Walking Tour

Life in Okotoks

Growing up in an Alberta town

Taylor Peacock, Elyse Abma

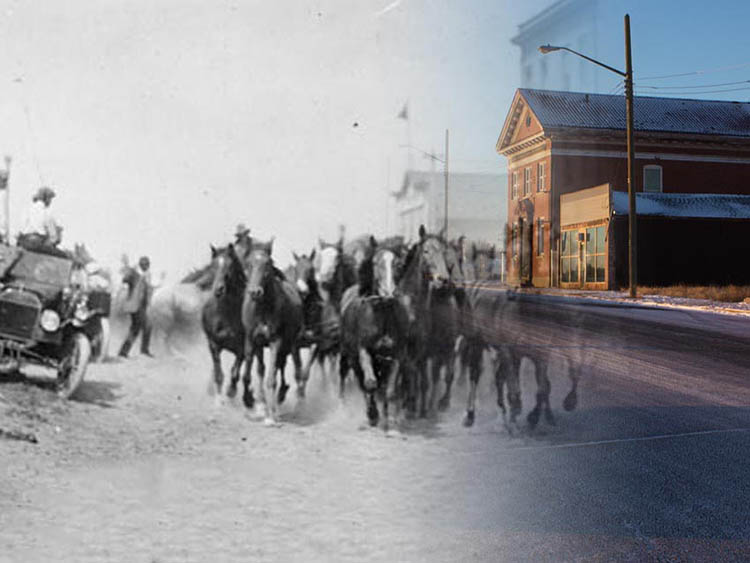

It has been almost 140 years since Europeans first settled in the area around Okotoks. Those first hardy pioneers started by building their own homes and businesses from the ground up. They endured challenges we can scarcely imagine living through today, and went without comforts that we can scarcely imagine living without. As more settlers came and the community coalesced into a town, the modern Okotoks we know today began to take shape.

What life was like for people in those days, roughly 1882 to the 1950s, is what this tour covers. We'll look at how they worshipped, how they learned, and how they thought the world ought to work. We'll also consider the challenges they faced, harsh winters, depression and recession, and two world wars, and see how the people of Okotoks rose to the occasion each time.

This tour is a short route through the residential streets of historic Okotoks, showcasing many of the beautiful heritage homes that have been preserved here. The tour starts in front of the Okotoks Museum and proceeds up Alberta Ave, and then turns onto McRae Street where you'll walk past the Old Towne Plaza. Next you'll take Clark Ave up to Elma Street, where many important heritage homes can be found on a pleasant tree-lined boulevard. Finally we'll come back down on to Elizabeth Street, and conclude near the Elks Hall.

This project is a partnership with the Okotoks & District Historical Society. We also would like to thank the Ridge at Okotoks for sponsoring our work trip.

1. Home on the Prairies

1930

We begin this tour at the house that once belonged to the Welch family. Mr. George Welch was manager of two grain elevators in town and also served as mayor of Okotoks. This home is an excellent surviving example of the type inhabited by the small professional middle class. It was originally located on the west side of town, where the Royal Bank is located today at the intersection of Northridge Drive and Elizabeth Street. It was later moved here to become the Okotoks Museum and Archives, a role it fulfills to this day.

The houses built in those early years were very similar to those in most Alberta communities. The vast majority were based on the designs popular in eastern Canada, the UK, and the USA. These designs were set down in pattern books that could be purchased at any lumber yard in Alberta for $5 to $10; the prospective homeowners could ask the builders to make alterations to suit their tastes.1

* * *

One further advantage of Okotoks’ favourable location was its easy access to vast supplies of timber. As a result, early settlers in the Okotoks area were able to make their dwellings from wood. This was not the case on much of the Canadian prairies where settlers in the 1870s and 1880s built their homes out of the closest material to hand: sod. These sod dwellings were known as ‘soddies’.

Once John Lineham, one of the earliest settlers in Okotoks, established a sawmill here in 1891, most early homes in Okotoks were built with wood from the sawmill. Lineham had a good supply of wood from timber leases in the foothills to the west, and used the Sheep River to float logs to his mill.

John Wilson came to Okotoks in July 1890 with his large family first living in a tent. He later got a job in Lineham’s sawmill and would bring home boards to build a new house. “Some boards were thick, some were thin, none planed, but the Wilsons were proud of their house for it was the first one built in the town with lumber from the local mill."

In 1886 there were already 20 houses in Okotoks though the railway wouldn't arrive for another five years.3

When the railway did arrive in 1891 -- with the train station opening in 1892 -- it brought an influx of settlers from Eastern Canada and the United Kingdom, who had very specific ideas about the kinds of homes they wanted to live in: ones that looked similar to those from where they came.

The railway allowed Okotoks residents to keep up to date on the latest home design trends sweeping Eastern Canada, the 'old country', and increasingly, the United States. People were "attracted by the models of domestic architecture portrayed in widely circulated magazines, newspapers, and house pattern books. These designs had the authority of being new, fashionable, and accepted by the dominant cultural group in society."4 As a result the homes in Okotoks came to look very much like those built most other places in Canada at the time.

2. Keeping the Faith

This photo shows the recently completed Lower School on the left, built in 1900, and St. Luke's Presbyterian Church at the right, built in 1897. Neither of these buildings survive, and the spot is now occupied by the provincial courthouse.

Around 1900, Okotoks could boast six different Christian congregations. In addition to the Presbyterians, there were Anglicans, Methodists, Baptists, Roman Catholics, and the Disciples of Christ. These six churches played a very important role in Okotokians' lives in the early 20th Century. They acted as social hubs where activities could be organized, like bridge clubs, literary groups, choirs, sports teams, and clubs like the Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire and Women's Christian Temperance Union.

* * *

By 1901, the Presbyterian congregation was by far the largest in Okotoks; over 40 per cent of the population. Historian Lewis Thomas explains how it represented "a cross-section not only of the town but of the surrounding countryside."

"It included the doctor, the editor of the newspaper and an Englishman, of genteel antecedents and some substance, who carried an increasing responsibility for the direction of the affairs of the town on the basis of sheer character and his conviction of the individual's responsibility for the welfare of his fellow men. Some of the merchants also attended, bank employees and teachers came and went, but in the church and its organizations many of the most faithful supporters were drawn from less prestigious occupations."2

The congregations often competed with each other for converts, and was the focus of intensive small town gossip. "There was some consternation," writes Thomas "when an Anglican soprano yielded to the allurements" of a better choir in a neighbouring church. "Or a well-off Presbyterian from the country appeared with suspicious frequency at St. Peter's [Anglican church]."3

Yet these differences were mostly cosmetic. For instance, in 1917 the Methodist and Presbyterian churches amalgamated into the United Church. The two churches in Okotoks were among the first in Canada to do so, demonstrating the cooperative spirit of this tightly knit community .4

3. Building a School System

1940s

A group of children pose for a class photo in front of the Lower School we saw on the last stop, now the site of the courthouse. They are dressed smartly for picture day, and the boy in the top centre proudly sports a hockey jersey. This was the second building to serve as the town's main school. The first was built in 1890, and was a simple one-room schoolhouse located about 1.5 km north of the village of Okotoks on the present D'Arcy subdivision lands.

* * *

By 1900, the village’s population had grown enough to warrant a new building, and the handsome brick Lower School was constructed on this spot.

Attendance standards were quite different back then, since many kids were taken out of school to help their parents on the farmstead during the summer. This meant education was a lot less comprehensive than it is today. As one scholar writes, "In the first decades of the province, few students progressed to secondary school. A student's education was considered adequate if he or she mastered the "3 Rs"—reading, 'riting and 'rithmetic, the equivalent of Grade 6–8. Attending high school was still a rarity."1

The town soon outgrew the Lower School, so the Upper School was built in 1912 atop the bluff just in front of you. It taught the upper grades, and the Lower School taught the lower grades. Ecole Okotoks Junior High is built on that spot today. The Okotoks Lower School was torn down in 1970.

4. Okotoks at War

1940s

This is a photo of Myrtle Robinson taken in front of the Okotoks Baptist Church during the Second World War as she was departing Okotoks to serve with the Women's Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRENS). It's one of a remarkable collection of photographs taken throughout the war by Laura Hole, the owner of the nearby shoe repair shop. She would take a photo of each man and woman from Okotoks who joined the armed forces and then display them in the drug store's window. She would afix coloured stars beside photos of servicemen if news arrived that they had been killed, wounded, or missing. The drug store window became a daily gathering spot for Okotoks residents fearing the addition of any stars.

* * *

As historian Lewis Thomas notes, "As in other areas with a preponderance of British-oriented young men of military age, enlistments and casualty rates were equally high."1 As the town emptied of young men, many of whom would never return, the women left behind yearned to do their bit to help the war effort, forming a Red Cross Society that raised funds and supplies for the troops.

Nevertheless, the war's cost in both lives and lost potential in Okotoks was extraordinary. Thomas continues, "Certainly the Okotoks of 1920 was a shadow of the optimistic and bustling town of the first decade... The price in social dislocation paid by the youthful communities of the west in the aftermath of 1914 has seldom been accurately calculated or even adequately described."2

When another even greater world war erupted just 21 years later, the people of Okotoks once again answered the call. Over 200 men enlisted in the army, navy, and air force, while 13 women like Myrtle Robinson enlisted in the Women’s Royal Naval Service (Wrens), the Canadian Women's Army Corps (CWACs), or the Women's Division of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Of that total, 15 Okotoks residents never returned.

At home, Okotokians once again pitched in to do their part. When the call went out for scrap metal to make munitions, the townspeople raised 19 train cars of it. They donated several tons of clothes to help those in other Allied nations devastated by the war. They founded a Blood Clinic and a Red Cross Society that made regular donations. Nine Victory Bond campaigns raised over $1.5 million from Okotokians, or over $2.2 billion in today's money.

On January 7, 1946 an event was held at the Willingdon Hotel to celebrate the return of the town's war veterans. The mayor delivered a message, saying "As you have been prepared to fight and risk your lives to establish Victory and a Lasting Peace, let me express the hope that you will be equally determined to put forward every effort to see that this Peace has not been won in vain."4

5. Feeding the Family

1911

Men stand around a horse and buggy in front of John Shield’s Fine Groceries and Warehouse. The grocery store opened in 1911, but didn't last long: in 1913 it burned down. It never reopened.

Like many small prairie towns in the pioneer era, Okotoks was divided into two distinctly gendered roles: the wage earners were primarily men, while the women were homemakers.

* * *

Another example is the sale of home-made butter in exchange for groceries in the early 1900s. "How well we remember the aroma of her freshly baked bread," writes Lillian Hogge. "Once or twice a week [mom] baked ten or twelve loaves. All of our butter was churned. She sold some butter to 'Pamments General Store', and in return got groceries, etc. Every summer 250-300 quarts of fruit were canned as well as many quarts of meat, jams, jelly and pickles. Much of the fruit that was canned was saskatoons, strawberries and raspberries that we picked in the fields, also lots of jam from chokecherries."3

Ads in old cookbooks provide another glimpse into women's lives and interests: alongside recipes for preparing cabbage, beans, beets, and dry goods, there were advertisements for fertilizers and farming equipment. Women on prairie farms near Okotoks would have been highly involved in the running of the farm.4

Grocery stores like John Shields’ store were vital in town, not only for the purchase of groceries, but where homemakers could sell their own produce or home-made goods. In Eastern Canada in the early 20th century, stores well stocked with fresh fruit, vegetables, and meats meant people had a diverse diet. In prairie towns like Okotoks, this was not the case. The harsh prairie environment meant farmers had to be exceptionally self-sufficient, growing the vast majority of fresh foods they required. Nor was it just farm families -- many town residents had huge gardens in their backyards, as well as a milk cow and chickens to supply their needs. Grocery stores focused on carrying basic food staples like flour and sugar, and mainstays such as 'sow bosom,' a type of salt fat pork that lasted over the long cold winters.5

6. Church and Community

This photo of St. Peter’s Anglican Church shows the gothic revival building that was built in 1905. By the 1920s, the two largest congregations in Okotoks belonged to the United Church and the Anglican Church. The United Church, the result of a 1917 vote by the Presbyterians and Methodists to amalgamate, was the largest.

The differences between the two congregations went beyond articles of faith. The Anglicans were predominantly English and more likely to be part of the local elite (including the apparently prestigious bridge club). Regular attendees at St. Peter's Anglican Church included the doctor, bank employees, merchants, teachers, and the newspaper editor, among others. The United Church was more popular with the working classes. The class distinctions were obvious to people at the time, and made the two congregations wary of each other.1 The divide between the two congregations was notable, but not significant, as Okotoks was still a small community.

* * *

Members of St. Peter's were also Masons, belonged to the Women's Auxiliary, or participated in other community activities. Activities and community events that were covered by the two religious groups rarely had any interfaith fighting, and as a community, everyone sought to get along. The community was largely homogenous, meaning that differences in worship were relatively minor.

As the 20th century progressed onwards, religious organizations came to play a lesser role in the day-to-day life in some communities; however, religion was still very much a part of the community in Okotoks. In the 1950s, R. M. Pow recalls about his years in Okotoks: "I was active in the business life of the town, and served a term as president of the Okotoks Chamber of Commerce and Agriculture. I was treasurer of the Canadian Red Cross Society, Okotoks branch, for ten years. Our family was active in St. Peter's Church. I served on the Vestry for a number of years; Kate was active in the Women's Auxiliary. I was also treasurer for some years and served as People's and Rector's Warden." 2

In 1992, St. Peter's parish outgrew the original 1905 church and moved to a new building. The former church is now an antique store.

7. Homeowning

1905

Home ownership in Okotoks ranged from grand brick residences to more modest wood-frame homes, like this one at 20 Elma Street East. One of the first owners of this home was Matilda (nee Fiske) Hamilton, widow of Robert Hamilton, and their five children. It is an example of the practical, homestead-style home commonly built at the turn of century; however, this home features significant gingerbread detailing which demonstrates the pride of ownership. Such homes provide a window into the small town Alberta culture over 100 years ago.

* * *

Often men would venture west alone to test prairie living, seek out employment and build a basic shack. Once satisfied with their new surroundings, they'd call for the rest of their family to join them. As these families became established and the town more prosperous, many early settlers began replacing their original dwellings with homes like these. This investment represents the confidence and optimism residents had in the future of the community.

Most wood homes built in Okotoks in those early days were typically one of three styles: a bungalow with low slanting roofs and a wide porch, a Victorian or Edwardian-style home with a tall gabled roof, or perhaps the post-Victorian foursquare where the home consisted of four rooms per floor. Homes like the one pictured above, with a little bit of Victorian flair on the outer balcony, were very common in Okotoks.

For the Okotoks gentlemen at the end of the Victorian era, homeownership was the ultimate goal, as it would grant them not only security, but privacy. An advertisement for homes in a Calgary newspaper in 1911 captured the spirit of the time: "try, try, economize, save, deprive yourself of luxuries and pleasures and rich garments in order to obtain this home, because the joy, comfort and feeling of independence you will realize later in life will repay you well for all your sacrifice."2

Nevertheless, hygiene was an ongoing issue. Combined with an absence of garbage disposal, running water, and electricity, the lifestyle of the people who lived in these homes was very different from present day. As one observer noted, "Every backyard and cesspool affords fruitful soil for the cultivation of disease germs. Wells are placed injudiciously, the water supply becomes tainted and typhoid appears on the scene"3

8. The Linehams

This photo is of Elma Lineham, one of John Lineham's two daughters. She is standing on the lawn of her uncle Will Lineham's brick home, with the north side of Elma Street in the background. Both John Lineham and Will Lineham owned houses on Elma Street as well as had homes on their ranches west of Okotoks.

* * *

In addition to lumber, Lineham and his brother were also purveyors of beef, keeping both Hereford and Shorthorn cattle on a 6,000-hectare ranch near Sheep Creek. Lineham was also a formative figure in the history of Alberta oil: he partnered with two businessmen to try drilling in what is now Waterton Lakes National Park, in one of the province's first oil projects. While the enterprise only lasted from 1901 to 1904, its pioneering nature made Lineham a historic name in the petroleum industry..1

John Lineham's community involvement extended to political leadership, where he served as mayor of Okotoks from 1909 to 1911. The Lineham families’ impact is acknowledged in Okotoks not only on Elma Street, where two Lineham residences are located, but also Elizabeth Street (named after his other daughter), Martin Avenue (named after his wife’s maiden name) and Lineham Avenue. John Lineham's name is further commemorated in southern Alberta with a creek, a chain of lakes and a mountain.2

9. Building Community

1965

Above we see the Legion Ladies Auxiliary marching on Elizabeth Street on Remembrance Day. In addition to the six church congregations, early Okotoks was held together by numerous social organizations and societies. These included fraternal organizations like the Freemasons, Orangemen, Elks, Knights of Pythias, and Oddfellows, as well as a number of women's organizations like the Eastern Star, Royal Purple, and Imperial Daughters of the Empire. Many of these clubs and organizations date back to the 1890s, and were an important part of the town's history.

* * *

Vera Martin recalls how the Orangemen's Hall provided a source of joy and community spirit during the otherwise harsh Depression. "During the depression years one of the highlights of the winter was going to dances at different neighbors' homes, Bird's barn, Cameron Coulee School, and the Orangemen's Hall in Okotoks. We always had good times at these dances and usually travelled by sleigh and horses."2

The Masons began in Okotoks in 1906, with the opening of the first lodge. Freemasonry is one of the oldest fraternal societies in Canada, introduced by British soldiers in the early 1800s.

In Okotoks, many of the significant members of the town were Masons, and deeply involved in community-building. The story of V.E. Hessell is one such story: "Mr. Hessell was described as being strict but honest in his dealings. He worked long hours, especially during the Depression. At that time, he set up a fund to provide meals for "drifters". He was Worshipful Master of the Corinthian Lodge in 1929, later served as a member of the Grand Lodge, and was a thirty-second degree Mason. He was twice Mayor of Okotoks, serving in 1922 and again in 1942-43."3

Women's organizations in Okotoks were notably absent in the early days of the town, but grew rapidly in the 1920s. In addition to the Legions Ladies Auxiliary, there was the Handicraft Guild, Rockettes, Farm Women, the Eastern Star, and the Women's Institute. These were places where women could share knowledge and socialize with other women, and help the community in the same way the men's fraternal organizations had done earlier.

Mary Bailey's recollections of the Rockettes highlights how important social organizations were for women in the Okotoks district: "The club had been organized to ease the isolation of farm women, chiefly those with young children, who came along to brighten our meetings. We welcomed new brides, and transient farm women; and enjoyed the children but missed them when they went off to school. Our circle of friends stretched and strengthened by the informal attitude of the members. We didn't mind dropping our dignity if the others laughed. The men folk jeered, and had pressing work on the back forty when we visited their farms."4

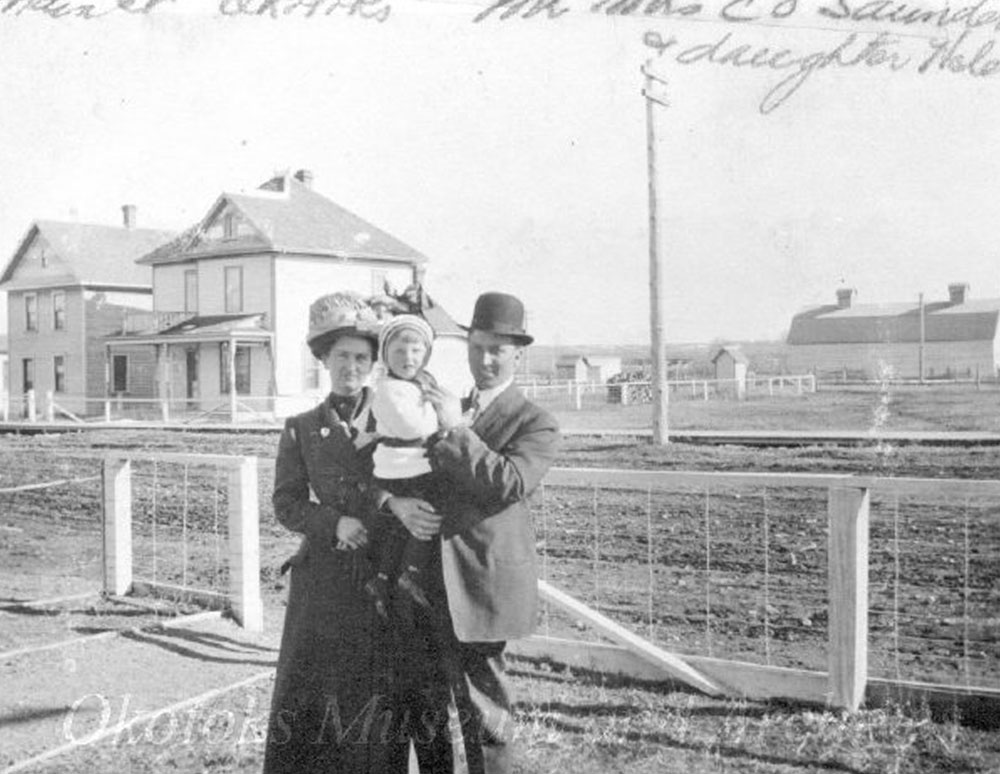

10. Cross-section of the World

Mr. and Mrs. Saunders and their daughter Helen pose in front of a few of the houses on what was then Main Street, now called Elizabeth Street. Families such as the Saunders -- with their lives, homes, jobs, organizations, struggles and triumphs -- have woven the rich tapestry that is the history of Okotoks.

* * *

Look a bit further though and the continuities from that time are everywhere. Organizations like the Masons, the Legion and the Elks are alive and well in Okotoks. The homes of John Lineham, Will Lineham and the Welch House are still standing.

As Dallas Banister Wright writes in the town's history book, Okotoks: A Century of Memories: "In retrospect, I see Okotoks as a cross section of the world at large. Found there were comedy, tragedy, wealth, poverty, jealousy, generosity, class distinction, a little vice, even a little scandal, but a great deal of neighbourliness and kindness -- each person made to feel a member of that large Okotoks family."2

Endnotes

1. Home on the Prairies

1. D. Wetherell & I. Kmet, Homes in Alberta: Buildings, Trends, and Design, 1870-1967, (Edmonton: University Alberta Press, 1991), 60.

2. Lewis G. Thomas, "Okotoks: From Trading Post to Suburb," Urban History Review. Vol 8: No 2, October 1979, 7.

3. Thomas, 9.

4. Wetherell & Kmet, 60.

2. Keeping the Faith

1. Okotoks and District Historical Society, A Century of Memories: Okotoks and District, 1883-1983 (Okotoks: Okotoks and District Historical Society, 1983), 32.

2. Thomas, 19.

3. Thomas, 20.

4. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 8.

3. Building a School System

1. The Alberta Teachers' Association, "The Founding of Alberta," online.

4. Okotoks at War

1. Thomas, 13.

2. Thomas, 12.

3. University of Alberta Libraries, "Souvenir presented to those men and women of Okotoks and district who served in the Armed Forces during World War II," (Peel's Prairie Provinces, 1946), online.

4. University of Alberta Libraries, online

5. Feeding the Family

1. C.R. Comacchio, The infinite bonds of family: Domesticity in Canada, 1850-1940 (Vol. 4), (University of Toronto Press, 1999), 34.

2. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 161.

3. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 296.

4. K. Kowalchuk, Community cookbooks in the prairies, Cuizine: The Journal of Canadian Food Cultures/Cuizine: revue des cultures culinaires au Canada, (2013), 4(1).

5. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 79

6. Church and Community

1. Thomas, 25.

2. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 193.

3. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 506

7. Homeowning

1. D. Wetherell & I. Kmet, 51.

2. D. Wetherell & I. Kmet, 47.

3. D. Wetherell & I. Kmet, 40.

8. The Linehams

1. Henry C. Klassen, “LINEHAM, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003), online.

2. Klassen, online

9. Building Community

1. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 695.

2. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 636.

3. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 286.

4. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 706.

10. Cross-section of the World

1. Town of Okotoks, "2018 Census," online.

2. Okotoks and District Historical Society, 2.

Bibliography

Alberta Teachers' Association, "The Founding of Alberta," online. https://www.teachers.ab.ca/News%20Room/ata%20magazine/Volume%2086/Number%202/Articles/Pages/The%20Founding%20of%20Alberta.aspx

Comacchio, C.R. The infinite bonds of family: Domesticity in Canada, 1850-1940 (Vol. 4). 1999. University of Toronto Press.

Kowalchuk, K. Community cookbooks in the prairies. Cuizine: The Journal of Canadian Food Cultures/Cuizine: revue des cultures culinaires au Canada, 4(1). 2013.

Klassen, Henry C. “LINEHAM, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003.

Okotoks and District Historical Society. A Century of Memories: Okotoks and District, 1883-1983. Okotoks: Okotoks and District Historical Society, 1983. https://cdm22007.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p22007coll8/id/1200377/rec/73

Thomas, Lewis G. "Okotoks: From Trading Post to Suburb," Urban History Review. Vol 8: No 2, October 1979, pp. 3-22. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/uhr/1979-v8-n2-uhr0895/1019375ar.pdf

Town of Okotoks, "2018 Census."

University of Alberta Libraries, "Souvenir presented to those men and women of Okotoks and district who served in the Armed Forces during World War II," Peel's Prairie Provinces, 1946. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/bibliography/6877/reader.html#17

Wetherell, D. & Kmet, I. Homes in Alberta: Buildings, Trends, and Design, 1870-1967. Edmonton: University Alberta Press, 1991.