Walking Tour

First Bastion of the Foothills

The NWMP in Canada's Wild West

Alexa Dagan

Fort Museum Archives FMP 81.86

If you were to flip open an atlas and compare a map depicting the vast Canadian landscape in the year 1873 to a similar map printed today, you would notice some significant differences. Between British Columbia in the west and Ontario and Quebec in the east, there were no provinces: Just a vast ocean of grassland punctuated by nomadic groups of the Prairie First Nations, that was marked as the North-West Territories. You may look at this great space in between and wonder at the grandeur and mystery of the natural landscape. But in the early 1870s, officials in Ottawa had more pressing concerns: the massive potential the North-West Territories held for agriculture, industry, and most of all, capital.

To develop this land, it would first have to be settled. To facilitate the process, the federal government created a multipurpose force that was both police and military, diplomat and enforcer, and, to the Blackfoot Confederacy of the prairies, both friend and foe. This force, which would eventually become the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and one of the most well known emblems of Canada, marched into the west, facing hardship and adversity to bring law and order to the prairies, and prepare the land for settlement.

On this tour we will explore the role of the North-West Mounted Police in settling the prairies and establishing the community of Fort Macleod. The tour will take you through the old NWMP barracks, once a dense cluster of bunkhouses and stables, but where now only a few scattered buildings remain.

This project is a partnership with the Cultural Heritage Tourism Alliance and Tourism Fort Macleod.

1. Firewater

Fort Museum Archives FMP 87.25.43

1938

This photo from 1920 shows the RCMP returning from a winter ride to enter the main gate of the fort. The temperature was -40 degrees Celsuis. Severe low temperatures in the winter were but one of the challenges the Mounties encountered on the prairies. Four years after this photo was taken, a record low of -45 degrees Celsius was recorded in Fort Macleod.

* * *

The scant number of people loyal to the British Crown worried the government. Settlers were pouring into the American West, and a lot of them made no secret of their belief that the North-Western Territory should become part of the United States. Should the more numerous Americans simply move in and declare their loyalty to America, there was little Canada could do to stop it. The Canadians had good reason to be worried: After all, that's exactly the technique that had been used to acquire territories like California and Texas from Mexico.

To make matters worse, the American presence in the North West mostly consisted of a seedier sort of person who had left American territory to avoid the country's ban on liquor sales. They found the north to be fertile ground for an unregulated liquor trade. These Whisky Traders, some of whom were Civil War veterans or outlaws, took advantage of the Hudson's Bay Company declining fur trade, and found they could exchange guns and liquor with the First Nations in return for furs, horses, and other goods.

This high-proof whisky was often cut with ingredients like chili peppers, ginger, ink, chewing tobacco and laudanum. It was exceedingly cheap and highly addictive.

The brew that the traders were distributing, with all of its questionable ingredients, was named Firewater for its burn and potency. This concoction, in combination with conflicts over horse thefts, bad trades, and cultural clashes, wreaked immeasurable damage on plains First Nations communities, especially the Blackfoot Confederacy.1

Ottawa kept an uneasy eye on the situation for years, leading Lieutenant William F. Butler to write:

"The region of Saskatchewan is without law, order or security for life or property; robbery and murder for years have gone unpunished; indian massacres are unchecked even in the close vicinity of the Hudson's Bay Compay's poste, and all civil and legal institutions are entirely unknown."2

But it was one especially bloody incident known as the Cypress Hills massacre, that made Ottawa realize they needed to intervene.

In late spring, a camp of Assiniboine (Known today as the Stoney Sioux or Stoney Nakoda) residing near a whisky fort erupted into violence following a period of bitter relations between the two settlements. Already on edge, the situation worsened when a group of angry wolf hunters arrived at the fort, following a trail of horse thieves that had gone stale.

Unable to recover their horses from the men who had stolen them—who were, in fact, likely not even Assiniboine—the hunters, intoxicated and incensed, went to the Assiniboine camp in search of their property. The discussion boiled over into a shoot-out that claimed dozens of lives. While both sides shot at one another, only one of the traders was killed, and according to eyewitnesses, the hunters fired the first shot. The exact number of Assiniboine deaths is debated. Some historians place it at around 20, but a letter from an unnamed NWMP officer at the time placed it at 100, while Assiniboine elders state the number is significantly higher, around 300. Regardless of the number, all sources agree that neither women or children were spared.3

A few months prior to the massacre, Ottawa had already begun the process of approving the creation of a police force for the west, recognizing that preparing the land for settlement would first require the establishment of law in the area, and peaceful relations with the largest First Nations group of the region, the Blackfoot Confederacy. The horrific events of the Cypress Hills massacre stoked the fires of a sluggish bureaucratic system to intervene in the west. Within weeks of the news reaching Ottawa, the first 150 recruits for the new NWMP arrived in Fort Dufferin, Manitoba, for training. However, despite the efforts of Colonel James F. Macleod and the NWMP to extradite the men responsible for the massacre and bring them to justice, no one was ever prosecuted for the crime.4

2. The Force

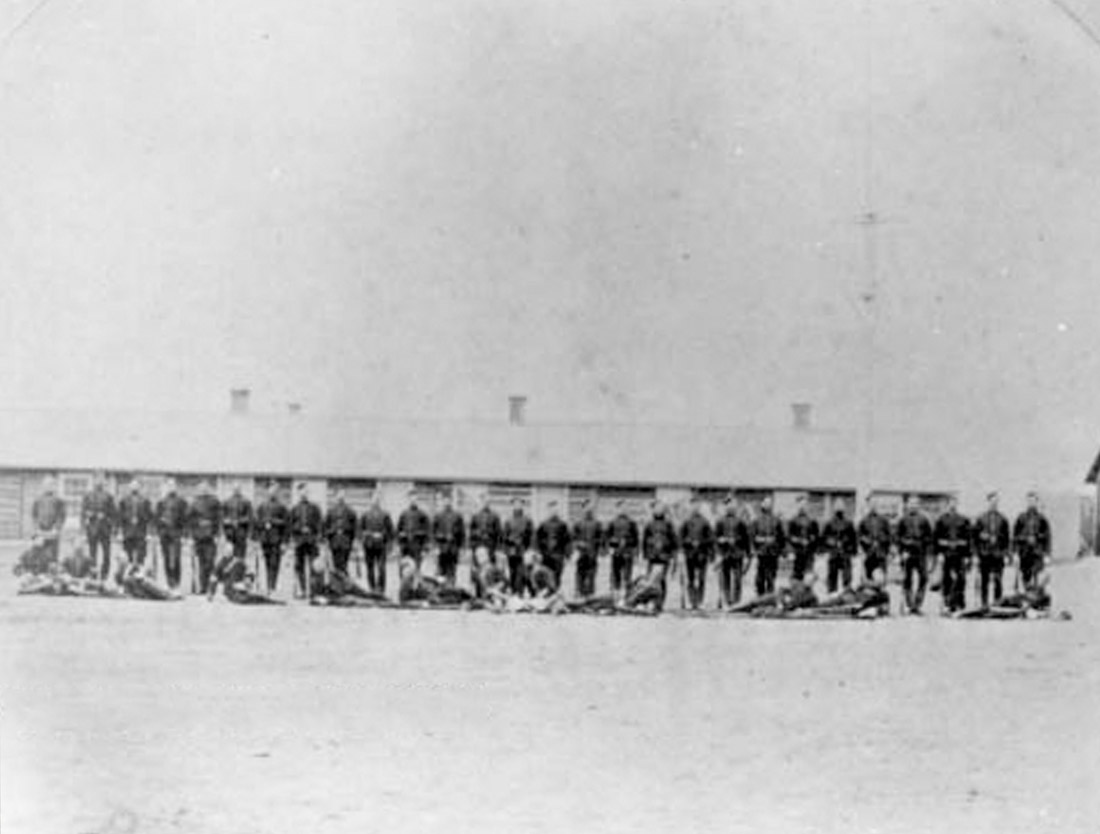

Fort Museum Archives FMP 81.128

1886-1887

This early photo from the mid 1880s shows a line of mounties on parade through a thin layer of snow. The barrack buildings are visible in the background with the men in the foreground, all wearing beavers to keep out the prairie cold. Drills such as these reflected the strong militaristic traditions of the NWMP and were intended to keep the men disciplined, and their skills sharp between patrols and long periods of inactivity.

* * *

Ottawa found inspiration for the unique requirements of a frontier police force from a number of areas. According to historian Greg Marquis, the Irish Constabulary and police forces in British-controlled India, as well as the British cavalry, were all regarded as models for the NWMP, as each dealt with periods of civil unrest in Britain's colonies and handled resistance from the native Irish and Indians. In 1869, Prime Minister Macdonald imagined that the proposed NWMP would have "the military bearing of the Irish Constabulary," while a British army captain, reporting on conditions in Manitoba in 1871, recommended an Irish or Indian style police force. The first commissioner, George Arthur French, had himself served briefly with the Irish Constabulary, before pursuing a military career, while two of his successors both had ties either to the Irish policing system, or had served with the military in India.1

When the NWMP absorbed the more traditionally structured Dominion Police in 1920, an RCMP report summarized the differing nature of the two forces: "The absorption of the Dominion police into the Mounted Police was not free from difficulties. Their organization differed fundamentally. The former was organized and uniformed on the lines of a municipal police force, free to resign on short notice, and its discipline enforced by the civil courts. The latter was organized on military lines, its officers commissioned, clothed in scarlet, disciplined under powers conferred by its own act, and engaged for a fixed term of service, which could not be terminated at will."2

The uniform also merited special consideration. Reports from the west emphasized that prairie First Nations had come to favourably associate the British military uniform with the Queen, who had promised to look after their interests. The NWMP thereby adopted a red tunic and blue pants to mirror this uniform. Upon arrival in Fort Macleod, NWMP Commissioner French drafted a memo stressing the importance of a tidy appearance and professional attitude for the men: "The assistant commissioner directs that the dress and appearance as well as the demeanour of the men of the force should on all occasions and in all situations be such as to create respect for the Corps they belong to. He would like to see the men, if possible, properly dressed when they go beyond the precincts of the fort."3

For recruits, it was not just the lure of adventure that compelled them to sign up, but the promise of land at the end of their term of service. Applicants had to be men between the ages of 18 and 40, with a strong constitution and character, and they needed to be literate in French or English and experienced in the ways of horses. Despite the posting advertising for both English and French, the force was dominated by English speaking protestants.

The pay was poor for what was expected of them, only 75 cents a day for sub constables and $1 for constables (this ranges from $16 to $22 per day in today's money). This rate stayed fixed for several years.4 The men were making the same amount 20 years later, when the average railway labourer was making almost double.5 There was, however, one big perk: 60 acres of land given to each mountie following his three-year term of service.

3. Marching West

Fort Museum Archives FMP 81.86

1894

In this photo snapped in 1894, a group of Blackfoot sit in the grass outside the NWMP fort's barracks. Since the signing of Treaty 7 in 1877, most of the First Nations in the area resided on the Kainai or Piikani reserves nearby, but frequently came into town at Fort Macleod to conduct their business and purchase supplies. On days when treaty payments were made to the nearby reserves, the town took on a festive atmosphere as people flowed into it to make purchases.

* * *

The procession consisted of 275 men, almost 500 animals, including horses, a three-month supply of provisions packed in red river carts and wagons, and two canons weighing a modest ton each.1 As arduous as they expected the march to be, it exceeded the worst fears of all involved. The clouds of biting insects and lack of firewood were a constant annoyance, and much of their equipment quickly proved to be inadequate to face the prairie climate. The tents blew down in the high winds and the pillbox hats issued with the men's uniforms were of little use. The hot, dry weather made water scarce, forcing men, horses, and livestock to drink from the same dirty, shallow sloughs. Drinking unclean water wrecked a gastrointestinal calamity among both men and animals, slowing the march and weakening a large portion of the recruits, while many of the horses perished.

One recruit, James Finlayson, made his first grim entry in his diary on the first day of the march: "Left on the grand march. Struck tents at 4 p.m. Marched two miles and camped. The guard mounted on horse tonight for the first time. Considerable difficulty was experienced before starting by way of balky horses in the hands of inexperienced drivers. Quite a number of runaways among horses and oxen. Many men were thrown from their saddles but none were injured. 15 men deserted last night."2

Finlayson also mentions a plague of grasshoppers that had stripped the prairies of vegetation in advance of the force's path. While the grasslands of the prairies should have made feeding the livestock a non-issue, the insects had stripped the prairies and left little for the horses and cattle. Depleted by hardship, the force split. The weakened men and animals went north to Fort Edmonton to recover, while Commissioner French and Assistant Commissioner James F. Macleod led the remainder of the strong and healthy men to the notorious Fort Whoop-up.

As part of Colonel Macleod's contingent, Finlayson was in good health himself, but reported on the sorry state of the troops, questioning the leadership of the force. In late September, a couple of weeks before reaching Fort Whoop-up, Finlayson wrote, "Washed my clothes and had to go into my drawers and no shirt until my clothes dried. If the people of Canada were to see us now, with bare feet, not one half clothed, half starved, picking up fragments left by the American troops and hunting buffalo for meat and have to pay for the ammunition used in killing them, I wonder, what would they say of Col. French?"3

Despite their objective to deter American incursion and halt American trade into the territory, the NWMP were deeply reliant on the United States as most of the supplies for this March, and later Fort Macleod, came from Fort Benton. Their first objective along the march was Fort Whoop-up, was one of the earliest, largest, and best known American whisky trading posts in Southern Alberta. However, whatever the men may have expected to encounter upon their arrival in Fort Whoop-up, they were sorely underwhelmed. Having been alerted to the imminent arrival of the police, most of the traders had scattered before the force even arrived. While there would be plenty of liquor traders to arrest in the future, with the Fort Whoop-up situation having resolved itself, the next objective loomed: finding a site to call home.

4. James F. Macleod

Fort Museum Archives FMP 86.39.1

1890

In this photo taken on December 17th, 1890, the Artillery Detachment of the D&H Divisions practiced loading cannons for a training drill at the fort. In the early days of the force, the NWMP had a dizzying array of duties to perform. In addition to capturing whisky traders and cattle rustlers, they also did their own carpentry, painting, tailoring, blacksmithing, freighting, farming, repairs, and, when necessary, performed as firefighters, customs and quarantine officers, jailers, and keepers of the "insane."1 This set of responsibilities did not relieve the men of regular training exercises meant to keep their skills sharp.

* * *

While the young man's studies took up much of his time, he also hunted with his father and brothers at a young age. This pastime, in combination with years spent growing up on a farm, gave him a lifelong passion for the outdoors. There was also one other factor of his childhood that shaped his future career: his family had a close relationship with a local Ojibwa family, giving him early exposure and respect for First Nations peoples and their ways of life.3

James Macleod had little passion for law initially, and volunteered for a local militia throughout his schooling. For ten years, he balanced part-time soldiering with his law career, but eventually, this wasn't enough to satisfy his desire for something more.

In 1873, Macleod accepted a commission as the superintendent and inspector of the newly formed NWMP, a role he took to with enthusiasm, thrilled for the adventure and responsibility. He trained recruits at Fort Dufferin, then helped lead them west. Macleod and his division landed on the banks of the Old Man River on September 11th and were allowed little time to collect themselves before work had to begin on the fort, which would give them a location from which to stage patrols and keep a general eye on the liquor trade.

Their presence in the area did much to quell the trade. In December, one of the head chiefs of the Siksika, Crowfoot (Isapo-Muxika), and one of the head chiefs of the Kainai, Red Crow (Mi’k ai’stoowa), met with Macleod to discuss a path forward. As chiefs, both men were keenly aware of the impact the trade had on their people. Red Crow especially adopted a firm stance against liquor, as he had a personal grievance with the trade—he had accidentally killed his own brother during a fight involving alcohol.4 Macleod's respectful nature, and the effort he had already directed towards fighting the liquor trade, earned him the respect of both chiefs, who agreed to cooperate with him to end the trade. This act of diplomacy set the stage for James Macleod's future relationship with the Blackfoot Confederacy, which was characterized by mutual diplomacy, patience, and respect.

Macleod gave the town and the force more than his name. As commander at Fort Macleod, and as commissioner, he set an example with his reason, level-headedness, and care for the well-being of the Blackfoot. While the Department of Indian Affairs, an institution with a devastating legacy, was increasingly eroding the rights and livelihoods of the Blackfoot, the early days of NWMP presence in the prairies was most often defined by cooperation rather than violence. It was the personality and diplomatic characters of James Macleod and the chiefs Crowfoot and Red Crow that made this possible.

James Macleod served as commissioner for four years before stress and frustration from the extensive travel and Force politics, and poor health compelled him to resign and resume his judicial career.

5. "The worst fort I've ever been to"

Fort Museum Archives FMP 87.25.41

1920

This photo shows the exterior of the No. 3 Barracks in the RCMP fort as it appeared in 1920. By that year, the North West Mounted Police had absorbed the Dominion Police and become the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Those recruits coming from the Dominion had some trouble adjusting to the more militaristic tendencies and structures of the NWMP. The Dominion Police were the federal police force who mostly operated in eastern Canada, enforcing federal laws and performing duties such as policing, defending government buildings, guarding government leaders, and keeping the peace.

* * *

The first buildings in the fort were the very basic ones needed for operations, such as a hospital, stables, living quarters, stores, a kitchen, and a blacksmith. The fort was heated using stone fireplaces, which kept the men from freezing, but living conditions overall were poor. Many journeyed over 1200 km to reach Fort MacLeod and were horrified to learn the circumstances they were expected to live in. In 1876, William Parker wrote home to his father, "This is the worst fort I have been to yet, for comfort. The buildings are miserable, mud floors and mud roofs, so that when it rains there is a devil of a mess."1

The initial construction of the fort was entirely completed by the 150 recruits who had travelled west to Fort Macleod initially, one of whom wrote home about the hardships of the construction, "With everyone engaged, the fort was soon finished. Plastering in low temperatures with clay softened with hot water and put on by hand was frigid work."2

Following construction, the force settled in for a long, miserable winter. The first season of 1874–75 was plagued by isolation and boredom. The lack of horses prevented much activity, and the men were frustrated that they had not received pay since leaving Manitoba, and that their uniforms were in rags. In March, Macleod and a small party rode through a late winter blizzard to Helena, Montana, to pick up the men’s pay and receive the first instructions from Ottawa since the departure of French in the fall.3

Colonel Steele reported in his diaries that he had lined the walls of his living quarters with factory cotton to help keep out the dust, contain heat, and tidy up the space in general. It wasn't just the rank and file of the men who suffered from the poor conditions either; James Macleod's quarters in the commissioner's hut weren't much better. In the summer of 1877, a trickle of water ran across the floor during a rainstorm. Macleod thought that it was following an old buffalo track, and he commented wryly, "We may be the only family in Canada that has one."3

As dreadful as the winters were, the legendary prairie Chinook winds brought warm weather that stunned the men and provided them with temporary relief. Chinooks occur when warm winds from the Pacific Ocean descend down the slopes of the mountains, rapidly warming the prairies. Parker, who had complained of the poor fort initially, commented, "The country is looking beautiful, in fact, it is a second Emerald Isle, it is so green. The Prairies are a mass of flowers that smell delicious when I take my evening walk. The bush here is full of wild gooseberries and strawberries."4

Over the years, the living conditions at the fort gradually improved, first with plank floors and roofs that were installed in 1876 following the establishment of the area's first sawmill. The fort remained on this site for 10 years before moving just west of the townsite due to the yearly floodwaters that made the site practically inaccessible.

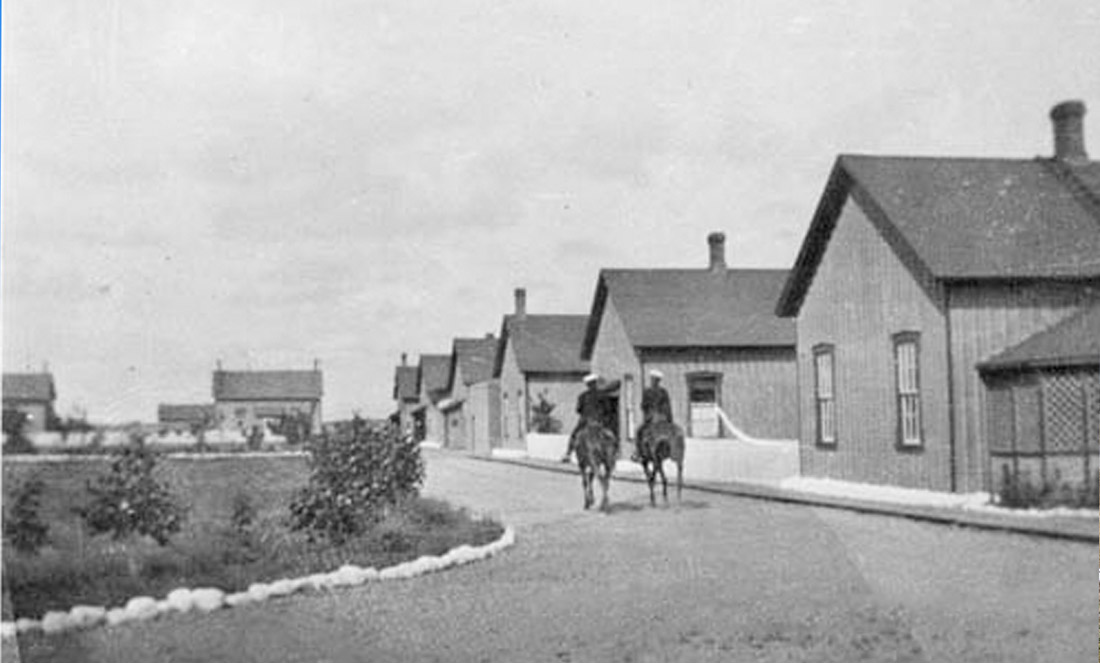

6. The Horse Experts

ca. 1910s

This photo shows a line of barrack buildings, where the men of the force slept. This fort, like others across the prairies, used stoves that burned wood or coal, and lit oil lamps and candles for light, all of which caused a smokey and oily atmosphere inside the barracks. The constables slept on straw-filled mattresses, which meant lice and bedbugs were a persistent problem. In the early 1880s, conditions were poor enough to merit the constables at Fort Macleod issuing a manifesto to their officers demanding improvements to their living conditions.1

* * *

Starting as a staff constable due to his talent with horses, he was soon assigned one of the toughest jobs at the garrison: breaking in prairie horses in frigid Manitoba weather. When the force's great march split so that one half could rest, Macleod went on to Fort Whoop-up, while Steele went with the other half to Edmonton, where he was praised for his work: "sergeant-major Steele has been undeviating in his efforts to assist me, and he has also done the manual labour of at least two men."1

In the years that followed, Steele took part in many of the pivotal events of the prairies. He stands in the famous Last Spike photo, an honour he received for trying to keep liquor and violence out of BC Canadian Pacific Railway construction camps. He played a role in organizing Treaty 6 and 7 negotiations, and is one of the men who tried to persuade Chief Sitting Bull and the Lakota to return to the United States after they fled north as refugees. He also took part in suppressing Louis Riel's rebellion, commanding the mounted troops in the Alberta Field Force and a scout team composed of 65 ranchers and cowboys, as well as 25 NWMP.

For his efforts, he rose through the ranks, becoming superintendent following his command in the Metis rebellion. He eventually took over command at Fort Macleod in 1889, where he met his future wife, with whom he fell very deeply in love. Marie-Elizabeth de Lotbiniere-Harwood was a selective and decisive woman, who had already turned down a couple of proposals before she met Steele. On their first "date", the two went riding together under the guise of Steele teaching Lotbiniere-Harwood how to ride. In a humorous twist, it was Steele who was thrown from his horse, and Lotbiniere-Harwood who rushed to his aid, an event which broke the ice between them. In a later letter Steele writes, "I do not think that the fall I got when we took our first ride has done me any harm. I would not have missed that fall for a great deal as I am sure it made us better acquainted did it not?"2

Due to his rank and marital status, Steele was given a two-storey house between the officer's mess and another officer's house that faced onto the parade square. The couple enjoyed elite community status, and had a good relationship with ranchers in the area.

After almost 10 years in Fort Macleod, Steele was moved to another posting, bringing order to the Yukon in the wake of prospectors striking gold in the Klondike. Two years later, he shipped off to Africa as part of Baron Strathcona's private militia for service in the Boer War. For his service to Canada, and in the Boer War, Steele was knighted on January 1st, 1918. After a long and exciting life, he passed away shortly after the ceremony, following a long struggle with diabetes.

7. Liquor and Vice

ca. 1901 - 1905

In this photo, taken between 1901 and 1905, Superintendent P.C.H. Primrose and Inspector Cortlandt Starnes ride together outside the barracks that contained the officer's mess. By this time, the fort had upgraded from its rustic frontier log cabins to wood frame houses, and had lined its roads neatly with white rocks.

* * *

Sam Steele was put in command of CPR camps to deal with issues relating to liquor, violence, prostitution and gambling as they arose. This was even more challenging in BC, where liquor was not prohibited. To combat this, Ottawa passed a law called the Public Works Peace Preservation Act, outlawing liquor in a strip 10 miles wide on either side of the CPR right of way. Steele, however, was savvy to the wiles of liquor traders by this point and convinced the government to widen it to 20 miles.

Steele took every opportunity to destroy confiscated alcohol, as the force lacked secure storage and the liquor inevitably ended up back on the market. While the CPR workers had no qualms about drinking, members of the force faced an ethical dilemma between enjoying a drink after a long day and staying true to their obligation to stomp out the whisky trade. Occasionally, confiscated alcohol was not destroyed but kept by the men, and officers were forced to take disciplinary action.

Steele spoke about the trouble of punishing members of the force, as well as the general public, for drinking: "We had the detestable, prohibitory law to enforce, an insult to free people. Our powers were so great, in fact outrageous, that no self-respecting member of the corps, unless directly ordered, cared to exert them to full extent. We were expected, on slightest ground of suspicion, to enter any habitation without a warrant, at any hour day or night, and search for intoxicants; no privacy was respected."1

Steele himself was known to enjoy fine whisky and cigars, and occasionally fell into periods of hard drinking. Author T. Morris Longstreth published a book called The Silent Force: Scenes from the Life of the Mounted Police of Canada, in which he states, "Steele's ability to drink was the height of regimental envy; a quart bottle was the measure of his nightcap; yet, however inapposite an ideal such a figure might present on the Sabbath-school platform, to the men in the ranks the sight was more instructive, more inspiring than even texts from Moses or Isaiah." The passage was removed from the book after a lawsuit from Steele's family, who claimed he wasn't a drinker. However, other accounts suggest that while Longstreth's passage may have exaggerated his consumption abilities, he did enjoy liquor.2 Whatever the extent of Steele's indulgence, he had enough control over his drinking that it never tarnished his reputation, nor led him into scandal.

8. The Unpaid Mountie

Fort Museum Archives FMP 81.126

ca. 1910s

This print, taken between 1901-1905, depicts the officer's quarters which ran down the right side of the road in the barracks. These houses are updated versions of the house Sam and Marie Steele would have lived in about 15 years previously. The women who married Mounties not only took on the traditional duties of motherhood and keeping the household, but often assisted the men with their work, taking on the moniker, "The Unpaid Mountie."

* * *

It is well recorded that First Nations and Metis women accompanied men to dances, a practice that became increasingly frowned upon as more settlers moved into the area. The Banker and the Blackfoot, as well as a paper by historian Sarah Carter, report in particular on the attitude of one settler woman, Mary E. Inderwick, who, writing a letter to family back home from her ranch near Pincher Creek, complained about the presence of "Squaw," and "half-breed" women at the dances, and expressed her desire that these women, and their people, remain "isolated in the mountains."1 While the use of these derogatory terms is completely unacceptable today, in Inderwick's time they were offensive, but widespread. While her ideas were indicative of the prevailing attitude at the time, not every settler in the prairies accepted that brand of prejudice. A Methodist missionary upbraided a fellow missionary for his use of the word "Squaw", saying, "In the name of decency and civilization and Christianity, why call one person a woman, and another a squaw?"2

Inderwick, not counting the potential companionship of Metis and First Nations women, also lamented the shortage of settler women nearby.3 Not all NWMP were allowed to marry; this privilege was only allowed to officers, and was discouraged even among them as well as the rank and file, since a man with a wife was not as free to be sent to poorly settled backwaters. According to some, wives were a "mill stone around their [mountie's] necks defeating the efforts to police the North West Territories."4

Once the fort was established, some of the officer's brought their wives to the settlement. Mary Macleod, wife of commissioner James Macleod, was one of the first settler women in Fort Macleod when she arrived in the summer of 1877. She made her home in the cabin that had been the officer's mess. Unlike many of the women who came west with the purpose of marrying, she was born in Manitoba and came to Fort Macleod prepared for the hardships faced by the environment. She and the other women, when they began to arrive, were the primary force behind entertainment in the small community. They organized dances and concerts, and formed clubs. Without their influence, the culture of Fort Macleod would have likely remained rooted in fort activities for some time.

In isolated communities, the officer's wives were a strong source of support. They took on paperwork, prepared meals for prisoners, and opened their own homes for visitors on business, providing them with meals and frontier hospitality.

Civilian women also had roles in NWMP forts as nurses, cooks, teachers, and cleaners. In later years, they worked answering telephones and performing clerical work, as well as taking care of female convicts. In the early 1900s, the Royal North West Mounted Police in more urban areas hired women as fingerprint and lab technicians. In 1946, Dr. Frances McGill was appointed as the force's first honorary surgeon.

Frontier women were accustomed to roughing it. Sam Steele's wife Marie, and often their children, accompanied Steele on inspection tours across the district. While they often stayed with friends or ranchers in the area, they also camped. Marie, like Mary Macleod, also took on the role of organizing concerts and social events that involved both townspeople and police.

While mountie wives like Mary Macleod and Marie Steele enjoyed elite status in their community due to their husbands' high rank, and their own role as organizers, they could be vulnerable as well. When Sam relocated to his new post in the Yukon, Marie was left behind in Fort Macleod with their three children. In his absence, the fort became less welcoming for Marie, who continued to occupy their house in the fort. She wrote to Sam in a panic shortly after his arrival in the Yukon that the replacement commanding officer at Fort Macleod had informed her that since Sam was no longer living at the fort, she was no longer entitled to rations. Sam wrote to the commissioner and Minister Sifton demanding the return of the rations, and reminding them of Marie's Liberal party connections, whom she had enlisted for support. The rations were promptly restored, but the incident highlights how quickly a woman's security could evaporate.5

The role of a mountie's wife was important to the daily operation of the fort and the community. Despite her tireless work, she is also rarely recognized in the historical record. The life of a mountie wife could be incredibly difficult. Not only was it often lonely on the frontier with few other women around for company, but mountie husbands were often sent on far away postings for extended periods of time. Women were often left behind with a household and several children to look after. As the town grew up around Fort Macleod, more pioneer women moved into the area, giving a sense of community to the wives of senior officers.

9. Treaty 7

Fort Museum Archives FMP 80.368

ca. 1910s

This photo from an unknown date shows some mounties on parade at the barracks. Each man holds an unsaddled horse at his side while sitting upon his own mount. The NWMP chose horses not based on their breeding, but on their hardiness and endurance. The horses selected were often smaller animals who were able to ride on long patrols and tolerate periods of low water or grazing. When the need for mounts was particularly high, the mounties would purchase ponies or broncos from the First Nations, whose animals were uniquely suited to the work of the NWMP.

* * *

In the words of the lieutenant-governor of Manitoba and the North West Territories, "If we expect our relations with the [First Nations] to be of the kind which is desirable to maintain we must fulfill our obligations with scrupulous fidelity."2

The negotiations were first set to take place in Fort Macleod, but Chief Crowfoot disliked the idea of meeting the government representatives on their own territory, and moved the meeting to Blackfoot Crossing instead. The Siksika (Blackfoot), Kainai, Piikani, Stoney-Nakoda, and Tsuut'ina all came to the negotiations, although some were late as a protest against the movement to Blackfoot Crossing, which was further away from their own territories. Lieutenant-governor David Laird and Commissioner James Macleod led their side of the negotiations, while Chief Crowfoot led the other and the famous Metis guide Jerry Potts was one of the translators. The result of the meeting was Treaty 7, the last of the numbered treaties signed between the government of Canada and the Plains First Nations.

Treaty 7, like the other treaty documents, is today a highly controversial document that ceded roughly 130,000 square kilometres of land in southern Alberta to the Canadian government. While it appears that the leaders of the negotiation entered into it with respect and goodwill, the legacies of the treaty are deeply troubling. The premise is highly debated, with many suggesting that the two sides had different cultural understandings of the purpose of the treaty. The Blackfoot viewed it as primarily a peace treaty that dictated the terms of settlement: they would share their lands in return for several promises from the government of Canada. The government and its representatives, however, thought the treaty negotiated the sale of the land into their ownership.3

Recorded oral histories from Blackfoot Confederation Elders reinforce that treaties were an important part of their culture, but that they had a different connotation than how the settlers intended the numbered treaties, "Our people's concept of the treaties is entirely different from the non-Native's point of view. Treaty, or innaihtsiini, is when two powerful nations come together in peace agreement, both parties coming forward in a peaceful, reconciliatory approach by exercising a sacred oath through the symbolic way of peace, which is smoking a sacred pipe and also through the exchange of gifts to sanction the agreement which can never be broken. The smoking of the pipe is similar to the non-native's swearing on the bible." Elder Louise Crop Eared Wolf continues, "Indian people's concept of treaty is one of creating a good and lasting relationship between two nations who at one time were at war with one another… In signing a treaty with the Queen, they had understood Treaty 7 as a sacred agreement. The basis of the relationship between the blood tribe and the government of Canada had been based on the treaty."4

Peigan elders also recall that there was much anxiety prior to signing that the agreement would cause them to lose their way of life, but the realities of the starvation they faced with the disappearance of the buffalo, and fear of a massacre like those that had occured in the United States compelled them to sign.5

Furthermore, some question the ability of the interpreters. Although Jerry Potts was an incomparable guide and invaluable asset to the NWMP due in part to his conversational fluency in both Blackfoot and English, there is some evidence that he may have struggled with the intricacies of the legal jargon in the treaty, and that the legal terms could not have been easily translated to Blackfoot, as there were few equivalents in their language.6

At the meeting, David Laird made a speech promising to pass laws to protect the buffalo, and to put an end to whisky forts. He added, however, that the buffalo would soon be gone, and that the government wanted the First Nations to switch to agriculture, for which they would be given support. Meanwhile, First Nations leaders wanted assurances that they would be able to continue to hunt and fish on their traditional lands, in addition to annual payments, reserve lands, and education. In the end, every group was to receive lands, and individuals were entitled to an immediate cash payment, which varied according to status. The government also made promises regarding supplies, education, and cattle.

While both parties agreed to these terms, in the words of author J. Edward Chamberlin, "Canada did not keep its word."7 Cree and Metis continued to trespass, the buffalo disappeared, and settlers continued to move in. Support for agricultural transition was not given, and in cases when it was, the land was frequently unsuitable.

Despite these issues, Treaty 7 is considered one of the most well-negotiated treaties in Canada, and the Blackfoot Confederacy negotiated with such skill that they retain some of the largest reserve lands in Canada. Additionally, the work of the NWMP and James Macleod settled the west with little overt violence when compared to the bloody conquest of the American west, or even some areas of eastern Canada. However, the Blackfoot suffered indescribably in the years that followed the treaty. They starved from the insufficient government rations, while sickness and childhood illness ravaged the reserves, the lands given to them as reserve sites were often unsuitable for agriculture, and the buffalo were all but gone.

Father Lacombe, who had encouraged the Blackfoot to sign the treaty, wrote in a letter to David Laird describing their poverty after signing, "I have never seen them so depressed as they are now; I have never seen them before in want of food… they have suffered fearfully from hunger."8

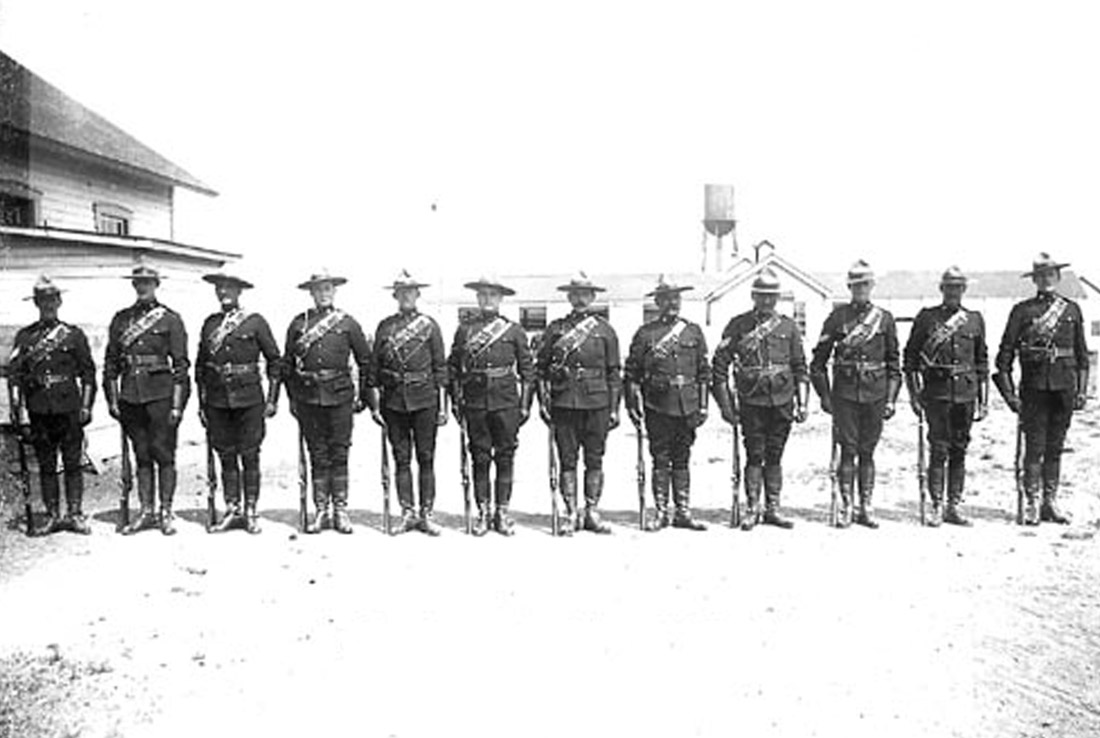

10. Isapo-Muxika

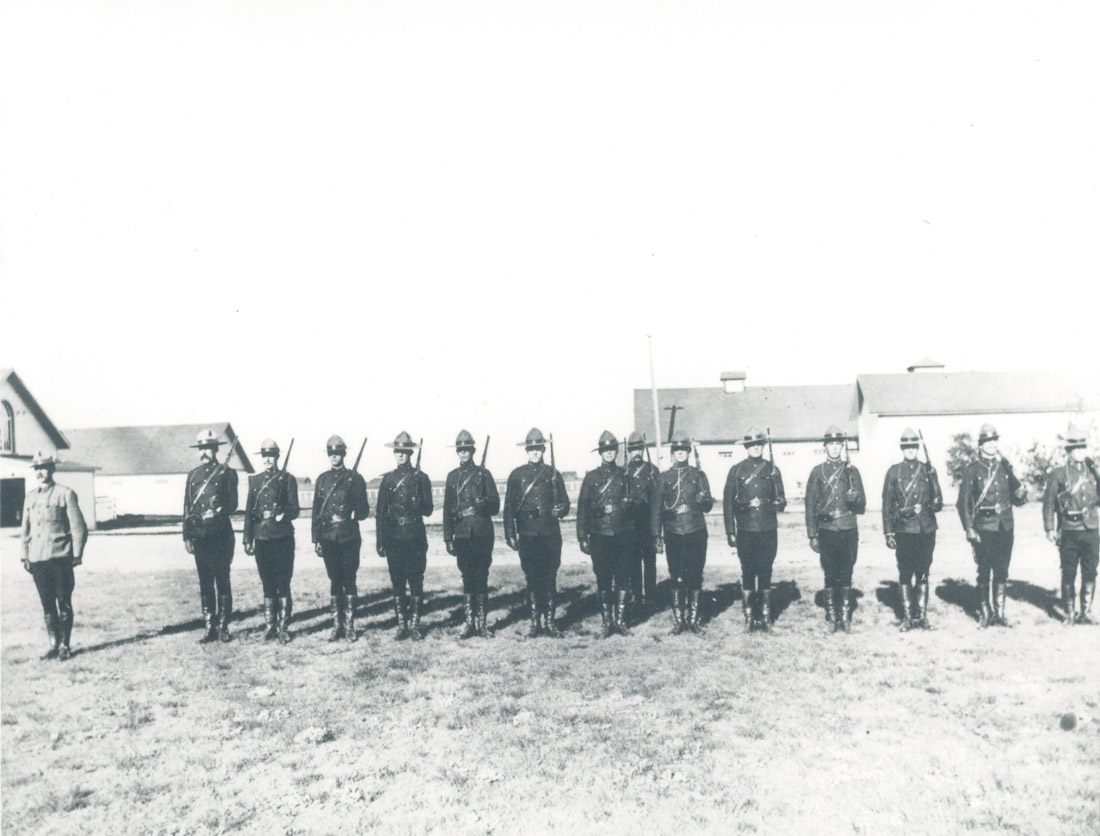

1901 - 1920

This photo shows a group of Royal North-West Mounted Police standing in a line for a picture. Prior to 1901, pillbox hats or military style helmets were the official headgear for the NWMP uniform. They were accompanied by a simple red Norfolk jacket and steel-grey Bedford cord breeches. Men wore different styles of uniform depending on what they were doing and what season it was; in winter, the official uniform was often inadequate for the conditions. The Stetson hat was only adopted at the turn of the century, although men had been wearing it unofficially for years due to its superiority over the issued headgear.

* * *

As he grew, he proved himself to be a respected and capable warrior, and demonstrated strong leadership during raids. When the chief of his band died in 1865, Crowfoot became a minor chief of the Siksika and proved himself a wise, practical, and diplomatic leader. As someone who was inclined towards peace, he cautioned restraint when dealing with enemy tribes, although he was no coward and was not opposed to war when it was necessary. As a minor chief, Crowfoot tried to establish friendly relations with the fur traders and missionaries that had begun to arrive in the area. During this time, he became one of the Siksika's three head chiefs after a smallpox epidemic claimed the lives of several Blackfoot leaders.

Crowfoot first met James Macleod in December of 1874, and the two soon established a friendship. The co-operative efforts of these men played a large role in shaping the attitudes of their people, and maintaining peace in southern Alberta. While Crowfoot was one of the head chiefs of the Siksika, the Kainai and Piikani each had their own leadership. Nonetheless, Crowfoot was put into the position of speaking on behalf of the Blackfoot during the Treaty 7 negotiations due to his leadership and diplomatic skills as well as his close relationship with both Father Lacombe and Commissioner Macleod. In his famous speech upon signing the treaty, Crowfoot expressed his gratitude to the NWMP for their help in ending the liquor trade with the words, "if the police had not come to this country, where would we all be now? Bad men and whiskey were killing us so fast that very few of us would have been alive today. The Mounted Police have protected us as the feathers of the bird protect it from the frosts of winter. I wish them all good, and I trust that all our hearts will increase in goodness from this time forward."2

By 1881, the NWMP were no longer responsible for mediating between the Blackfoot and the Canadian government, and the newly established Department of Indian Affairs was to handle their affairs. The next several years eroded Crowfoot's trust in the government and the NWMP, who enforced the government's policies. When Louis Riel began spreading word of his rebellion, he sent messengers to Crowfoot to ask him to join their fight. While Crowfoot eventually opted out of participating, he did not refuse the Metis immediately. Instead, he wisely waited several days, receiving both government officials and rebel messengers to hear their cases. Only after he ascertained that the Kainai and Piikani would not be supporting the rebellion did he firm his stance on the side of the government. His standing with the Canadian government made him nationally famous. He was praised by the government for his loyalty, although his decision was likely based more on the belief that the Metis were fighting a losing battle, rather than on steadfast loyalty to the government.3

Chief Crowfoot died in 1890 after years of watching his people starve and struggle, and becoming increasingly pessimistic about the government and his people's future. He saw only four of his children live to reach maturity, as the others were claimed by tuberculosis. His adopted son, Poundmaker, was sent to prison for supporting the rebellion. After his death, his foster brother became chief and inherited the problems facing his people. Shortly before Crowfoot's death, he was quoted with the words, "What is life? It is the flash of a firefly in the night. It is the breath of the buffalo in the winter time. It is as the little shadow that runs across the grass and loses itself in the sunset."4

11. The Incomparable Jerry Potts

1879

In this 1879 photo, a long line of police from the C Troop stand in a line for a photograph, while several others lay propped on one arm in front of them. Even with their duties, the men of the force still found time for humour and camaraderie. The majority of the force came from a British or Canadian background, with a minority of French-speaking recruits. Additionally, while Prime Minister MacDonald had originally wanted Metis units with British commanding officers, increasing conflict between the Metis and the Canadian government caused officials to scrap this idea. Yet while First Nations and Metis were not among official original recruits, their contributions to the NWMP as guides and scouts were invaluable.

* * *

The force hired many guides and scouts in the early years, but there are perhaps none so well known as Jerry Potts. Born to a Kainai mother and a settler father who died shortly after his birth, Potts was raised between his mother's people and the world of an American fur trader who adopted him at Fort Benton when he was around five years old. Throughout his early life he learned the languages and cultures of both peoples, as well as becoming acquainted with various other First Nations who visited Fort Benton. When he reached adulthood, Potts worked for the American Fur Company, then later became a hunter and guide for various whisky traders who were entering the territory. During this time, he also gained recognition as a warrior as he fought battles alongside the Blackfoot against the Sioux, Crow, and Plains Cree.1

By the time he reached his early 30s, Potts was a man who had spent his entire life deeply steeped in the world of the frontier, and he was well-known around Fort Benton for his linguistic, geographical, and cultural knowledge. When Commissioner French visited Fort Benton in 1874 to purchase supplies and fresh horses for the weakened recruits marching west, he met Potts. Quickly recognizing the value of the man's skills, he hired him as a guide, interpreter, and scout. Potts led the men first to Fort Whoop-up, then onward to a site he recommended for their fort: the island in the Old Man River.

Potts was known not only for his skills, but for his easy-going, straightforward matter. The Banker and the Blackfoot records an interaction that showcases Potts' direct and sardonic mannerisms, as he led a scouting mission for a party that included the Marquess of Lorne, who was the governor-general of Canada at the time and impatient to reach their destination.

"What's over the next hill?" No reply. So he asked again, "what's over the next hill?" Still no reply from the taciturn Potts. Finally, the marquess repeated his question with all the imperial authority he could muster. "Now say there, my man, what's over the next hill?" "Another hill," replied Jerry and returned to his musings.2

In his 22-year-long career as a guide with the NWMP, Potts led most of the force's major patrols, trained other guides, and helped maintain good relationships between the force and the Blackfoot. He organized the first meeting between Colonel Macleod and Chiefs Red Crow and Crowfoot, and in his role as interpreter, helped facilitate the friendship that grew between the three men. In addition to all of the other discussions he interpreted during his career, he translated for one of the most important negotiations that would take place in the territory, Treaty 7.

After years as an invaluable resource and friend to the NWMP and the community of Fort Macleod, Potts passed away in 1896 after years of struggling with tuberculosis. In his obituary, the Fort Macleod Gazette and the Alberta Livestock Record celebrated the life of the man who “made it possible for a small and utterly insufficient force to occupy and gradually dominate what might so easily, under other circumstances, have been a hostile and difficult country. . . . Had he been other than he was . . . it is not too much to say that the history of the North West would have been vastly different to what it is.”3

12. Strike

Fort Museum Archives FMP 80.171

1912

In this photo taken at the barracks in 1910, a group of mounties stand in line at full attention. In 1904, King Edward VII officially added "Royal" to their title, turning the force's name into the Royal North-West Mounted Police. In 1920, the name changed again to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police after the RNWMP absorbed the Dominion Police.

* * *

The NWMP also broke labour strikes on behalf of the CPR. In the late 19th Century and the first couple decades of the 20th, worker's rights and labour unions were virtually unheard of. While some labour unions existed, they lacked the rights and power they have today, which limited their effectiveness. The result was that general and industrial labourers were often overworked, underpaid, and poorly treated. The state prioritized the interests of corporations and capitalist enterprises like the CPR over the well-being and compensation of workers, and used the NWMP to ensure these interests were unimpeded.

In 1883, Sam Steele and a small contingent were sent in to suppress two large strikes, one consisting of 130 construction workers at Maple Creek and the other concerning CPR engineers who went on strike following a reduction to their wages. The company did everything they could to force the workers to return to work, including hiring scabs. After the strikers allegedly damaged company property, they called in the NWMP, although the engineers denied responsibility for the damage. The strikers were forced to return to work within a few weeks, on the company 's terms, following the involvement of the NWMP.

The climate of worker dissatisfaction coincided with public scrutiny of the NWMP. Their support of the CPR reflected the desire of the NWMP higher-ups to curry favour with the powerful CPR corporation, the government who supported them, and the press, which was generally supportive of strike-breaking. In 1884, the Regina Leader published an editorial in support of the police: "The Mounted Police have progressed in efficiency, and on several occasions… especially in connection with the late railway strike… have shown how admirably adapted they are to meet the needs of a country in the position of the North-West."1

During the next couple years of construction, the situation for workers did not improve. In April 1885, several hundred construction workers went on strike when the CPR failed to pay them for three months of labour. Colonel Steele and his men soon arrived on the scene and subdued the large crowd. While there may have been the odd individual in the rank and file of the NWMP who may have been sympathetic to the worker's plight, Steele firmly believed in the cause he was enforcing. He recalled the event in his diary, and his attitude towards the strikers was strict: "I assured them that they made a great mistake in striking and that, if they committed any act of violence and were not orderly in the strictest sense of the word, I should inflict on the offenders the severest punishment the law would allow me."2

Even though by today's standards the workers were well within their rights to demand pay, their protest was struck down. While this was a sad chapter in the history of worker's rights, this became a pivotal moment in the force's history, as Steele and a relatively small number of men prevailed against hundreds of strikers. Despite the dispersion of the crowd, however, many continued to strike. While Steele had stated that he intended to prosecute the strikers to the fullest extent of the law, the North West Rebellion was boiling over and there would be no reinforcements if the situation turned violent. Recognizing the tenuous position they were in, he sentenced the ringleaders to either a $100 fine or 6 months in prison, rather than the "severest punishment" he may have had in mind.

Thanks to the efforts of NWMP, the CPR was able to complete their construction in good time with very few concessions or allowances made to their workforce. The workers, however, suffered enormously from illness, poverty, injury, and death. The federal government was so impressed by the efficient work of the NWMP in shutting down the strikes that they established a tradition of sending in the force to break up labour strikes and demonstrations during World War I and the Great Depression. The most notable of these were the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919, and, not far from Fort Macleod, the 1906 Lethbridge miners' strike.

In Lethbridge, near the beginning of the 1906 strike, tensions were so high that the mounties had 34 officers and men on strike duty, as well as 48 mounties on call in nearby Regina and Fort Macleod. This particular strike, however, was effective; by the end of several months of demonstrations, the workers earned a significant pay raise, a grievance procedure, and the right to belong to a union. Furthermore, while there were some shows of force on each side, there were almost no incidents of violence between the two groups.3 In fact, according to a paper by historian William M. Baker, labour demonstrations and strikes across Canada had significantly lower fatality rates than similar events in other nations, and both police and protestors appeared to avoid excessive violence when possible.4

13. Manhunt

Fort Museum Archives FMP 87.25.22

1922

In this photo, a single mountie leans casually between two horses hooked up to a cart at the RCMP barracks. This photo was likely shot between 1906 and 1928. The man in this photo sits in his casual dress, presenting a more relaxed side of the mounted police. Even out of uniform, the iconic Stetson hat remains a core piece of equipment on the prairies.

* * *

By the mid 1890s, there were many older Kainai who remembered life before the arrival of the NWMP and the signing of Treaty 7. They lived according to elaborate spiritual and social laws that were based around generations of tradition and oral history, and that in many cases were deeply rooted to their environment. The signing of Treaty 7 and the arrival of increasing numbers of settlers changed everything. Rather than living in ways dictated by their own traditions, religion, and social rules, they were obliged to obey the laws of the NWMP and the Canadian government, which often conflicted with their own beliefs. While there was necessary cooperation, and even friendships, between the Blackfoot Confederacy, the NWMP, and the settlers, some resentment towards the newcomers for the loss of traditional ways of life and the curbing of freedom still simmered on the reserve.

In the winter of 1895, Si'k-okskitsis, or Charcoal, as interpreters called him, caught one of his wives, Pretty Wolverine Woman, having an affair. The affair was troubling, but the man was also her cousin and the two therefore broke a strict cultural taboo among the Blackfoot. This would have severely damaged Charcoal's honour and status in the community. Charcoal reacted to the insult by shooting the man, Medicine Pipe Stem, through the eye, breaking Canadian law in the process.

In the weeks that followed, Charcoal evaded capture, and, in what appeared to many to be a murderous rampage, shot and injured a farmer, made an attempt on the life of Chief Red Crow, shot at an NWMP officer, and stole several horses, all while narrowly evading the police on many occasions. Steele, in charge of organizing and directing the manhunt, was increasingly frustrated by Charcoal's ability to avoid capture. Although he directed the search with competence, the press published editorials that often veered into wild inaccuracy. The editor of the Macleod Gazette, an ex-policeman himself, sought to explain the difficulty of the task at hand to those reading the eastern press: "Surprise has been expressed that one Indian should have been able to elude all the police and Indians who have been looking for him for a week past… If these persons knew the country, there would be no occasion for surprise. In the first place the fugitive is a very clever Indian, and in the second place, as long as he is able to remain in the brush or timber, it is next to impossible to corner him."1

Even Sam Steele, despite his anger at being repeatedly beaten by Charcoal, had to admit some grudging respect for his skills: "A Blood [Kainai] Indian whose pluck and endurance were a wonderful example of what the greatest of natural soldiers is capable of, when put to the test."2

Regardless, with mounting pressure from both the Kainai and settlers who feared Charcoal's erratic actions, Steele was desperate to capture him before he killed anyone else. To this end, he bent the law. In an act of prudence, but questionable legality, Steele took Charcoal's family, a total of 26 individuals, including children, into custody, and pressed Charcoal's two brothers into a deal. If they aided the police, their families would be freed. Furthermore, the adult members of Charcoal's family had aided him while he was on the run, so arresting them effectively cut off the fugitive's aid. The children could not be separated from their caregivers, so they were taken into custody as well. While Steele used the premise of aiding and abetting Charcoal to excuse his actions, these charges were never formally applied.3

By killing Medicine Pipe Stem, Charcoal understood that he had broken the NWMP's law, and that he would hang for the act. As an individual of spiritual significance in his tribe, he decided to die according to his culture's traditions, rather than those of the settlers. According to historian Hugh A. Dempsey, killing a warrior of high standing would allow them to become a messenger to the afterlife who would detail Charcoal's accomplishments as a warrior and therefore secure him high status in the afterlife.4 Weeks after the hunt began, Charcoal accomplished this goal. On November 10th, 1896, during a chase, Charcoal shot and killed NWMP Sergeant W. B. Wilde.

Shortly afterwards, Charcoal returned to the home of his brothers, unaware of the deal they had struck with Steele. When he entered the dwelling, his brothers captured him and held him until the NWMP arrived. Their families, as well as the son of one of the brothers who had been arrested previously for an unrelated offence, were released as Steele had promised.

The story of Charcoal is one of a clash of cultures and traditions. In the years that followed, while many remained horrified by his actions, some viewed him as a folk hero who had defied the police and followed his own cultural traditions.5 Charcoal, a small, middle-aged man in the late stages of tuberculosis, managed to evade capture and run circles around the mounties for weeks. He stole several prized horses and nearly murdered several people before finally killing a mountie. Sergeant W. B. Wilde was well-liked and mourned by his community, and his loss was a tragic blow to the force.

14. Changing Times

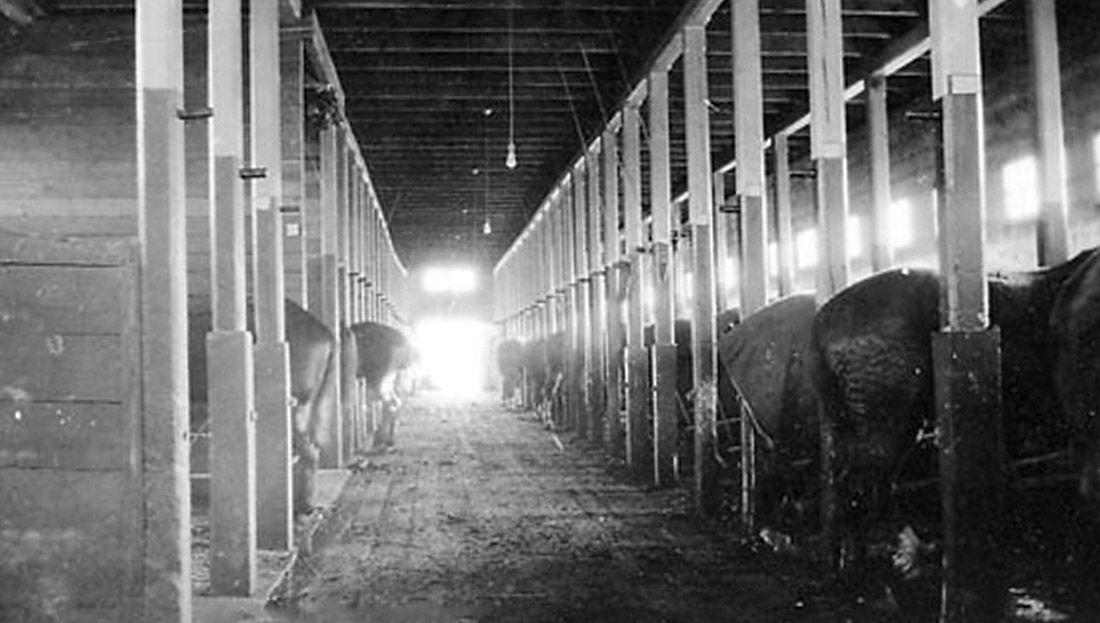

1927

This photo shows long rows of horses in the Number 1 stable at the RCMP post in 1920. By that year, the force had become the RCMP, and despite various threats to their existence in the form of government changes and reservations, had time and again proved their usefulness to the government and the people and eventually cemented their role in Canadian society. As the force changed to accommodate the evolving needs of the country, the Blackfoot struggled to adapt to a world that was changing swiftly around them.

* * *

For the Blackfoot, fresh meat was scarce, so they were often forced to subsist on pemmican, dried meat, and bacon. Worse, the flour they received from the government rations to make pemmican often arrived black, because it had been made from frozen wheat. Measles and scarlet fever ravaged Blackfoot communities, causing high infant mortality. In 1881, 3,560 Kainai were collecting annual treaty money; by 1890, it was down by half, and by 1896, the Kainai numbered only 1,300. Food rations were so slow in arriving that the Blackfoot gave Commissioner Dewdney the name Apinau-kusi, meaning "Tomorrow," due to his frequent and often unfulfilled promises that food would arrive tomorrow.1

Meanwhile, the NWMP were often called upon to resolve disputes around cattle theft. Settler Ted Maunsell lived in a log cabin with his brother on a plot of land where they planned to start a ranch. Due to their own lack of capital, and their hospitality in offering food to a local Kainai family, they soon faced starvation. Finally, they were able to secure a herd of 103 cattle for their ranch and their fortunes turned. Unfortunately, their herd was raided several times over the following weeks, and by the end of the season, their cattle numbered only 59. Frustrated, they met with several other ranchers and took their complaints to Colonel Macleod. Macleod responded to their complaints by saying that if they could identify the men who had killed their cattle, then they could be punished. However, no one could produce an identity.

Macleod added that several settlers were starving as well, and were not above stealing cattle, and that if any settler shot a Blackfoot, they would be hanged. The land was not yet officially open for settlement, so any cattle the settlers brought to it were acquired at their own risk. They could neither protect their property, nor expect compensation for the loss of the animals.2

Maunsell left unsatisfied, but with a touch more sympathy for the plight of the Blackfoot. He even admitted later in life that he and his brother "would have stolen themselves. If they found a place to steal from and something to steal."3

The atmosphere underwent a shift in 1885, following the Northwest Metis Rebellion. The Indian Act instituted the pass system to keep First Nations on reserves and restrict their free movement around the territory by requiring every person leaving the reserve to have a pass issued by the Indian agent. When the system was first implemented, it was intended for bands who were thought to have actively rebelled, or aided the rebellion, but the government tried to make passes universal in 1890. The NWMP actively protested the pass system, on both legal grounds, and on the practicality of enforcement. James Macleod was a justice of the peace at this time, and stood firmly against the system.4

For Indian agents, the pass system could be used and abused to exercise authority. David Laird, the newly appointed Indian Commissioner, wrote a letter reminding the agent on the Kainai reserve of the illegality of the system in the late 1890s: "The pass system as it stands cannot be enforced by law."5

Yet even some of the Indian agents were against the pass system. William Pocklington on the Kainai reserve stated to Sam Steele, "The Indians are not confined to the reserve by any law or regulation… and [they] know they have the right to come and go as they please."6

Not long after the indignities of the pass system, residential schools were established for the Blackfoot. There were two for the Kainai Reserve, St. Paul's and St. Mary's. During the schools' history, 116 children passed away or went missing and never returned home.7 Residential schools separated children from families and removed them from their culture for the purpose of assimilation. The NWMP played a role in the schools as well, with school officials and Indian agents calling on them to return runaways to the schools.

A medical officer who worked with the Blackfoot wrote, "Indians themselves are for the day school, [which] serves as a little social and cultural centre on the reserve and its influence is conveyed by the children from the school to their parents and relatives in the home. My chief objection to the residential schools is the disruptive effect upon the family. The children become estranged from their parents and this factor is a source of grief to the latter. I have had Indians come to me asking for a day school on their reserve who told me with tears in their eyes how their children returning from residential school ridiculed and despised their fathers and mothers..."8

These measures endured. The pass system was enforced into the 1940s, before finally being redacted in the 1950s. The government began to close residential schools across the country in the 1970s, but the last one remained in operation until as late as 1996. The residential school system is one of the most disturbing legacies of the Indian Act, it stripped children from their family, culture, and language and facilitated such horrific abuse on children that First Nations communities across the country are still working to heal the trauma.

15. Conclusion

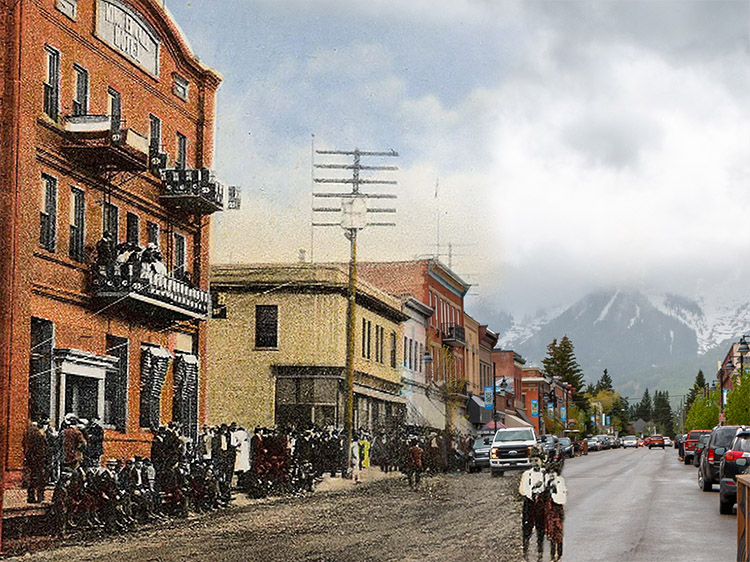

Fort Museum Archives FMP 80.56.4

1924

The back of this photograph reads, “Indian celebration Macleod Alta. July 1st 1924. Indian tepees, canvas and hand decorated", with the addition, “Originally these were of buffalo hides - tepees.” Some Teepees (also spelled Tipi), were decorated with designs that were specific to the owner's band or nation, and often had spiritual symbolism.

* * *

The legacies of these accomplishments, however, are controversial. While the Blackfoot were grateful for the end of the liquor trade, and the seemingly inevitable settlement of the prairies was handled without war or bloodshed, the mounties brought with them the end of the Blackfoot's traditional way of life. The fur trade and the Hudson's Bay Company had already all but guaranteed the end of the buffalo, but the arrival of the NWMP represented the first true wave of settlement to the area. All this occurred despite Treaty 7, a document that could have established the Blackfoot as a self-governing nation equal to that of Canada and protected their way of life. But it didn't.

Meanwhile, the CPR was built, small settlements were connected to urban centres, and communities boomed, but the price was steep. The mounties enforced the shady practices of a corporation that profited enormously from cheap labour, while thousands of workers died from accidents, exhaustion, and sickness. Yet labour protests across the country were characterized by a more peaceful relationship between strikers and the RCMP, with less loss of life, than similar incidents in other countries.

Even the force itself, despite its promise, had a rocky start. The "Great March West" was disastrous, and the men failed to receive pay for their first several months of service, while they lived in appalling conditions. Although things improved over the next several years, life in the force was challenging for the first recruits.

The legacy of the force may be mixed, but without them, the landscape of modern Canada would be drastically different. How might the labour movement have been affected if the mounties had had the option and desire to support the workers rather than the CPR? What would have happened to the Blackfoot if either they, or the NWMP, had decided on war instead of negotiation? What if Louis Riel's North West Rebellion had been successful? The outcome is up for debate, but it is possible to learn from the stories of the past, and hope to do better. Whatever the future holds, it is important to remember the roles not only of Sam Steele and James Macleod, who both did impressive work with a small but dedicated force, but also Mary Macleod and Marie-Elizabeth Steele, who did silent work to support their husbands, Chiefs Red Crow and Crowfoot, who chose peace and negotiation at every turn, and Charcoal and W. B. Wilde, the casualties of a rapidly changing world.

Endnotes

1. Firewater

1. Edward Butts, "North-West Mounted Police," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Dec. 6 2016. Online.

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/north-west-mounted-police

2. Edward Butts, "North-West Mounted Police."

3. Alex Boyd, "How the Cypress Hill Massacre of 1873 - Likely Canada's first mass shooting - helped create the RCMP," The Toronto Star, April 25, 2020. Online.

https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2020/04/25/how-the-cypress-hills-massacre-of-1873-likely-canadas-first-mass-shooting-helped-create-the-rcmp.html

4. Roderick Charles Macleod, "Macleod, James Farquharson" in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003. Online. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macleod_james_farquharson_12E.html

2. The Force

1. Greg Marquis, "The 'Irish Model' and nineteenth-century Canadian Policing," The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 25, No. 2 (1997): 208 - 209. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03086539708582998

2. Edward Butts, "North-West Mounted Police," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Dec. 6 2016. Online.

3. Fort Macleod History Book Committee, Fort Macleod - Our Colourful Past (Fort Macleod: Friesen Printers, 1977), 20.

4. Fort Macleod History Book Committee, Fort Macleod - Our Colourful Past, 21.

5. Jim Selby, "One Step Forward: Alberta Workers 1885 - 1914" in Working People in Alberta: A History, ed. Alvin Finkel (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2012), 44.

3. Marching West

1. Gerry Burnie, "The 'Great March,' 1874" Interesting Canadian History, June 13, 2013. Online.

2. James Finlayson, “Jottings on the March from Fort Garry to Rocky Mountains,” 1874. — Photocopy of handwritten account and typescript; from original in Library and Archives Canada, MG 29, E-58. PDF.

https://glenbow.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/m-9836-83-transcript.pdf

3. Ibid.

4. James F. Macleod

1. Fort Macleod History Book Committee, Fort Macleod - Our Colourful Past, 20.

2. Roderick Charles Macleod, "Macleod, James Farquharson."

3. Roderick Charles Macleod, "Macleod, James Farquharson."

4. Hugh A. Dempsey, "Mi'k ai'stoowa (Red Crow)," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Oct. 20, 2020. Online. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/red-crow

5. "The worst fort I've ever been to"

1. Fort Macleod - Our Colourful Past, 18.

2. Fort Macleod - Our Colourful Past, 17.

3. Fort Macleod - Our Colourful Past, 18.

4. Fort Macleod - Our Colourful Past, 19.

6. The Horse Experts

1. Stanley W. Horrall, The pictorial history of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (Toronto, ON: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1973), 84.

2. Rod Macleod, Sam Steele: A Biography (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2018), 38.

3. Macleod, Sam Steele: A Biography, 117.

7. Liquor and Vice

1. Fort Macleod - Our Colourful Past, 21.

2. Macleod, Sam Steele: A Biography, 92 - 93.

3. Brown, An Unauthorized History of the RCMP, 16.

8. The Unpaid Mountie

1. J. Edward Chamberlin, The Banker and the Blackfoot - A memoir of my grandfather in chinook country" (Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), 25., Sarah Carter, "Categories and terrains of exclusion: constructing the "Indian Woman" the early settlement era in western Canada," Great Plains Quarterly 13, No. 3 (Summer 1993): 147.

2. Sarah Carter, "Categories and terrains of exclusion," 148.

3. Sarah Carter, "Categories and terrains of exclusion," 147.

4. Fort Macleod - Our Colourful Past, 23.

5. Rod Macleod, Sam Steele - A Biography, 147.

9. Treaty 7

1. First Nations Studies Program, "Royal Proclamation, 1763," Indigenous Foundations - University of British Columbia, 2009. Online. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/royal_proclamation_1763/#:~:text=The%20Royal%20Proclamation%20is%20a,what%20is%20now%20North%20America.&text=The%20Proclamation%20forbade%20settlers%20from,then%20sold%20to%20the%20settlers.

2. J. Edward Chamberlin, The Banker and the Blackfoot, 117.

3. Alex Tesar, "Treaty 7," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Nov. 6 2019. Online.; Hugh A. Dempsey, "Treaty Research Report Treaty Seven (1877)", Treaties and Historical Research Centre, Comprehensive Claims Branch Self-Government, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 1987. PDF. pg. 20.

4. Treaty 7 Elders and Tribal Council, Walter Hildebrandt, Dorothy First Rider, Sarah Carter, The True Spirit and Original Intent of Treaty 7 (Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1996.), 68.

5. The True Spirit and Original Intent of Treaty 7, 74 - 75.

6. Alex Tesar, "Treaty 7," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Nov. 6 2019. Online.; Chamberlain, The Banker and the Blackfoot, 85.; Hugh A. Dempsey, "Treaty Research Report Treaty Seven (1877)", Treaties and Historical Research Centre, Comprehensive Claims Branch Self-Government, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 1987. PDF. pg. 15.

7. Chamberlain, The Banker and the Blackfoot, 116.

8. Edward Butts, "North-West Mounted Police," The Canadian Encyclopedia.

10. Isapo-Muxika

1. Hugh A. Dempsey, "Isapo-Muxika" in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Universite Laval, 2003. Online. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/isapo_muxika_11E.html

2. Chamberlin, The Banker and the Blackfoot, 110.

3. Hugh A. Dempsey, "Isapo-Muxika"

4. Hugh A. Dempsey, "Isapo-Muxika (Crowfoot)" The Canadian Encyclopedia, Dec. 1, 2020. Online. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/crowfoot

11. The Incomparable Jerry Potts

1. D. B. Sealy, "Potts, Jerry," in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Universite Laval, 2003. Online. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/potts_jerry_12E.html

2. Chamberlin, The Banker and the Blackfoot, 78.

3. D. B. Sealy, "Potts, Jerry."

12. Strike

1. Caroline and Lorne Brown, An Unauthorized History of the RCMP, 30.

2. Caroline and Lorne Brown, An Unauthorized History of the RCMP, 30.

3. William M. Baker, "The Miners and the Mounties: The Royal North West Mounted Police and the 1906 Lethbridge Strike," Labour/Le Travail, vol. 27, 1991, 66. Online. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25130245

4. Ibid, 60 - 61.

13. Manhunt

1. Hugh A. Dempsey, Charcoal's World (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978), 115.

2. Ibid, 127.

3. Ibid, 109 -110; Macleod, Sam Steele: A Biography, 153.

4. Macleod, Sam Steele: A Biography, 151; Hugh A. Dempsey, Charcoal's World.

5. Ibid, vii - viii.

14. Changing Times

1. Chamberlin, The Banker and the Blackfoot, 125.

2. Ibid, 126.

3. Ibid, 127.

4. Ibid, 289.

5. Ibid, 288.

6. Ibid, 289.

7. National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation - University of Manitoba "St. Paul's (Blood) Residential School," https://memorial.nctr.ca/?p=1519; NCTR - University of Manitoba "St. Mary's (Blood) Residential School" https://memorial.nctr.ca/?p=1517

8. Chamberlin, The Banker and the Blackfoot, 308.

Bibliography

Alex Boyd, "How the Cypress Hill Massacre of 1873 - Likely Canada's first mass shooting - helped create the RCMP," The Toronto Star, April 25, 2020. Online. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2020/04/25/how-the-cypress-hills-massacre-of-1873-likely-canadas-first-mass-shooting-helped-create-the-rcmp.html

Edward Butts, "North-West Mounted Police," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Dec. 6 2016. Online.

D. B. Sealy, "Potts, Jerry," in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Universite Laval, 2003. Online. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/potts_jerry_12E.html

First Nations Studies Program, "Royal Proclamation, 1763," Indigenous Foundations - University of British Columbia, 2009. Online. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/royal_proclamation_1763/#:~:text=The%20Royal%20Proclamation%20is%20a,what%20is%20now%20North%20America.&text=The%20Proclamation%20forbade%20settlers%20from,then%20sold%20to%20the%20settlers.

Fort Macleod History Book Committee, Fort Macleod - Our Colourful Past, Fort Macleod: Friesen Printers, 1977.

Gerry Burnie, "The 'Great March,' 1874" Interesting Canadian History, June 13, 2013. Online.

Greg Marquis, "The 'Irish Model' and nineteenth-century Canadian Policing," The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 25, No. 2 (1997): 208 - 209. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03086539708582998

Hugh A. Dempsey, "Isapo-Muxika" in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Universite Laval, 2003. Online. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/isapo_muxika_11E.html

Hugh A. Dempsey, "Isapo-Muxika (Crowfoot)" The Canadian Encyclopedia, Dec. 1, 2020. Online. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/crowfoot

Hugh A. Dempsey, "Mi'k ai'stoowa (Red Crow)," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Oct. 20, 2020. Online. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/red-crow

Hugh A. Dempsey, "Treaty Research Report Treaty Seven (1877)", Treaties and Historical Research Centre, Comprehensive Claims Branch Self-Government, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 1987. PDF.

J. Edward Chamberlin, The Banker and the Blackfoot - A memoir of my grandfather in chinook country" (Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), 25.,

James Finlayson, “Jottings on the March from Fort Garry to Rocky Mountains,” 1874. — Photocopy of handwritten account and typescript; from original in Library and Archives Canada, MG 29, E-58. PDF.

Jim Selby, "One Step Forward: Alberta Workers 1885 - 1914" in Working People in Alberta: A History, ed. Alvin Finkel, Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2012.

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation - University of Manitoba "St. Paul's (Blood) Residential School," https://memorial.nctr.ca/?p=1519; NCTR - University of Manitoba "St. Mary's (Blood) Residential School" https://memorial.nctr.ca/?p=1517

Roderick Charles Macleod, "Macleod, James Farquharson" in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003. Online. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macleod_james_farquharson_12E.html

Rod Macleod, Sam Steele: A Biography, Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2018.

Sarah Carter, "Categories and terrains of exclusion: constructing the "Indian Woman" the early settlement era in western Canada," Great Plains Quarterly 13, No. 3 (Summer 1993).

Stanley W. Horrall, The pictorial history of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Toronto, ON: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1973.

Treaty 7 Elders and Tribal Council, Walter Hildebrandt, Dorothy First Rider, Sarah Carter, The True Spirit and Original Intent of Treaty 7, Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1996.

William M. Baker, "The Miners and the Mounties: The Royal North West Mounted Police and the 1906 Lethbridge Strike," Labour/Le Travail, vol. 27, 1991. Online. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25130245