Walking Tour

Nanaimo's Waterfront

The Key to Prosperity

By Andrew Farris

In this tour we will take a stroll along Nanaimo's harbour walkway, discovering how this stretch of waterfront has shaped Nanaimo's history and provided livelihoods for the people who called this place home. We will begin with learning about the Snuneymuxw, the First Nations people who have lived and fished here for thousands of years, and upon whose unceded territory Nanaimo is built.

Next w e will see how coal first drew Europeans here, and in the 1850s how they began mining and exporting the so-called 'black diamond' from wharves all around this harbour. We will also take a look at Nanaimo's two other main industries: fishing and lumber, and the city's close connection with the United States of America.

We will see how Nanaimoites have used this harbour as the main highway that connects them to the world and chart the rise and fall of a succession of ferry companies. Finally we'll see that the harbour isn't just a place of economic activity, but a place that people come to for recreation and fun. As the harbour has gradually shaken off its industrial roots it has evolved into the beautiful and appealing place we know today.

This project is possible with the generous support of the Nanaimo Hospitality Association and the Petroglyph Development Group of the Snuneymuxw First Nation. We would also like to thank the Nanaimo Archives and Nanaimo Museum for use of their historic photo collections and providing research assistance.

1. The Snuneymuxw People

1849

Nanaimo has changed an enormous amount in the last 150 years, and it may take a bit of imagination to see how these two photos line up. You can see Commercial Street on the left and the Bastion on the right. By the time that this photo had been taken in 1867, Nanaimo had been settled by Europeans for almost 20 years, but the people who came before—the Snuneymuxw—had already lived here for at least 4, 000 years.

Their huge dug-out canoes allowed them to range far and wide, while highly-developed hunting and fishing techniques meant they lived well off the Salish Sea's thriving sea-life. The arrival of European settler-colonists in the mid-19th Century caused incredible disruption to their traditional way of life, one that had found harmony with their own environment.

* * *

The Snuneymuxw moved between seasonal village sites across the region that included Departure Bay, the mouth of the Nanaimo River, and the False Narrows. They even canoed across the Salish Sea to the mouth of the Fraser River in time for the gigantic summer salmon runs. Archaeological excavations at their village site in Departure Bay showed just how varied their diet was: the remains were found of 30 species of birds, 14 mammals, and all sorts of fish and shellfish.2 Salmon were caught using ingeniously constructed weirs near the mouths of rivers, which acted like a small pen. Once the hapless salmon swam into the weirs they could be easily picked out by a skilled fishermen. Most fishing—for cod, herring, seals, and sea lions, among many others—was done from the Snuneymuxw's huge canoes.

2. Ki-et-sa-kun

1859

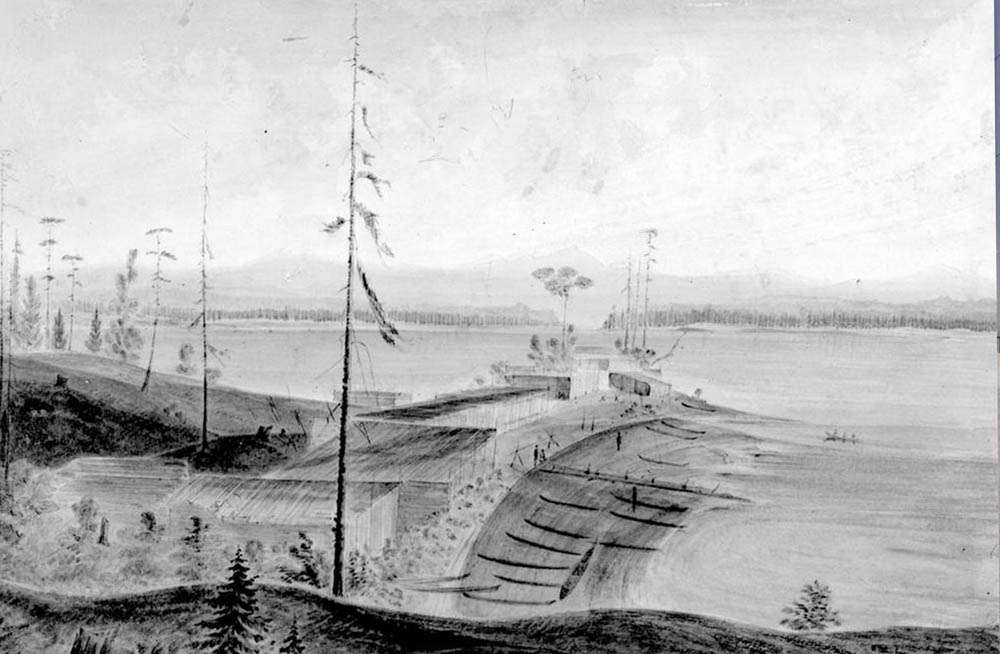

This very early sketch of the Hudson's Bay Company settlement in Nanaimo shows the Bastion, which survives today, and also the first mine shafts (at left) which do not. When Ki-et-sa-kun, a member of the Snuneymuxw, tipped off the Hudson's Bay Company about the rich veins of coal to be found here the white men arrived and set to work mining this valuable resource.

* * *

At this particular moment in the middle of the 19th Century an epochal shift was occurring. The Industrial Revolution was in full swing and technology was advancing in leaps and bounds. There were now factory machines that worked faster than any craftsman, trains that moved faster than a horse, steamships that could sail against the wind. Feats once unthinkable were now possible. All were made possible by coal. Coal had suddenly become one of the most precious commodities in the world - and Europeans had an insatiable thirst for it.

When the HBC's clerk Joseph McKay heard that Ki-et-sa-kun might know where more coal was, he was skeptical but he made the man an offer: bring some of it back in exchange for a bottle of rum and a free gun repair.

Months passed and the hunter's story was largely forgotten. Life continued in the sleepy fort. Then in the spring Ki-et-sa-kun returned with a canoe filled to the brim with high quality coal. The astonished clerk asked Ki-et-sa-kun to take him to the source of the black rock. In May 1850 they arrived at the spot you are standing on now.

They had found the best reserves of coal on North America's Pacific Coast.1 A statue of Ki-et-sa-kun, long since remembered by settlers as "Coal Tyee", stands in the Mark Bate Memorial Tree Plaza which you will see later on in this tour.

3. The Age of Coal

Nanaimo Community Archives 1997 031 A-P2

1900

This photo looking up Front Street shows some of the first buildings constructed by the British settlers. The Bastion, which was built in 1853, was still in its original spot when this photo was taken (it has since been moved to its present location across the street), and behind it are a number of the cramped cottages that housed the first miners to arrive from Britain. It was at this spot that the first miners landed, intent on improving upon their failed mining venture at Fort Rupert far to the north.

* * *

At that time only a few hundred Europeans lived on the island (almost none lived on the mainland). Most were fur traders working for the Hudson's Bay Company who knew little about mining coal.1 Yet the Company's management saw the strategic value of these resources and sought to expand into this lucrative new industry. In 1846 they hired four miners from the coalfields of Scotland to start mining at remote Fort Rupert, located on the northeastern tip of Vancouver Island.

At Fort Rupert the ridiculously small number of miners were aided by the local First Nations people, who mined coal in exchange for blankets. The conditions were miserable and the Scotsmen lacked proper mining equipment, while the HBC managers had them digging in all the wrong places.

By 1852 the Scottish miners - John Muir, his sons Robert and Archibald, and John MacGregor - were close to mutiny. When word reached Fort Rupert of the vastly superior coalfields around Nanaimo, the HBC saw an opportunity for a fresh start and transferred them there. They arrived that August, the first white settlers in Nanaimo.2 r

4. The Settlers Arrive

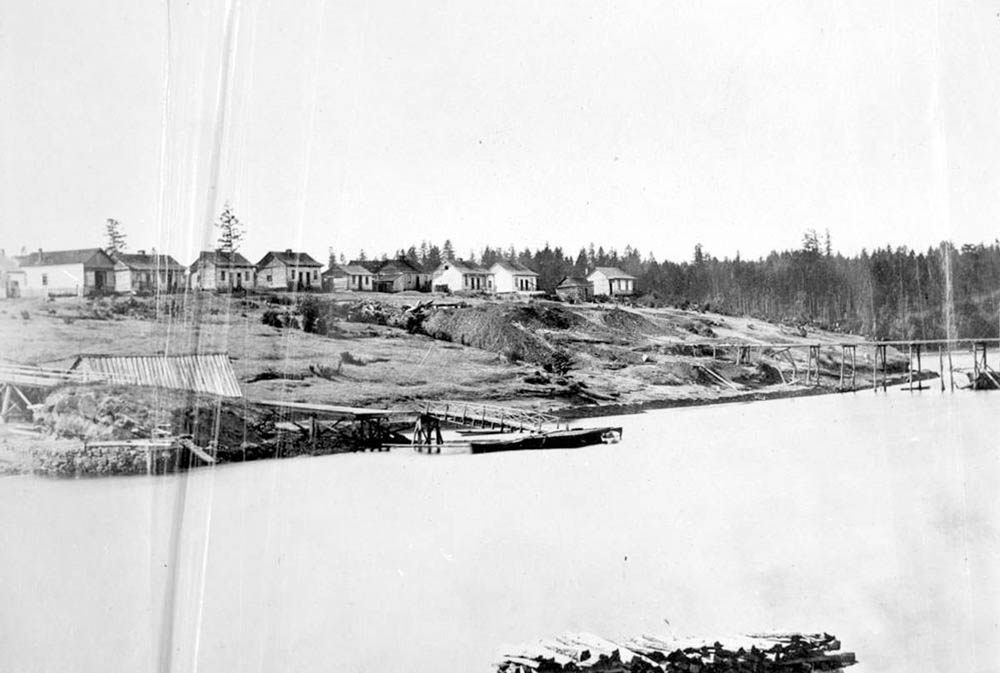

1860s

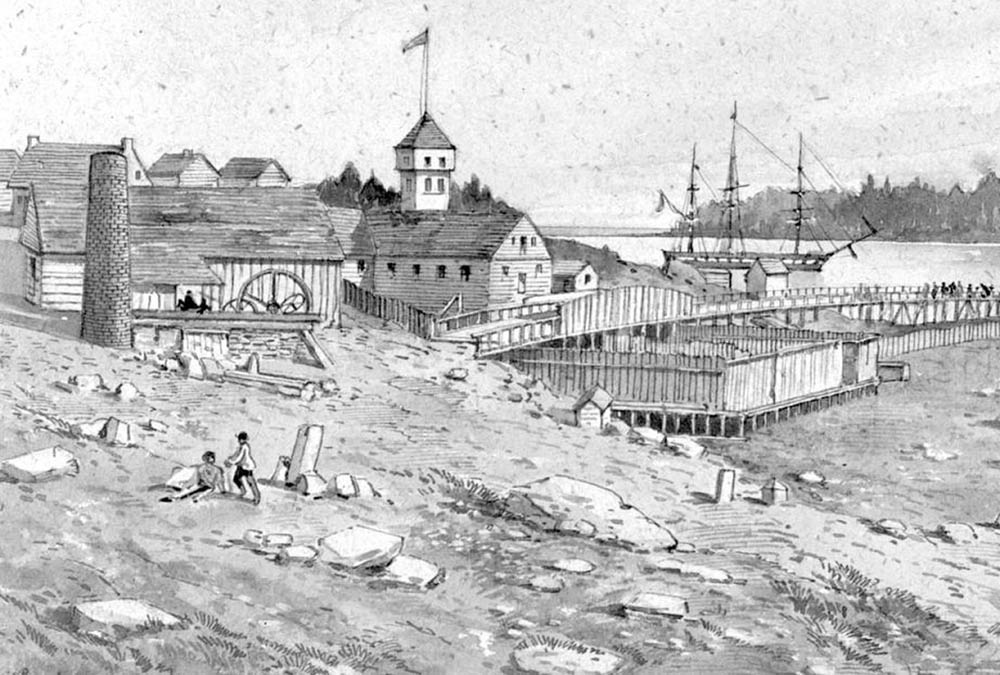

A view across Commercial Inlet in the 1860s. We can see that a small community centred on the Bastion has taken shape. See how the waters of Commercial Inlet then extended further inland past where the Port Theatre stands today. This inlet once extended all the way up Terminal Ave. where the highway runs today, making downtown Nanaimo into a narrow peninsula of land. Most of the inlet was filled in during the 20th Century, largely from the mine tailings from the network of shafts that extended under downtown.

* * *

The Princess Royal set sail from the United Kingdom on June 3, 1854 with a complement of 23 men, 23 women, and many children. It was a gruelling, cramped, storm-tossed voyage around Cape Horn and up the Pacific Coast. When they at last arrived in British Columbia six months later, two adults and six children had died and three new babies had been born. After switching to the paddlewheeler SS Beaver in Fort Victoria, they set out on the final leg of their journey to Nanaimo. When the weary settlers dropped anchor in this harbour they saw that the entire settlement had turned out to greet them: 150 settlers (almost all male HBC employees) and a number of Snuneymuxw.2 The settlers rowed to shore and first set foot on a big rock, we know it today as Pioneer Rock. It's just beneath where the Bastion now stands. A commemorative cairn has been placed there to mark the occasion. It is somewhat obscured by the car park that's there now.

McKay and his Hudson's Bay Company men who had arrived in Nanaimo two years before in 1852, had been busily building up a settlement. McKay arrived first in mid-August and made arrangements with the Snuneymuxw's Chief Wun-wun-shun for the HBC to take possession of the coal beds and pay the Snuneymuxw to mine for them. Then the Scottish miners from Fort Rupert arrived and began working with the Snuneymuxw, supervising them in mining coal and constructing huts to live in. Moving remarkably quickly, enough had been mined with in two weeks to fill the ship Cadboro with 480 barrels of coal. The ship Recovery sailed for Victoria on September 30 with a further 1,391 barrels of coal.3

That coal came from the first mine located across the inlet from where you are standing now, on the slope to the left of the Coast Bastion Hotel. The mine shafts were rudimentary and became increasingly dangerous as the miners delved deeper into the earth. The coal was packed into baskets and Snuneymuxw women took it in their canoes and paddled out to ships anchored in the harbour to load it.. Initially the miners were Snuneymuxw men overseen by the experienced Scottish miners, but as more settlers arrived and more mines opened the Snuneymuxw were relied upon less and less, much to their frustration.

The HBC had been losing interest in fur trading and mining and were determined to shift their energies into establishing a chain of department stores (a wise business choice if the company's continued success is anything to go by). In 1861 they consolidated all their Nanaimo mining operations into the Vancouver Coal Company (VCC) and sold the company to a group of London investors. This was a major change: Nanaimo had grown up as a company town and the HBC had acted as a sort of quasi-independent government. Most of Nanaimo's inhabitants were there on indentured work contracts for the Company. The Company supplied the settlers through its store, oversaw the building of infrastructure like roads and bridges, and supervised mining operations. Now all these responsibilities fell to the VCC.4

5. The Bastion

1872

This is the paddlewheeler SS Maude moored at the government wharf in downtown Nanaimo. The photo was taken right when the Maude began ferry service between Vancouver, Nanaimo and Victoria. It was the first ferry in the Salish Sea.1 In these early years the small group of white settlers were isolated from the outside world and feared attack from the First Nations peoples upon whose land they had settled, and who still outnumbered them. As a precaution the settlers built the defensive Bastion in 1853. In the end their fears proved to be unfounded.

* * *

Fortunately for the settlers the Bastion proved unnecessary. The Europeans suffered from a chronic shortage of labour and relied on the Snuneymuxw to do most of the coal mining and logging in exchange for trade goods. At first it was a mutually beneficial relationship but the Snuneymuxw soon found the Europeans were hiring First Nation peoples from other bands to work for them and they justifiably feared losing out. It was a dispute over this monopoly that precipitated one of the most dramatic events in Nanaimo's history.

As historian Jan Peterson describes it in her book Black Diamond City, one day in late 1854 members of the Snuneymuxw discovered a party of Ligwilda'xw logging for the new settlers. These were a First Nations people from what we now call Quadra Island and the area around Campbell River. When confronted, the Ligwilda'xw refused to stop logging, and a brawl ensued that left three of them dead and the rest fleeing.

A few days later the Snuneymuxw and the settlers awoke to the terrifying sight of 100 war canoes sailing into the harbour you're looking out at now. The canoes were filled with heavily armed Ligwilda'xw men in war paint. Captain Stuart, the HBC's chief factor, ordered all the women and children into the Bastion and frantically prepared the town for attack. Then the shocked settlers watched as 40 Snuneymuxw war canoes went out to meet the invaders in the middle of Nanaimo's harbour. They were under the command of Chief Wun-wun-shun. Wun-wun-shun was widely regarded by both Europeans and First Nations people up and down the coast as a wise and just leader. Seeing that his own people were hopelessly outnumbered he went to parlay with the Ligwilda'xw Chief.

Peterson picks up the story:

"Tension ran high as the chief of the Kelwiltoks rose in his canoe demanding reparation. Snuneymuxw Chief Wun-wun-shun acknowledged the justness of the demand. This put the angry chief at a disadvantage. He thundered, 'Three Ligwilda'xws have died. Three Snuneymuxw must die! And there must be reparations as well.'

"Chief Wun-wun-shun agreed. A silence fell over the group. Who would the three Snuneymuxw be? No one offered to sacrifice himself. If he chose someone and they refused, the Ligwilda'xws would attack. This was no time for discussion.

"The wise old Chief knew he had to do something to avert a massacre. He rose slowly in his canoe and with dignity addressed the hostile visitors. He told them who he was and they listened with respect. Was he not a great chief? Was he not a warrior famous along the coast? After telling them of his prowess he ended by saying 'Surely I, the Great Wun-wun-shun, am worth three common men! If you agree, kill me and let our people be friends.'

"There was whispered conversation between the Ligwilda'xws and then the commotion ended. The northern chief stood and accepted the offer. The Snuneymuxw sat in stunned silence as Chief Wun-wun-shun stood up in his canoe and faced his executioners. Twice they fired to wound. He made no move as musket balls tore at his flesh. Then a third shot was fired. The ball struck him between the eyes. Chief Wun-wun-shun had brought peace to Nanaimo."3

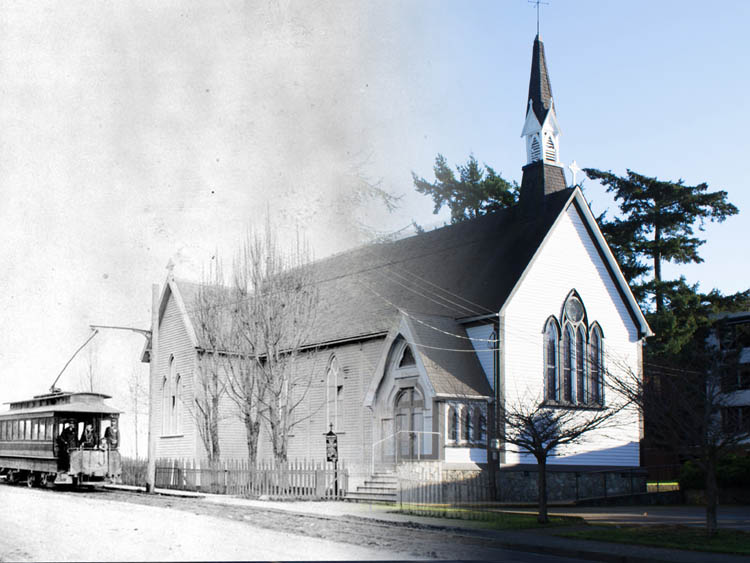

6. Settler Life

1860s

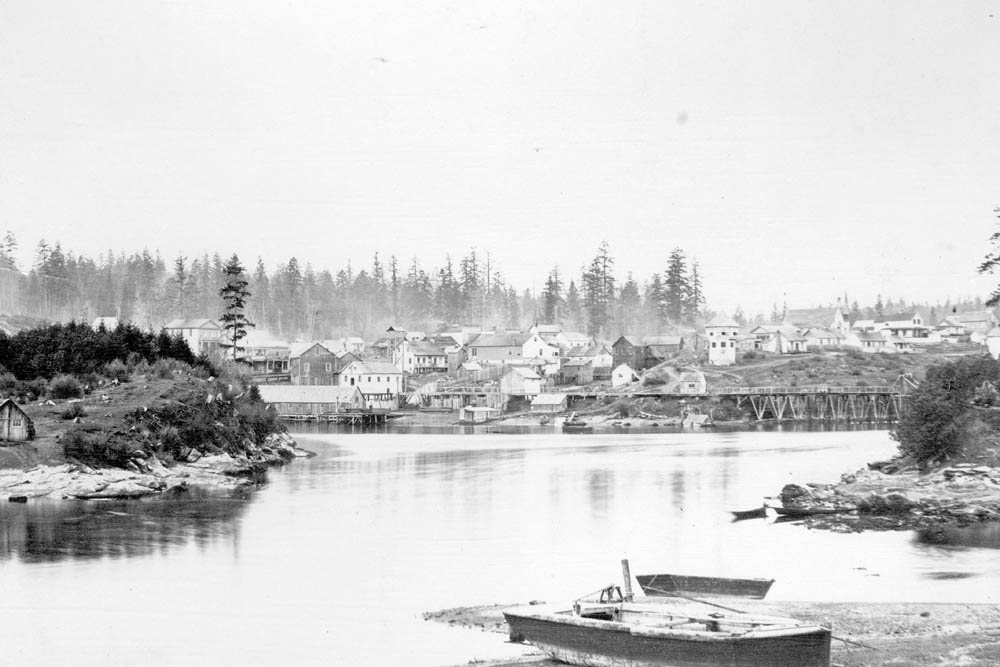

The homes of miners line Nanaimo's waterfront. These homes offered only the most rudimentary shelter for the slow but steady flow of immigrants, and there can be no doubt that life in Nanaimo in these early days was filled with immense challenges. Written accounts from this time frequently mention one big consolation prize: Nanaimo was then, as it remains today, a place of wondrous natural beauty.

* * *

Many of those early settlers couldn't help but be struck by Nanaimo's breathtaking natural setting and the kindness and hospitality of its inhabitants. Years later, Mark Bate would write a poem about his fond memories of the first time he saw the town.

"Since first Nanaimo shores I sighted With what a fierce and fearless thread I on the rugged beach alighted A landing place to step upon Nor a wharf at which to tie The Beaver anchored in the stream Off Cameron Isle nearby Kind hearts and hands Even then were here To greet a stranger who had come to stay Of the whole souled folk he then did meet"2

7. America's Special Relationship

1916

This is the SS Quadra sinking just off Protection Island after colliding with the SS Charmer. The Quadra had a long and eventful career that touched on different parts of Nanaimo's maritime experience, including Nanaimo's special relationship with the United States. The ship's career didn't end with this unfortunate sinking—it was refloated and repaired shortly after—and it ended life as a rum runner to America during Prohibition. Seized by the US Coast Guard in 1924, the old, water-logged ship sank at her moorings in San Francisco.

* * *

Migration went the other way too: glamorous and dynamic San Francisco was too tempting to resist for many of those bound for Nanaimo. In 1862 the HBC thought there were 100 men for every woman in Nanaimo and to rectify this helped set up the BC Emigration Society in England to encourage female settlers to come to the colony. The first of these "bride ships" was en route to Nanaimo when it put in at San Francisco. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the brides were somehow induced to stay in the American city and the ship never made it to remote Nanaimo (though fortunately for Nanaimo's lonely men, two later bride ships did in fact make it all the way).1

In the following years it would be the trade in coal and sandstone that bound Nanaimo's fortunes to America. While Nanaimo's coal reserves were the best on the Pacific Coast, British Columbia's tiny white population and relative isolation meant the most obvious markets for this coal were the booming American cities on the Pacific Coast.

Trade with the USA began almost right away when coal mining operations began in Nanaimo. Cargo ships like the Quadra would take on barrels of coal at the wharves that lined Commercial Inlet and depart for markets in Seattle and San Francisco. Coal didn't just fuel steamships, but was also used in indoor ovens for heating and cooking. Nanaimo coal was prized because of how little smoke it produced.

Robert Dunsmuir, that titan of provincial history, had been working as a notably diligent coal miner in Nanaimo and saw the potential to greatly expand this American trade. In 1869 he set up a new company to exploit the rich seams of coal around Departure Bay. He partnered with American business interests to run a steady stream of ships from his pitheads in Wellington (now northern Nanaimo) to San Francisco. The venture proved so successful that other San Francisco businessmen imitated it, setting up the nearby East Wellington Colliery that competed with Dunsmuir for lucrative American market share.

Coal wasn't the only minable wealth that blessed Nanaimo: It was soon discovered that Saysutshun, or Newcastle Island as the settlers called it, possessed exceptionally high quality sandstone. Indeed it was thought to be better than any sandstone deposits in America. A new quarry on that island was soon at work exporting blocks of the stuff. The old San Francisco Mint was built with Newcastle sandstone. Completed in the 1870s, it survives to this day, which cannot be said of many other buildings that stood before the catastrophic 1906 earthquake.

These economic ties bred closer political ties too. From their vantage point in the sleepy British colony, some Nanaimoites looked enviously at the energetic and expanding American states. The colonial government in Victoria took barely any interest in the affairs of Nanaimo, and many began to view Victoria as a "cruel step-mother".2 It was largely left up to the Vancouver Coal Company to do most of the things we expect of government today, like building infrastructure and providing jobs. Multiple attempts by Nanaimo to get funding for a road between Victoria and Nanaimo were frustratingly rebuffed.

When British Columbia debated joining the Canadian Confederation, the Nanaimo Tribune might have captured prevailing local attitudes when it instead advocated for joining the United States. Using a fitting nautical reference, an editorial described the Canadian project as a "fast sinking ship," while the United States was a "gallant new craft, good and strong, close alongside, inviting us to safety and success." The Nanaimoites were brushed aside however and reluctantly entered Canada in 1871.3

8. The End of Coal

1901

The SS Titania pulls away from the coal wharf that exported the coal from Nanaimo's Esplanade No. 1 Mine, located just south of here within the modern logging terminal. Its mine shafts extended underwater all the way out to Protection Island to the left of this photo's frame. The No. 1 Mine was the region's largest and produced the most coal of any underground mine. But like most of the mines around Nanaimo, it would eventually close as Nanaimo's economy struggled in the Great Depression.

* * *

The work of mining was back-breaking and terrifyingly dangerous. The biggest threat were the pockets of methane embedded in the coal seams. An unsuspecting miner could break into a pocket and then have the shaft fill with colourless, odorless, highly explosive methane, (basically natural gas). It could asphyxiate the miners or, with the tiniest spark, cause a gigantic explosion and collapse the shaft. Initially only the most rudimentary precautions were taken to ensure the safety of the miners, which is evidenced by the 31 miners who were killed by explosions in 1884 alone.2

Yet these frequent minor accidents paled in comparison to the catastrophe of May 3, 1887 that occurred in the maze of shafts that still lie under the waters in front of you. On that day 155 men went down for their shift in the No. 1 Esplanade mine and later in the day there was a tremendous explosion heard at the shaft. The men on the surface fought desperately to get down into the shaft but were only able to find 7 survivors before finding the shafts blocked.

Day and night the rescuers worked to reach the trapped men. Some were reached, but too late: they had long run out of air. Tragically, it was found they had scratched farewell messages to their loved ones in the dust on their shovels. 148 men are thought to have died, the worst mining disaster in the province's history. In the aftermath tensions ran high as white miners scapegoated the Chinese miners, blaming them for being unable to read the English warning signs.

A memorial plaque marking the disaster was erected on Milton Street and when viewed by our modern eyes, unintentionally adds another dimension of horror to the tragedy. It records the names of 97 white miners. The 53 Chinese miners are identified only by their work numbers as their names remain unknown, lost to history. At the time mining companies didn't even bother to record the names of their Chinese employees. It is shocking to come across such a blatant reminder of the casual and cruel racism of those times.3

Despite the disaster this mine reopened shortly after. New technologies and more workers caused mine output to increase rapidly. In 1923, the peak year, 1.3 million tonnes of coal were extracted in Nanaimo by 3,400 miners. The industry's collapse came rapidly after the peak, when demand for coal fell off a cliff in the Great Depression. In 1930, at the Depression's start, the number of miners quickly shrank to 2,158, the beginning of an inescapable trend. The Esplanade No. 1 mine closed forever in 1938.4

Some of the other mines clung on a little longer, but everyone could see the writing on the wall: the invention of new, vastly more efficient surface mining techniques opened up huge new coal reserves in British Columbia's interior. About six of those surface mines still operate today and the several hundred people who work at them produce around 25 million tonnes of coal a year. When you compare that to Nanaimo's peak year of 3,400 miners producing 1.3 million tonnes, it becomes clear there was no way underground mining could compete.5

By 1960 there were only 14 coal miners working in Nanaimo: the coal era had come to a close. But as we will see, new avenues were opening up for Nanaimo to travel down in the search for prosperity.

9. The Fisheries

1890s

In addition to the coal freighter you can see sailing into harbour, the fishing boats that once docked at these rather beaten-up looking docks were another key aspect of Nanaimo's early economy. Fishing took off in the early 1900s but was dealt a major blow as Japanese-Canadian fishermen, who played a central role in the industry, were interned in the Second World War and their boats sold off. At the same time a brief stint of whaling did lasting ecological damage.

* * *

The herring fishery was dominated by Japanese-Canadians, the Nikkei, who set up salteries and canneries that lined the Newcastle Passage all the way up to Departure Bay. The largest of these, Ikeda and Co. at Departure Bay, employed 500 people and exported direct to China and Taiwan.2

A magazine article in 1908 described the amazing bounty the herring fishermen saw:

Nanaimo Harbour is yearly the scene of the most remarkable herring run on the Pacific Coast. For several months in the year the harbour fairly teems with herring, at times the run being so remarkable that the herring pile up on the beach several feet deep. The fish are so thick on occasions that they actually smother themselves and float to the surface.3

One does not see sights like this today, a sad reminder of the extent of overfishing.

There was so much sea life to be had that the Pacific Whaling Company (PWC) established a whaling station at Page's Lagoon (now Piper's Lagoon), to the north of Departure Bay. It hunted the humpback whales that wintered in the Salish Sea. In 1908, just one of the station's two seasons of operation, over 500 humpbacks were hunted and boiled down for whale oil. Diminishing returns caused the PWC to shut down the station at the end of that season, though they kept running other ones.

By 1913 the other whaling stations had succeeded in systematically eradicating the humpback populations in the Salish Sea, catching 5,619 in an eight year period. Then the company immediately went bankrupt. The humpbacks have never returned to winter in these waters.4

As for the fisheries, they continued to grow through the First World War and in the following decades until the fateful year of 1942. That year, following Japan's attacks on the Allies, British Columbia's white population was swept by a paranoid hysteria about the threat of Japanese spies and saboteurs, and demanded the government imprison all Japanese-Canadians. The Canadian Government knew that the military threat posed by these people was remote. Many of them had lived in British Columbia longer than most of the white population, and strived through every means at their disposal to demonstrate their loyalty to Canada. In reality this hysteria was motivated more or less entirely by widespread racism towards the Japanese and a desire to remove them as economic competitors.

Nevertheless, the federal government obliged the demands and detained all Canadians of Japanese descent and exiled them to internment camps in the British Columbia's remote interior for the duration of the Second World War. Their businesses, fishing boats, homes, and property were all auctioned off at bargain basement prices. If you needed any confirmation that this was about racism and not military necessity, it wasn't until 1949 that the Japanese Canadians were allowed to move back to the Pacific Coast, 4 years after the war ended. By then, with their livelihoods stolen and little to return to, relatively few Japanese-Canadians ever returned to Nanaimo.

At the time the government saw fishing as a new industry that miners could move into as coal exports entered terminal decline. They were helped by the huge stocks of fishing boats and equipment seized from the Japanese. In an effort to boost this industry in 1943 the government bought some of the docks in front of you for fishing boats and dredged Commercial Inlet deeper into the shape you see today, allowing bigger ships to moor here.5 Since then the fishing industry has declined in relative size, but unlike coal mining it still plays an important role in Nanaimo's economy. Fishing boats can still be seen tied up at the floats you see around you.

10. The Rise of Forestry

1870s

Here we see cargo ships in Nanaimo harbour, some taking on coal at Cameron Island to the right while others are moored just offshore. In a sign of the changing economy, in the 1930s the Cameron Island wharf was converted to move lumber instead of coal. Surrounded by dense stands of old growth trees and having easy access to forested slopes up and down the coast, Nanaimo's harbour became BC's main forestry hub.

* * *

In 1875 the industry began to expand and a logging camp was set up at the mouth of the Nanaimo River. By the turn of the 20th Century there were three sawmills operating in the Nanaimo region employing 320 men.1 Half were white, and the other half were either First Nations or Chinese. The industry continued to pick up steam in the 1890s after the arrival of the E&N Railway opened up whole new areas away from the coast where the lumberjacks could practice their trade.

For many of these men logging was summer-time seasonal work; in the winters they went down into the mines. Logging was backbreaking, dangerous work. Once the trees were cut teams of oxen or horses would haul the logs down to the water where they could be floated to a mill.

In 1935, seeing the collapse in coal mining, the government sought to stimulate forestry by building the National Assembly Wharf, a major lumber export terminal, replacing the coal wharf in the photo. The stimulus program was successful and by 1948 there were 15 logging companies with offices in Nanaimo in addition to other sawmills in the region. With the post-war building boom in full swing the harbour hummed with activity. In 1950 alone 88 freighters and 199 tugs took on lumber at the wharf.2

Nanaimo had found a new industry to pin its economic hopes on after the decline of coal. Many of the forestry companies started here rose to become industry leaders, developing innovative new technologies and techniques. One example was the Mayo Lumber Company, founded by Indo-Canadian Mayo Singh, which built a state-of-the-art sawmill just south of the Snuneymuxw reserve in 1958. Before long the company's signature 'Diamond M' logo became a byword for quality across North America.3

Another entrepreneur, Sam Madill, started in Nanaimo shoeing horses at Wilkinson's Blacksmith before moving into forestry equipment and starting S. Madill Limited. From his shop once located in today's Maffeo Sutton Park, he invented a range of forestry equipment, such as "dozer boats" that shepherded logs, and portable spars for logging trucks. These innovations are used by logging companies around the world today. S. Madill continues in Nanaimo, churning out new equipment from their shop on the Island Highway.4

Another innovator was Harmac, a company that opened a waste wood pulp mill in 1950, making pulp for cardboard and paper bags. Harmac became very popular in Nanaimo for their high pay ($1 an hour in 1950) and bonus Christmas turkey for each employee. Less fondly remembered is the pungent smell that drifted from their plant south of Duke Point over to Nanaimo.5

While the industry employed thousands at its peak, the depletion of the forests and the automation of jobs mean that fewer Nanaimoites work in this industry today. Nevertheless it still plays a central role in the city's economy and cultural identity.

11. The Ferry Struggle

Vancouver Archives CVA 586-3160

Oct. 6, 1944

Seen here is the CPR's state-of-the-art ferry terminal on Cameron Island shortly after its construction. One of the two new ferries, either the Princess Marguerite or Princess Patricia, is taking on passengers. When this photo was taken these ferries were the latest entries in a long-running competition for control of the ferry service in Nanaimo. Ferry services linking the city to Vancouver and Victoria have been one of the defining aspects of life in the city for over 130 years.

* * *

It wasn't long for the first competitor to enter the scene: in 1884 a consortium of Vancouver Island businessmen created the People's Steam Navigation Company (PSNC). Fortunately for Dunsmuir, these were not particularly prudent businessmen: their first ferry, the SS Amelia, was an old paddlewheeler from San Francisco that cost a fortune just to get to Nanaimo. Once it arrived the two companies competed viciously for control of the Victoria-Nanaimo route, sending passenger fares into a death spiral as each company tried to bankrupt the other.

Robert Dunsmuir knew that his most ambitious venture, the E&N railway connecting Victoria and Nanaimo, would soon be complete and would render the Vancouver-Victoria route largely pointless. Cleverly, he offered to withdraw his ferries from the route in return for a share of the PSNC's profits. The consortium jumped at the opportunity and agreed to the deal. It didn't take long for them to realize they had been duped. The E&N railway was completed in 1889, causing the ferry passenger numbers to collapse overnight The PSNC went bankrupt within months. To add insult to injury Dunsmuir's CPN bought the SS Amelia at the bankruptcy auction.1

Now attention shifted to the booming metropolis of Vancouver, which was rapidly becoming the economic powerhouse of the province. In 1891 the Vancouver-based Union Steamship Company put the SS Cutch on the Vancouver-Nanaimo route. The modern and luxurious Cutch completed the passage in three hours, stealing passengers from the slower Robert Dunsmuir.

Dunsmuir and the CPN was furious. The Union Steamship Company already had many ships profitably running other routes and could not be chased out of Nanaimo in a price war like the People's Steam Navigation Company. Instead the CPN started an arms race in ferry quality by commissioning a faster and more luxurious ferry, the City of Nanaimo. Soon after they added another ferry to the route, the Joan. Nanaimoites were horrified: Robert Dunsmuir and his son James were shrewd businessmen who already controlled the E&N Railway. If they were able to get the Union Steamship Company to drop out they would hold an uncontested monopoly over Nanaimo's sea and rail links to the outside world.

The bitterness of the rivalry between the two ferry companies was illustrated in 1892, when the City of Nanaimo and Cutch were both departing Nanaimo's ferry wharf in front of where you now stand. The City of Nanaimo departed first, literally racing to be the first to Vancouver. The crew of the Cutch worked frantically to cast off and give chase. The CPN's second ferry though, the Joan, was also just leaving for Victoria and departed slowly, blocking the Cutch's way. The Cutch's captain was enraged and ordered his vessel full steam ahead. The two ships collided and the Joan was badly damaged. Unconcerned, the Cutch powered on in pursuit of the City of Nanaimo, leaving the Joan drifting in Nanaimo harbour with black smoke belching from her funnels. It must have been an exciting day to be a ferry passenger. The courts found the captain of the Cutch at fault and the Union Steamship Company was ordered to pay a huge settlement which practically bankrupted the company.2 A few years later they dropped out of the competition. Dunsmuir's cut-throat business tactics had won the day.

12. The Princess Ships

Vancouver Archives CVA 260-1311

1939

The Princess Victoria moored at the Canadian Pacific dock, the successor company to Dunsmuir's Canadian Pacific Navigation. From the 1900s these liners dominated the ferry service in and out of Nanaimo, but changing conditions and a new competitor in the 1950s caused their demise. This finally resulted in the creation of BC Ferries, ending once and for all the Wild West style competition between ferry companies.

* * *

It was during the economic boom after World War II that Canadian Pacific (CP) got rid of the old terminal you see in this picture and built the Cameron Island terminal seen in the previous photo. But their attempts to stay on top by cranking up the level of luxury and comfort on their pocket liners while continuing to build ships with slow side-loading systems for cars was a huge error: now lots more people were travelling with their cars and they wanted to get where they were going fast.

Front-loading or Roll on/Roll off ferries were much faster at loading and unloading cars, and they could also fit a lot more of them. An American competitor spied an opportunity and in 1953 Black Ball Ferries opened its own terminal at Departure Bay (CP refused to share the Cameron Island terminal with them). Their ferries were front-loading, the style of all ferries in BC today, and they promised a sailing every two hours. Canadian Pacific had met its match and immediately struggled, cutting routes and costs.

The competition between the two companies also drove down the wages of the ferry workers. In 1958 the CP workers went on strike. Employees of Black Ball went on strike in sympathy. Suddenly Vancouver Island found itself effectively cut off from the mainland, to the dismay and outrage of British Columbians who had come to take the ferries for granted.

Larger-than-life premier W.A.C. Bennett stepped in, decisively announcing his government would start its own ferry company with ships on the same design as the Black Ball ships. In 1959 Canadian Pacific cut most of their sailings. At the same time the owners of Black Ball decided to cut their losses and sold all their assets to Bennett's new crown corporation in 1960.2 Thus BC Ferries was born and the age of fierce ferry competition in British Columbia came to an end... Though there are some who might wish it would return.

13. Towards the Future

Nanaimo Community Archives 1997 026 A-P22

1915

Some small boats set off on a race by today's Maffeo Sutton Park, with Protection Island and "The Gap" separating it from Saysutshun in the background. Nanaimo's waterfront hasn't just been this port city's economic heart, but its playground and focus of social and community activity. The draw to the waterfront has increased dramatically in recent years as the bustling wharves and mills have given way to parks, restaurants and a continuous seawall.

* * *

After the Second World War the popularity of cars meant it was possible to move many industries to the outskirts of town and people could commute to them. So the industrial buildings were gradually torn down. As they left the city began acquiring the leftover land in the 1940s, slowly expanding the publicly owned portion over the following decades as each plot of land became available. By the late 1970s the park was beginning to take shape, and in 1984 the Swy-a-lana Lagoon, beside where you are standing, was built. By the 1990s the Harbour Front Walkway was built and finally in 2006 the ageing Civic Arena was demolished.1

Through the concerted efforts of generations of Nanaimoites, the toxic pollution from decades of heavy industry has been painstakingly cleaned up and this park has become the tranquil and beautiful place you see today. Work is not yet done and there are new rounds of improvements on the way.

This transformation has drawn community activities to the waterfront. The most famous is the rather grandiosely named "Great" International World Championship Bathtub Race held every July. The first race was held in 1967 to mark Canada's Centennial and involved a race in "bathtubs"--tiny boats like the ones pictured—across the choppy Salish Sea all the way to Vancouver. Since then it has become an annual event drawing thousands of locals and visitors to this park, though the course is now a circuit around the islands off Nanaimo that ends in Departure Bay.2

There's other events too, like the Silly Boat Regatta and Dragon Boat Festival that showcase ways people here take advantage of Nanaimo's waterfront setting.

Endnotes

1. The Snuneymuxw People

1. Jan Peterson, Black Diamond City: Nanaimo - The Victorian Era. (Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2002), 15.

2. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 16.

2. Ki-et-sa-kun

1. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 36.

3. The Age of Coal

1. Lynne Bowen, Three Dollar Dreams. (Lantzville: Oolichan Books, 1987), 45.

2. Bowen, Three Dollar Dreams, 59.

4. The Settlers Arrive

1. E. Blanche Norcross, Nanaimo Retrospective: The First Century. (Nanaimo: Nanaimo Historical Society, 1979), 30.

2. Bowen, Three Dollar Dreams, 73.

3. Bowen, Three Dollar Dreams, 60.

4. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 104.

5. The Bastion

1. Jan Peterson, Hub City: Nanaimo 1886-1920. (Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2003), 20.

2. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 30.

3. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 54.

6. Settler Life

1. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 83.

2. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 84.

7. America's Special Relationship

1. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 98.

2. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 117.

3. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 144.

8. The End of Coal

1. Jan Peterson, Harbour City: Nanaimo 1920-1967, (Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2005), 29.

2. Peterson, Hub City, 10.

3. "BC's Worst Coal Mining Disaster." From the Islander. July 27 2010. Online. Accessed July 10, 2017. http://victoriahistory.ca/blog/2010/07/b-c-s-worst-coal-mining-disaster.

4. Peterson, Harbour City, 29.

5. Andrew Farris, "Coal Mining in BC", Energy BC, March 2017. Online. Accessed July 10, 2017, http://energybc.ca/coalmining.html.

9. The Fisheries

1. Peterson, Hub City, 169.

2. Peterson, Hub City, 169.

3. Peterson, Hub City, 170.

4. Eric Keen. "BC Whaling." February 2014. Accessed July 10, 2017. https://rvbangarang.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/bcwhaling.pdf

5. Peterson, Harbour City, 112.

10. The Rise of Forestry

1. Peterson, Hub City, 165.

2. Peterson, Harbour City, 112.

3. Peterson, Harbour City, 154.

4. Peterson, Harbour City, 152.

5. Peterson, Harbour City, 156.

11. The Ferry Struggle

1. Peterson, Hub City, 32.

2. Peterson, Hub City, 36.

12. The Princess Ships

1. Peterson, Harbour City, 114.

2. "Before 1960: Origins." British Columbia Ferries Commissioner. Online. Accessed July 12, 2017. http://www.bcferrycommission.ca/faqs/about-bc-ferries/up-to-1960/.

13. Towards the Future

1. "Maffeo Sutton Park… the last 65 years... " City of Nanaimo, 2015. Online. Accessed July 5, 2017. https://www.nanaimo.ca/assets/Departments/Parks~Rec~Culture/Parks/Maffeo%20Sutton%20Park%20Timeline.pdf.

2. "The First Race." Loyal Nanaimo Bathtub Society. Online. Accessed July 5, 2017. http://www.bathtubbing.com/championship-race/history/first-race

Bibliography

"B.C.'s Worst Coal Mining Disaster." From the Islander. July 27 2010. Online. Accessed July 10, 2017. http://victoriahistory.ca/blog/2010/07/b-c-s-worst-coal-mining-disaster.

"Before 1960: Origins." British Columbia Ferries Commissioner. Online. Accessed July 12, 2017. http://www.bcferrycommission.ca/faqs/about-bc-ferries/up-to-1960/.

Bowen, Lynne, Three Dollar Dreams.Lantzville: Oolichan Books, 1987.

Farris, Andrew, "Coal Mining in B.C.", Energy BC, March 2017. Online. Accessed July 10, 2017, http://energybc.ca/coalmining.html.

Keen, Eric. "B.C. Whaling." February 2014. Accessed July 10, 2017. https://rvbangarang.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/bcwhaling.pdf

"Maffeo Sutton Park… the last 65 years... " City of Nanaimo, 2015. Online. Accessed July 5, 2017. https://www.nanaimo.ca/assets/Departments/Parks~Rec~Culture/Parks/Maffeo%20Sutton%20Park%20Timeline.pdf.

Norcross, E. Blanche. Nanaimo Retrospective: The First Century. Nanaimo: Nanaimo Historical Society, 1979.

Peterson, Jan. Black Diamond City: Nanaimo - The Victorian Era.Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2002.

Peterson, Jan. Harbour City: Nanaimo 1920-1967. Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2005.

Peterson, Jan. Hub City: Nanaimo 1886-1920.Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2003.

"The First Race." Loyal Nanaimo Bathtub Society. Online. Accessed July 5, 2017. http://www.bathtubbing.com/championship-race/history/first-race