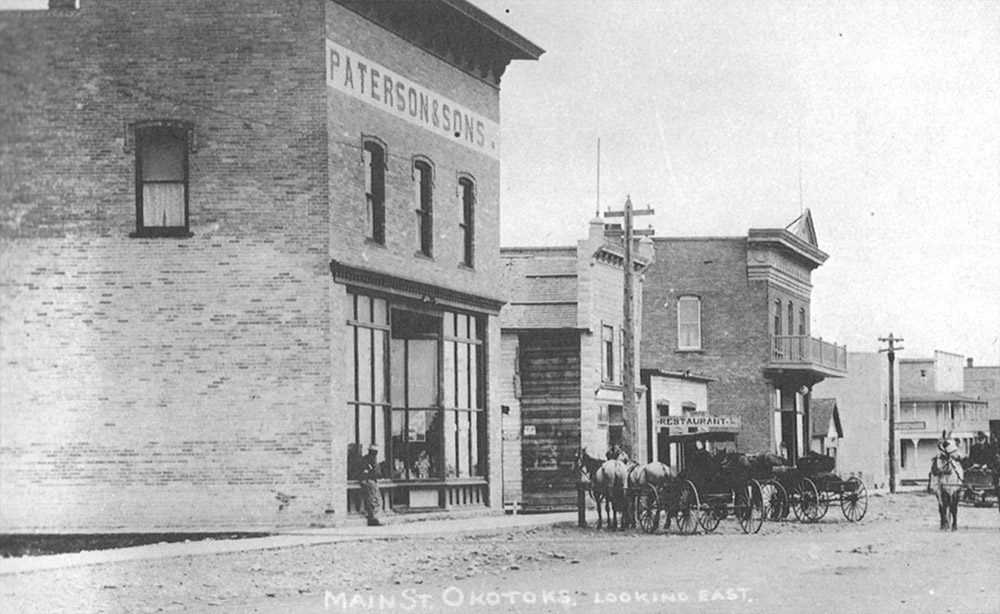

4. Building in Brick

1911

The Dutch photojournalist John Vanderpant stands in front of his photography studio that was located in this building, the McLeod Block.

In most Alberta towns, the first commercial buildings constructed were usually practical, inexpensive and made of wood. As soon as possible though, they were replaced by "substantial brick structures that reflected at once the affluence and the aspirations of their builders."1

These brick blocks didn't just confer prestige on the town, they were also less likely to burn down. This was an important consideration as fires were frequent, especially in Okotoks. According to one Okotoks resident "probably no Alberta town suffered more by fire."2

Unfortunately, even these brick buildings weren't entirely fireproof: one winter night in 1914 the Mcleod Block too went up in flames, taking Vanderpant's studio and possessions with it. As the unlucky man stood in the snow helplessly watching the fire consume his livelihood, he did what any good photojournalist would do and photographed the scene. These photos can be viewed in the app's Nearby section.

* * *

Okotokians were clearly swept up in the excitement. In 1907 the Okotoks Board of Trade released a booklet promoting investment and immigration to the town titled "Okotoks: the Eldorado of South Alberta." Eldorado, the mythical lost city of gold, was chosen as a nickname because of the apparently inexhaustible yields of golden wheat from the surrounding fields.

"Okotoks," it reads, "is about sixteen years old, and until the past five or six years did not show any unusual activity... With the advance of immigration, however, the brave little town took new life, and... has steadily but surely forged ahead to its present position, which warrants it in being confident of becoming one of the leading towns of Sunny Alberta."

The booklet extolls opportunities not just for new businesses, but for workers as well. "Okotoks offers good wages to labourers and tradesmen of almost any kind, laborers getting from $2.00 to $3.50 per day," or about $60 to $80 a day in today's money and skilled workmen $3.50 to $5.00. No need to be idle here. At least 300 men are needed now for quarry work, brickyards, building, lumbering, farming, railroads, construction, etc."4

It lists dozens of businesses established by local entrepreneurs, and boasts that "a large number of these men [at the time most entrepreneurs were men] occupy brick buildings, which testify to the substantial character of the town."5 The McLeod Block was one such building.

5. Prairie Banks

1912

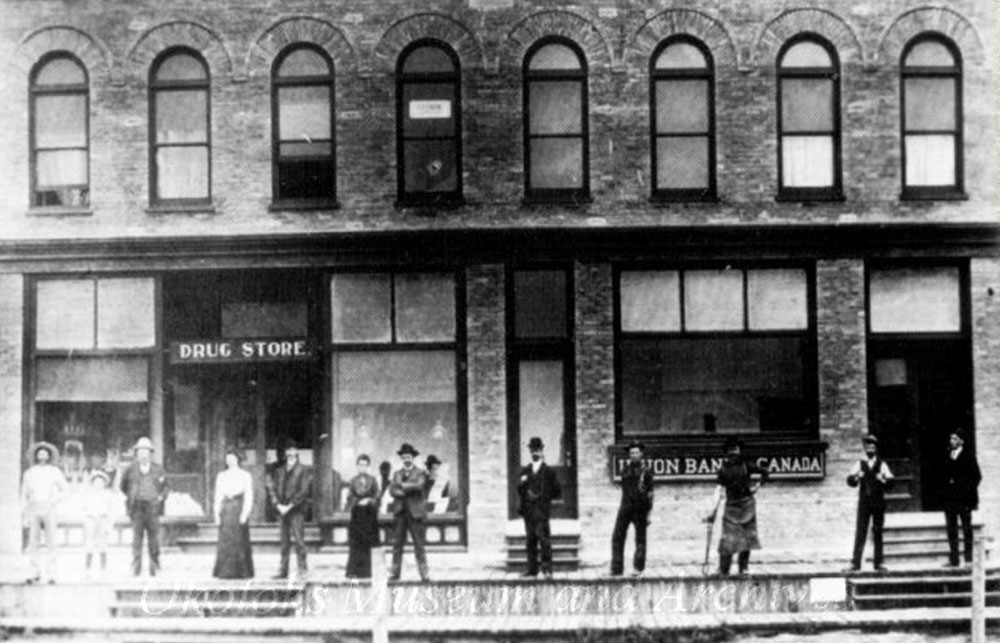

This photo shows local notables standing in front of the Stockton Block on McRae Street. They include John Lineham, widely known as the 'Father of Okotoks' (third from left), and Dr. Fred Stockton, the town's first doctor and mayor, and for whom the building is named (left of centre with arms crossed). The Block was completed in 1903 and housed Dr. Stockton's medical practice, a drug store, and Okotoks’ only bank at the time, the Union Bank.

As in most prairie towns in this period, the Union Bank played an essential role in the community's survival by making capital from Eastern Canada available to local entrepreneurs and new immigrants. Credit extended by the Union Bank was especially crucial to the survival of local farmers and ranchers, who were often a drought or an early frost away from financial ruin.

This economic system delivered prosperity in the good years, but its near total dependence on investors from outside Alberta was a great weakness -- as Okotokians discovered during the Great Depression.

* * *

They extended low interest loans to entrepreneurs, allowing them to jumpstart all sorts of new businesses. Once these businesses were established, the entrepreneurs might take out new loans to expand, which might draw more people to the community looking for work, who might take out loans of their own to start their own businesses, starting the cycle anew.

This business model was extremely effective in the years of the Western Canadian boom before World War I, when Okotoks grew from a few dozen inhabitants to at least 500.1 However, during economic downturns, the prairie banks became the sole lifeline that separated many businesses and farmers from financial ruin.

This was especially important in Okotoks, since it "had an exceedingly vulnerable economic infrastructure," that depended on a continuous influx of outside capital. As the historian Lewis G. Thomas states, "its industries, its lumber mill, the flourishing brickworks at Sandstone... all depended upon a buoyant construction industry."2

If a business or farmer had a bad year or two, then the bank could step in and loan them enough money to get back on their feet. But what would happen if the flow of outside investment froze up and the bank itself ran out of money? Then Okotoks would be in deep trouble.

That happened with the outbreak of the First World War. The Union Bank was funded by investors in Eastern Canada and the United Kingdom, and they quickly redirected their funds to the war effort, depriving Okotoks farmers and townsfolk of desperately needed credit. Five years of war came close to bankrupting both Canada and the British Empire. When the conflict finally came to an end, the economic damage to Okotoks was substantial--to say nothing of the human toll.

Thomas surveyed the damage: "The Okotoks of 1920 was a shadow of the optimistic and bustling town of the first decade [of the 1900s]." He continued: "The lumber mill had closed, the brickworks at Sandstone was falling into decay. No one worked the quarries. The flour mill survived for a time, but it was not rebuilt after its destruction by fire. There was one doctor where there had been three... Many of the stores had closed, especially those that had attempted a specialized trade. The skating rink, the most ambitious civic enterprise of the pre-war years, still stood but even its roof soon collapsed under the weight of an exceptionally heavy snow."3

The town's fortunes slowly recovered through the 1920s, thanks in part to ongoing development of the Turner Valley oil fields, but any optimism was short-lived. The Great Depression of the 1930s was coupled in southern Alberta with a historically unprecedented drought known as the Dust Bowl. Farmers had to watch helplessly as fierce winds blew away their parched topsoil--and by extension their livelihoods.

Gladys Bird graduated from high school in Okotoks during the 'dirty thirties', and recalled how "there were no government or bank loans or grants for anything." She had dreams to become a school teacher, but she "and many others had to give up our hopes and find whatever employment was available."4

Gladys succeeded in landing a clerk job, but many others were not so lucky: "Those looking for work had to travel by 'riding the rails' on freight cars, eating and sleeping in the 'jungles' of the dump yards or gravel pits, or in whatever shelter they could find. If they could not find work, they would chop wood or do some other small job in return for a meal or a lunch, or simply beg for something to eat."

The Depression made many realize how precarious life could become if banks and the financial system they represented were all that determined whether people in a town like Okotoks would be prosperous or impoverished. Caving to popular pressure, both federal and provincial governments finally responded by dramatically expanding their role in the economy, and creating a social welfare system to shield Canadians from the worst excesses of the free market.

6. The Oil Age

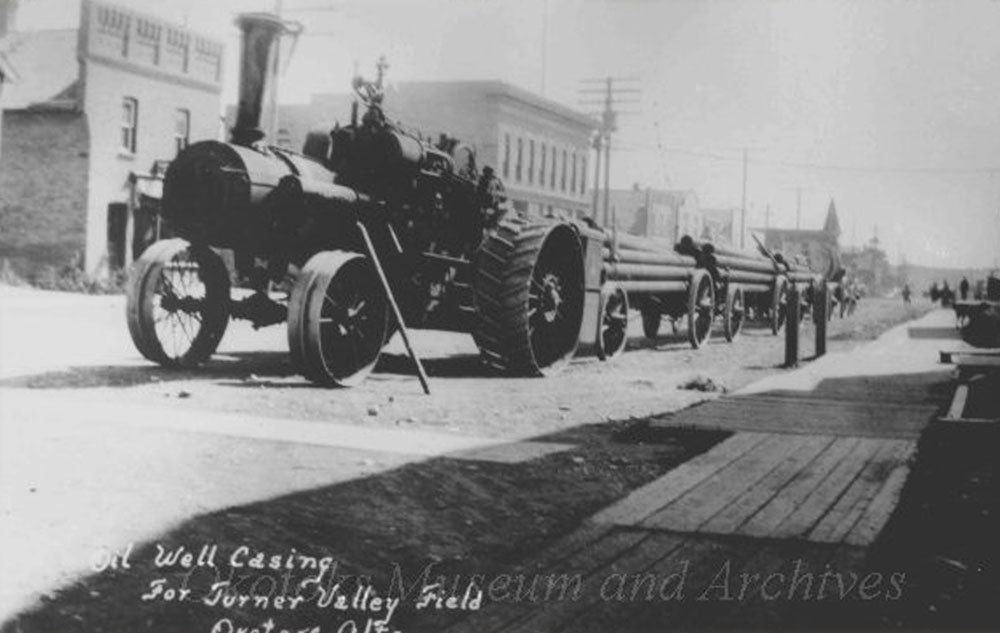

1914

A steam tractor on McRae Street pulls four wagons laden with steel casings bound for the oil and gas fields in Turner Valley.

The 1914 discovery of oil and gas in Turner Valley, about 20 km west of Okotoks, was a momentous event in the province's history, inaugurating the 'Turner Valley Era' of Alberta's petroleum industry. It all started when William Stewart Herron, an Okotoks rancher, discovered a gas seep on the banks of the Sheep River. Exploratory drilling began soon after, and on May 14, they hit black gold. For the next 30 years Turner Valley would be the most productive oil and gas field in the British Empire.1

Okotoks had the nearest railway station to Turner Valley, and so became the staging ground for development of the field. Several oil well supply stores set up shop in Okotoks as well as a customs office to handle the daily delivery of equipment shipped by rail from the United States. Soon after the discovery, Okotoks was crowded with oil workers and businessmen, and shipments of equipment like the one in this photo were a regular sight.

* * *

In August 1903 the first automobile was seen in Alberta, and it was considered a strong enough novelty to be worthy of news coverage. The Eye Opener, a newspaper which Bob Edwards first started in High River before relocating it to Calgary, took a dig at Okotoks by writing: "Billy Cochrane of High River has introduced the first automobile into Alberta. High River is the pioneer of progress. Okotoks still clings to the Red River cart."2

Okotoks wouldn't stay a laggard for long in this economic and technological revolution. Instead, she soon found herself thrust to the centre of it.

William Stewart Herron was born in Ontario in 1870, and spent some time in Pennsylvania's oil fields where he developed an interest in petroleum geology. In 1905, Herron and his wife purchased a ranch near Okotoks and started a variety of small business ventures. He investigated some gas seeps along the Sheep Creek near Black Diamond, and believed they hinted at a substantial oil and gas field beneath the surface. He began buying up the surrounding land and approached Calgary financiers and oilmen to partner with him.

The result was the formation of the Calgary Petroleum Products Company in 1911, "the first corporate entity capable of investigating petroleum prospects in the Alberta foothills."3

Drilling began in 1913, and continued for a long time with little success. Then on May 14, 1914, a new era in Alberta's development began. "Oil Shoots Sixty Feet in the Air," read the excited headline of the Red Deer News. "Flow so great that drillers have to suspend operations."4 "A frenzy of speculation immediately overtook Calgary," writes one historian. "Working out of makeshift brokerage offices, promoters hawked the dozens of new oil companies that had sprung up."5

Okotoks too transformed radically overnight, and the streets filled with equipment and oil workers making the trek to Turner Valley. Unfortunately this boom was short-lived; three months later the First World War started, and Canadian society radically reorientated its priorities from economic growth to total war, and the development of the Turner Valley oil fields ground to an almost complete halt.

After the war, drilling in Turner Valley slowly ticked up again. "Although this was good for business in [Okotoks] and provided employment for its young men, and husbands of some of its young women, it offered nothing like the stimulus provided to Alberta by the Leduc discoveries of 1947."6

Nevertheless, Turner Valley was the first significant producing oil field in Alberta, and Okotoks played an important part in that story.

7. Remittance Men

1905

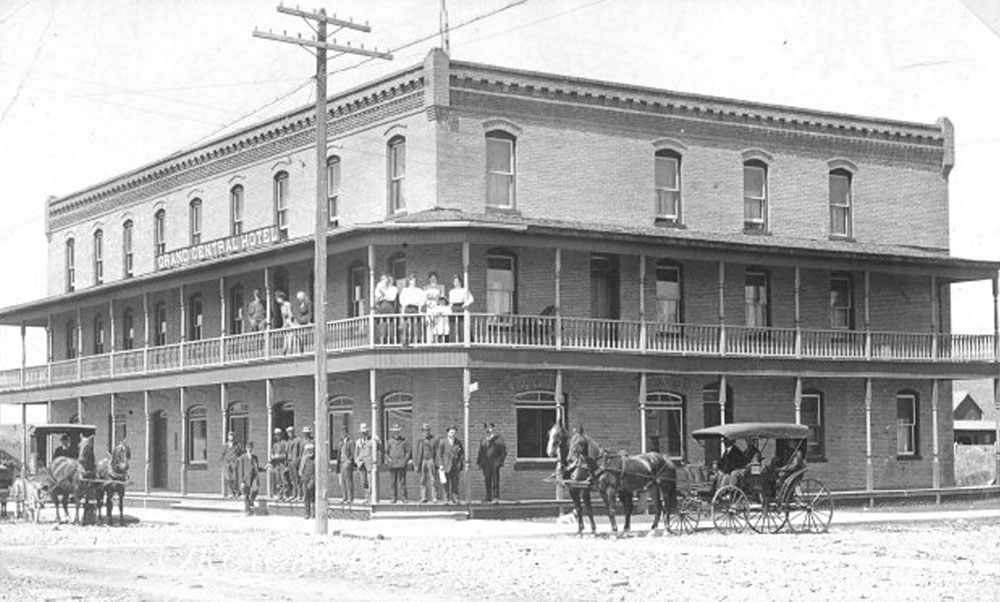

Here we see the Grand Central Hotel with a variety of men and women who have stopped to pose for a photo to celebrate its opening. When this hotel opened in 1905 it boasted top-of-the-line amenities, including over 40 rooms, a large dining room, billiard room, bar, and a showroom for salesmen to show off their wares. The hotel proved so popular that a large expansion was needed just a year after opening.1 The success of the Grand Central helped shift the town's commercial centre a few blocks west from the area around the station. The hotel was torn down in 1928 and replaced by the Willingdon Hotel, now known as the Royal Duke.

In those early days, hotels played an important role in the community: after all, the first two businesses in the Okotoks area were stopping houses. Many people in Alberta were transient, as the book Century of Memories explains: “There were steady boarders and many people stopped overnight or just for a meal. Many rested on their way to a new home.”4 One such boarder was Dr. A. E. Ardiel, who briefly took advantage of the hotel and its convenient stables to ride about making house calls.

* * *

After a big night at the Grand Central's bar, a man given the pseudonym Mr. Smith reached his limit, and had to be taken to bed. Unfortunately he was a loyal boarder at one of the other hotels and refused to spend the night at the Grand Central. So he was put in a wheelbarrow and taken to his favourite hotel, where he slept it off in the lobby. Only in the morning did he discover he had forgotten his false teeth at the Grand Central, much to everyone's amusement.3

The bars were also frequented by an all but forgotten character from this period of Canadian history: the remittance man.

In the British aristocracy it was always the oldest son who inherited and ran a family's estate. This often left the younger sons with a lot of money and little to do, a potentially embarrassing and troublesome combination. Parents often "found it more convenient to ship them off to some remote space in the colonies and maintain them there than attempt to curb their perverse ways at home."4 Since many of these men were raised on romantic notions of the Wild West, severral decided to move to Alberta to become cowboys.

The land around Okotoks was perfect for raising horses, so a number of remittance men bought ranches in the area and tried to make a go of it. After a hard days work on the ranch, they'd often appear in the hotel bars in full cowboy regalia which struck an odd contrast with their stuffy upper class English accents. Unfortunately it quickly became evident that they were "often well educated by English standards, but quite helpless when it came to life in the Canadian West."5

Okotoks resident Bernice Barrett recalls how these remittance men--"often the problem sons of rich families"--could be found in the Grand Central's bar. "Some of these men had land in the foothills and came to town for company. One wrote home to say he was doing fine, and that he had a ranch with two thousands head of gophers." Perhaps two thousand gophers (and no horses) sounded like an impressive accomplishment to an English earl who had no idea what a ranch was.6

Fortunately for the remittance men, failure at ranching could be remedied by writing home and requesting more money--remittances--from their blue-blooded families.

The remittance men became the butt of many jokes and a part of early Alberta humour, but as the 20th Century wore on they blended into Alberta society, and memory of them has faded.

8. The Lineham Sawmill

1892-1916

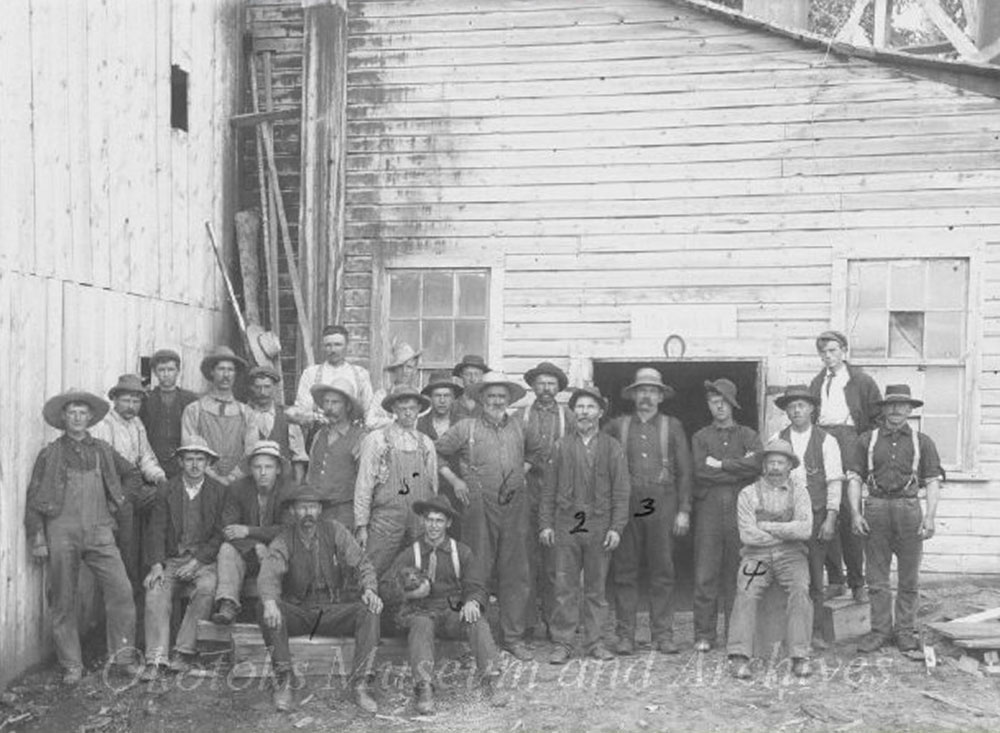

The Lineham Lumber Company sawmill operated from 1892 to 1916, and was the town's first major industry. It would put Okotoks on the map and draw in more workers to the fledgling village. The mill was located where the Okotoks Library is today. Established by John Lineham, the company was the main employer in Okotoks for almost 25 years. Lineham’s sawmill and logging camps provided work for over 100 men, producing about 30,000 board feet a day.1 Along with being Okotoks top employer, John Lineham was active in politics and served two terms as mayor, beginning in 1909.2

* * *

Being a lumberjack, log driver, or a labourer at the sawmill was dangerous work: “Injury and death could occur at any time and in myriad forms, including being hit by a wayward tree or infamous widow-maker (i.e., a broken limb hanging freely in a tree), or being crushed by a log that unexpectedly fell from its pile.”3

Unfortunately the First World War's economic impact, coupled with a devastating flood in 1915, put an end to Lineham's sawmill. It closed in 1916 and the site sat vacant until 1929 when a new ice arena was built.

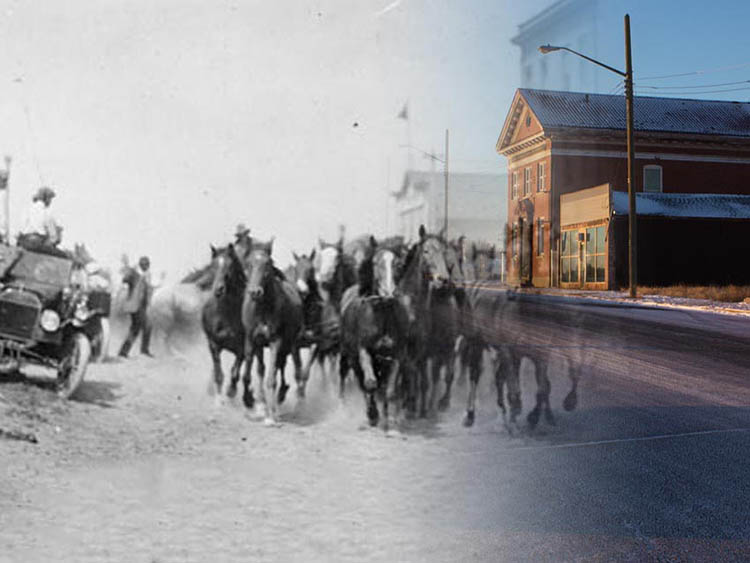

9. Bushels and Thoroughbreds

A 1990s freight train passes by Okotoks’ elevator row, a daily occurrence throughout much of the town’s history. The grain elevators once dominated its skyline, a towering reminder of the important role farming played in the local economy.

As a brochure produced by the Okotoks Board of Trade in 1907 claimed, "Okotoks is the centre of one of the most fertile stretches in the West. Nowhere is the rich, black loam more productive, and nowhere is the climate more temperate in the winter months." The land was so fertile that the District's farmers in 1906 achieved remarkable yields of 40 bushels of wheat per acre on average.1 Today, after a century of technological and agricultural advancement, Alberta's average per acre wheat yields have only marginally improved to 50 bushels.2

But farming wasn't the only thing that made Okotoks noteworthy: "If there is any one thing for which the District of Okotoks can justly and proudly claim the palm from the whole of Western Canada, it is for her horses--not one kind but for all kinds."3

* * *

Much of the district's most productive farms were to the east of town, and in those days farmers relied heavily on their horses; first to pull the ploughs in the fields and then to pull the wagon loads of grain to market. Everyone needed horses.

It's no surprise then that horse-breeding would become important here. In fact Okotoks played a central role in the development of Alberta's equine industry.

In 1885 a group of English gentlemen with a taste for fine horses and fox-hunting purchased a mammoth 66,000-acre parcel of land just west of Okotoks, calling it the Quorn Ranch.4 They wanted to breed the finest horses in the world and sell them to the British Army.

They certainly picked good land on which to do it. In 1887, Canada's chief veterinary inspector visited the area and was deeply impressed, writing "Probably no better horse-breeding country exists in the British Empire than the district of Alberta."5

The Quorn Ranch started importing "super-quality" thoroughbred stallions from England. One named Eaglesplume "became one of the most well-known early names in western thoroughbred racing and breeding history." Eaglesplume sired May W in 1894, who has since been considered "the greatest thoroughbred raised in Canada."6

The obsession with quality on the Quorn Ranch even extended to the "specially imported long-legged hunting hounds," though, as there were no foxes in Alberta, the ranch's guests had to make do with hunting coyotes.7

The Quorn maintained a focus on entertaining upper class English guests and remittance men, who "came west to 'do' a season on the range and learn about ranching--preferably in the comfort of a good chair on the manager's verandah. Entertaining these visitors in the elaborate fashion to which they were accustomed was a drain on the ranch's resources."8

In the end the British Army didn't end up buying the Quorn's horses, and the ranch struggled financially; in 1906 the entire enterprise collapsed.

Nevertheless the Quorn Ranch had established the district's impeccable reputation for horse-breeding. Many other breeders set up ranches in the area, drawing from the high quality stock left by the Quorn, and raising horses not just for racing and hunting, but freighting and farm work. In 1906 horses from the Okotoks area won two-thirds of the prizes at the Calgary Stallion Show.9 Ironically, during World War I, the British, French and Canadian armies later purchased numerous horses from Okotoks area ranches and shipped them overseas -- many with lineages to the Quorn breeding stock.

The horse's role on the prairies was changing as cars, trucks, and tractors replaced many of their functions. "The gentlemanly settlers" who ran the horse ranches "were still gratifying this passion for horseflesh in the 1920s and 1930s in spite of the painful indications that they were waging a losing fight against the realities of the marketplace."10

Today horse-breeding still occurs on a small scale in the Okotoks district, and farming remains an important part of the economy, but its importance has been eclipsed by other sectors.

The last grain elevator was torn down in Okotoks in 1995 and the seed-cleaning plant, also located on elevator row, was destroyed by fire in 2012. The empty plot of land where the grain elevators once stood is a solitary reminder of Okotoks’ economic evolution over the past century.

10. The Changing Economy

A hardworking crew at Lineham's sawmill poses for a portrait in front of the main mill building that once stood where the library stands today. Okotoks has come a long way in the century since this photo was taken. After the Second World War the town's population stabilized around 800, but the dramatically increasing popularity of cars had several effects: People could easily commute from Okotoks to their jobs in Calgary, and also to job sites on the outskirts of town.

* * *

A significant event was the connection of Okotoks to Calgary by a new highway in 1954. This modern development meant a faster, smoother drive to the city by Okotoks residents. It also meant an influx of Calgarians settling in Okotoks and driving to work every day. However, the new long distance commuters perturbed some Okotoks’ municipal leaders: "Town officials continue to encourage local industry lest the community be dubbed 'The Bedroom of Calgary.'"1

Their plan for local industry quickly bore fruit. In 1959 the Texas Gulf sulphur plant opened just east of downtown, employing 45 people. Mocoat Fibre Glass was another major employer that followed in the 1970s.

When the Town of Okotoks celebrated its 100th birthday in 2004, the population stood at 12,187, a gigantic leap from just a few decades before. Since then it has remained one of the fastest growing communities in Canada, and had more than doubled its population by 2014, to 27,331.2

In the early days, Elma Street, parts of McRae Street and Elizabeth Street, as well as south of the railway tracks, were the primary residential areas of the community. Since then, most residents have moved into rapidly expanding suburbs north of downtown, and to the south side of the Sheep River. Likewise, in the pioneer era, both the commercial and industrial heartlands of town were centralized in the historic downtown; they've both now moved. Large commercial centres have established south of the river, while the industrial park is located on the east side of town.

Yet despite the economic changes, the fires, and the ravages of time, many heritage buildings in the downtown core have been well preserved, and the area continues to provide a vibrant place to shop, work and live.

Endnotes

1. Okotoks Gets Its Start

1. Lewis G. Thomas, "Okotoks: From Trading Post to Suburb," Urban History Review. Vol 8: No 2, October 1979, 9.

2. Okotoks and District Historical Society, A Century of Memories: Okotoks and District, 1883-1983 (Okotoks: Okotoks and District Historical Society, 1983), 6.

3. Thomas, 10.

4. Krista Conrad, "Rail played integral role in Okotoks history," Okotoks Today. May 16, 2018, online.

5. Okotoks Board of Trade, Okotoks: The Eldorado of South Alberta, (Calgary: Hammond Lithographing Company, 1907), 5.

2. The Postal Service

1. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 6.

2. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 238.

3. Making Ends Meet

1. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 668.

4. Building in Brick

1. Thomas, 12.

2. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 2.

3. Thomas, 10.

4. Okotoks Board of Trade, 5.

5. Okotoks Board of Trade, 8.

5. Prairie Banks

1. Thomas, 12.

2. Thomas, 11.

3. Thomas, 13.

4. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 113.

6. The Oil Age

1. Town of Turner Valley, "Turner Valley Gas Plant," turnervalley.ca, online.

2. James G. MacGregor, A History of Alberta: Revised Edition, (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1981), 180.

3. David Breen, "Heron, William Stewart," Dictionary of Canadian Biography, online.

4. Red Deer News, "OIL STRUCK AT CALGARY," May 20, 1914, page 4, online.

5. Breen, online.

6. Thomas, 13.

7. Remittance Men

1. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 12.

2. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 13.

3. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 14.

4. Loretta Faith Balisch, "Scrub Growth: Canadian Humour to 1912--An Exploration," Graduate Thesis, (St. John's: Memorial University, 1994), 374.

5. Balisch, 375.

6. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 13.

8. The Lineham Sawmill

1. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 6.

2. Henry Klassen, "Lineham, John," Dictionary of Canadian Biography, online.

3. Mark Kuhlberg. "Lumberjacks," The Canadian Encyclopedia, online.

9. Bushels and Thoroughbreds

1. Okotoks Board of Trade, 5.

2. Statistics Canada, "Production of principal field crops, July 2019," online.

3. Okotoks Board of Trade, 20.

4. Edward Brado, Cattle Kingdom: Early Ranching in Alberta, (Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2004), 136.

5. John Blue, Alberta, Past and Present, Historical and Biographical, (1924), online.

6. Lindsay Ward, "The Early Days of the thoroughbred in Southern Alberta," Canadian Thoroughbred Magazine. March 3, 2017, online.

7. Brado, 138.

8. Brado, 138.

9. Okotoks Board of Trade, 16.

10. Thomas, 10.

10. The Changing Economy

1. "Our Historic Past," Town of Okotoks, online.

2. Town of Okotoks.

Bibliography

Balisch, Loretta Faith. "Scrub Growth: Canadian Humour to 1912--An Exploration." Graduate Thesis. St. John's: Memorial University, 1994. https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk3/ftp04/NQ36198.pdf

Blue, John. Alberta, Past and Present, Historical and Biographical. 1924. https://www.electricscotland.com/history/canada/alberta/vol1chap19.htm

Brado, Edward. Cattle Kingdom: Early Ranching in Alberta. Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2004.

Breen, David. "Heron, William Stewart," Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Conrad, Krista. "Rail played integral role in Okotoks history," Okotoks Today. May 16, 2018. https://www.okotokstoday.ca/local-news/rail-played-integral-role-in-okotoks-history-1536020

Klassen, Henry. "Lineham, John." Dictionary of Canadian Biography. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lineham_john_14E.html

Kuhlberg, Mark. "Lumberjacks." The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Okotoks Board of Trade. Okotoks: The Eldorado of South Alberta, Calgary: Hammond Lithographing Company, 1907. http://contentdm.ucalgary.ca/digital/collection/p22007coll8/id/1074832

Okotoks and District Historical Society. A Century of Memories: Okotoks and District, 1883-1983. Okotoks: Okotoks and District Historical Society, 1983.

Thomas, Lewis G. "Okotoks: From Trading Post to Suburb," Urban History Review. Vol 8: No 2, October 1979, pp. 3-22. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/uhr/1979-v8-n2-uhr0895/1019375ar.pdf

Town of Turner Valley. "Turner Valley Gas Plant," turnervalley.ca. https://turnervalley.ca/visit/turner-valley-gas-plant/

Town of Okotoks. "Our Historic Past," okotoks.ca. https://www.okotoks.ca/culture-heritage/museum-archives/our-historic-past

MacGregor, James G. A History of Alberta: Revised Edition. Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1981.

Red Deer News. "OIL STRUCK AT CALGARY," May 20, 1914, page 4. www.peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers

Statistics Canada. "Production of principal field crops, July 2019."

Ward, Lindsay. "The Early Days of the thoroughbred in Southern Alberta," Canadian Thoroughbred Magazine. March 3, 2017. https://canadianthoroughbred.com/magazine/miscellaneous/the-early-days-of-the-thoroughbred-in-southern-alberta/