Walking Tour

Life in Early Nanaimo

How We Got Here

By Andrew Farris

In this walking tour we will step into Nanaimo's early history, seeing what life was like for the people who lived here from the 1850s to the 1920s. It begins with the early settler days and the town that grew up around the tiny cluster of log cabins and warren of mine shafts that ran under downtown and the surrounding areas.

As more immigrants came and the community grew, people embarked on all sorts of efforts to improve the city. In the 1860s and 1870s libraries, schools and a fire department were set up. New businesses sprang into being along Commercial Street and Victoria Crescent to better serve Nanaimo's inhabitants—including a huge variety of pubs and saloons. At this time democratic self-government was set up, too (though to our eyes these halting early efforts might seem somewhat comical).

All along the way we will see the immense challenges these pioneers faced in laying the foundations for the city we know today.

This project is possible with the generous support of the Nanaimo Hospitality Association and the Petroglyph Development Group of the Snuneymuxw First Nation. We would also like to thank the Nanaimo Archives and Nanaimo Museum for use of their historic photo collections and providing research assistance.

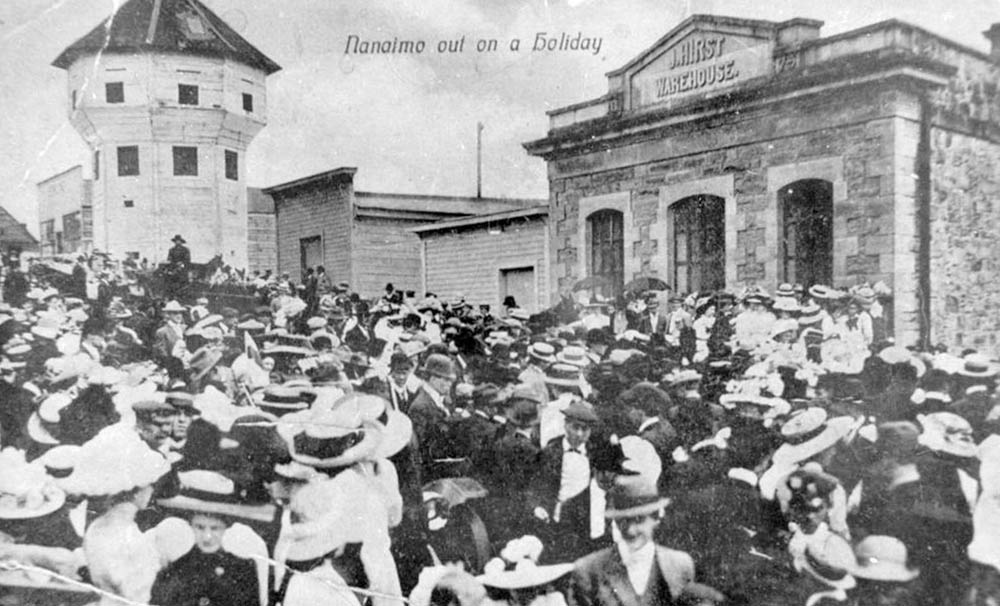

1. Remembering the Pioneers

A postcard view of Nanaimoites congregating in front of the Bastion for a public event. Everyone alive today was born into developed society and it is easy to forget the incredible difficulties faced by those first pioneers who, in a few short years, turned a tiny clearing in the forest into a bustling town.

* * *

"With the present standard of living we enjoy, there is a tendency to forget those who paid the price of opening up this community - those who sacrificed and toiled to build our roads, schools, hospitals and other social institutions which make life easier and more pleasant today. We tend to overlook the contribution of those who worked in the mines, the logging camps, and the early farm settlements."1

2. Simple Beginnings

Nanaimo Community Archives 2000 032 A-P3

1890

The whitewashed bastion stands on its old location bristling with cannons, across the street from where it is today. It was moved a few years after this photo was taken. Behind are some of the simple duplexes built for the first miner-colonists who arrived in the 1850s. Isolated from the outside world, early Nanaimoites lacked almost all the creature comforts modern society takes for granted.

* * *

Given these conditions it's no surprise that the Hudson's Bay Company struggled to get miners in Britain to sign up for this tough life at the edge of the world. In 1862 the HBC's Chief Factor Alexander Dallas wrote a piece for the London Times trying to entice men to come out to Nanaimo. "This is not the country for broken-down gentlemen or 'swells'... Single men can generally rough it out, and the restaurants, generally kept by Frenchmen, are far better than they are in London."2

The colony's governor James Douglas didn't try to sugarcoat the quality of the restaurants (or lack thereof). "The first settlers in this country will have many difficulties to contend with," he wrote. "First the scarcity and quality of food, the want of society, exposure to the weather, and generally the absence of every thing like comfort."3

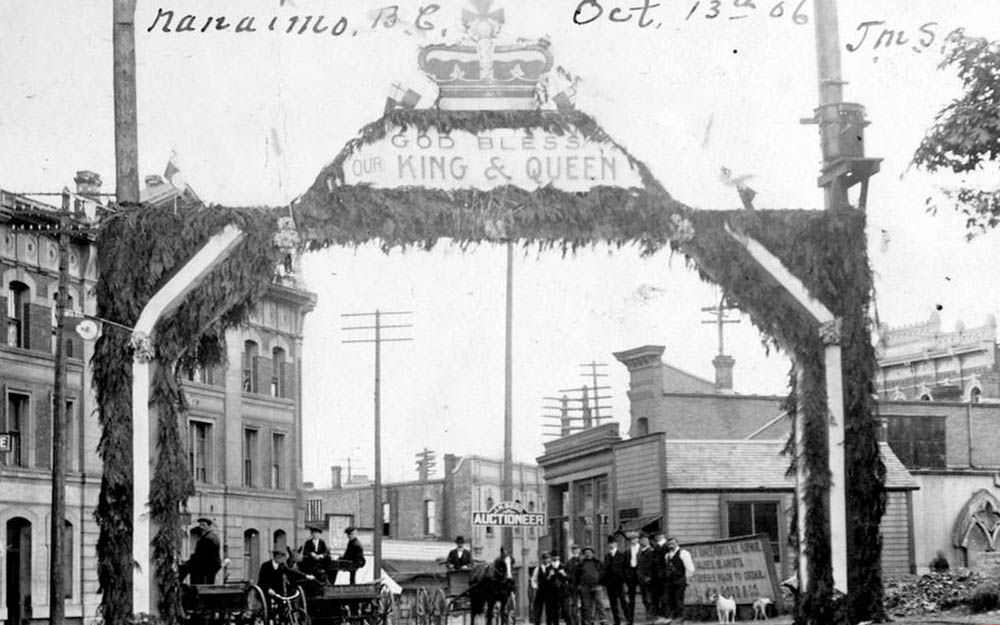

3. Founding a Government

1906

In this view up Chapel Street an evergreen covered arch commemorating the King and Queen of Britain has been erected to mark the visit of some dignitary, possibly the Governor General. As a British colony, and later a part of Canada (a Dominion and only quasi-independent from Britain), B.C.'s government developed along British lines.

* * *

Nanaimo - and the province's - government were gradually built along British lines, yet these early attempts at self-government were haphazard. In 1856 governor James Douglas was given a vague directive from London to set up a legislative assembly for Vancouver Island. Douglas had grown used to ruling the colony himself and was "utterly averse to universal suffrage, or making population the basis of representation."2

Eight ridings were set up and Vancouver Island's first election was held on July 22, 1856. Douglas had until recently administered the colony for the HBC and he wanted to ensure the Company stayed in control. Thus he limited voting to British males who owned 20 acres of land, an absurdly high bar. Only a couple dozen people in the entire colony met the requirements and it just so happened that almost all of them worked for the HBC. In Nanaimo there was only one voter: the HBC's chief factor Captain Charles Edward Stuart.3

The second election in 1859 is remembered as the 'one vote election'. The franchise had been expanded by then so there was now more than one eligible voter in Nanaimo, but the returning officer Dr. Alfred Benson failed to tell anyone when or where nominations would take place. On nominating day Captain Stuart was the only person to show up. He nominated John Barnston, and because Barnston stood unopposed he was duly announced winner of the election.

Word was sent to Victoria, but when the other members of the assembly learned of the circumstances surrounding Barnston's election they refused to accept him. Governor Douglas, weary of all this democratic nonsense, grew impatient and demanded someone in the room to volunteer to represent Nanaimo. When Augustus Rupert Green stepped forward he was appointed on the spot.

Nobody in Victoria bothered to tell anyone in Nanaimo about any of this and in the meantime the citizens of Nanaimo hadn't been idle. They were outraged that they'd missed the nominations and demanded a new vote. They elected the popular Captain John Swanson. Swanson however wasn't even there and was shocked when he learned he had been elected to the legislature. He wanted nothing to do with it and refused to take his place. The exasperated people of Nanaimo were planning another election when word finally reached came from Victoria that Douglas had simply appointed Green to represent them some weeks before. Green served for a year before popular discontent with him led to a new election.4

4. Workers Unrest

Nanaimo Community Archives 2013 010 A-P6

1913

This photo shows militia troops on Chapel Street staging a show of force for striking miners. This incident was the most dramatic in Nanaimo's long history of strained labour relations. The great majority of Nanaimo's early immigrants were miners from Britain's coalfields who had a deeply held tradition of organizing and agitating against unscrupulous mine owners.

* * *

These contracts gave the HBC enormous power over the lives of the miners and their living conditions. Unfortunately the miners found life on 'Vancouver's Island', as it was then known, did not live up to the advertisements they'd seen in England and they chafed under the heavy-handed rule of the Company. Almost immediately there were bitter feuds with the Company's overseers, followed by strikes and desertions as disillusioned miners got in canoes and paddled away, sometimes winding up at American mining camps in the Puget Sound.

The malcontented miners posed tremendous management problems for the HBC and - perhaps fed up with their unruly employees - the company abandoned mining altogether, selling all their assets to the Vancouver Coal Company in 1862. After that other mining companies started up around Nanaimo, but they often fared little better negotiating with their employees and keeping the mines open. The 1913 strike, pictured above, required a dramatic military intervention to get the miners back to work. We will discuss it in more detail in the Dunsmuirs Walking Tour.

Into the 20th Century, Nanaimo was relatively unique in the province for having huge numbers of industrial workers clustered in a single industry in a single location. Thus Nanaimo became a hotbed for union activity, labour activism and left-wing politics, a reputation it has maintained to this day.

5. The Pioneer Women

1920s

Two women crossing Commercial Street in front of the imposing National Land Building, a bank completed in 1914. In its early years Nanaimo's population was heavily skewed towards men, but gradually women arrived, starting families and making the place a real community.

* * *

In Victorian-era Nanaimo, while the men went down into the mines, the women were expected to tend to the homestead. In an age before home appliances this might include a dizzying array of tasks: scrubbing laundry, tending gardens, milking cows, mending clothes and preparing meals. When money was tight they'd often be expected to set up a home cottage industry, making soap, candles, and jams for sale at farmers markets. This all came on top of raising children, of which there were many: In 1871 the average Canadian woman had seven children.1

Always hanging over these women was the threat of widowhood if their husbands were killed in the frequent mine accidents. One of Nanaimo's first teachers, May Needham, remembers arriving in Nanaimo after the 1887 mine explosion that killed 150 miners. All the women wore black for mourning because practically all had lost someone they loved.2

6. Nanaimo Gets a Library

Nanaimo Community Archives 1992 003 C-P13

1951

This building housed the Nanaimo Mechanics Institute, the city's first real library. When it opened in 1864 it was the biggest building in Nanaimo and also served as a social gathering place. Financial troubles meant it soon had to close down and was transformed into the City Hall.

* * *

When construction on the Institute began the new colonial governor, A.E. Kennedy, made his first visit to Nanaimo to lay the cornerstone. It was a jubilant occasion: the city had been decorated with street arches, bunting and flags. Practically the whole town turned out for the procession up Bastion Street to the site you're standing now where he was greeted by four First Nations constables in dress uniform. After much pomp and ceremony he placed the first stone.

When completed the bottom floor served as a social gathering area for galas and soirees, while the upstairs housed the library.

The library was not paid for through taxes, but by a $0.50 a month subscription fee for users. It was popular but evidently not popular enough, as it ran into financial difficulties and in 1886 the building was sold to the municipal government to serve as city hall. The books themselves were dispersed. A new library wasn't built until 1919, when the B.C. Libraries Act was passed and the government began funding libraries for communities across the province.1

This building would serve as city hall until the 1950s, and this picture was taken in its last days before its demolition.

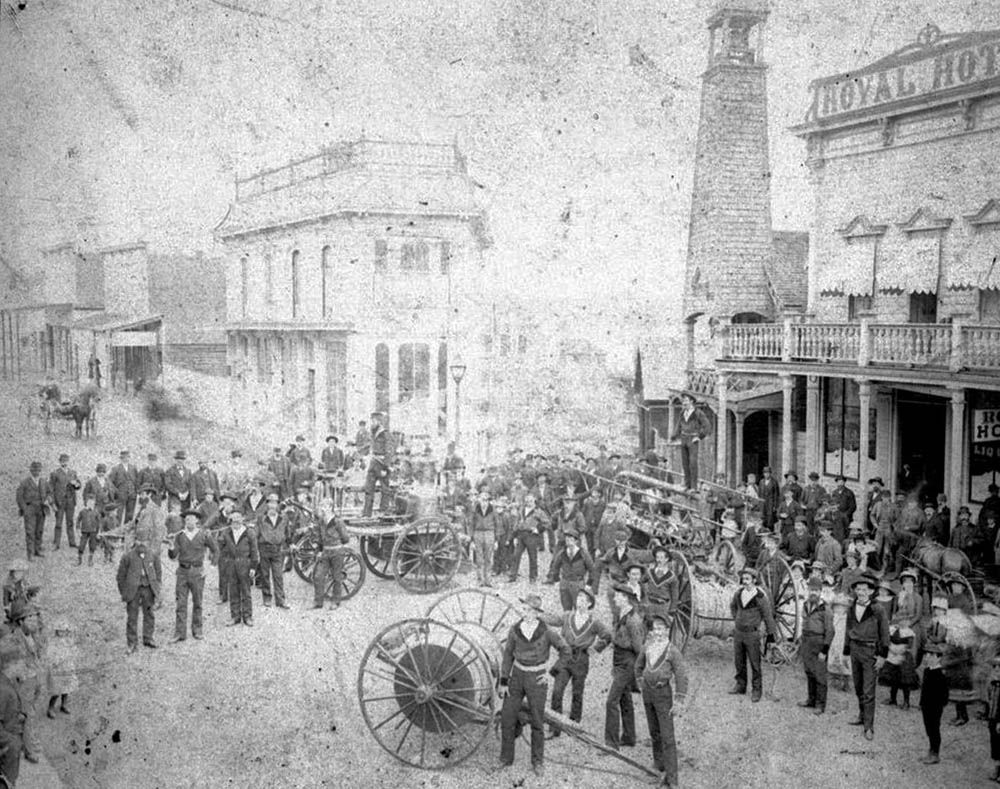

7. The Black Diamond Fire Company

1896

By the 1870s Nanaimo was getting big enough to need a real fire department. Harnessing the growing community spirit, a fundraising campaign was launched to raise money for a fire engine with the slogan "Strive to Save". In this photo we can see the volunteer fire fighters celebrating the purchase of their new equipment in front of the fire hall.

* * *

With the successful public subscription campaign the new fire department was able to buy a pump engine affectionately known as Able Willy and some hose from the Portland Fire Department for $1,100. The fire department quickly became a prominent fixture of life in town, and the crews would often travel to other cities in the Pacific Northwest to compete in hose reel competitions (which they sometimes won).1

Community subscriptions continued to help the department purchase more equipment - such as an 1893 campaign by the Ladies Committee to buy ladders - and to build a new fire house on Nicol Street. As that fire house was being built in 1893 their old fire house just across from where you are standing ironically burned down, along with the adjacent Royal Hotel.2

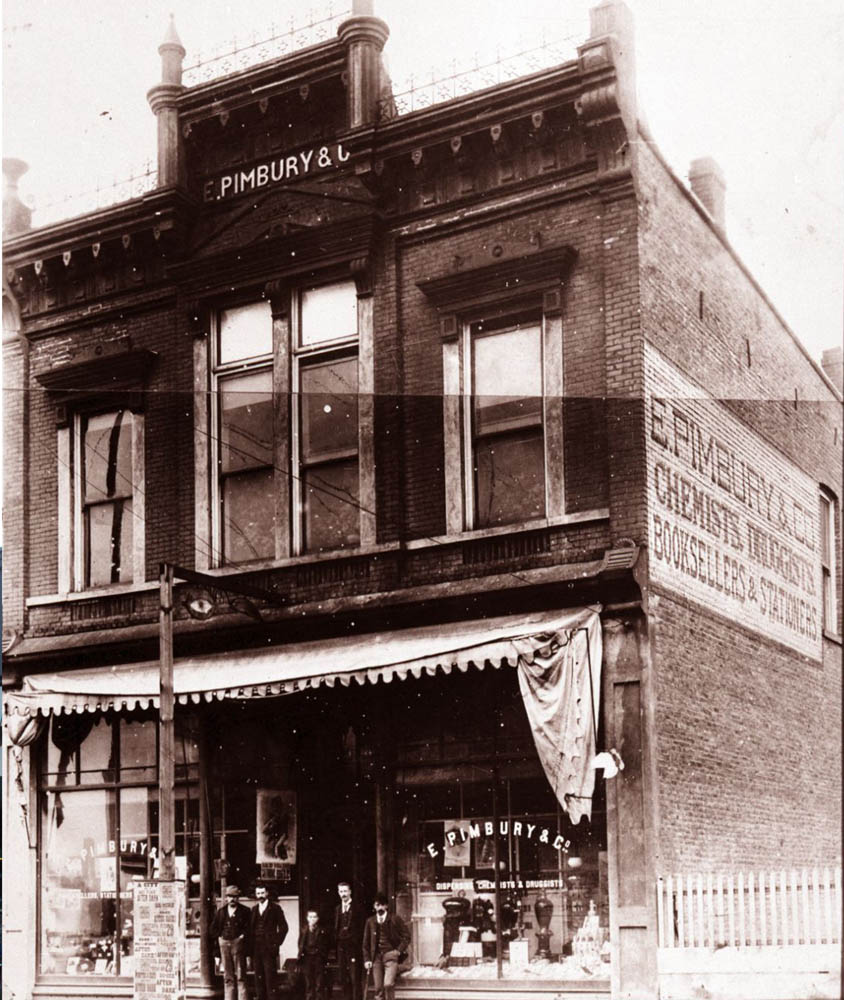

8. The Druggists

1890s

Several people stand in front of Pimbury & Co, probably Mr. Pimbury and his boys. The building has since been replaced but the new facade clearly refers back to the original historic one. People relied on drug stores for all sorts of treatments and cures, many of them concocted by the pharmacists themselves.

* * *

As a contributor to the book Nanaimo Retrospective wrote, this was a "romantic" time for the field. "A period of practice identified with three-tiered decanters of coloured water adorning the front windows and huge posters acting as backdrops advertising panaceas of all kinds."1 Some of these were not as respectable as one would hope: one example is Hamlin's Wizard Oil, which was hawked by travelling troupes of performers. Hamlin, a former magician with a flair for the dramatic, claimed his oil could cure literally everything: "There is no Sore it will Not Heal, No Pain it will not Subdue." Since the oil was essentially just very strong alcohol, Hamlin eventually got into legal trouble when people discovered it didn't, in fact, "permanently kill cancer."2

Edwin Pimbury was one more expert practitioner of pharmacology. Born in Edinburgh, he sailed for Victoria in 1856 and apprenticed there as a pharmacist until 1882, when he set out on his own to Nanaimo and opened this store. The mortars and pestels mounted on the cornice at the top of the building represent the tools of his trade. He kept a garden where he grew and prepared many of the herbal remedies he sold. Pimbury rose high in the community's esteem and was elected to the legislature to represent Nanaimo twice after he retired in 1892.

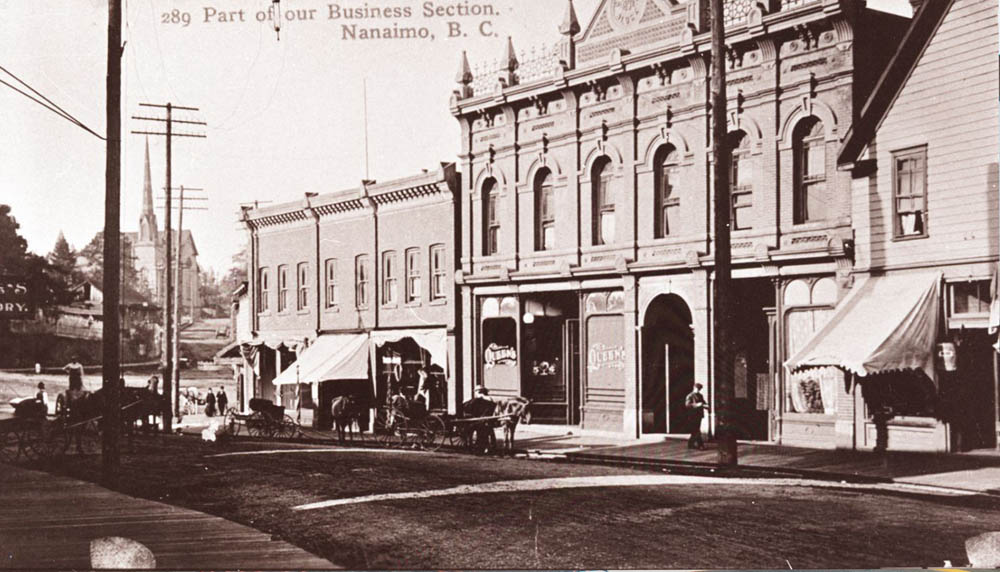

9. Getting Around

Nanaimo Community Archives 2001 026 A-PC3

1890

This photo shows horse drawn carts on Commercial Street. Horses remained essential to getting around in early Nanaimo's muddy, unpaved streets. They couldn't go very far outside the city because it took decades for proper roads to be hacked through Vancouver Island's thick forests.

* * *

A whole range of businesses sprang up around town to feed and shoe the horses and keep them in good health. The expense of keeping horses meant that they were out of reach for the majority of people. It was no surprise then that Nanaimoites met the first arrival of a contraption called the bicycle with great excitement. The "machines", as the Nanaimo Daily Free Press called them in the 1890s, were a more democratic means of transportation because most people could afford them.1

Cars would come later, with the first cars appearing in Nanaimo in the 1910s, but not really becoming popular until the 1920s. Paving of the muddy roads seen in the above photo actually occurred surprisingly late, after the First World War. The highways leading out of Nanaimo took even longer. One man recalled the experience of riding a Vancouver Island Coach Line bus towards Courtenay in 1930s:

"The roads were rough, then; the buses primitive. Short stretches of blacktop soon gave way to a gravel surface which, in turn, as the buses rolled farther northwards, became a dirt track. As one driver pungently observed, 'even the potholes had potholes.' Under these conditions, it didn't take long for the sturdy vehicles to squeak and shake. Buses, in those beginning days, were mostly converted trucks or made-over, extended cars."2

10. Schooling

1920s

This is a shot of a very busy day on Commercial Street, with Spencer's department store looming in the background. You can see a number of children out and about - not in school. Proper schooling took some time to get off the ground in Nanaimo, with the first purpose-built school only opening on Crace Street in the 1870s. In an age before compulsory education and child labour laws, Nanaimo kids were often pulled out of school early to work in the mines.

* * *

Nevertheless as the population grew and people gradually began to realize the importance of an education, the school became crowded and more were built. Miss May Needham, one of Nanaimo's best known teachers around the turn of the century, had to handle a class of 90 boys crammed onto long benches cafeteria-style. One contributor to Nanaimo Retrospective wryly noted that "It requires little imagination to appreciate the teacher's difficulties."2

Even as more schools were built and progressive policies like combining boys and girls into single classes were enforced, some conservative practices held fast: At the first co-ed school the boys and girls spent recess in different playgrounds separated by a tall fence. Another practice which seems odd to modern eyes continued well into the 20th Century: that of "having having pupils line up outside in good weather, or in the basement in wet weather, and march to their classrooms, carried out to the beat of a drum."3

11. The Pub Scene

1890s

In this photo we're looking down Victoria Crescent. At the middle is the Palace Hotel, which has changed relatively little over the last century. Saloons and bars, often attached to hotels, were hugely popular places for rowdy miners to let off steam after long days spent underground. At one point there were 28 bars or saloons serving a population of less than 10,000.1 That's more than serve the city's 90,000 residents today.

* * *

A pint cost a mere five cents as late as the 1920s (fifty cents in today's money) and several local breweries, like the Union Brewery which was located where the city hall is today, cranked out thousands of gallons of beer to keep the city supplied. It was believed that beer was good for a miner's health as it would wash down the coal dust, which heightened the appeal in Nanaimo. A common promotion was to offer men still in mining clothes their first drink on the house. As one observer later recalled, it was an effective tactic:

"You don't know how much they just used that for an excuse. I can't speak highly enough of the type of person that the coal miner was. There were a great deal of Scotchmen and Welshmen here and they were fine, thrifty people. They were honest as the day is long and the only trouble was that they perhaps liked their beer a little bit too much.

"When I was a little chap I can see them now. Coming home so drunk they couldn't hang on to the fence. Matter of fact, our neighbour across the street was literally so intoxicated he couldn't hang on to the pickets of the fence. It was tragic, because when he was sober he was a good father, a good husband and a good provider. But this did occur periodically and that's where the money would go. I think drinking to that intensity has gone out."3

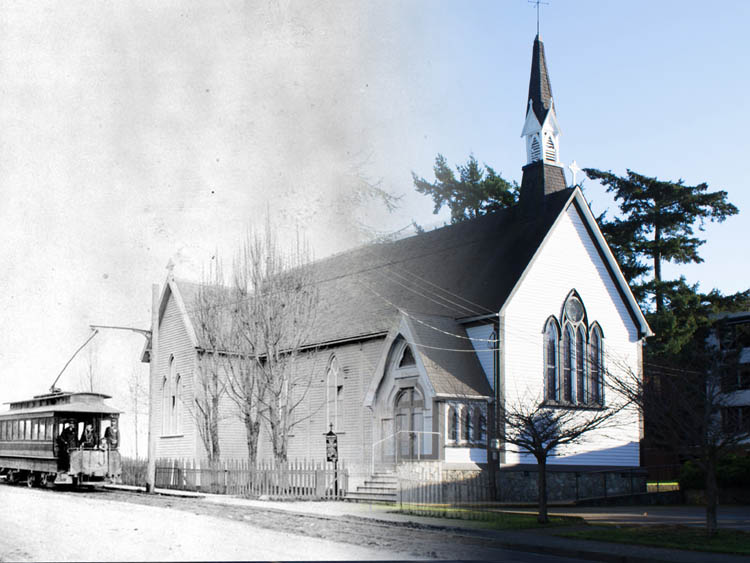

12. Religious Life

1890s

Looking across Nicol Street we see a butcher and beyond that a church. Churches were a major fixture of life at this time. While the miners may have indulged at the bars and saloons, most also prayed at one of Nanaimo's Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist or Catholic churches.

* * *

Another group was the Temperance movement, which sprang out of the desire to ban alcohol. Alcohol was often cited as a driver of poverty: working husbands often frittered away all his pay on drink leaving nothing for his family. It was also associated with domestic violence. The temperance movement did succeed in having alcohol banned in 1916, but the scheme was largely a failure as prohibition was hardly enforced. The prohibition law was repealed a few years later.

Endnotes

1. Remembering the Pioneers

1. Blanche Norcross. Nanaimo Retrospective: The First Century. (Nanaimo: Nanaimo Historical Society, 1979), ix.

2. Simple Beginnings

1. Jan Peterson, Black Diamond City: Nanaimo in the Victorian Era. (Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2002), 65.

2. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 98.

3. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 35.

3. Founding a Government

1. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 118.

2. Maureen Duffus. "Vancouver Island's First Legislature." Colonial History Vancouver Island. Online. Accessed July 3, 2017. http://www.maureenduffus.com/history/first-legislature.php

3. Duffus, Colonial History Vancouver Island. Online.

4. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 117.

4. Workers Unrest

1. Norcross, Nanaimo Retrospective, 31.

5. The Pioneer Women

1. "Facts and Figures: Canadian Birth Rates." uOttawa Medicine. Online. Accessed June 20, 2017. http://www.med.uottawa.ca/sim/data/birth_rates_e.htm

2. Norcross, Nanaimo Retrospective, 50.

6. Nanaimo Gets a Library

1. Norcross, Nanaimo Retrospective, 50.

7. The Black Diamond Fire Company

1. William Barraclough. "Early Days of Wharf and Front Streets with the intersection of Bastion Street, Nanaimo." Transcribed recording on July 13, 2015. Online. Accessed June 20, 2017.

https://viurrspace.ca/bitstream/handle/10613/201/NanaimoHistoryBarraclough16.pdf?sequence=3

2. Peterson, Black Diamond City, 149

8. The Druggists

1. E.C. Alft, "Chapter 7", Elgin: Days Gone By, Online. Accessed August 1, 2017. http://www.elginhistory.com/dgb/ch07.htm

2. Norcross, Nanaimo Retrospective, 119.

9. Getting Around

1. Norcross, Nanaimo Retrospective, 75.

2. Norcorss, Nanaimo Retrospective, 77.

10. Schooling

1. Norcross, Nanaimo Retrospective, 42.

2. Norcross, Nanaimo Retrospective, 44.

3. Norcross, Nanaimo Retrospective, 45.

11. The Pub Scene

1. Lynne Bowen. Boss Whistle: The Coal Miners of Vancouver Island Remember. (Lantzville: Oolichan Books, 1992), 213.

2. Bowen, Boss Whistle, 213.

3. Bowen, Boss Whistle, 213.

4. Bowen, Boss Whistle, 215.

Bibliography

Barraclough, William. "Early Days of Wharf and Front Streets with the intersection of Bastion Street, Nanaimo." Transcribed recording on July 13, 2015. Online. Accessed June 20, 2017.

Bowen, Lynne. Boss Whistle: The Coal Miners of Vancouver Island Remember. Lantzville: Oolichan Books, 1992.

Duffus, Maureen. "Vancouver Island's First Legislature." Colonial History Vancouver Island. Online. Accessed July 3, 2017. http://www.maureenduffus.com/history/first-legislature.php

"Facts and Figures: Canadian Birth Rates." uOttawa Medicine. Online. Accessed June 20, 2017. http://www.med.uottawa.ca/sim/data/birth_rates_e.htm

Norcross, Blanche. Nanaimo Retrospective: The First Century. Nanaimo: Nanaimo Historical Society, 1979.

Peterson, Jan. Black Diamond City: Nanaimo in the Victorian Era. Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2002.