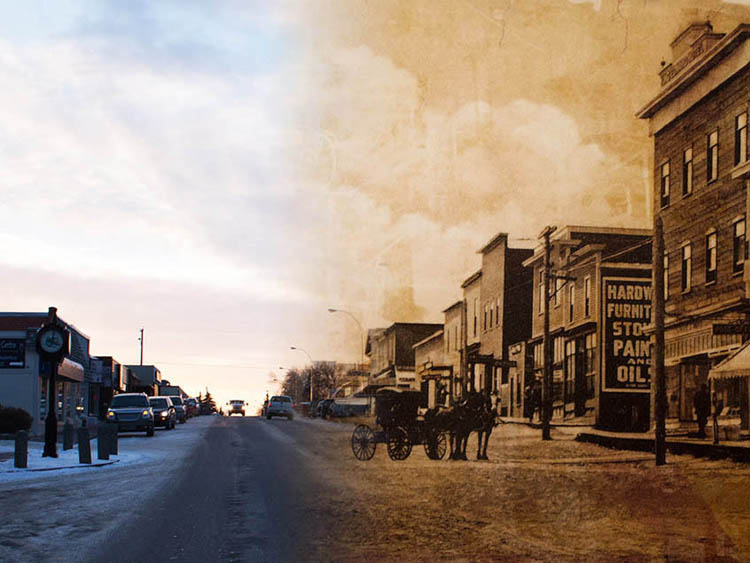

Walking Tour

The Sheep River

The Land and the People

Taylor Peacock, Elyse Abma-Bouma

The Sheep River has always been a crucial ecological landmark, not just for the residents of Okotoks, but for the Indigenous people that have lived on this land for thousands of years. Follow along as we take you on a tour along the banks of the Sheep River and learn about its ecology and history. We will see how people have relied on the river for thousands of years, and how it has shaped the lives of the citizens of Okotoks.

The tour starts at Southridge Drive, where we introduce the history of the Sheep River, and the importance of this river crossing to the Plains First Nations. From there, we travel along the Sheep River pathway, moving from the history of Indigenous land use to the changes brought about by the signing of Treaty 7 and the settling of Okotoks. Walking alongside the river, we'll see how the citizens of Okotoks relied on the river for work and recreation. Stops focus on the river's role in industry such as the sawmill; recreation such as swimming, and skating; and as a food source fishing and wild fruit. We conclude the tour the way it began, focusing on the Indigenous connection to the land. The last stop tells the story of the cottonwoods that line the banks of the Sheep River and their role as burial trees for the Blackfoot.

This project is a partnership with the Okotoks & District Historical Society. We also would like to thank the Ridge at Okotoks for sponsoring our work trip.

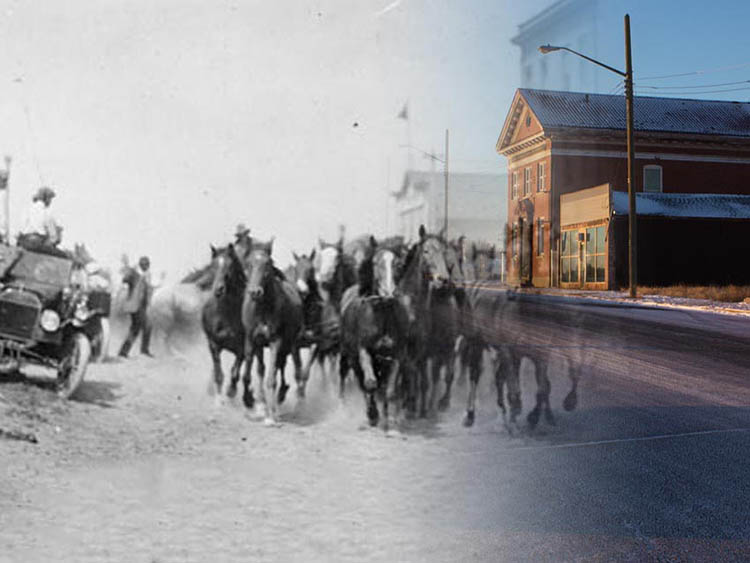

1. An Ancient Crossing

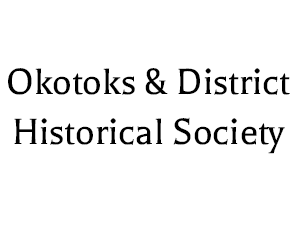

early 1900s

A view of the Sheep River and Okotoks beyond. The Blackfoot people called this river 'Eetookiap', their word for sheep, and a reference to the bighorn sheep found at the river's headwaters in the Rocky Mountains. This spot you're standing at now was a ford shallow enough for the great herds of bison to cross, followed by the Blackfoot. This ancient crossing later became known as the Macleod Trail -- the trail used by bull trains, stagecoaches and the Northwest Mounted Police -- which crossed the Sheep River at two locations -- one is near where you are standing; the second is further east near the train bridge.

* * *

For thousands of years before European colonization, Indigenous peoples including the Blackfoot (Siksika, Kainai, and Piikani), Cree and Stoney-Nakoda peoples lived a nomadic lifestyle that revolved around the great herds of bison. As they tracked the herds across the prairies, they followed them across two key fords along the Sheep River. One was located right on this spot, by the modern day Northridge traffic Bridge. We still travel the routes of the bison some 300 years later.

Finding one's way across the vast and often featureless expanses of prairie was no easy task, and the Indigenous peoples relied on the few natural landmarks to guide the way. One such landmark was a huge glacial erratic deposited about 8 km east of Okotoks during the last Ice Age. Weighing in at 16,500 tons, the Okotoks Big Rock, as it is now known, is the size of a three storey apartment building. In the Blackfoot language 'Okatok' means Rock.2 This glacial erratic is how the town of Okotoks got its name. Samuel Livingstone, a trader and adventurer, remembered killing his last bison about a mile north of the future town in 1879. After that they were gone.

For the Plains First Nations, the death of the bison herds meant catastrophic famine. Their society fatally weakened by hunger and European diseases, they came to the negotiating table with the young Canadian government. They were promised shared hunting lands, mutually beneficial trade agreements, and food, and so Chief Crow Foot signed Treaty 7 in 1877, confining his people to reserves while relinquishing their land and almost all their political and civil rights.

The Canadian Government did not intend to fulfill their obligations under the treaty--meagre as they were. During a House of Commons debate in 1882 about the cost of feeding the reserves, Father of Confederation Prime Minister John A. Macdonald stood and said "I have reason to believe that the agents as a whole … are doing all they can, by refusing food until the Indians are on the verge of starvation, to reduce the expense." Over a third of the Plains First Nations who resettled on the reservations died between 1880 and 1885.3

With the extinction of the bison and the removal of Indigenous peoples, European settlers made quick work of changing the landscape into a home for their families. In 1882, the first of the settlers had arrived, and the opening of the Lineham sawmill in 1891 saw the beginnings of the town taking shape.4

2. Sheep River Park

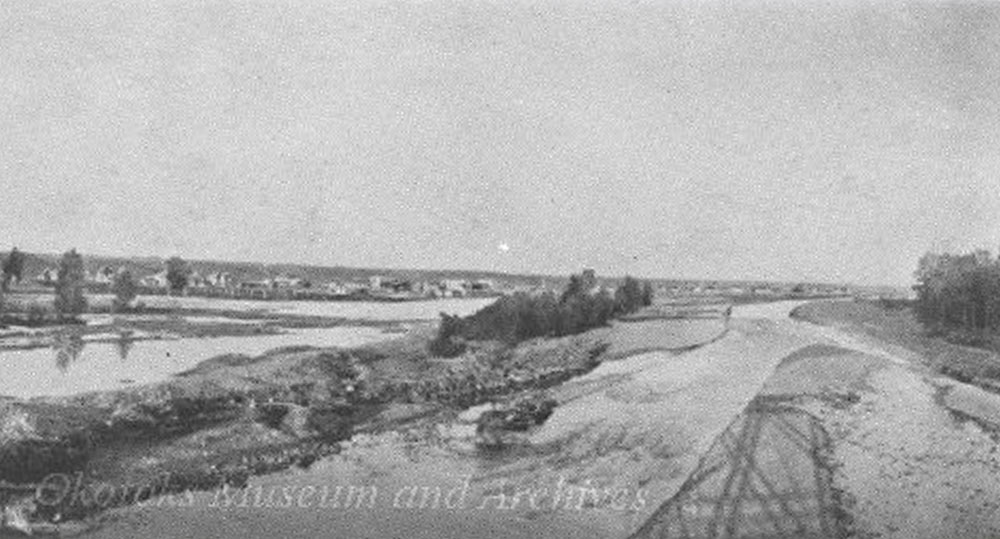

1920s

Dozens of cars fill the park along the Sheep River for a community picnic in this 1918 photo -- proof that not only did residents work hard, but they played hard.

* * *

3. We Made Our Own Fun

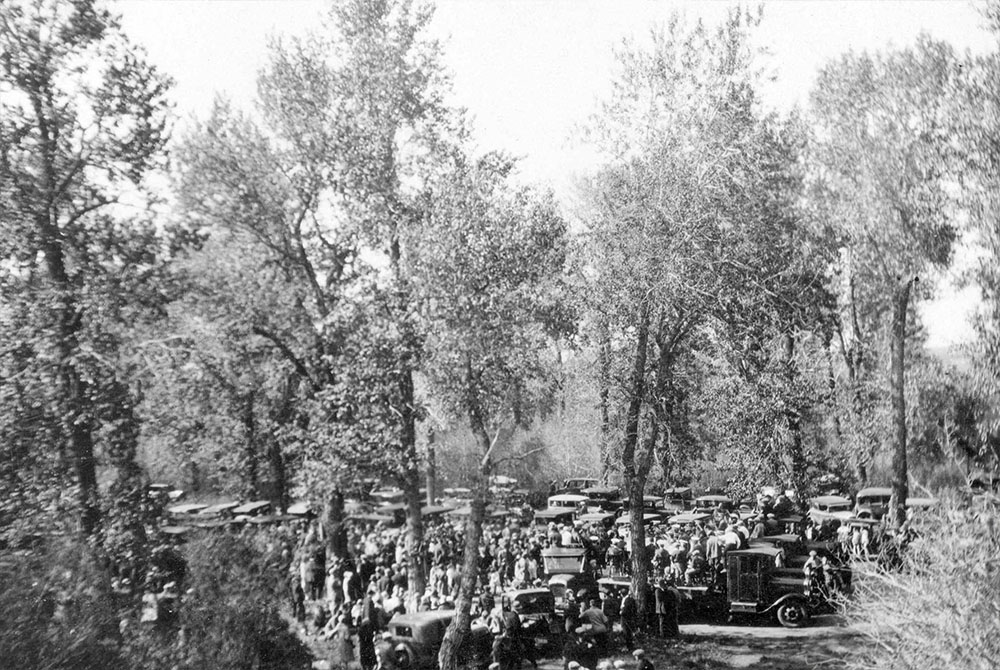

1963

A photo of the Sheep River at its spring high-water levels, overlooked by the McCabe elevator in the background. The same forces that drew the Indigenous peoples here also made it an attractive spot for European settlers, who would soon call it home and who would change the land forever. From the early days of settlement, the Sheep River was the town's focal point. Not only was it an important economic tool, but it was also a spot for fun and recreation.

* * *

While leisure activities such as swimming have not changed since those days, what we wore has. In the early part of the 20th century, women's bathing costumes covered almost the entire body. Immodesty was a finable offence.

In Okotoks, the immodesty of swimmers in the Sheep River was so common that it made the local newspaper. The Okotoks Observer on August 6, 1914 issued the following warning: "All this summer, bathers both men and women have been taking advantage of the cool pools in Sheep Creek and there has possibly been far more swimming than ever before. But many have appeared to disregard the fact that bathing suits are fashionable in certain sections of the globe and the RNWMP have intimated to The Observer that hereafter a charge of indecent exposure will be laid, and pressed, against anyone, man, woman or child, caught bathing while unprovided with a proper and sufficient bathing costume."1

Swimming was so popular in Okotoks that in the 1950s, the town council brought in truckloads of sand to create a public beach on the banks directly opposite where we are standing. The town even hired a lifeguard to patrol the beach and river in the area. That soon ended due to flood waters washing away the beach.

In the colder months, skating was a popular pastime. Evelyn Johnson comments on the thrill of skating on the river: "We used to go and tell our parents we were going skating on a Sunday afternoon. We'd go down the river and skate to Black Diamond and back. I can remember coasting across and hearing it hollow underneath. They never knew that. The river was deeper, but you wouldn't drown. You might get wet, but I don't think you'd get drowned… at least I hope not!"2

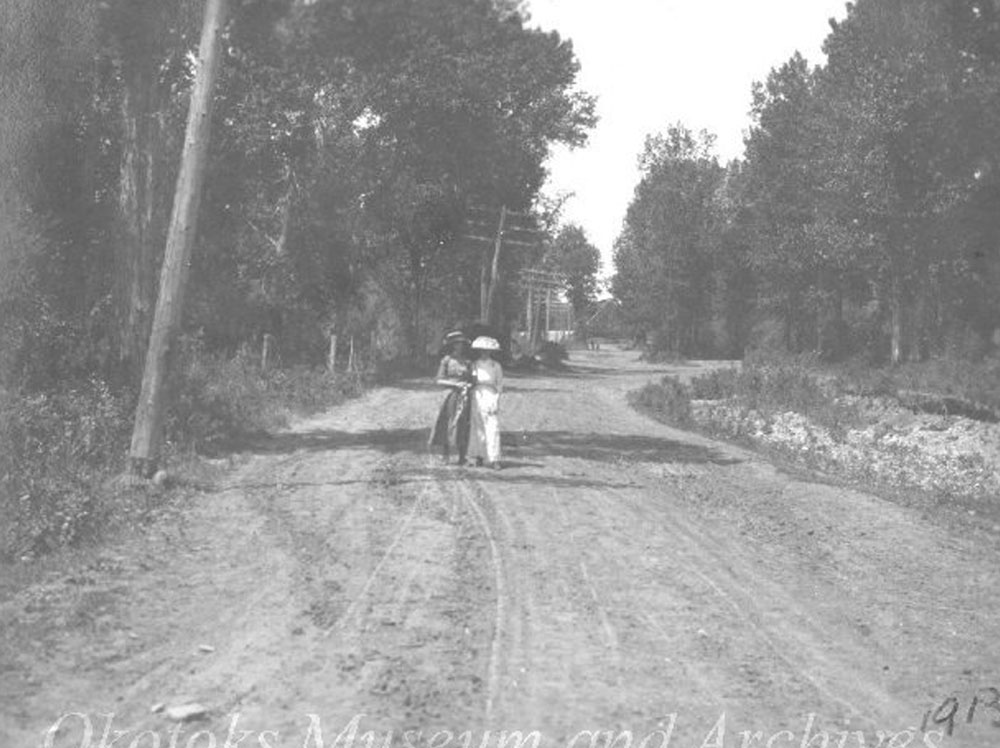

4. Walking the Riverbank

1913

The above photo shows two women taking a stroll on a tree-lined trail in Sheep River Park, with wide-brimmed hats and dresses protecting them from the sun. Even while enjoying leisurely pastimes, women were expected to dress appropriately.

* * *

It was not until the 1920s that women dared wear pants in public. Prior to that, women were expected to wear long sleeves and high boots so not even their ankles were showing. As a result, the hem of their dresses would have been a dusty mess after a day walking though Sheep River Park.

5. The Log Drivers

1912

This photo shows Mary Daggett sitting atop a post alongside the mill pond of Lineham Lumber Company. The pond is filled with logs that have been floated down during the annual spring log drive, awaiting processing in the mill. While the river was essential to Okotoks as a source of clean water, it also played a crucial role in transporting logs felled in the foothills upriver. The Lineham sawmiill established on this spot in 1891 was the lynchpin of the town's early economy.

* * *

In Okotoks, preparations for the logging season began in late fall, when the river froze and the loggers built their camps in the mountains. Once winter arrived, they would begin felling trees, continuing until the first thaw in early spring. When the river completely thawed, teams of drivers would begin the arduous six-week log drive down the Sheep River towards the mill at Okotoks.

Elma Lineham recorded a history of the logging industry in Okotoks in the local history book. She was the daughter of John Lineham, founder of the Lineham Mill, and widely considered the Father of Okotoks. "My Father obtained timber rights on the Sheep Creek River and the Highwood River and established lumber mills in Okotoks and High River in 1891-92. Lineham Lumber Company mill was completed in 1891, the first big run of logs came down in 1892. Lumbering was the main industry in Okotoks for the next twenty-five years... My sister Bess and I used to be taken up to these camps by my Father and the Chinese cook put on a real feast for the 'Boss's girls.' It was fun watching the log jams being sent on their way. The lumberjacks worked with caulked boots and peevies - it was interesting seeing how agile they were, leaping from the moving logs…”2

Log driving required men with elevated balance and agility as they hopped from one bobbing and rolling log to the next. People loved to watch the drivers in action, and Dallas Wright recalls how "The log drive was an important event in the Spring of every year. Everyone went to the river to see this..."3

6. Learning to Fish

1912

In this photo Libbie Henderson is fishing in one of the shallow pools of the Sheep River. In the early settlements of Okotoks, one of the major draws of the river was the excellent fishing that could be found along the banks. The Sheep River continues to be a popular fishing destination today.

* * *

Jackie King recalled learning to fish here: "My brother Egerton Warren was born in Okotoks in 1919. Sheep Creek was a natural fishing hole and my brother learned the art of catching trout at an early age. His love for the sport has continued and he has caught many large fish in different parts of the world, but I venture to say that his early years were the most exciting. He would take me with him to the creek. Mr. Thompson would provide me with a hook from his hardware store; Egerton would cut a willow branch and with string from Mr. Hicks' store, I too became a fisherman."1

7. Childhood on the Riverbank

1910

A group of children gather for a birthday party along the banks of the Sheep River in the 1910s. Childhoods spent on the banks of the river are a common theme recorded in the Okotoks community history book, A Century of Memories.

For generations of kids in Okotoks, the river was their playground, and where most grew up swimming, skating and fishing.

* * *

While many of the residents recalled playing along the banks, others remember helping out on the farm, and driving herds of cattle over the river fords. "In the early thirties, Dad used to winter cattle from the foothills. It was mostly Walter Phillips stock from Kew. I usually trailed these cattle down in December, and took them back in the spring. There was always one old cow that would take the lead which would help to string them out, making the trailing easier. My sister Mildred would often meet me at Sheep Creek and help me across. Sometimes the river was frozen over and very slippery, so Dad would take the team and sleigh and scatter manure making the crossing easier. The cattle pastured on the stubble and straw stacks. In those days there was a lot of grain that went into the stacks when they threshed, which made the feed better than baled straw from the combines today. The stacks also made good shelter. It was my job to check the cattle regularly to see that they had water and salt and that all was well."2

8. A Lifeline in Hard Times

1917

School chums Ada Beaton and Willa Coultry stand next to the towering saskatoon bushes in full bloom along the Sheep River, in May of 1917. The berries would be ready to pick in July.

Many residents have clear memories of picking berries, whether it be chokecherries or saskatoons, both of which grew in abundance. Throughout the 20th century, children would pick berries for preservation, to be made into jams and preserves, or to be sold. Berry picking was not just the sole job of children, everyone in the community would pick berries, and they were critical in lean times.

* * *

During the Great Depression, when many families struggled to feed themselves, unemployment was high and crops were scarce. Saskatoon berries and other wild berries were a critical food source.

Ruth Hamilton remembers how many berries her family picked during those years:

"With the big depression in full swing all ways and means of putting food on the table were fully considered. We all picked saskatoons, Dad, Mom, Uncle Bill and us kids, by the washtub, boiler, milk buckets, and syrup pails full. Charlie and Thelma have to be the champion berry pickers of all time. 'Could they strip a tree!' One summer Mom put down nearly three hundred quarts of saskatoons. It seemed as though she spent most of the summer sitting on our shady veranda cleaning berries. It was a good way of socializing though, as every one who passed our gate stopped to visit or came and sat in the shade, and while chatting, cleaned a few berries..."2

Berry picking was also a way for children to make a little bit of pocket money. Rhoda Kopas's children would pick berries to help make enough to attend the Calgary stampede: 'The children walked two miles to school in all weather. The highlight of the year for the children was the Calgary Stampede. "The children walked two miles to school in all weather. The highlight of the year for the children was the Calgary Stampede. Through the year they collected gopher tails (2¢ each) and beer bottles along the highway. They picked saskatoons and raspberries, and any money they received as gifts was all pooled together and spent at the Stampede. Families would gather together by the river for a picnic lunch and the children were turned loose to enjoy themselves. All would meet later at the Ferris wheel." 3 In the early 1900s, a five pound pail was worth around 25 cents, about 3 dollars today, and children would horde their hard earned cash for sweets.4

During the Second World War when rationing once again squeezed food supplies, berries again became an important part of Okotokians' diets. Saskatoon berries acted as a natural sweetener in the absence of sugar, which was rationed to 200 grams per adult per week.5 While traditionally preserved as a jam with sugar, women across the country and at Okotoks learned to preserve berries without that critical ingredient.

"I remember the fall of 1942 being an exceptionally good berry year. The wild fruit trees were laden. Jack and Don Anderson picked saskatoons down near the railway bridge east of the town. They came home with a baby's zinc bath tub almost full of berries. It was in the war years then and sugar was rationed. The Canadian Western Natural Gas Company's home economics department instructed us homemakers on how to preserve the berries without using sugar or water. I canned so many saskatoons that I was making saskatoon pies years after the war was over and plenty of sugar was again available. The preserving method we had been taught during those war years was very successful."6

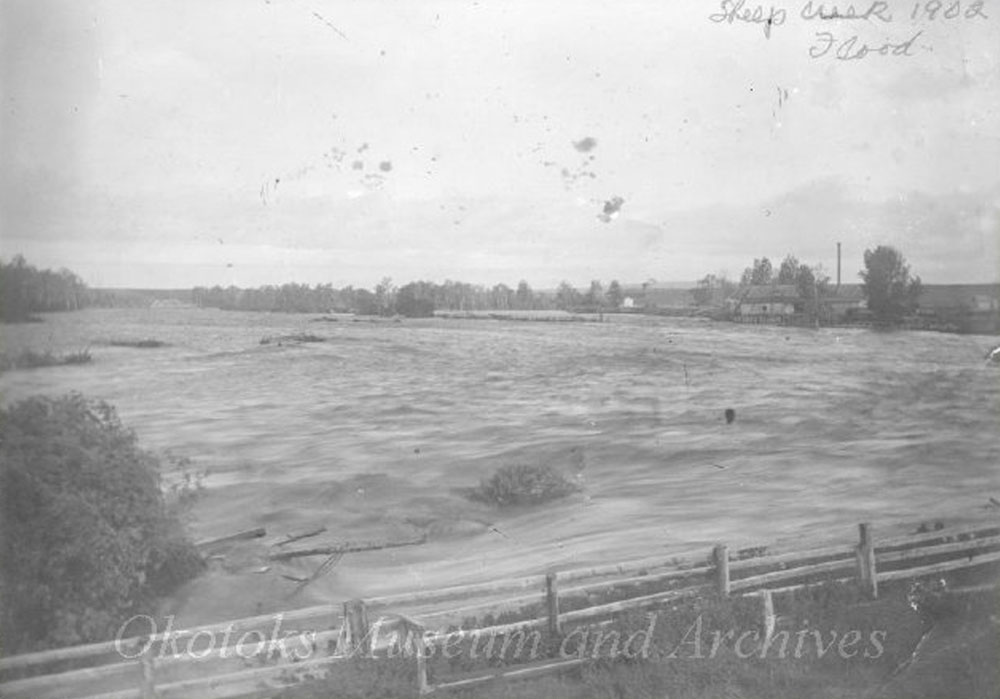

9. The Unpredictable River

1902

In the above picture, the 1902 flood has overtaken the banks of the river, and as you can see in the far right corner, come up to the side of the house. Throughout the history of Okotoks, the river has been a safe crossing space, a source of prosperity, a lifeline in times of hardship, and a danger not to be taken lightly.

For all the benefits the Sheep River provided, it was not without its dangers. Flooding was--and is--frequent, and severe floods have often wrought havoc on Okotoks.

* * *

In 1902, the flood destroyed the sole bridge over the river, leaving residents unable to cross. Many homes in the residential area along South Railway Street, just to the northeast of here, were damaged by that flood, including John Lineham's original home. Elma Lineham remembered the destruction of the family coop most clearly: "1902, I think, was the year of a very bad flood in both rivers. Our house in Okotoks was partly washed away. All the logs went down and had to be salvaged from as far away as the Little Bow River. We kids, our cousins - Minnie, Bill, baby George; and Bess and I were all locked up in Uncle Will Lineham's house which was on higher ground than ours. My most vivid memory was of our chicken house floating down the river with all the chickens on the ridgepole. The bridge over the river was washed out."1

The 1915 flood was similarly destructive, ripping up the sidewalks of the town and drowning a man. As a child, Ruth Hamilton recalled how the rapid rise of the waters caught them off guard: "Waking up in the dark of night with a foot of water in our bedroom. My Dad and Mom putting us kids, Charlie, Thelma and me under a tarp in the wagon and the horse splashing through the water on the way to Grandad Foran's farm, away from the flood."2

As the Okotoks Review wrote in 1915: "A relic of the flood is seen in the quantities of loose sidewalk floating around in the west end. The Council have put men to work however repairing and generally fixing things up, including the culvert beside the rink which was washed out. The road on the other aide of the new bridge was badly damaged and the park on both sides was under water." 4

Milicent Sanderman summed up how surprising the floods at Sheep River had been for the residents, when she recalled the 1932 flood: "Unless it is seen, it is almost impossible to imagine how our ever faithful Sheep Creek can flood."3

The floods have always been triggered by melting snow in the mountains, followed by rains that last for days. Such wet conditions mean that the river supersides the banks. Countermeasures such as sandbags, pumps, siphons, and filters can ameliorate the damage, but frequently there hasn't been enough advance warning to make them effective. Okotokians have had to learn how to rebuild and move forward.

Here at the end of our tour is a good time to stop and reflect on the long ancient history of this place, and the many generations who have been drawn here to the banks of the Sheep River.

Endnotes

1. An Ancient Crossing

1. Force, S.A.F.R.T., 2014. Southern Alberta Flood Recovery Task Force Flood Mitigation Measures for the Bow River, Elbow River and Oldman River Basins Volume 1–Summary Recommendations Report.

2. "Okotoks Erratic - 'Big Rock', Government of Alberta Website, online.

3. Okotoks and District Historical Society, A Century of Memories: Okotoks and District, 1883-1983 (Okotoks: Okotoks and District Historical Society, 1983), 6.

4. Tristin Hopper, "Here is what Sir John A. Macdonald did to Indigenous people," National Post, August 28, 2018.

3. We Made Our Own Fun

1. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 325.

2. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 282

4. Walking the Riverbank

1. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 135.

5. The Log Drivers

1. Graeme Wynn, "Timber Trade History," The Canadian Encyclopedia, July 26, 2013, online.

2. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 362.

3. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 641.

6. Learning to Fish

1. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 347.

7. Childhood on the Riverbank

1. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 153.

2. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 497.

8. A Lifeline in Hard Times

1. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 467.

2. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 331.

3. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 353.

4. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 339.

5. CBC Kids, "Did you know we had to ration food during the war?" online.

6. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 97.

9. The Unpredictable River

1. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 362.

2. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 332.

3. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 62-63.

4. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 62.

Bibliography

CBC Kids, "Did you know we had to ration food during the war?" https://www.cbc.ca/kidscbc2/the-feed/did-you-know-we-had-to-ration-food-during-the-war.

Hall, M.A. Immodest and Sensational: 150 Years of Canadian Women in Sports. James Lorimer & Company. 2008.

Tristin Hopper, "Here is what Sir John A. Macdonald did to Indigenous people," National Post, August 28, 2018. https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/here-is-what-sir-john-a-macdonald-did-to-indigenous-people

Okotoks and District Historical Society. A Century of Memories: Okotoks and District, 1883-1983. Okotoks: Okotoks and District Historical Society, 1983.

"Okotoks Erratic - 'Big Rock', Government of Alberta Website, https://www.alberta.ca/okotoks-erratic-big-rock.aspx.

Wynn, Graeme. "Timber Trade History," The Canadian Encyclopedia. July 26, 2013. https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/timber-trade-history,