Walking Tour

Robert Dunsmuir in Nanaimo

Captain of Industry or Robber Baron?

By Andrew Farris

This tour tells the story of Robert Dunsmuir, one of the most remarkable rags-to-riches stories in Canadian history. Dunsmuir came to British Columbia from Scotland as a lowly indentured miner for the Hudson's Bay Company in 1851. He quickly proved himself a tireless and loyal worker who rose rapidly to manage coal mining operations in Nanaimo.

In 1870 he set out to start his own mining company and before long he had quashed the already well-established competition. Using shrewd business tactics and ruthless cost-cutting—often at the expense of the well-being of his miners—he quickly became the richest man in the province.

By the 1880s when he built the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway, he was envied by the rich as a captain of industry beyond peer. The poor and working classes on the other hand, despised him, seeing him as a robber baron. However, even his harshest critics admitted a grudging respect for the man who manifested the virtues of hard work and initiative.

After his sudden death in 1889 his family bickered over his vast empire, and under their stewardship it soon crumbled into dust. A fascinating individual, Robert Dunsmuir remains the most controversial figure in British Columbia's history, and one who left an indelible mark on Nanaimo.

This project is possible with the generous support of the Nanaimo Hospitality Association and the Petroglyph Development Group of the Snuneymuxw First Nation. We would also like to thank the Nanaimo Archives and Nanaimo Museum for use of their historic photo collections and providing research assistance.

1. Scottish Beginnings

Nanaimo Community Archives 2012 006 A-PC1

1915

This photo from 1915 shows the Duke of Connaught, the Governor General of Canada, and his wife at the Nanaimo courthouse. When a young Robert Dunsmuir left Scotland as an indentured miner for the Hudson's Bay Company, he couldn't have been further away from this high society. But Robert and his wife Joan had sky high ambitions and relentless drive. One day they would be the ones entertaining governor generals.

* * *

Robert and Jean could take some little comfort that their grandfather left behind enough money to see them taken care of. Robert, now aged 10, went off to attend a mining academy. So many family tragedies compressed into his short childhood must have had a devastating effect on the boy, but he emerged from them a serious man possessed of steely determination.

In 1847 Robert married his sweetheart Joanna Oliver White, who gave birth to their first daughter eight days later. It would not be long before destiny came knocking. Robert's uncle, a miner named Boyd Gilmour, had been recruited by the Hudson's Bay Company to help develop coal mines at Fort Rupert on the northeast tip of Vancouver Island.

It's unlikely Robert or Joan had ever heard of Vancouver Island before. Separated from Europe by a six month sea journey around the southern tip of South America, the Pacific Northwest was one of the last blank spots on the world map. It remained practically free of European settlement.

Yet when Gilmour offered Robert the opportunity to join him as an indentured miner for the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) at this remote encampment at the end of the world, he deliberated less than a week before accepting the offer.

Legend has it that Joan agreed to go on the condition that Robert built her a castle in the New World. It was a promise he would not live long enough to see fulfilled.

2. Fort Rupert

1930s

This is the last of the primitive log duplexes that housed the first miners in Nanaimo. It's in the process of being demolished in this picture from the 1930s. Robert and Joan lived in a cabin similar to this when they arrived in Fort Rupert. When they moved to Nanaimo less than a year later they first lived in a cabin identical to this one just south of where you are standing.

* * *

Dunsmuir and the handful of other British miners were there to manage some 800 Kwakiutl First Nations people who dug for coal located just below the surface in exchange for blankets.2 Dunsmuir quickly distinguished himself for his unimpeachable work ethic, continuing to work while the other British miners grumbled and went on strike. However repeated failures to find good underground coal seams would soon spell the doom of the entire Fort Rupert project.

For Joan and the children it was a difficult life. The fort was largely cut off from the outside world, save for the occasional ship that took off coal and brought in precious supplies. They lived in a small log cabin and grew what food they could, while trading with the First Nations for fish and game. The few dozen settler-miners were outnumbered by thousands of Kwakiutl First Nations who lived alongside them.

The settler-miners were sometimes bewildered by the behaviour of the locals, including one episode that passed into Dunsmuir family lore: The Kwakiutl "demonstrated their different cultural values by once kidnapping James Dunsmuir for several hours," because, writes the historian Lynne Bowen, they were fascinated by the child. "When the baby was found, his benevolent captors attempted to buy him from his frantic parents for sea-otter skins piled 'to the height of a man,' a handsome price indeed."*3

Generally the two sides got along well. As John Helmcken wrote "among these people we walked and roamed and certainly, after having become accustomed to them felt less fear of molestation than I had experienced when traversing the slums of London."4

Less than a year after their arrival the HBC decided to relocate the Dunsmuirs to Nanaimo where far more promising coal deposits had been discovered.

3. Proving his Worth

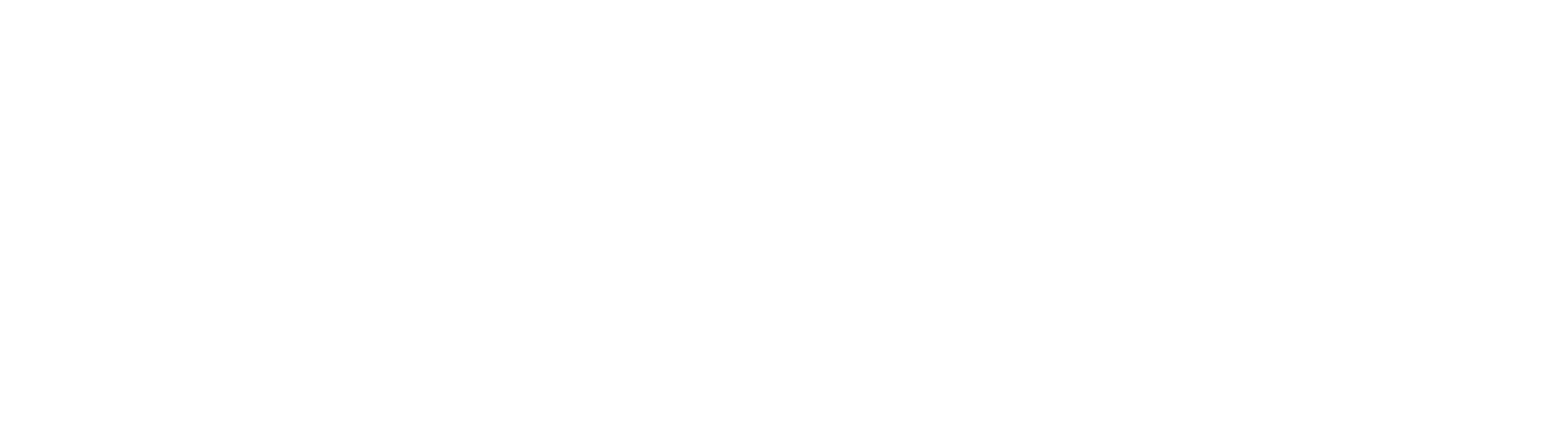

1858

This photo shows an early view of Commercial Inlet in 1858. This will have been what the view looked like out the Dunsmuirs' front porch, as their home was directly behind where you are now standing, across Front Street. You can see the first coal wharf in the foreground. By the late 1850s Robert's success meant he was able to strike out on his own and start his own mine. It was called the 'Level-Free Mine' and located at the head of Commercial Inlet just a few hundred metres to the southwest.

* * *

Joan was determined to push Robert to achieve his utmost and moved with her children into the cabin so as to be close to Robert. As she busied herself raising the kids and attending to the household, she remained Robert's closest confidante and most trusted adviser.

Robert's education at the Scottish mining academy soon proved its worth: He discovered a rich new seam of coal and managed the development of a new pit. He soon gained a reputation for initiative and industriousness, further helped by his refusal to take part in another miner's strike in 1855. Instead he counselled the other miners to keep cool heads and continue work. The HBC rewarded his loyalty by giving him the first contract to work as a free miner and develop his own mine.

Dunsmuir wasted no time in seizing this opportunity, and he began managing a new mine at the head of Commercial Inlet. It was located near the intersection of today's Esplanade Street and Terminal Avenue. In those days Commercial Inlet was much larger and extended all the way to the end of Victoria Crescent. Dunsmuir's 'Level Free Mine' was so-called because it tunneled on an upwards angle into the rocky outcrop allowing water to drain out without need for pumps.

In short order the Level Free Mine's output rivalled the other Hudson's Bay Company pits. By February 1856 the steamer Otter was entirely filled with coal from the Level Free Mine. Importers in San Francisco were immediately impressed and demanded "send us Dunsmuir coal."1

Robert's success meant he was now well placed to take advantage of Nanaimo's next transformation.

4. Mine Superintendent

1860s

In this photo from the 1860s, we see several people standing on the patio of Adam Horne's Hudson's Bay Company store on Wharf Street. The Bastion has since been moved slightly. At right where the walkways are was actually the location of Nanaimo's first shallow coal mines. In 1862 the Hudson's Bay Company sold its mining operations to the Vancouver Coal Mining and Land Company (VCML). The new directors were impressed by Robert and appointed him superintendent of their mines. The store, which was frequented by Robert, became independent.

* * *

The VCML started by shaking up mine management, and Robert was the obvious choice for new mine manager. Robert began by importing a small steam engine, named Pioneer. It was the first steam engine west of Ontario. It was early evidence of Robert's drive to stay on the cutting edge of technology, a trait that paid dividends throughout his career. He oversaw the construction of two huge wharves, completing the work in 1863.1

Now the Pioneer would shuttle back and forth between the pitheads and the wharves, dumping coal into chutes that deposited onto waiting ships. Up to that point the coal had been loaded onto ships by Snuneymuxw women, who took baskets of it in their canoes and paddled out to ships at anchor in the harbour.

Always eager to jump at any new opportunity, in 1864 Robert left the VCML to become manager of the newly formed Harewood Coal Mining Company. They had found promising coal seams a short way inland, around today's University Village Mall.

To mark his departure from the VCML his miners held a Public Testimonial Tea at the Institute Hall at Bastion and Skinner Streets. They had pooled money to present him with a gold watch inscribed "Presented to Robert Dunsmuir by the miners of Nanaimo as a token of respect."

Robert rose to accept the gift and address the crowd: "When I was amongst you I little anticipated this kindness… Or that I had gained so much of your respect as exhibited towards me this evening, and of which I feel justly proud."2

Given Robert's later reputation, his popularity amongst his men is intriguing. He was then close enough to his days as an indentured miner that he still empathised with the miners and fairly addressed their concerns, making him a popular manager.

This would not last for long.

5. Robert's Great Discovery

Nanaimo Community Archives 2012 012 A

1867

A view of Nanaimo in 1867. The thoroughfare at left is Commercial Street which at that point included a bridge to connect it to Victoria Crescent. The Bastion is at right. Robert had a new home built for his growing family which was located just southwest of where you're standing, at the corner of Albert Street and the street that still bears his name, Dunsmuir.

In 1869 while on a fishing trip north of Nanaimo at a place he would call Wellington, Robert discovered a great seam of coal. He partnered with a naval officer to develop it, marking the beginning of Dunsmuir's business empire.

* * *

Sometimes on his days off Robert would go with his friend Jimmie Hamilton up the rutted trail north to fish in Diver Lake. It was actually Hamilton who liked fishing, Robert preferred to wander off into the woods to search for signs of coal outcrops. In October 1869 he returned from one of these trips in a state of high excitement. He'd found evidence of a rich seam, and what's more it was just beyond the VCML's lease lands: he could claim it for himself.

Starting a mine was an expensive business and Robert needed capital. Luckily there was no shortage of wealthy Royal Navy officers making port calls, and they knew the value of coal—after all, their ships increasingly ran on the stuff. Lieutenant Wadham Neston Diggle agreed to invest in the new venture, and together they formed Dunsmuir, Diggle and Co. Tests found that the coal from Wellington, as it came to be known, performed better in ship's boilers than any yet found in Nanaimo. The Royal Navy wanted all it could get.

Robert got to work, but for over a year he struggled to sink a successful shaft and ran out of money a number of times, though Diggle's navy connections meant there were always rich officers willing to invest and keep the operation going.

Finally in July 1871 he found the perfect outcropping for a mine. Work began in earnest. A shaft was sunk, a wharf was built in Departure Bay, and tracks laid to connect them. His new workers had to walk to work, and so it was necessary to build them homes near the pithead. The little town of Wellington sprang into being, with hotels, bars, stores and churches to serve Dunsmuir's miners.3

Output expanded relentlessly. In 1874 just shy of 30,000 tonnes of coal were extracted, almost all sold to eager buyers in San Francisco. By 1878 the total was 88,000 tonnes, more than produced by the VCML. The next year Robert summarized his operations:"4 3/4 miles of railway; 4 locomotives; over 400 waggons; 4 [hauling] engines and 2 steam pumps; 3 wharves for loading vessels, with bunkers, etc.”4

Wellington was making Robert a very rich man.

6. Crushing the Unions

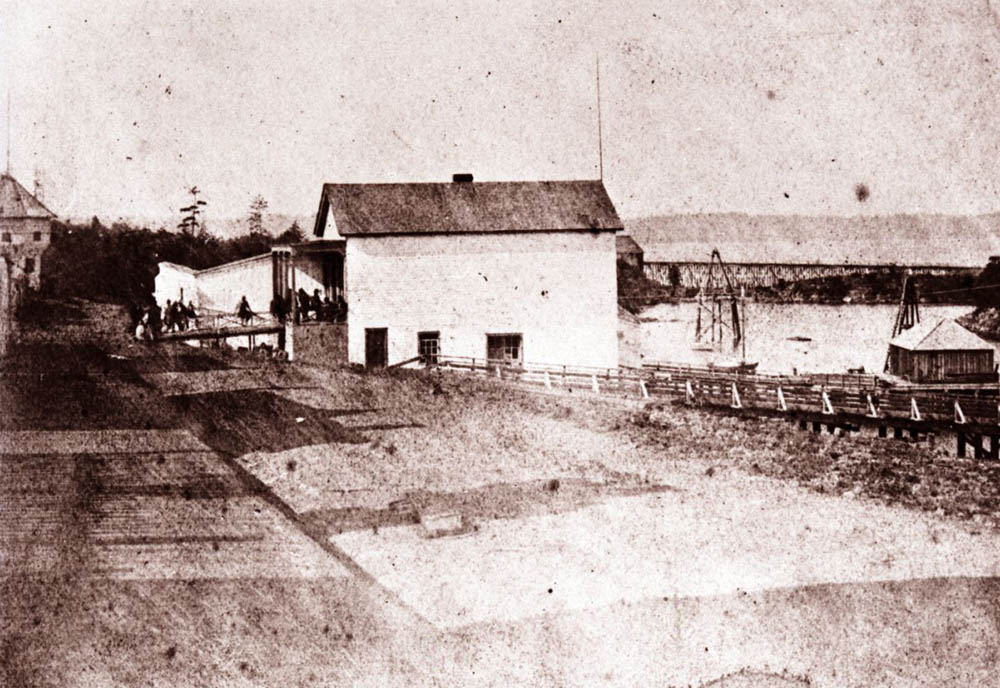

1930s

A fire engine takes part in this May Day Parade on Victoria Crescent in the 1930s. May Day is celebrated as a holiday for workers, particularly by socialists. Robert was extremely hostile to socialists and those who might demand better working conditions. As the mining operations in Wellington grew the miners attempted to unionize, fighting for better wages, better working conditions, and the exclusion of Chinese workers from the mines, who were seen as undercutting the white miners' wages. Robert would have none of it and he ruthlessly crushed a strike in 1877. It began a pattern that would be repeated many times in the years ahead.

* * *

By now Robert's two sons James and Alex were young men being raised in the mining business. The younger Alex was representing his father's business interests in San Francisco. Unbeknownst to his father he was also developing a taste for the drink, and had scandalously moved in with a recent divorcee. Officially she was his housekeeper.

James, now 25, was managing the Wellington mine for his father. He'd been working in mines since he was 16 and had attended a mining academy in the United States, but he lacked his father's managerial talent. In 1877 the miners were exasperated by James' failure to properly address problems with malfunctioning scales. The scales determined how much coal each miner had brought to the surface—and how much they were paid. But James's slow moves to fix the scales was but the latest in a long-simmering list of grievances.

Robert often hired Chinese miners who were willing to work for half the pay of Europeans. About half his workforce was Chinese.2 To Robert, who felt a man should be judged on the quality of his work not the colour of his skin, this was simple business sense. Yet he also cynically used the Chinese to undercut efforts to unionize by white miners. Robert Dunsmuir paid the head tax on the Chinese miners—the racist fee imposed on Chinese immigrants to try and limit their numbers. As a result they were especially beholden to the Dunsmuirs and would not take part in any strikes with the white miners. The year before the pay scales dispute Robert had used the threat of Chinese workers taking their jobs to force a bitterly opposed pay cut upon the white miners.

Now in 1877 the miners had had enough. Dropping their tools, 100 of them went on strike. They went to a pub in Nanaimo and voted to form a union. Robert reacted furiously. He ordered Alex to hire a crew of scab miners in San Francisco. He also posted an open letter in the Nanaimo Free Press which illustrates his domineering attitude towards his mines and the people who worked in them:

"There is an impression in the community that we are obliged to accede to the miners' demands: but for the benefit of those whom it may concern we wish to state publicly that we have no intention to ask any of them to work for us again at any price."3

He publicly threatened to shut his mines entirely if the strikers didn't go back to work, and sent sensational requests to Victoria for military aid. He warned the premier there would be "bloodshed" if the strikers (who had been peaceful) weren't put in their place.4

Eventually a small police force was dispatched to evict the striking miners from their homes at Wellington on Dunsmuir's property. Order was restored and the strike was broken, but this event left a lasting bitter legacy and would set a pattern: every future attempt to unionize would be crushed. Now the miners called him a robber baron.

7. Ardoon

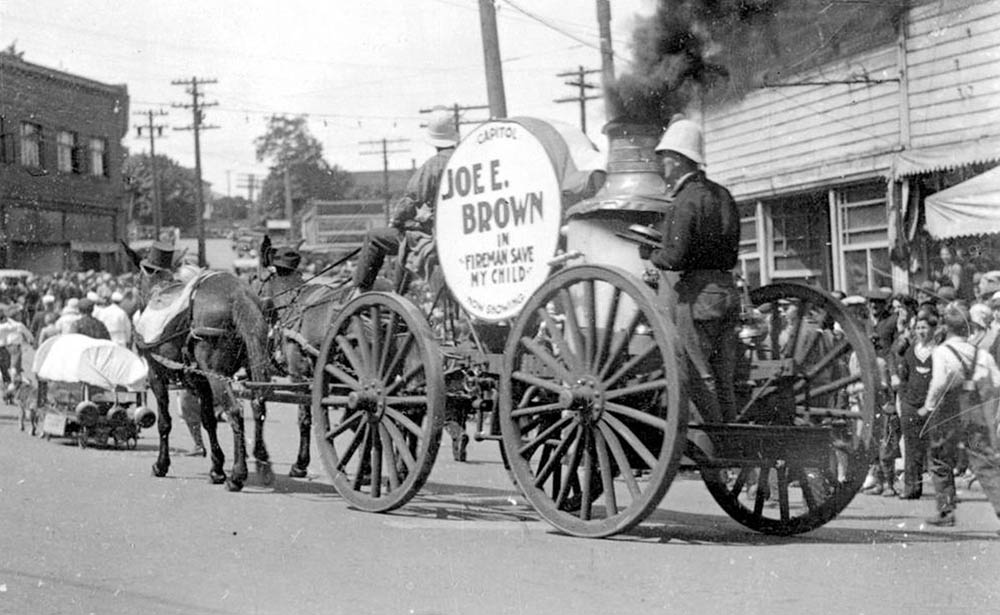

1890s

In 1872 the Dunsmuirs built a spacious new two storey home, the finest in Nanaimo at the time. It was called Ardoon and you can see it in this photo overlooking Victoria Crescent on a winter's day. The Union Brewery is visible behind it. As Robert's wealth and influence grew he became the most prominent and respected man in Nanaimo, a familiar face around town.

* * *

"Joan's strong will and influence over her husband and her family were not apparent to outsiders watching the family's fortunes rise. But inside Ardoon her family knew that she had a vigorous mind and a forceful personality and that she played an important part in her husband's business decisions. She was his only real partner."1

In those days Nanaimo was a growing community, but still small at around 600 people. Given their wealth and prominence it is hardly surprising then that the family came to take on an outsize role in the community. Robert served as a real estate appraiser, a jury foreman, spokesperson for the local member of the provincial legislature, and a founding member of the Total Abstinence Society.

The last position is interesting, because Robert himself never thought he should abstain from alcohol. Only everyone else. He frequently drank rum and whiskey, reportedly to the point of complete drunkenness. Much the same way he handled the miners' strike, he believed he could do as he saw fit. "Like many able men of his time, Robert Dunsmuir believed in one law for himself and another for lesser mortals."2

8. Entering Politics

1890s

This was the site of the Union Brewery, beside Robert Dunsmuir's home of Ardoon and on the street that bears his name. In 1882 Robert chose to enter politics, running to represent Nanaimo in the provincial legislature. He was informed he had won the election in the middle of a great triumphal trip he took across Canada, Europe, and the United States.

* * *

As his stature grew and his reputation spread across British Columbia and the British Empire, he saw an opening to enter into politics. He had always been far more interested in business than politics, but in those days politics did not pay well nor was it usually a full time job. This meant the richest men were well placed to run for office as a sort of side gig. So much the better if they won: they could wield their influence in new ways. This is well illustrated by Robert's first election campaign.

The election of 1882 was to be held in September and Robert had decided to run to represent Nanaimo in the provincial legislature. Yet he had also planned a major international trip to boost his own profile and return triumphantly to his Scottish homeland. He would travel east across Canada by rail, stopping in Ottawa, and then take a steamship across the Atlantic and visit London and Paris. Then he would return via the United States.

He departed on this months-long adventure several months before the election was to take place, and in his absence left the running of his campaign to his sons and son-in-law. In an era before teleconferencing and email, Robert could exercise little control over his own election campaign from abroad—but he didn't seem to care. Nor did it matter. He was informed by telegraph in September that he had won anyway, winning 226 of the 424 votes cast in Nanaimo.3 His reputation amongst the miners who populated Nanaimo was apparently not yet toxic enough to keep many of them from voting for him.

A contented Robert returned shortly after and built a new house in Victoria where he could live part time and take up his seat in the legislature. The house was called Fairview and located just across from the harbour from the legislature. It wasn't quite the castle he had promised his wife all those years ago in Scotland, but that would come soon.

9. Building a Railway

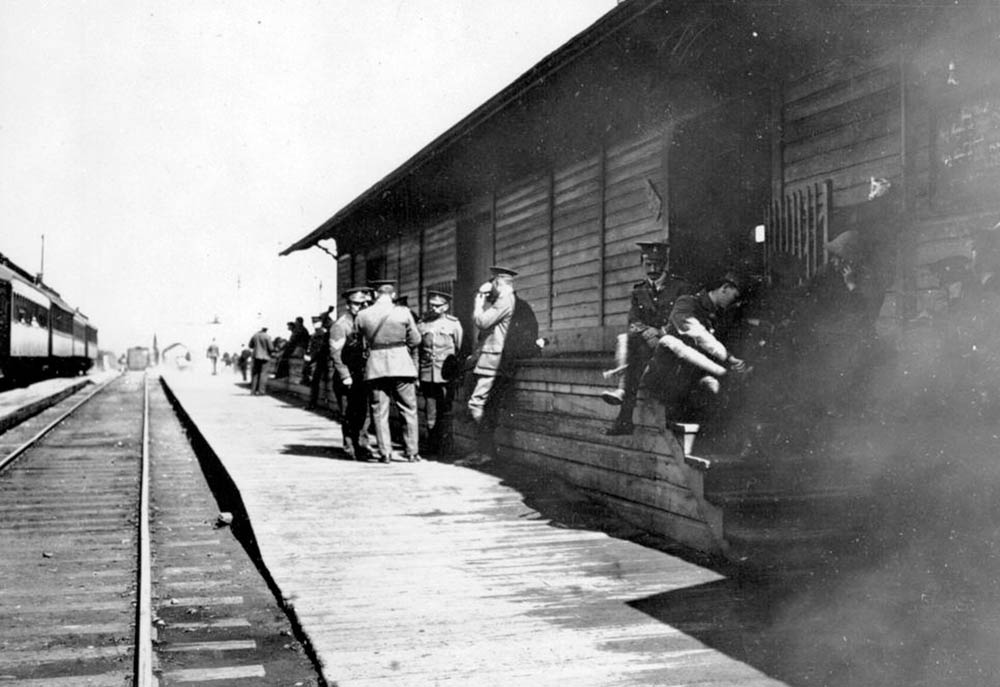

1913

In this photo from 1913, strike-breaking militia troops stand outside the old Esquimalt & Nanaimo railway station (the current building later replaced this simpler one). It is fitting that these soldiers are in Nanaimo to quell a miners' strike decades after Robert's death. In Robert's time the soldiers he needed to put down strikes had to arrive by boat. After Robert secured the contract to build this railway—over the strenuous objections of many in Nanaimo and around the province—strike-crushing soldiers could arrive much faster.

* * *

It is likely that during Robert's trip to Ottawa in 1882 he discussed the outlines of a railway deal with government officials, though if he did he kept it a secret. A year later, with great pomp and ceremony, the Governor General, the Marquis of Lorne, paid Robert a visit at Nanaimo.

The Queen's representative in Canada was the most high profile visitor to Nanaimo up to that point. Crowds turned out to cheer him and the coal magnate as they rode down Commercial Street, which had been decorated with arches and flags for the occasion. They went into Robert's house at Ardoon where the Governor General stayed overnight.

When they emerged the next day Robert announced that he would take on the building of a railway from Esquimalt to Nanaimo. He had driven a very hard bargain. In exchange for taking the contract he would receive a massive subsidy of $750,000. Not only that but he would receive an absolutely enormous land grant stretching 32 km to either side of the railway, all the way from Esquimalt to the Seymour Narrows, north of Campbell River.

Many British Columbians were appalled by these conditions. The land grant was seen as a stunning give-away of the province's natural wealth: two million acres, a fifth of Vancouver Island, and most of the best land for settlement, including all the mining rights therein. Furthermore the railway was initially meant to go all the way up to the Seymour Narrows, but Robert had argued the federal government down to a railway to Nanaimo, half that distance (121 km). This left the burgeoning communities of the Comox Valley and Campbell River out of the loop. Yet the land grant was not reduced and all the land up to the Seymour Narrows would still go to Robert.1

Miners in Nanaimo were also fiercely opposed because they knew that Robert would import thousands of Chinese workers to help build the railway. Once it was completed the workers would settle in places like Nanaimo and compete with white labourers for jobs.

Nevertheless when Robert set his mind to something he pushed through all opposition: on February 26, 1884, construction of the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway began.

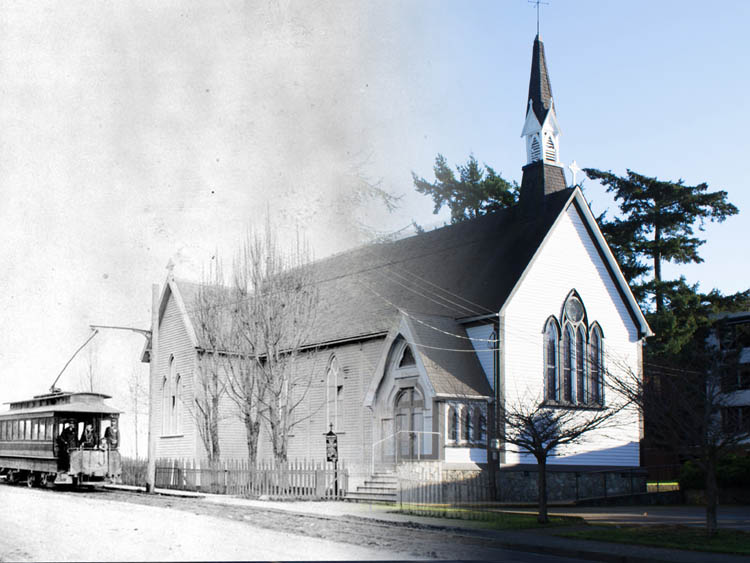

10. The Pinnacle of Power

Nanaimo Community Archives 2013 003 A-P49

1945

In this 1945 photo, a train pulls into Nanaimo's station as people wait on the platform. Completing the railway under budget and ahead of schedule made Robert Dunsmuir a household name in Canada. Finally the work of uniting Canada with a single railway was complete. 35 years after arriving with Joan at ramshackle, windswept Fort Rupert as a lowly indentured miner, Robert had built an astonishingly large business empire.

* * *

Macdonald hammered in a final silver spike to great cheers. The prime minister and the coal magnate got along well, laughing and toasting as they rode Robert's private railcar back to Nanaimo. There they went to celebrate the occasion at the Royal Hotel on Commercial Street, and Macdonald even treated the crowds outside to an appearance on the balcony.

Macdonald then took Dunsmuir up on his offer to view a mine shaft. Donning mining overalls, the two powerful men descended to the bottom of Wellington No. 1 shaft and shared a toast of scotch. Robert was at the pinnacle of his career.

He was far and away the richest man in the province and a household name across Canada. In 1887 he was appointed President of the Executive Council of the BC government, making him effectively the second most powerful person in provincial politics after the premier. There was also discussion of a knighthood in time for Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee that year. And at long last he began construction of the castle he had promised his wife Joan back in Scotland almost 40 years before. Craigdarroch Castle would be the most opulent home in all of British Columbia, and is today a museum and national historic site. Yet Robert would not live to see the castle completed.

11. Robert's Death

1893

A crowd has gathered for the ceremonial laying of the cornerstone of the St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church. This church featured in a play about the Dunsmuirs written by Rod Langley called Alone at the Edge. Soon after reaching the pinnacle of power Robert died suddenly in 1889, setting the stage for a vicious and protracted family battle over his estate.

* * *

During question period in the legislature the member for Comox asked Robert when he was going to extend the railway to Comox. Robert gave the kind of 'I will do as I see fit' reply that is reminiscent of his treatment of the striking coal miners in 1877. Replying in his capacities as both president of the executive council and president of the railway company, he said:

"I, as president of the council, consulted the president of the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway Company, and the president of that railway company informed me that as president of the council I was to mind my own business. Therefore I cannot answer the honourable member's question."1

Translation: There would be no more railway.

Thirsting for revenge, the member for Comox went to digging up dirt on Robert and found an interview Dunsmuir had done in an American newspaper. In it Robert's statements could be interpreted to mean he thought Vancouver Island should have joined the United States instead of Canada. Attempts by the opposition in the legislature to paint this as treason came to naught, but it was embarrassing enough to scuttle any chance Robert had of being knighted by Queen Victoria.

Worse was to come. A massive explosion at Dunsmuir's Wellington No. 5 shaft in January 1888 killed 60 men. This explosion came just months after another explosion at a VCML mine in Nanaimo that killed 148 men and brought mine safety under deep scrutiny.1 Both explosions were widely (and wrongly) blamed on Chinese miners who couldn't read English safety instructions.

Since Dunsmuir was the largest employer of Chinese miners and also opposed to new laws banning Chinese miners from working underground, he came under a storm of criticism. One white miner said "He has nearly as much power in Victoria as the Czar in Russia. While he is erecting buildings, bridges and railways in Victoria, he is making widows and orphans in Wellington."2

Though he was only 64, in 1889 he began to have premonitions of his own death. He visited a medium (a kind of fortune teller who can communicate with the dead) who told him he would die in April. On April 10 he was found unconscious in his bed at Fairview. When he was awoken he was plainly very ill and he asked doctors if he was in danger of dying.

Robert had prepared two wills, one which left all his business empire and his vast $15 million estate to his wife, and a new one--which he had not signed--that split it amongst his sons James and Alex. The doctors told him he was not in danger of dying and he put off signing the new will. The next day he lapsed into a coma and died. His final act (or rather failure to act) laid the seeds of years of bitter family feuding and the ultimate dissolution of the Dunsmuir empire.

A massive funeral was held in Victoria and all his miners in Nanaimo were given free fare to ride his railway to see it. Thousands turned out to witness a procession that took half an hour to pass by. In eulogies the richest and most controversial man in the province was variously described as a "a hard-boiled Scotchman," "the most approachable of men," and "a grim old pioneer of industry."4

12. The Dunsmuir Legacy

1890s

A view down Bastion Street shortly after Robert's death; a view of a city the coal magnate had been so crucial in building. Robert died the province's richest man, and perhaps its most successful businessman ever. He is also remembered as "the most controversial" man in British Columbia's history.

Though his widow Joan would get the castle she had been promised all those years ago, she would spend years fighting over Robert's estate with her two sons. The business empire quickly fragmented and was sold off piece by piece. The next generation, Robert's grandchildren were "more adept at spending money than making it and squandered the fortune on Paris fashions and Monte Carlo games of chance.”1 By James Dunsmuir's death in 1920 the fortune was all but gone.

* * *

They ruthlessly slashed costs. They vigorously (and successfully) fought off the formation of unions in their collieries. And they saved money by cutting corners on safety wherever possible. The Dunsmuir mines were a major reason British Columbia's mines were then some of the most dangerous in the world. In those days 23 miners died for every million tonnes of BC coal mined, compared to the North American average of six.3

Yet they were all the time distracted in an increasingly bitter fight for financial control with their mother, whom Robert had left everything to in his will. Joan sought to secure the legacy of her eight daughters and fought her sons for every penny, as well as spending an astonishing $500,000 to finally complete Craigdarroch Castle in Victoria.4

Protracted legal battles over the estate drained the family's energy and coffers. Alex, who had become a heavy drinker in San Francisco years before, fell into a depressive alcoholic spiral that ultimately resulted in his early death in 1900. As for Joan she would live on in her castle until 1908.

James entered politics in 1898 and was elected to the legislature. He became premier two years later, though the job bored him and he resigned shortly after, preferring to engage in the high society life his position afforded him. It was fitting then that he became lieutenant-governor in 1906, revelling in entertaining guests at Cary Castle in Victoria.

He also began to sell off the empire his father had built. The E&N Railway went to the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1905, and finally in 1910 all of the Dunsmuir coal operations went to the Canadian Northern Railway. He then retired to a mansion at Hatley Park. The Dictionary of Canadian Biography writes:

"It is difficult to understand why, at age 61, [James] Dunsmuir retired from the corporate world. Perhaps he was wearying of confrontation with increasingly militant workers, or perhaps he was discouraged by the growing popularity of oil in the United States, which was already seriously depleting the firm’s key market. More probably, he sold up at the most opportune time to maximize his profit. He may also have been responding to the increasing value placed on leisure and to the general economic decline of Vancouver Island, or, like his father who withdrew from active corporate participation at the same age, he may simply have lost interest in furthering the empire. Perhaps several of these factors were at work."5

When he died in 1920 the Dunsmuir empire died with him. His several children had no interest in business or politics. They preferred the indulgences of alcohol, parties and luxury that came with being grandchildren of the province's richest man.

As for that empire's creator, Robert Dunsmuir, he left behind a bitterly contested legacy. A complex man, he was celebrated by the business class for his rags to riches gumption, and hated by the working class as a greedy and ruthless robber baron.

The historian Terry Reksten described him:

"He was not a mean-spirited or grasping man. In fact, some found him to be genial, kind-hearted, and generous. But he had no sense of proportion. He did not stop to think that… there was rising on his hill above the city a house [Craigdarroch Castle] that was a symbol of uncounted wealth, of profit and power rather than perseverance and pluck."6

The Canadian Dictionary of Biography summed up his legacy another way:

"Robert Dunsmuir was and has remained the most controversial person in the province’s history. He has been recognized by most historians as a great builder, a pioneer industrialist intent upon shaping his province as much as increasing his personal fortune. He has, on the other hand, been more recently presented, by writers probing the province’s early industrial activities, as British Columbia’s chief symbol of unbridled capitalism, and a ruthless exploiter of men and material. The most recent research reveals that neither view is fully accurate, and suggests strongly that a full-scale study of his personal and business career and the social context in which he lived is needed."7

Endnotes

2. Fort Rupert

1. Lynne Bowen, Three Dollar Dreams. (Lantzville: Oolichan Books, 1987), 38.

2. Bowen, Three Dollar Dreams, 44.

3. Bowen, Three Dollar Dreams, 53.

4. Bowen, Three Dollar Dreams, 53.

3. Proving his Worth

1. Lynne Bowen. Robert Dunsmuir: Laird of the Mines. (Montreal: XYZ Publishing, 1999), 41.

4. Mine Superintendent

1. Lynne Bowen. Robert Dunsmuir: Laird of the Mines. (Montreal: XYZ Publishing, 1999), 48.

2. Bowen, Robert Dunsmuir, 52.

5. Robert's Great Discovery

1. Lisa Dillon, "1.2 Historical Demography of Canada, 1608-1921", Canadian History: Post-Confederation. OpentextBC. Online. Accessed August 13, 2017.

2. "Fertility Rate, total - Canada", World Bank. Online. Last updated 2017. Accessed August 10, 2017.

3. Bowen, Robert Dunsmuir, 73.

4. Daniel Gallagher, "Robert Dunsmuir", Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Online. Last updated 2017. Accessed August 10, 2017.

6. Crushing the Unions

1. Bowen, Robert Dunsmuir, 71.

2. Gallagher, "Robert Dunsmuir", Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Online.

3. Bowen, Robert Dunsmuir, 84.

4. Bowen, Robert Dunsmuir, 86.

7. Ardoon

1. Bowen, Robert Dunsmuir, 73.

2. Bowen, Robert Dunsmuir, 55.

8. Entering Politics

1. Gallagher, "Robert Dunsmuir", Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Online.

2. Bowen, Robert Dunsmuir, 109.

3. Bowen, Robert Dunsmuir, 109.

9. Building a Railway

1. Bob Reid. "The Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway and Robert Dunsmuir," The Society of Notaries Public of British Columbia, (Vol. 18, No. 1, Spring 2009.), 70.

10. The Pinnacle of Power

1. Reid, "The Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway and Robert Dunsmuir", 70.

11. Robert's Death

1. Bowen, Robert Dunsmuir, 127.

2. Bowen, Robert Dunsmuir, 134.

3. Reid, "The Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway and Robert Dunsmuir." 71.

4. Bowen, Robert Dunsmuir, 141.

12. The Dunsmuir Legacy

1. Reid, "The Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway and Robert Dunsmuir." 70.

2. Reid, "The Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway and Robert Dunsmuir." 71.

3. Ross McCormack. Reformers, Rebels and Revolutionaries: The Western Canadian Radical Movement 1899-1919. (University of Toronto, 1977), 9.

4. M. Segger & D. Franklin, Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture, (Victoria: Heritage Architectural Guides, 1979), 285.

5. Clarence Karr, "James Dunsmuir." Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Online.

6. Reid, "The Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway and Robert Dunsmuir." 71.

7. Gallagher, "Robert Dunsmuir". Online.

Bibliography

Bowen, Lynne. Robert Dunsmuir: Laird of the Mines. Montreal: XYZ Publishing, 1999.

Bowen, Lynne. Three Dollar Dreams.Lantzville: Oolichan Books, 1987.

Dillon, Lisa. "1.2 Historical Demography of Canada, 1608-1921", Canadian History: Post-Confederation. OpentextBC. Online. Accessed August 13, 2017.

"Fertility Rate, Total - Canada," World Bank. Online. Last updated 2017. Accessed August 13, 2017.

Gallagher, Daniel. "Robert Dunsmuir", Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Online. Last updated 2017. Accessed August 10, 2017.

Karr, Clarence. "James Dunsmuir." Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Online. Last updated 2017. Accessed August 19, 2017.

McCormack, A. Ross. Reformers, Rebels and Revolutionaries: The Western Canadian Radical Movement 1899-1919. University of Toronto, 1977.

Reid, Bob. "The Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway and Robert Dunsmuir," The Society of Notaries Public of British Columbia, Vol. 18, No. 1, Spring 2009. 63-71.

Segger, M. & Franklin, D. Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture, Victoria: Heritage Architectural Guides, 1979.