Walking Tour

From the Coal Pit to the Barbed Wire

How Internment Came to Fernie

Andrew Farris

Fernie & District Historical Society FMP_00785

Fernie's story of internment began in the coal mines. Before the First World War hundreds of Austro-Hungarians and Germans had settled in and around Fernie to work alongside other immigrants to mine coal from the East Kootenays. The great majority of them were ethnic Ukrainian, or Galician as they were then known. It was dangerous, back-breaking work for little pay. They worked at the whim of their employer, the Crows' Nest Pass Coal Company. When the world economy went into recession in 1913 hundreds of miners were laid off and left jobless.

Then the First World War started, and the miners from Germany and Austria-Hungary were officially designated 'enemy aliens.' The miners from Allied countries wondered why they had to share the scarce work with these 'enemy aliens' and soon they began to demand that they be fired. The government responded by arresting several hundred Austro-Hungarian miners and a few Germans and interning them at Fernie's ice rink, once located on the banks of the Elk River.

There they were kept for the summer of 1915, until they were transferred to a camp at Morrissey where the Austro-Hungarians (most of whom were ethnic Ukrainians) were forced to work in harsh conditions.

In this tour we'll dig into the story of internment at Fernie. We'll learn why the people from the multiethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire emigrated to Canada, and the discrimination they faced trying to build a new life in Canada. Then we'll see how economic headwinds combined with wartime xenophobia caused a breakdown in worker solidarity and the persecution of these men for no reason other than their place of birth.

We encourage you to view the Morrissey tour after you've completed the Fernie tour.

Route

This tour starts with a stroll down Fernie's 2nd Avenue. Then we will move to 3rd Ave and then 4th Ave by the courthouse and former Crows' Nest Pass Coal Company offices. Finally we will go down 5th Avenue towards the river's edge, where the ice rink once stood that would become the internment camp for the Elk Valley's 'enemy aliens' in the summer of 1915.

This project has been made possible by a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

1. The Founding of Fernie

Fernie & District Historical Society FMP_00590

ca. 1900s

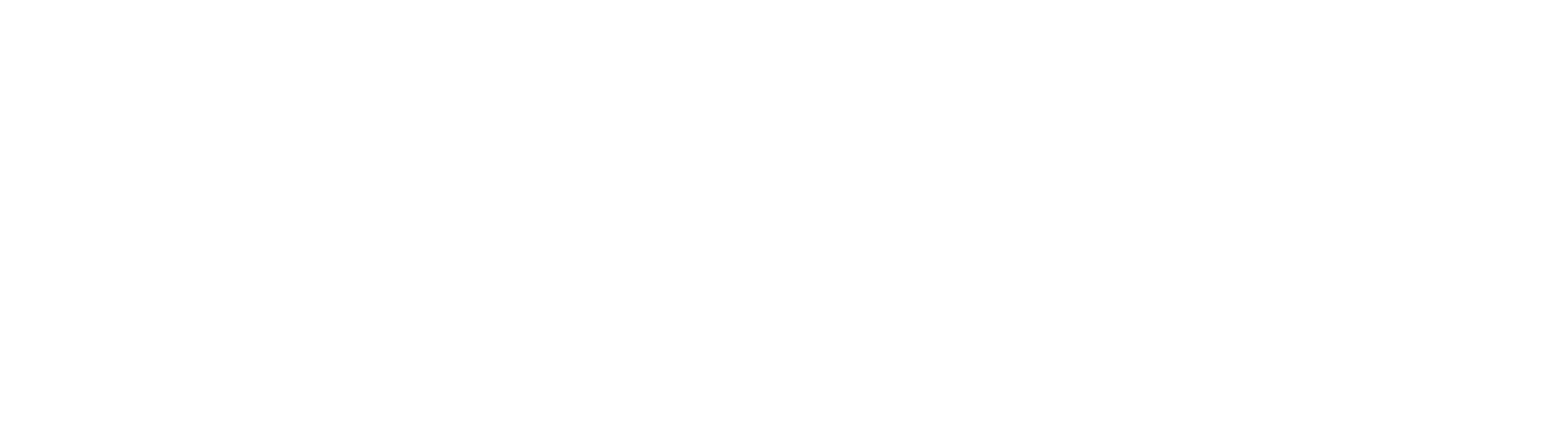

We begin our tour on 2nd Avenue, formerly Victoria Avenue, at the end of the 19th Century. In this photo a crowd has gathered around a horse drawn fire engine. When this picture was taken Fernie was just over 10 years old. Today, Fernie is best known as a haven for mountain bikers, skiers, and outdoor enthusiasts of every stripe. But that's not what attracted the people in this photo to this place: Most were drawn--directly and indirectly--by the Elk Valley's coal.

The Kootenays are home to some of the richest coal seams in Canada, and Fernie became a service centre for the mines that extracted it. Unlike mines today, which require relatively few workers, the coal mines of the Elk Valley required thousands of workers, and thousands more to provision them.

* * *

William Fernie, a miner, trapper, and rancher, saw the potential of the region's coal, and began advocating for a railway into the region that could allow people to flow in, and coal to flow out. It took 10 years, but by 1897 the railway was complete. William Fernie, along with two others, founded the Crow's Nest Pass Coal Company and soon opened mines at Michel, Coal, and Morrissey Creeks. The Elk Valley was open for business.

This development happened to coincide with Canada's Western Boom, which saw millions of immigrants flooding into the western provinces, to set up farmsteads, townships, forestry camps, and mines. In the Elk Valley, they established Fernie at the centre of the growing mine network, and it was formally incorporated as a City in 1904.

Though the city burned down in 1904, and then again in 1908, it rose from the ashes both times. By 1910 the population had grown to over 6,000, slightly larger than the population is today.1

Many of these people were immigrants from Britain, but Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier's immigration policy in the first decade of the 20th Century reached out to other parts of Europe too--especially Eastern Europe. These initiatives were successful, and by the outbreak of the First World War, there were thousands of Fernie residents and Elk Valley miners who had immigrated from Austria-Hungary, Russia, Italy, and Germany.

Many of these new arrivals worked in the mines, and as we will see, this quickly created tensions with the British miners.

2. The Terror of the Mines

1902

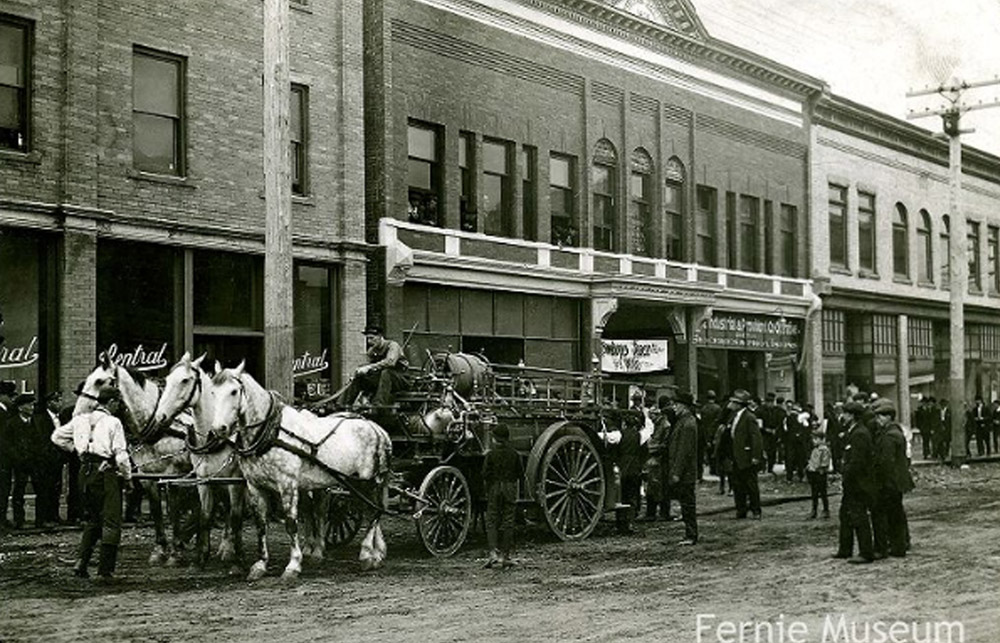

A solemn procession carries coffins down Victoria Avenue, victims of the 1902 Coal Creek mine explosion, located just east of Fernie. That disaster killed 128 miners, making it the third worst mining disaster in Canadian history.1 Disasters on this horrifying scale periodically punctuated life in these tight-knit mining communities, though workplace accidents resulting in injury and death were more or less everyday occurrences. The photo is a reminder of the grave risks the miners took when they descended into the pits.

As we shall see, the miners, and the conditions they worked in, played a central role in the story of Fernie's internment operations. The conditions were generally deplorable. The work was extraordinarily dangerous, they lived in shoddy accommodations, and they were exploited by the mine owners at every opportunity.

* * *

As unskilled labourers, these immigrants had basically three options when they arrived in Canada: homesteading, working on the railway, and working in the coal mines. As the historian K.L. Buckley notes, mining was usually the most attractive option since unlike homesteading it paid high wages, and, unlike railway work it meant they could live with their families year round.1

A study by Joanna Matejko of Polish miners in Alberta shows that almost all saw it as just a temporary solution. As one miner, Paul Pieronek wrote, he wanted "to make enough money working in the coal mines to return to Poland and buy more land and a house there."2

It's hardly surprising many of them didn't want to stay long. The work was dark, back-breaking, and terrifying. Yuriy Frolak, a Ukrainian miner in the Crowsnest Pass, recalled what it was like when he and his friends started mining: "The traumatic experiences of the seven boys [recently arrived from the Ukraine] in changing from farmers... to miners digging out coal from the bowels of the Rocky Mountains... are best left to the imagination of the reader."3

A miner's song popular in the Elk Valley at the time gives us a truly heart-rending snapshot of the terrors and anxieties these men and their families faced. It was called 'Don't Go Down in the Mine, Dad.'

"A miner was leaving his home for his work," "When he heard his little child scream;" "He went to his bedside, his little white face," ""Oh Daddy, I've had such a dream;" "I dreamt that I saw the pit all afire." "And men struggled hard for their lives;" "The scene it then changed, and the top of the mine" "Was surrounded by sweethearts and wives.""

"Don't go down in the mine, Dad," "Dreams very often come true;" "Daddy, you know it would break my heart" "If anything happened to you;" "Just go and tell my dream to your mates," "And as true as the stars that shine," "Something is going to happen today," "Dear Daddy, don't go down in the mine!"

"The miner, a man with a good heart and kind," "Stood by the side of his son;" "He said, "It's my living, I can't stay away," "For duty, my lad, must be done."" "The little one look'd up, and sadly he said," ""Oh please stay today with me, Dad!"" "But as the brave miner went forth to his work," "He heard this appeal from his lad;"

"...CHORUS…"

"Whilst waiting his turn with his mates to descend," "He could not banish his fears," "He return'd home again to his wife and child," "Those words seem'd to ring through his ears," "And, ere the day ended, the pit was on fire," "When a score of brave men lost their lives;" "He thank'd God above for the dream his child had."4

3. The Ukrainians

Fernie & District Historical Society FMP_00326

ca. 1910s

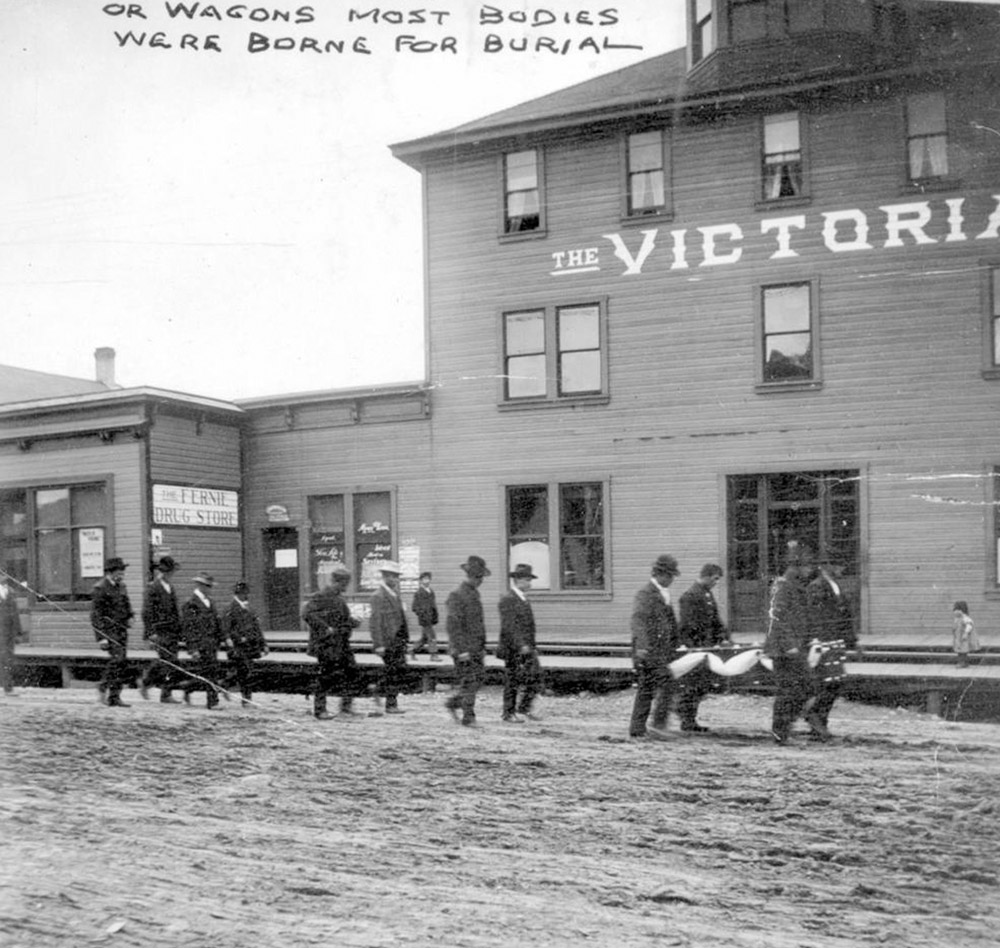

Snow blankets the streets in front of the old Bank of Commerce. Winter conditions in much of Canada were not so different from those in Ukraine. They were certainly more familiar to the hardy people of eastern Europe than the British immigrants who accounted for most of the early European settlers in this region.

Before the war, 12% of the miners in this region were from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.1 The great bulk of them were Ukrainian. From what we've seen, working in a coal mine in the Elk Valley would seem like a job only an insane person would willingly cross an ocean and a continent to take. Why did all these Ukrainians think it worthwhile to make the journey?

Most Ukrainians who emigrated to Canada were peasant farmers who came from the Austrian provinces of Galicia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia. At the frontier of the empire, they were easily neglected by an indifferent government. Urban underdevelopment and rural overpopulation were the defining facts of life in these provinces, which led to a downward spiral of poverty and hunger. Many young Ukrainians saw depressingly little hope for the future in their homeland.

Let's take a moment to understand the place they came from.

* * *

Ruled by the Habsburg dynasty, Austria-Hungary could trace its origins back to Charlemagne and the early Middle Ages. It was dominated by ethnic Germans from the capital of Vienna in the west, while the other 10 ethnolinguistic groups had varying levels of national consciousness and imperial recognition. Foremost amongst them were the Hungarians, who had won status as a semi-autonomous and equal part of the empire in the mid-1800s, adding '-Hungarian' to the empire's name.

Members of all 11 groups had immigrated to Canada in some numbers by 1914, but by far the largest were Ukrainian, or Ruthenian as they were then commonly known. Why was that?

The Ukrainians are a Slavic people who lived on exceptionally fertile and beautiful land, but in a dangerous geographic position at the edge of many empires--Most etymologists believe the word Ukraine has its origins in the Slavic word for "borderland."2

Frequent invasion and conquest from all points of the compass made for immensely challenging conditions to build an independent nation. By the 19th Century, Ukraine had been cleaved in half between Russia and Austria-Hungary, and both powers treated the Ukrainians as a potentially rebellious minority.

The Ukrainian portions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire were the north-eastern frontier provinces of Galicia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia. They were among the very poorest parts of all Europe.3 The sclerotic government in Vienna "deliberately" kept these regions underdeveloped to ensure they remained "an agricultural zone and marketplace for products from the industrially advanced western parts of the empire."4

The vast majority of Ukrainians were peasant farmers, and there was too little farmland to go around. A Ukrainian family needed 14 acres of land to subsist. Over two-thirds of the farms were less than half that size. A Galician worker's wages could start at a pitiful 5 cents a day.2 Despite their poverty, they were squeezed by the local aristocracy, who levied taxes and rents at eye-popping rates. The local elites sometimes acted as if the Feudal Era had never ended.

As the historian Pierre Berton writes:

The wealthy pahns (lords) owned not only the forests, meadows, and villages; they also owned the taverns, of which there were twenty-three thousand in Galicia. It was in the interests of the ruling class to keep the peasants drunk and underpaid. The consumption of liquor was stupendous: twenty-six litres a year for every man, woman, and child. One of the commonest words in the language was 'beeda', meaning misery. To the question "How is everything?" the usual reply was "Beeda."3

4. Coming to Canada

Fernie & District Historical Society FMP_00190

1915

A Boy Scout parade prepares to march down Victoria Avenue in 1915. The Scouts and the British flags flanking them reflect how loyalty to the British Empire and the embrace of all things British were the bedrock principles of Canadian culture at that time.

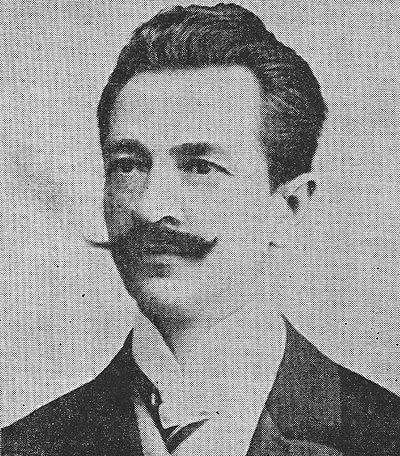

At the time many countries were competing for immigrants: Australia, Argentina, the United States, Brazil--why did so many Ukrainians choose to emigrate to Canada? Part of the answer was the work of Dr. Joseph Oleskiw.

Dr. Joseph Oleskiw, the biggest Ukrainian promoter of emigration to Canada.

* * *

At the time the first groups of Ukrainians were being enticed to emigrate by outlandish promises from agents of the steamship companies--though not to Canada, but Brazil. The first reports back from these emigrants to South America horrified Oleskiw. The peasant farmers were lied to and cheated every step of their journey to the farms in Brazil, where they arrived broke and were treated "little better than slaves."1

Oleskiw looked at Canada as an alternative destination. In 1895 he toured the country by rail, and marvelled at the vast prairie wilderness, which reminded him of the fertile soils of his native land. He met with the Canadian government to propose a carefully organized immigration scheme, where Oleskiw would handpick peasant families that could support themselves. At the time the government was not particularly interested, and his plan was shelved.

The professor took matters into his own hands. He returned to Galicia and distributed pamphlets extolling the virtues of Canadian immigration, and promising 160 acres of free land to any family that could build a home upon it and live there for three years. To the farmers who toiled on miniscule plots, such an offer was scarcely credible. Rosy reports sent back from early migrants to Canada however seemed to confirm that the Dominion was the real deal.2

Oleskiw's pamphlets were passed from village to village, and word of opportunity in Canada spread like wildfire.

Oleskiw did succeed in organizing several hand-picked family groups of farmers to emigrate to the prairies and set up villages, but the effect of his pamphlets far surpassed his tidy scheme. He had started a movement that he could no longer control. By the early 1900s tens of thousands of Ukrainians were making the long and perilous journey; first to ports like Hamburg, then a month-long ocean passage crammed into steerage on a steamer, and then a teeth-chattering train journey from Quebec across the Canadian Shield and into the endless prairie.

Unfortunately, along the way these emigrants suffered from the same unscrupulous steamship agents, corrupt border authorities, and canny scheisters of every kind trying to separate them from their hard-earned money.

Furthermore, many of these immigrants were not the reasonably well-off and respectable farmer families that Oleskiw had in mind. Many were single young men looking for opportunity, who found themselves cheated out of all their meagre savings by the time they reached the Canadian West. These were the kind of men who wound up working in the coal mines of the Elk Valley.

5. Life Before the War

Fernie & District Historical Society FMP_00106

ca. 1910s

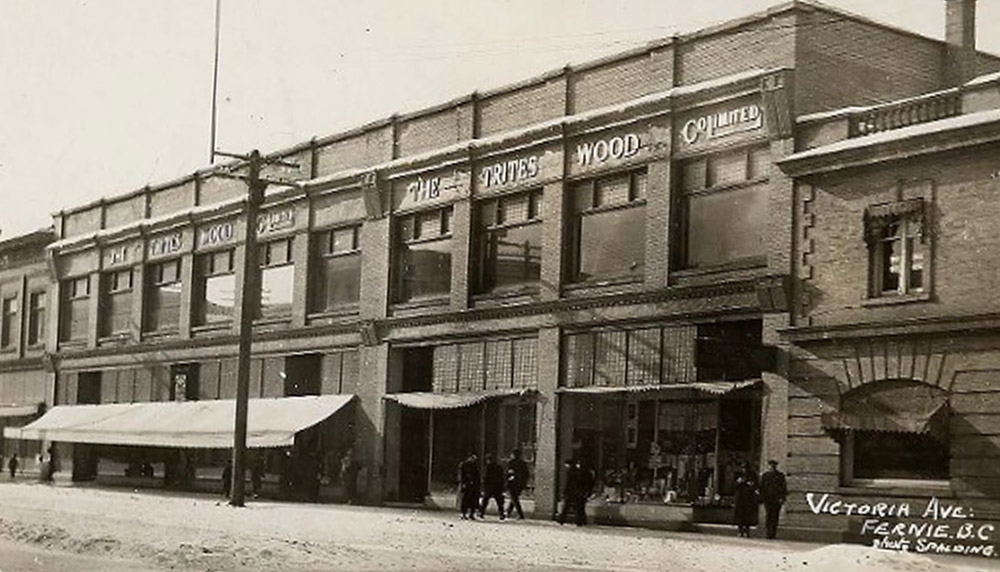

The Trites-Wood Department Store opened in 1903 as the premier department store for the people of Fernie. It would remain a mainstay of Victoria Avenue (today's 2nd Avenue) until its sale in 1970. This handsome brick building was built in 1908, after the previous store was destroyed in the 1908 fire, and the one before that destroyed in the 1904 fire.1

Department stores like this carried everything from food to clothing to hardware, and could provide most of the necessities of daily life. This particular store's target market was the burgeoning Anglo-Canadian middle class of Fernie, the clerks, mine managers, and bureaucrats. The company also catered to the miners with branch stores at the various pitheads, offering more basic amenities. Since the Trites-Wood Company had a virtual monopoly on supplies for the miners, they were able to charge exorbitant prices.

This was but one aspect of the unfair conditions the miners were forced to work under. To seek redress many miners joined unions. The Ukrainians especially sought worker's solidarity through organizing. But as we will see, they were not accepted with open arms by their Anglo-Canadian comrades.

* * *

Most of the miners and their families (if they had families with them) lived in housing near the pitheads provided by the company. A union representative of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) described the state of housing for miners in the Crowsnest Pass before the war:

Shacks are occupied principally by half- breeds and foreigners- Austrians mainly... The other night when I visited there, there was 14 of them in it, and it was a very dilapidated structure for men - mainly paper and logs. Very small for the amount of men in it. Poor ventilation and very dirty, as there was no janitor to do with anything of that kind. Now come to the bunkhouse... it holds from 60 to 70 men. It's divided by a thin partition and the door opens in it too... It is just a shell, unplastered, two ply of lumber on the outside, two by four, open on the top, never had any ventilation in it.3

He noted that these men had been living in these conditions since February through the tail end of a Rocky Mountain winter.

Conditions like this politicized many Ukrainian miners. They had support from the Robochyi Narod (The Working People), a Ukrainian language socialist newspaper started in Winnipeg in 1908. The Robochyi Narod encouraged Ukrainian workers to join revolutionary American unions making inroads in the Kootenays, like the International Workers of the World (IWW), and the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). Ukrainian workers also formed their own political organization, the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party of Canada (USDP).

The USDP, for it's part, embarked upon an ambitious program to aid Ukrainian workers. They "established relief programs for downtrodden workers in case of illness, accident or injury at work. The organization came out against predatory lending, the problem of personal debt, and taxes on the working class. It also demanded an increase in the minimum wage and the institution of a 44-hour work week."4

6. Expedient Racism

Fernie & District Historical Society FMP_00369

1946

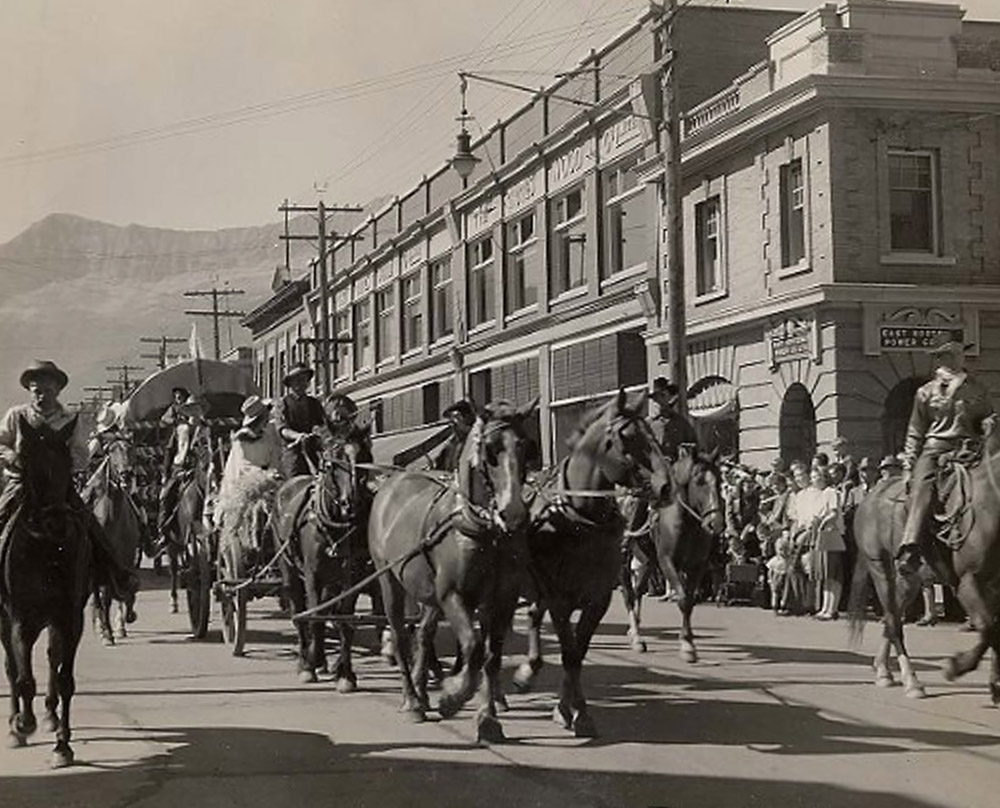

A parade goes down Victoria Avenue in the post-war era, with a particularly American-influenced Old West style cowboys and covered wagon. Back in 1914 the culture of Fernie had yet to become very Americanized and was instead completely dominated by British culture. The name 'Victoria Avenue' itself speaks volumes about Fernie’s establishment as an outpost of the British Empire.

The Ukrainians came from a radically different culture than the dominant British one, and it was more or less taken for granted by everyone--even the Ukrainian nationalist Dr. Oleskiw--that the new settlers would quickly assimilate into this Anglo-Canadian culture.1

Widely accepted Victorian notions of race placed different ethnicities on a racial hierarchy, with Western and Northern Europeans at the top, and the Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe quite a few rungs further down.

Mass immigration from Eastern Europe was one of the signature policies of the Liberal government of Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier. His opponents, seeking political advantage, found in the Ukrainians a useful cudgel to beat Laurier with. They could hurt Laurier by whipping up racist fears of Slavic immigrants.

These actions had ugly results. An editorial in the Belleville Intelligencer wrote "The Galicians, they of the sheepskin coats, the filth and the vermin do not make splendid material for the building of a great nation."2

By 1914, the time spent caricaturing the Eastern Europeans as a racial 'other' had left a strong residue across broad swathes of Canadian society. The implicit racism towards the Ukrainians hardened the hearts of many Canadians to their plight, and made the mass persecution and imprisonment of this and other Eastern European minorities all the more feasible and widely accepted.

* * *

However, as these new immigrants poured into the country, the opposition press went into overdrive demonizing them. They were accused of being filthy, lazy, and prone to crime.

In fact quite the opposite was true.

Once they began homesteading, they set up immaculately clean villages of white plaster homes that impressed visitors.

Their industriousness became plain to anyone who actually went to see them, and their farms were soon producing enormous amounts of wheat and other crops, helping turn the Canadian prairies into one of the world's breadbaskets, just as Ukraine was considered the breadbasket of Europe.

As for the criminal tendencies, newspapers published lurid stories of crimes committed by Ukrainains under headlines blaring "GALICIAN HORROR." In a typical example, in 1899 the Winnipeg Telegram alleged that a woman was murdered by a Galician in Brandon, MB. The political framing of the reporting was not subtle:

Another horrible crime committed by the foreign ruffians whom Mr. Sifton is rushing into this country... In order that Mr. Sifton may keep his Liberal Party in power by the votes of ignorant and vicious foreign scum he is dumping on our prairies, we are to submit to have our nearest and dearest butchered on our doorsteps.4

As was typical of these reports, it turned out to be a lie. The murderer was an English woman, not a Ukrainian.

Crime statistics from Winnipeg in 1900 show that 'Galicians' accounted for 9 out of 1,205 convictions--some 0.07%. The widespread stereotype of Ukrainian criminality was false. Nevertheless, as Pierre Berton points out, "the impression of Galician madmen murdering defenceless Canadian women was hard to erase."5

As is usually the case with racism, such attitudes were often dispelled by actual exposure to the people in question. Dr. R.H. Mason, who was initially a staunch opponent of Ukrainian immigration visited one of their towns. Expecting to find dilapidated hovels, his visit was a "revelation." The Ukrainians, he wrote, were "worthy, industrious, sober, and ambitious to make homes for themselves."

W.M. Fisher, a senior manager at a major mortgage company in Edmonton had a similar experience: "the Galicians against whom I was prejudiced before my visit... I found to be a most desirable class of settlers, being hard working, frugal people and in their financial dealings honest to a degree."6

Unfortunately, fairly few Canadians had much interaction with Ukrainians, and their knowledge of them came primarily from what the press printed about them.

7. Fractured Labour Movement

Fernie & District Historical Society FMP_00150

1909

A group of workers from United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners Local 1220 celebrate Labour Day in front of the Crow's Nest Pass Company office in Fernie. At right is a worker's parade float consisting of a gazebo pulled by two cheerfully decorated horses. Just behind the horse you can see an American flag, and also--more interestingly--a German flag. Just a few years later displaying a German flag like that would have been unthinkable.

The Austro-Hungarians (that is, mostly Ukrainians) in the Fernie region struggled to gain acceptance in the wider Canadian labour movement. The existing xenophobia of the Anglo-Canadian miners towards them was exacerbated by a recession in 1913 that created stiffer competition for scarce work. The outbreak of war created a tinder box that left miners from the Habsburg Empire in peril--and with precious few friends to call upon.

* * *

By 1914 the Anglo-Canadian mistrust of the Austro-Hungarians was compounded by a deep economic recession that left many miners out of work or working for reduced wages. Between 1913 and 1915 coal production by the Crows' Nest Past Coal Company fell from 1.3 million tons to 850,000 tons. Mass layoffs ensued, and the payroll fell from 1,965 men to 1,183. This left 782 men out of a job.2

Then the war happened. Two weeks after the British Empire went to war with Germany and Austria-Hungary, the Canadian government passed the War Measures Act. The act designated those born in enemy nations as "enemy aliens." The press fanned hysteria about spies, saboteurs, and fifth columnists hiding amongst these 'enemy aliens', and these fears quickly spread to the coal pits.

Some of the claims bordered on the ludicrous, such as the allegation that Austro-Hungarian saboteurs were responsible for the Hillcrest mine disaster in the Crowsnest Pass. The disaster occurred on June 19, 1914, when a pocket of methane exploded and killed 189 miners, making it the deadliest mining disaster in Canadian history. The inconvenient fact that 42 of the dead were Austro-Hungarian was ignored. Also ignored was the fact that the disaster happened almost two months before Austria-Hungary and Canada went to war--even a week before the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo beginning the slide toward war.3

The situation was not helped when the USDP refused to follow along with almost all other Canadian labour organizations and rally behind the flag. Instead they fiercely opposed the war. A USDP editorial in the Robochyi Narod wrote "The horrible indigence and hunger of workers has not ended... Now there is an all-European war, which will further the hunger and poverty of workers, claim many victims, and fill the rivers with worker's blood."4

Given what we know today about how the War To End All Wars turned out, we can only recognize this as an exceedingly brave and principled stand. However, to those Canadians swept up in the patriotic hysteria of 1914, this smacked of treachery.

8. Where Loyalties Lie

Fernie & District Historical Society FMP_00691

ca. 1910s

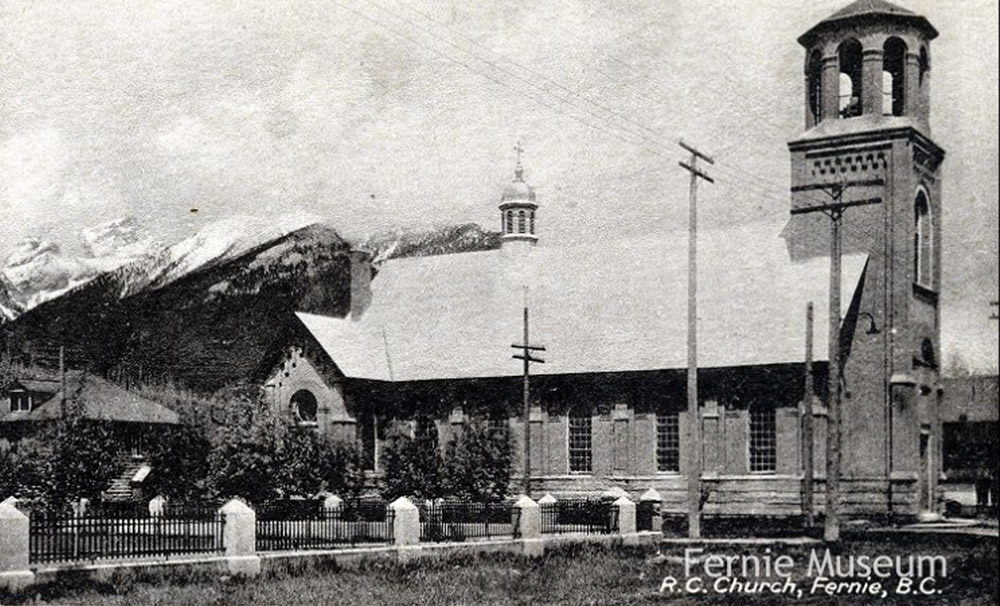

The Holy Family Parish church was built in 1911 for Fernie’s Roman Catholic community--who were primarily Italian. Most of the Anglo residents of Fernie were Protestant, while the sizable Italian and Ukrainian communities were Roman and Greek Catholic respectively. It was a significant cultural divide that became a political one when war came.

There was a week-long period between Austria-Hungry's declaration of war on Serbia on July 28, and the British Empire's entry into the conflict on August 4. In that brief interlude a prominent Ukrainian clergyman in Canada, Bishop Nykyta Budka, "with more haste than good judgement," told Ukrainians in Canada to return to Austria-Hungary to join the military.1 When the British entered the conflict, Budka quickly renounced his support for the Austro-Hungarian cause, but by then the damage had been done.

For the rest of the war, despite many protestations of loyalty, the Ukrainian community found itself the subject of suspicion and contempt. The Ukrainians who came from Austria-Hungary were branded 'enemy aliens' and had their rights severely curtailed.

Ultimately news about Canada's mistreatment of the non-German 'enemy aliens' got out and became an international embarrassment. In February 1915 the British Colonial Office felt it necessary to request that Canada give preferential treatment to "special classes" of aliens including "the following races which are considered to be hostile to Austro-Hungarian rule: Czechs, Croats, Italians, Poles, Roumanians, Ruthenes [Ukrainians], Serbs, Slovaks and Slovenes."2

The request was ignored.

* * *

T.A. Wroughton, the North West Mounted Police (NWMP) Superintendent in Alberta, reported to his superiors that the 'enemy aliens' were a nonissue:

Since the war broke out, I have had reports submitted to me by all the detachments in reference to alien enemies. The general feeling amongst Germans and Austrians would appear to be one of indifference in most cases, but in others where this is not so the risk of making any demonstration in favour of their own countries seems to be fully realized.4

Wroughton investigated frequent reports of 'enemy aliens' showing sympathy to their mother countries, or doubting the Canadian war effort. He wrote:

The result of enquiries into complaints of this kind is almost invariably the same as in this case. It is the foolish, unthinking and ignorant among the British themselves who are really at the bottom of all the trouble. They goad the aliens to such an extent it is not to be wondered at that they reply in kind.5

The Ukrainians had little reason to be loyal to the Habsburg monarchy. A group of Ukrainian Canadian newspaper editors tried to explain their predicament to the Canadian public:

The Ukrainians of Western Canada have found themselves heavily handicapped since the outbreak of the war by the fact of their Austrian birth... Many have been interned, though they are no more in sympathy with the enemy than are the Poles, for they are as distinct a nationality which hopes to emerge from the war in the enjoyment of a wide measure of national autonomy... And why? For only one reason, that they were so unhappy as to be born into Austrian bondage.6

As a rare sympathetic Anglo-Canadian commentator wrote, "Bear in mind that the great majority of these people are only enemies in a technical sense, being about as loyal to Hohenzollern or Hapsburg as a [Irish] Sinn Feiner is to the British Empire."7

None of it mattered. If anything, the non-German 'enemy aliens' would ultimately receive even worse treatment than their German counterparts, upon whom the war was widely blamed.

9. The War Intervenes

Fernie & District Historical Society FMP_00785

1923

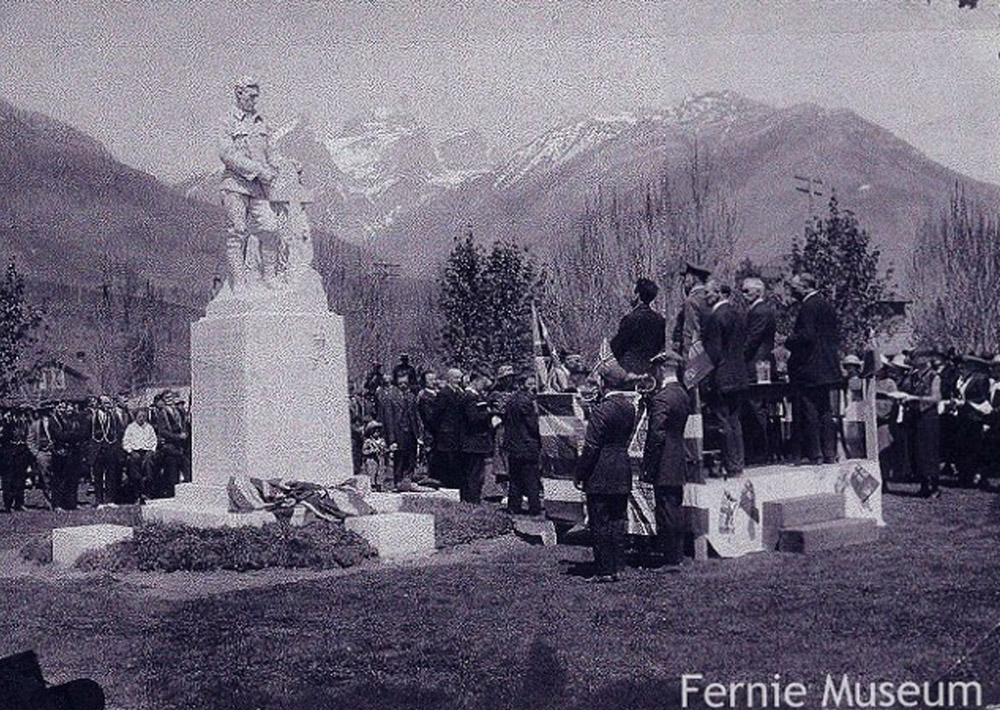

A solemn crowd gathers on the Courthouse grounds for the unveiling of Fernie's cenotaph after the First World War. The monument commemorates the over 1,100 young men from Fernie who went and fought in the war. Dozens of them died, and dozens more were maimed.1 The sculptor of this cenotaph won a design competition with this brooding soldier, though he was fired when it was discovered he had German ancestry.2

As soon as the War Measures Act categorized those from enemy nations as 'enemy aliens', many businesses across Canada began firing all their 'enemy alien' workers. In Fernie however, this was not generally the case. The 1911 census showed that 480 out of 3,981 miners working in the Crowsnest Pass self-identified as Austrian, and the mine owners were reluctant to dismiss such a large portion of their workforce.3

The mine owners came under intense pressure from the workers from Allied nations to remove the Austro-Hungarians. The reasons for this were more cynical than anything. The recession had left hundreds of miners from Allied nations jobless, and they were infuriated to see the 'enemy aliens' continuing to work. An official reporting to the Minister of Labour wrote that the prevailing attitude amongst the Allied miners was "if they can get 300 of these [enemy aliens] out of the way it will mean another day's work each for those left."4

Nevertheless, wartime developments gave patriotic cover to the miners to intensify pressure. The baptism of fire of the Canadian Corps at the Second Battle of Ypres, the sinking of the passenger liner SS Lusitania, and the Italian entry into the war on the Allied side, escalated tensions in the Elk Valley's mines to a fever pitch.

* * *

The war clearly wasn't over by Christmas, but several events in April and May 1915 disabused Canadians of the notion that this would be a quick, painless, and glorious war. It was to be, in actual fact, a near-apocalyptic total war that required Canadian society to mobilize entirely to grind the enemy down to utter destruction. It was to be a war in greater scale, intensity, and carnage than the world had ever seen.

The first of these events was the Second Battle of Ypres. The first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) to reach the front lines in France suddenly found itself in the crosshairs of a German offensive on April 22, 1915. It was the first major action by the Canadians in the war.

It also happened to be the first time poison gas was used in the history of warfare.

When the Germans unleashed clouds of chlorine gas on the Canadian lines, many Canadian soldiers, caught by surprise and lacking gas masks, urinated on their handkerchiefs and wrapped them over their faces to try and neutralize the gas. Many others drowned in their own blood. Against all odds, the Canadians managed to fend off the assault, but the cost was stupendous. In the space of a couple days over 6,500 men became casualties, around a quarter of the CEF's strength.5 Such casualty rates were largely unknown in modern warfare, and came as a horrifying shock to the public. The use of poison gas, which was a direct violation of the Hague Conventions on the Laws of War, was an outrage that incensed opinion in Canada.

The next blow came soon after, on May 7, when the SS Lusitania was sunk by a German U-Boat. 1,193 of the 1,960 passengers and crew drowned.6 The sinking of a civilian vessel without warning was another direct violation of the laws of war. Germany claimed the vessel was carrying ammunition to support the Allied war effort, which would have made such an act legal. The British Government vehemently denied the claim, and a major propaganda campaign was launched to constantly remind people of this barbaric act of Teutonic treachery. It wouldn't be until over 60 years later that declassified documents showed the Lusitania was indeed carrying an enormous amount of munitions and war materiel, making it a legitimate target.7

Nevertheless, a large number of Canadians had drowned, including 15 Victoria residents. One of them was the son of a former premier, and the grandson of Robert Dunsmuir, the richest man in British Columbia and scion of the family that owned almost all the mines on Vancouver Island.7

This sparked a wave of violent rage against the 'enemy aliens', especially in British Columbia. Over two nights a mob of 2,000 rioted across Victoria, destroying a number of German-owned businesses. Workers at the Dunsmuir-owned collieries around Nanaimo and Cumberland went on strike, demanding the immediate dismissal of every 'enemy alien' working alongside them.

The Second Battle of Ypres and the Lusitania told Canadians that this was no ordinary war. The gloves were off.

The Vancouver Sun took the lead in stridently demanding every 'enemy alien' be incarcerated, a measure that would have led to the arbitrary imprisonment of hundreds of thousands. It's hard not to conclude that the paper's editors implicitly advocated for vigilante violence against any people who originated from an enemy nation. In the aftermath of the riot, they wrote:

Although more than a week has passed since the sinking of the Lusitania, and the agitation for the internment of all enemy aliens in Canada, no official notice has been taken... It then remains for the people of Canada to say whether or not they wish to expose the lives of women and children to these fiends in human form. The Sun is not seeking to take any credit for the agitation which has swept the city during the past week. We feel that it is simply a matter of duty which every man in this city and in this country should perform.8

The coal miners' strike in Nanaimo panicked the provincial government, who feared the loss of coal production would harm Canada's war effort. Acting provincial premier, William Bowser, acceded to the worker's demands and ordered the mass internment of the miners working around Nanaimo.

The miners in Fernie took notice.

One more event helped bring events in Fernie to a boil: Italy's entry into the war on the Allied side just a couple weeks later, on May 23, 1915. Italy had actually been allied to Germany and Austria-Hungary (the Triple Alliance) but the Italian government had cynically fielded offers from both sides to see who would give them a better deal. When the Allies promised Italy more territory (large chunks of ethnic-Italian territory in Austria-Hungary) the Italians reneged on their treaty and joined the Allies. The Italians quickly launched a bloody and futile offensive against the Dual Monarchy, the first of what would ultimately be 11 disastrous Battles of the Isonzo.

A very large contingent of Italian miners worked in the Elk Valley and Crowsnest Pass--slightly more than Austro-Hungarians in fact.9 As a result the Italians in the Elk Valley added their voices to the calls for the immediate removal of all Austro-Hungarians from the mines.

All these events demonstrated to the government that maintaining social stability, especially in an essential industry like coal, would require drastic and unprecedented action. Within days events in Fernie would come to a head.

10. The Allied Miners' Revolt

Fernie & District Historical Society FMP_00235

ca. 1925

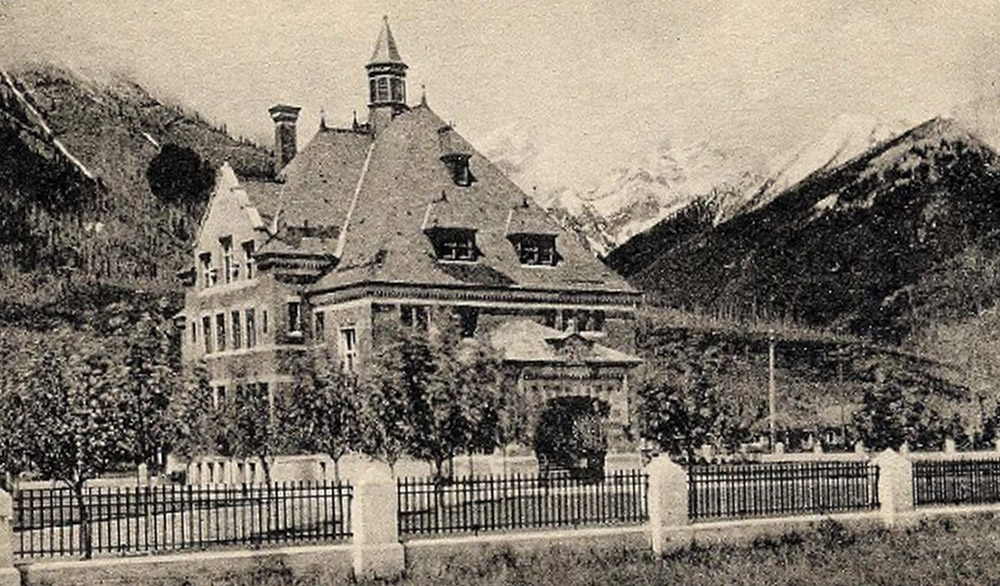

This photo shows the Fernie courthouse that was completed in 1909. Curiously, it was built in the distinctly Canadian Chateau style of architecture popular with the grand railway hotels of the time. Notice the turret, steep roofs, and stone facades particular to this style.

It was here that 600 miners from Allied nations, mostly British, but also Italian, French, and Belgian, gathered on June 8, 1915, to hold a heated debate over removal of the Austro-Hungarian and German miners from the mines.1

Two union representatives of the United Mine Workers of America tried to dissuade the miners, arguing that ethnic splits would weaken the union's power in the face of the mine owners. Their pleas were apparently met with derision. The intensification of the war and the deepening recession had shattered the class solidarity of the miners in the Elk Valley.

The miners approved a resolution that read "Resolved that the men as Britishers, and others who are friendly, will work, but not under present conditions, that is, not with alien enemies."2

The Crows' Nest Pass Coal Company refused, fearing the loss of coal production. The BC Government on the other hand felt that a strike by the miners from the Allied nations was a greater threat to production and to public order. They didn't want repeats of the anti-German riots that had just rocked Victoria.

On June 9, BC Attorney General William Bowser ordered that all the 'enemy alien' miners who were unmarried or married without children were to report to the courthouse here for internment. They were allowed to bring a blanket and some belongings.

* * *

Caustic comment has been evoked by the fact that at present there are in the neighbourhood of 200 Austrians and Germans working in the Rogers Pass tunnel... The suggestion is made that if... the contractors desire to show their patriotism they should let the alien enemies go and hire British subjects in their places, as there are many unemployed ready and willing to fill the vacancies.

It is felt that the action of the contractors is calculated to kill patriotism among the working classes and cause hard feelings against the enemies of the empire who are in the country. Moreover, the danger to the British workers is great, for these aliens could, if they so desired, procure dynamite from the magazines and blow up the entire workings.4

The miners' strike threat led to a flurry of telegraphs between the authorities in Fernie, the provincial government in Victoria, and the dominion government in Ottawa.

BC's Attorney-General didn't take long to issue the order. He was egged on by a gleeful press. "Why stop at the internment of miners only?" asked the Vancouver World. "There are many other classes of aliens in British Columbia who for the benefit of the province and for their own welfare, would be much better interned. We commend the idea to the Attorney-General's immediate consideration."5

Bowser had already sanctioned the internment of enemy alien miners in Nanaimo, so it was no big step for him to do the same in Fernie. There was a problem however: the Nanaimo miners were in provincial jails, whereas the Fernie ones were under military guard, putting them under federal jurisdiction.

The situation in Fernie was deeply worrisome to Ottawa. A disruption in coal production "was to be avoided at all costs," Kordan writes. "From the government's perspective, workers were not to be distracted from the war effort or their work and were to be dissuaded from participating in actions that would threaten either."6

However, the federal government had a major problem: the wholesale internment of workers who "gave no grounds for arrest," was clearly illegal under Canadian law.7

The government had already interned thousands of select 'enemy aliens' that could be deemed a national security risk in the broadest possible sense, or were unemployed--already highly questionable under international agreements but still legal under the War Measures Act. International reporting about this in early 1915 had embarrassed Canada and led to a chiding from the British government. This time they wanted to do things by the book.

They found a simple--and draconian--legal solution. On June 26, an Order in Council was issued that allowed internment of all "enemy alien civilians" where there was "serious danger of rioting, destruction of valuable works and works and property." It also revoked Habeas Corpus--the right to a fair trial.8

In effect, this meant that if people refused to work with 'enemy aliens', then those aliens could be arrested, interned, deprived of their right to trial, and compelled to do hard labour under armed guard for an indefinite length of time.

Unsurprisingly, word of what had happened in Fernie quickly spread to coal pits across the country, and a wave of mass firings of Austro-Hungarians and Germans followed-- some 2,000 in Alberta alone.21 Many of them were dispatched to internment camps.

Ironically, within a year there would be a massive labour shortage because so many men had been sent to fight in France.

11. Interned at the Ice Rink

Fernie & District Historical Society

1916

This was once the location of Fernie's ice rink on the banks of the Elk River. As we can see, this low-lying area wasn't the best spot for a rink, and it was occasionally flooded when the river swelled and burst its banks.

On June 9, 1915, 108 Austro-Hungarians and Germans from around Fernie were marched here from the courthouse to begin their internment. The rink would serve as a temporary internment camp while the provincial and federal governments bickered over what to do with them.

They were soon joined by other 'enemy aliens' from across the Kootenays which brought the total to 290 internees. They were guarded by 30 soldiers from the 107th East Kootenay Regiment under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William MacKay.1

The ice rink was ill-equipped to hold hundreds of men. They were set to work building their own prison, erecting barbed wire fences, clearing land, and digging latrines. The internees slept on the hard floor and prepared their own meals, supplemented by food delivered from family and friends who lived nearby.2 Close to the community and not yet forced to work, life at the ice rink was to be a much more pleasant experience than the forced labour camps that followed.

* * *

Caustic comment has been evoked by the fact that at present there are in the neighbourhood of 200 Austrians and Germans working in the Rogers Pass tunnel... The suggestion is made that if... the contractors desire to show their patriotism they should let the alien enemies go and hire British subjects in their places, as there are many unemployed ready and willing to fill the vacancies.

It is felt that the action of the contractors is calculated to kill patriotism among the working classes and cause hard feelings against the enemies of the empire who are in the country. Moreover, the danger to the British workers is great, for these aliens could, if they so desired, procure dynamite from the magazines and blow up the entire workings.4

The miners' strike threat led to a flurry of telegraphs between the authorities in Fernie, the provincial government in Victoria, and the dominion government in Ottawa.

BC's Attorney-General didn't take long to issue the order. He was egged on by a gleeful press. "Why stop at the internment of miners only?" asked the Vancouver World. "There are many other classes of aliens in British Columbia who for the benefit of the province and for their own welfare, would be much better interned. We commend the idea to the Attorney-General's immediate consideration."5

Bowser had already sanctioned the internment of enemy alien miners in Nanaimo, so it was no big step for him to do the same in Fernie. There was a problem however: the Nanaimo miners were in provincial jails, whereas the Fernie ones were under military guard, putting them under federal jurisdiction.

The situation in Fernie was deeply worrisome to Ottawa. A disruption in coal production "was to be avoided at all costs," Kordan writes. "From the government's perspective, workers were not to be distracted from the war effort or their work and were to be dissuaded from participating in actions that would threaten either."6

However, the federal government had a major problem: the wholesale internment of workers who "gave no grounds for arrest," was clearly illegal under Canadian law.7

The government had already interned thousands of select 'enemy aliens' that could be deemed a national security risk in the broadest possible sense, or were unemployed--already highly questionable under international agreements but still legal under the War Measures Act. International reporting about this in early 1915 had embarrassed Canada and led to a chiding from the British government. This time they wanted to do things by the book.

They found a simple--and draconian--legal solution. On June 26, an Order in Council was issued that allowed internment of all "enemy alien civilians" where there was "serious danger of rioting, destruction of valuable works and works and property." It also revoked Habeas Corpus--the right to a fair trial.8

In effect, this meant that if people refused to work with 'enemy aliens', then those aliens could be arrested, interned, deprived of their right to trial, and compelled to do hard labour under armed guard for an indefinite length of time.

Unsurprisingly, word of what had happened in Fernie quickly spread to coal pits across the country, and a wave of mass firings of Austro-Hungarians and Germans followed-- some 2,000 in Alberta alone.21 Many of them were dispatched to internment camps.

Ironically, within a year there would be a massive labour shortage because so many men had been sent to fight in France.

12. The Move to Morrissey

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

1915

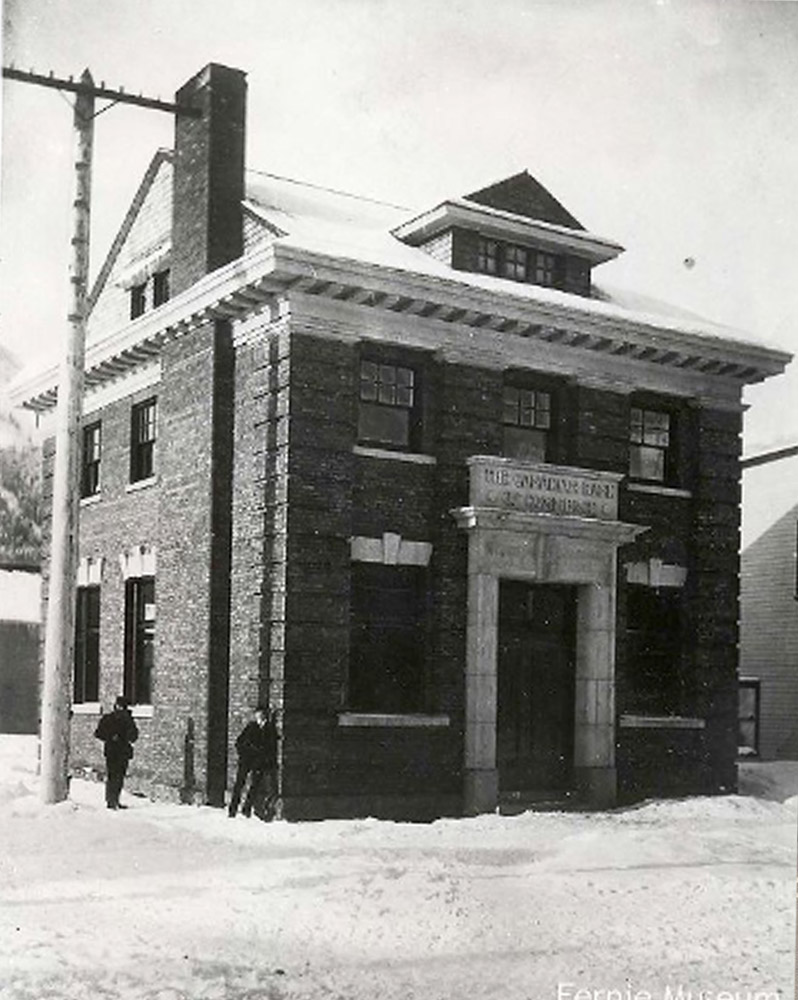

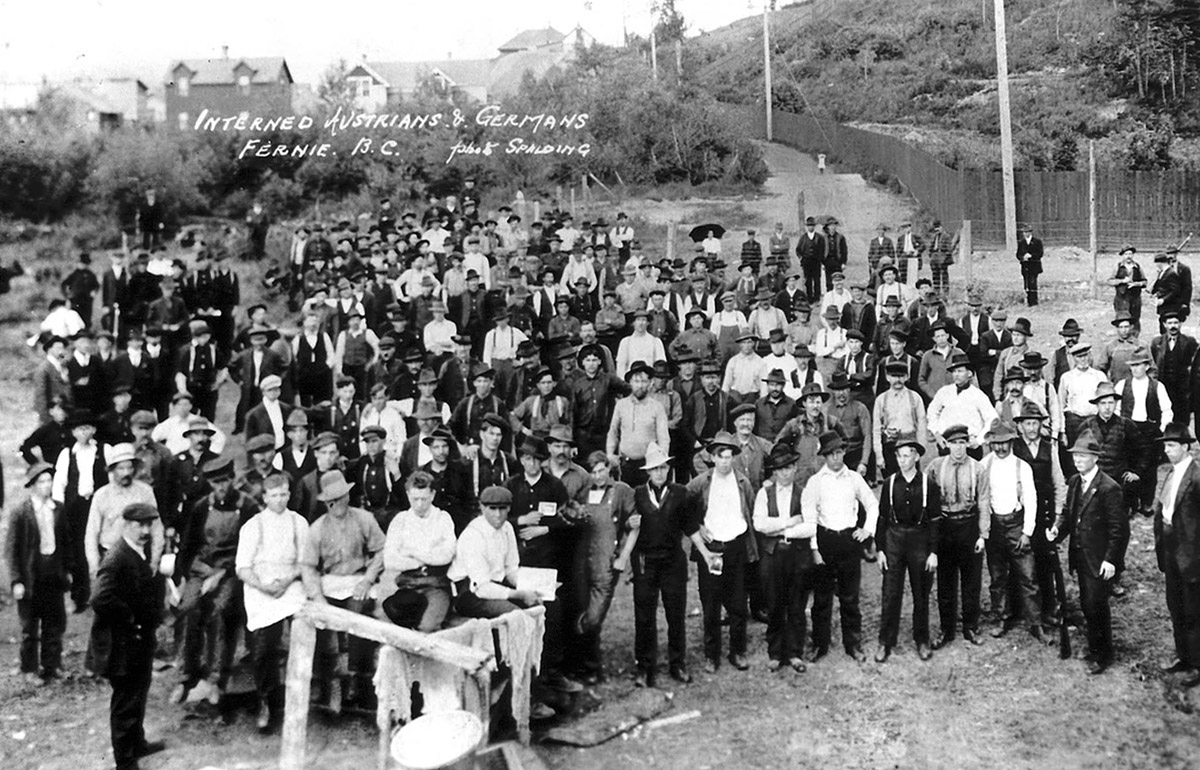

A photo of the internees gathered for a group photo on the parade ground by the ice rink in the summer of 1915. You can see the barbed wire fence at the back right, with some civilians on the other side curiously looking in.

Lt. Col. MacKay found himself in the awkward situation of simultaneously opposing this internment on moral grounds and being commandant of the internment camp. He acted on his principles and personally reviewed the files of every internee, releasing as many as could be justified to his superiors. This amounted to over half of the men. They were mostly Ukrainians, Czechs, and Hungarians who all "willingly took the prescribed oath, and signed a pledge to report at all times when required to do so by the police."1

This left just 157 Austro-Hungarians and 7 Germans in his custody.2

The ice rink was only intended to be a temporary solution, but they couldn't be transferred to the camps at Vernon and Fernie--they were already overflowing. They cast around for suitable sites for a more permanent camp and settled on the recently abandoned townsite at Morrissey.

Morrissey is located 13 kilometres south of Fernie along Highway 3. The coal mine there had been abandoned in 1909, and almost all the residents of the small townsite there had moved away. Many of the buildings still stood however, enough to house over 1,000.3 The internees could be accommodated here relatively easily, and put to work building the road from Fernie to Elko.

At the end of September and beginning of October, 161 internees were transferred from Fernie's ice rink to the camp at Morrissey, along with 100 guards.4 This was to be the next stage of an ordeal of forced labour and abuse that these men were to endure. In some cases it would last for five years.

* * *

Donate Now

If you enjoyed this free content, we ask you to consider making a donation to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, which is providing urgently needed humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian people are heroically defending their homeland against a genocidal war of Russian aggression. The humanitarian situation is critical and the needs immense. 100% of all donations made through this link go directly to supporting the people of Ukraine. Recently funded initiatives by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation include demining and removal of unexploded ordnance, and the evacuation of thousands of deaf people from the warzone.

Endnotes

1. The Founding of Fernie

1. Tourism Fernie, "An Overview of Fernie's History," online.

2. The Terror of the Mines

1. K.L. Buckley, Death, dying and mourning in the Crowsnest Pass: an examination of individual and community response to death and danger in the mines, 1902-1928, (Unpublished master's thesis, University of Calgary, AB. 2002), 32.

2. Buckley, 32.

3. Buckley, 33.

4. Buckley, 205.

3. The Ukrainians

1. Buckley, 200.

2. Orest Subtelny, Ukraine: A History, (University of Toronto Press, 1988), 12.

3. Alvarez-Palau, E., Díez-Minguela, A., & Martí-Henneberg, J. (2021). Railroad Integration and Uneven Development on the European Periphery, 1870–1910. Social Science History, 45(2), 261-289, online.

4. O.W. Gerus & J.E. Rea, The Ukrainiains in Canada, (Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, 1985), 5.

5. Pierre Berton, The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914, (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1984), 42.

6. Berton, 42.

4. Coming to Canada

1. Berton, 42.

5. Life Before the War

1. Ron Ulrich, "The Bastion of Victoria Avenue", Fernie Fix Magazine, (August 4, 2015), online.

2. Buckley, 31.

3. David Jay Bercuson, Alberta's Coal Industry 1919, (Edmonton: Historical Society of Alberta, 1978), 184.

4. Kassandra Luciuk, "Reinserting Radicalism: Canada's First National Internment Operations, The Ukrainian Left, and the Politics of Redress," (Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund), 11.

6. Expedient Racism

1. Berton, 4.

2. Berton, 50.

3. LaVonne Kober, "Historians of Their Own Lives: Okanagan and Settler Ukrainian Women’s Cross-Cultural Relationships during British Columbia’s Colonial and Industrial Development." (University of British Columbia Okanagan, 2010), 15.

4. Berton, 55-56.

5. Berton, 56.

6. Berton, 54.

7. Fractured Labour Movement

1. Paul Phillips, No Power Greater: A Century of Labour in BC, (Vancouver: BC Federation of Labour, 1967), 44.

2. Fernie Museum, "Fernie at War: The Morrissey Internment Camp," Exhibit Manual, (April 30, 2017), 11.

3. Fernie Museum, "Fernie at War: The Morrissey Internment Camp," 17.

3. Kassandra Luciuk, 12.

8. Where Loyalties Lie

1. Gerus & Rea, 10.

2. Lubomyr Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians, 1914-1920, (Kashtan Press, 2001), 33.

3. Lubomyr Luciuk, 30.

4. "Report of the Northwest Mounted Police: 1914," (Ottawa: Canadian Government, 1915), 109.

5. "Report of the Northwest Mounted Police: 1914," 98.

6. Lubomyr Luciuk, 30.

7. Lubomyr Luciuk, 50.

9. The War Intervenes

1. Fernie Museum, Exhibit Manual, 3.

2. Tourism Fernie Society, "The Fernie Cenotaph, Elk Valley Culture, online.

3. Buckley, 200.

4. Bohdan Kordan, No Free Man: Canada, The Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016), 99.

5. R.H. Roy & R. Foot, "Canada and the Second Battle of Ypres", The Canadian Encyclopedia, (July 26, 2006, last updated December 4, 2018), online.

6. Ann Edelstein, "Victoria's Forgotten Race Riot," Capital Daily, (June 21, 2020), online.

7. Alan Travis, "Lusitania divers warned of danger from war munitions in 1982, papers reveal," The Guardian, (May 1, 2014), online.

8. Edelstein, online.

9. Buckley, 200.

10. The Allied Miners' Revolt

1. "Against Enemy Aliens," Montreal Gazette. June 9, 1915, online.

2. "Fernie Men Firm in Refusal to Work With Aliens in Mine," Lethbridge Daily Herald, June 9, 1915, online.

3. Montreal Gazette. online.

4. "Alien Enemies at Work in Rogers Pass." Vancouver World, June 5, 1915, online.

5. Vancouver World, "A Beginning Only," June 8, 1915, online.

6. Kordan, 122.

7. Kordan, 115.

8. Fernie Museum, "Fernie at War: The Morrissey Internment Camp," 9.

9. Kordan, 101.

11. Interned at the Ice Rink

1. Fernie Museum, "Fernie at War: The Morrissey Internment Camp," 12.

2. Fernie Museum, "Fernie at War: The Morrissey Internment Camp," 15.

3. Fernie Museum, "Fernie at War: The Morrissey Internment Camp," 15.

12. The Move to Morrissey

1. Kordan, 80

2. Fernie Museum, "Fernie at War: The Morrissey Internment Camp," 16.

3. Kordan, 115.

Bibliography

Alvarez-Palau, E., Díez-Minguela, A., & Martí-Henneberg, J. (2021). Railroad Integration and Uneven Development on the European Periphery, 1870–1910. Social Science History, 45(2), 261-289. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/social-science-history/article/railroad-integration-and-uneven-development-on-the-european-periphery-18701910/1CFFBA7C4C34297FADE735F127F94DB7

Bercuson, David Jay. Alberta's Coal Industry 1919. Edmonton: Historical Society of Alberta, 1978.

Berton, Pierre. The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1984.

Buckley, K.L. Death, dying and mourning in the Crowsnest Pass: an examination of individual and community response to death and danger in the mines, 1902-1928. Unpublished master's thesis, University of Calgary, AB. 2002.

Edelstein, Ann. "Victoria's Forgotten Race Riot." Capital Daily. June 21, 2020. https://www.capitaldaily.ca/news/lusitania-victoria-german-first-world-war-riot.

Fernie Museum, "Fernie at War: The Morrissey Internment Camp," Exhibit Manual. April 30, 2017. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/PDF/Fernie%20At%20War%20Exhibit%20Manual.pdf

Gerus , O W, and J E Rea . The Ukrainians in Canada. Canadian Historical Association , 1985. https://cha-shc.ca/_uploads/5e458f5c15d09.pdf

Kober, LaVonne. "Historians of Their Own Lives: Okanagan and Settler Ukrainian Women’s Cross-Cultural Relationships during British Columbia’s Colonial and Industrial Development." University of British Columbia Okanagan, 2010.

Kordan, Bohdan. No Free Man: Canada, The Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016.

Luciuk, Lubomyr. In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians, 1914-1920. Kashtan Press, 2001.

Luciuk, Kassandra. "Reinserting Radicalism: Canada's First National Internment Operations, The Ukrainian Left, and the Politics of Redress." Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/PDF/documents/Reinserting%20Radicalism%20by%20Kassandra%20Luciuk.pdf

Phillips, Paul. No Power Greater: A Century of Labour in BC. Vancouver: BC Federation of Labour, 1967.

"Report of the Northwest Mounted Police: 1914." Ottawa: Canadian Government, 1915.

Roy, R. H. & Foot, R. "Canada and the Second Battle of Ypres." The Canadian Encyclopedia. July 26, 2006. Last updated December 4, 2018. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/battle-of-ypres.

Subtelny, Orest. Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press, 1988.

Tourism Fernie Society, "The Fernie Cenotaph, Elk Valley Culture. https://elkvalleyculture.com/stories/the-fernie-cenotaph

Travis, Alan. "Lusitania divers warned of danger from war munitions in 1982, papers reveal." The Guardian. May 1, 2014. . https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/01/lusitania-salvage-warning-munitions-1982

Ulrich, Ron. "The Bastion of Victoria Avenue." Fernie Fix Magazine. August 4, 2015. https://www.ferniefix.com/article/community/bastion-victoria-avenue

Tourism Fernie. "An Overview of Fernie's History." https://tourismfernie.com/history/an-overview-of-fernie-history

**Newspaper Articles**

"A Beginning Only." Vancouver World. June 8, 1915. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/5/1915-06-10-VW-A-Beginning-Only.pdf

"Against Enemy Aliens." Montreal Gazette. June 9, 1915. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/5/1915-06-09-MGZ-Against-Enemy-Aliens.pdf

"Alien Enemies at Work in Rogers Pass." Vancouver World, June 5, 1915. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/5/1915-06-05-VW-Alien-Enemies-at-Work-in-Rogers-Pass.pdf

"Fernie Men Firm in Refusal to Work With Aliens in Mine," Lethbridge Daily Herald, June 9, 1915. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/5/1915-06-09-LDH-Fernie-Men-Firm-in-Refusal-to-Work-With-Aliens-in-Mine.pdf