Walking Tour

The End of the Line

The Early History of Strathcona

Elyse Abma-Bouma

Library and Archives Canada 3302907

On the south bank of the North Saskatchewan River is the community of Strathcona. It resides on the traditional territory of the Sacree, or Tsu-T'ina Nation of the Blackfoot Confederacy, as well as the Strongwood Cree Nation. In the 1850s it also became home to the Papaschase Cree who were drawn to Fort Edmonton across the river. As the fur trade wound down in the 1870s, many Metis and Scottish fur traders began to settle alongside the Papaschase in what would become Strathcona. After the signing of Treaty 6 in 1877, the Papaschase were forced to relocate to a reserve in south Edmonton, though even that reserve was eventually dispersed. The Papaschase Cree have been fighting for redress ever since.

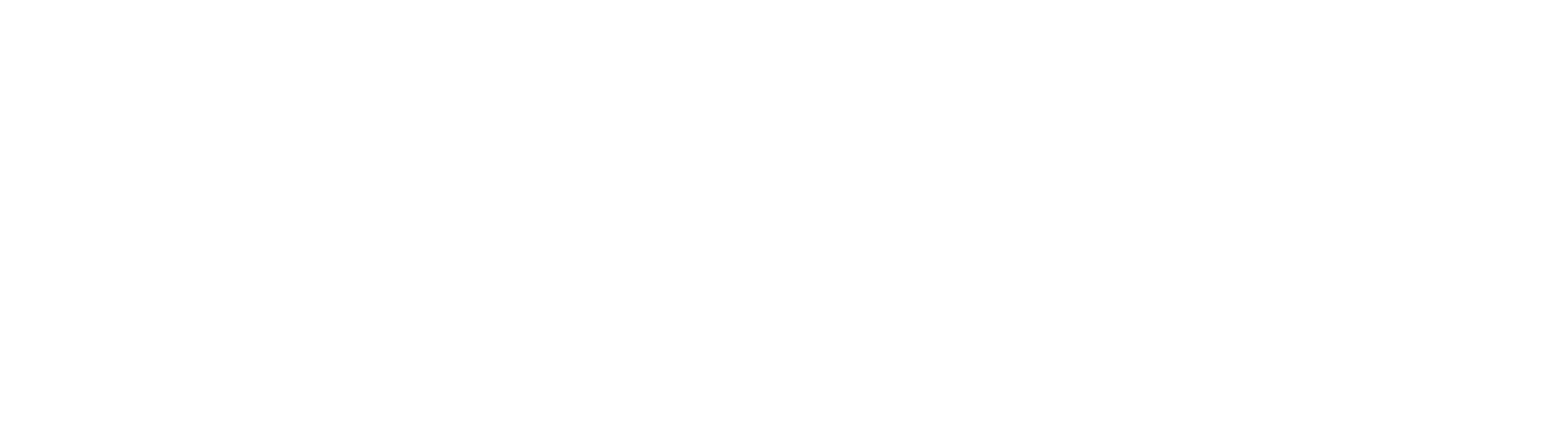

Strathcona was now fully open to European settlement, and in 1891 the Calgary and Edmonton Railway arrived and terminated here, paving the way for the growth of a town opposite Edmonton on the other side of the river. For a couple exciting decades Strathcona was a thriving commercial centre and independent municipality. When a bridge was built across the North Saskatchewan River, the obvious financial advantages of amalgamating with Edmonton were impossible to ignore, and in 1912 Strathcona became a part of her bigger neighbour to the north.

After amalgamation, Edmonton's growth surged ahead while Strathcona's slowed. For many years this was seen as a curse by Strathconians who didn't share in the wider economic prosperity. Yet it had the unintended effect of preventing the destruction of thousands of heritage buildings. This is why, wrote the historian Lawrence Herzog, "Strathcona... boasts an amazing stock of vintage buildings - a virtual time capsule of the community's early vibrant years."1

On this tour we will follow the story of Strathcona and the people who lived here. Through the built heritage we can still get a taste of the excitement people experienced during those heady years, from the Klondike gold rush, to the rapid and dynamic growth that followed Alberta's becoming a province, and beyond.

The route begins at Strathcona's old train station and follows a small circuit around the neighbourhood before returning to about the same spot.

This project is a partnership with the City of Edmonton.

1. The Railway Station

Library and Archives Canada 3302907

1913

After the local Indigenous Peoples had been evicted from this land, European settlers began to pour in. Most of them came by train, arriving at the train station you see here. Like many communities across the prairies, the arrival of the railway began a rapid growth spurt that laid their foundations. In Strathcona's case, the railway arrived in 1891, stopping near here on the south side of the North Saskatchewan River. The original terminus station was located a little north of here across Whyte Ave; this second station was built a short time after.

The railway's primary destination was the Hudson's Bay Company's (HBC) trading post at Fort Edmonton just across the river. However, it would take some time to extend the railway over that river, so it was decided for the time being to end the railway here, at the tiny township of South Edmonton, until a bridge could be built. In those intervening years, an independent community grew up around this spot; it became known as Strathcona, after Lord Strathcona, the HBC's governor at the time.

* * *

Despite Fort Edmonton's dominance in what would become known as Alberta, the CPR decided to take a much more southerly route through the province, passing by Fort Calgary, which gave that city a crucial lead in the explosive population growth that followed the railway everywhere it went. Frustrated Edmontonians had to wait another eight years for a spur line to be built north from Calgary.1

Edmonton desperately needed a railroad; The journey from Calgary to Edmonton took a week, and was by all accounts a dusty, bumpy ordeal--and especially treacherous in the long winters. The geographic challenges that Albertans face today were magnified many times over in those days. Depending on the season, travellers on the remote highway could get trapped in seemingly bottomless morasses of mud, caught in white-out blizzards, or be parched with thirst under the relentless summer sun.

The spur line would reduce the journey to Calgary to a single day, and allow people, supplies, and--of course--economic activity to flood into Edmonton. On March 28, 1891, the Edmonton Bulletin mourned the slow economy but noted that "with the opening of the railroad work in the spring there is no doubt that [goods] will be in good demand."2 Though Edmonton had much to offer, lack of transportation made exporting the potatoes, flour, and other goods produced here extremely inconvenient.

The CPR was a profit making endeavour and they were ruthless in their desire to build the railway in a manner that was both cheap and sure to net them a tidy profit. Building a bridge over the North Saskatchewan River was sure to be expensive, and it just so happened the CPR owned most of the land on the south side of the river--that is, modern Strathcona. So it was decided that the officially named Calgary and Edmonton Railway would in reality be the Calgary and Strathcona, with the line terminating here on the south side of the river. That way the CPR could avoid the cost of a bridge and recoup some of their expenses by selling all the rural farmland around the new station, which they correctly predicted would become a town in its own right.

Edmontonians who still had to ferry across the river to the new station were thrilled anyhow. When the railway finally opened to Strathcona it was a joyous occasion. Edmonton began to grow, reaching a population of 1,500 by 1897.3 Strathcona, as home to the train station, also grew to accommodate CPR employees and travellers, reaching 1,000 by 1899.4

2. Launchpad to the Klondike

Provincial Archives of Alberta IR323

1910s

Further north than any major city in North America, Edmonton has long been the jumping off point for expeditions to the Arctic. That is why it's often called the 'Gateway to the North'. The most memorable of those expeditions being the Klondike Gold Rush of 1896-99.

As the northernmost point that could be reached by railway, Strathcona was where thousands of prospectors from every corner of the globe converged to begin the most difficult portion of their long trek to the Yukon by horseback or on foot. In those exciting times Strathcona was filled with brave souls preparing for the ordeal that lay ahead; purchasing supplies, swapping stories over beer, and getting a last night's sleep in a warm, dry hotel room. The prominent old building you see here, the Strathcona Hotel, was one such hotel.

* * *

When news of the latest--and one of the greatest--gold finds filtered out of the Yukon in August 1896, there was no shortage of takers. Few had any conception of the remoteness of the Yukon, and few cared. They flocked from every continent to Canada, and from there, many rode the railway to the very last stop to the north: Strathcona.

"Latest news from the Yukon," the Edmonton Bulletin wrote in 1897 "confirms the wildest reports that have been circulated as to the richness of the Klondike gold fields; but with that news comes the stories of shortage of food and the information that transport of supplies has ceased for the season."3

Many gold hunters would read the first part of that dispatch and ignore the second. Over the next couple years, Strathcona's streets filled with adventurers preparing to make their way north. The North West Mounted Police (forerunner of the RCMP) were appalled at the hordes of ill-prepared and inexperienced miners eagerly rushing to the Yukon's inhospitable Arctic environment. They enforced regulations ensuring that everyone leaving Strathcona must do so with a sufficient quantity of supplies survive the 2,000 kilometre journey.

This meant that many of the estimated 25,000 miners who departed Strathcona had to buy all of their supplies here, and hotels and general stores sprang up all over the community servicing the prospectors as they prepared for the arduous journey.1 This was a welcome shot in the arm to a local economy that had been languishing through the global depression of the 1890s.4

Few of those afflicted with gold fever would ever find what they were looking for in the Yukon. Most would spend their savings simply reaching the place and many died during the journey to the Klondike. The Gold Rush left a lasting legacy here: While Edmonton had been a long-time destination for fur traders, Strathcona cemented the area's reputation as the 'Gateway to the North'. 5

3. The Farmers

1913

The turn of the last century brought more than those afflicted by gold fever to Strathcona. In the years following the Klondike Gold Rush, the trickle of settlers into this region swelled to a torrent as the federal government worked tirelessly to encourage immigrants from Britain, eastern Canada, the United States, and increasingly, Eastern Europe to settle the prairies. It just so happened that Alberta contained some of the best farmland on earth, and the government wished to build a strong agrarian economy here.

It was on this spot on Whyte Avenue that farmers would come from the surrounding areas to trade livestock, and in this photo you can see a group of men gathering to discuss the fate of a number of horses. In the distance you can see the Strathcona Hotel we saw in the last stop.

* * *

The fastest way to do this was to lure prospective immigrants with promises of 160 acres of land with only on catch: the immigrant had to build their own house (usually out of sod or rough-hewn logs) and successfully farm the land for three years. This was called homesteading, and if you made it to three years, the land was yours.

Now try to imagine doing this yourself. Do you know how to build a sod house with your bare hands? Do you know how to farm 160 acres of prairie by hand? Well, it turns out a lot of the new immigrants didn't know either.

In the 1890s, the racist attitudes of the time were strongly reflected in immigration policy, and the Canadian government had long held a strong preference towards British settlers, who they saw as the world's top racial 'stock'. However, many of the British immigrants that arrived on the prairies to homestead early on came from factory cities, and knew about as much about farming as you or I (unless of course you know a lot about farming, in which case we apologize). In much of Alberta, only a small proportion of the original homesteaders were able to stick it out three years. As word got back to Britain about the caveats to the free land offer, fewer and fewer of these amateur farmers were willing to make the trip.

So if many of these British immigrants weren't a good match for Alberta's conditions, where would these millions of farmers come from? At the time people from eastern Europe were seen by much of the Canadian public as coming from a racially inferior 'stock', but unlike rapidly industrializing Britain, many of these eastern Europeans were still peasant farmers. And many of them wanted to leave.

Laurier's Minister of the Interior, Clifford Sifton, was a bold and energetic man. He believed that the people of eastern Europe were perfectly suited to turn Canada's prairies into the breadbasket of the world. In a 1901 memorandum he wrote "Our desire is to promote the immigration of farmers and farm labourers. We have not been disposed to exclude foreigners of any nationality who seemed likely to become successful agriculturalists."1 He championed an immigration policy that would in the space of a decade bring over a million people, including hundreds of thousands of eastern Europeans, into the prairies.

At the time this was a hugely controversial move, especially in eastern Canada. Many were outraged that the government was allowing Russians, Ukrainians, Hungarians, Romanians, and Poles, along with religious minorities in those countries like the Mennonites and Doukhobors, to settle in Canada. Would they dilute the national culture? Would they ever integrate?

Yet ever-practical Albertans immediately warmed to the new arrivals: they were not only effective farmers, but helpful neighbours. A Lethbridge newspaper wrote of them:

"This class of immigration is of a top-notch order and every true Canadian should be proud to see it and encourage it. Thus shall our vast tracts of God's bountifulness…be peopled by an intelligent progressive race of our own kind, who will readily be developed into permanent, patriotic solid citizens who will adhere to one flag."2

The government's new openness only extended so far as eastern Europe, and racist policies continued to bar entry to people of colour. Asian people were largely prevented from fulfilling the government's immigration goals by head taxes charged on new immigrants. Though many Chinese wished to homestead, they were unable to.3

In the end, Sifton was able to bring over a million immigrants into Canada in a decade, immigration on a scale which has been rarely seen in recorded history. Sir Wilfrid Laurier declared in a 1904 speech that "the 20th century shall be the century of Canada and Canadian development".4 The rapid growth of Strathcona was an important part of that optimism.

On a grand scale, the growth of Strathcona in the 1900s was an important component in a trend of world-historic importance. The opening up of the Canadian prairies was part of a titanic global development that opened up not just Canada's west to agriculture, but also that of the United States.5

Taken as a whole, this development was the largest and most rapid increase in the amount of arable land in the history of the human race. It changed things practically everywhere. Alberta, along with the rest of western North America, became the world's breadbasket, and directly contributed to population increases across much of the globe. The ripples sent out by the growth of Strathcona and the farms around it have reverberated around the world ever since.6

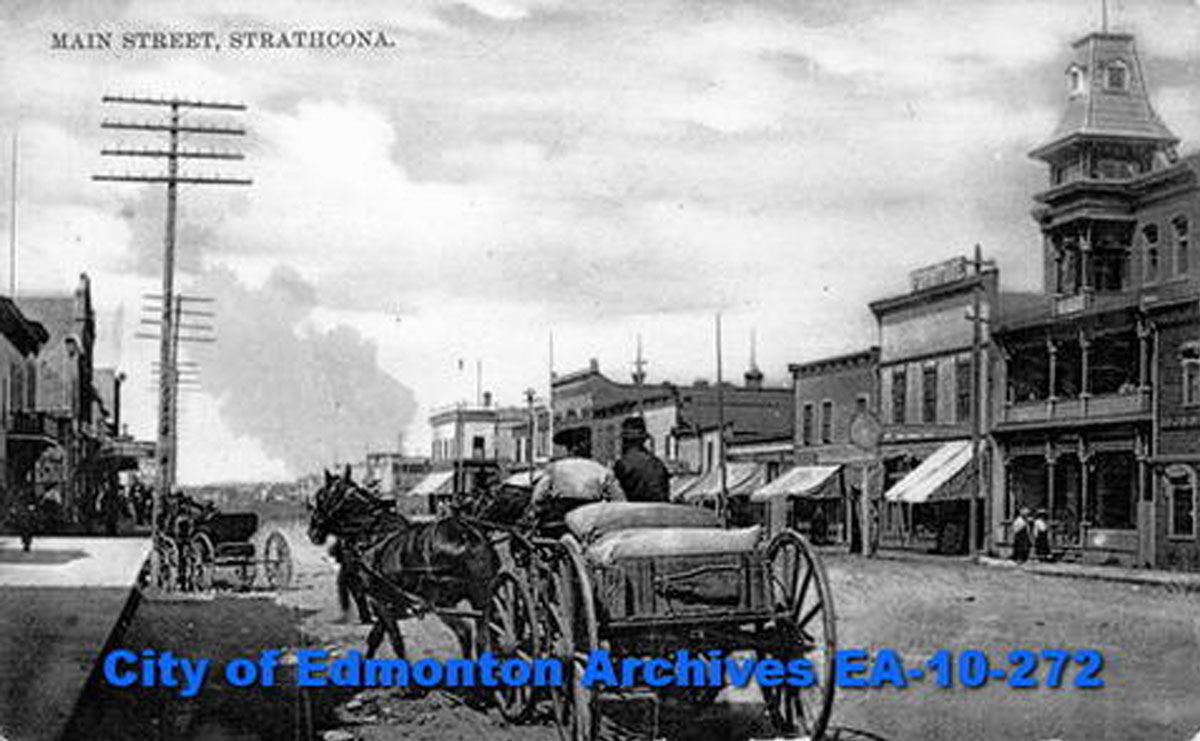

4. Life in Strathcona

1903

In front of you is the Strathcona Hotel, which was built near the railway station to accommodate travellers when they reached the end of the line. It's located on Whyte Avenue, which was named after the regional CPR director, William Whyte. The hotel is the oldest surviving building in Strathcona.1

In the 1890s, after the arrival of the railway, Strathcona saw a small immigration boom. Most of the new arrivals wanted to farm or work for the railway, but there were also a number who came to start small businesses that could provide goods for those farmers. That latter group mostly set up shop on Whyte Ave. As Whyte Ave became a service centre for the surrounding countryside, many rough wooden shops went up to meet the needs of their customers. The dirt roads and wagons made this place a loud and dusty base for travellers making their way to Fort Edmonton, or points further north.

* * *

As with most small prairie settlements, pioneer life was an ongoing challenge. A bad harvest or failed quest for gold or coal could dissolve a community just as quickly as a good harvest or gold strike could build one. Dramatic weather changes meant that streets turned from dust to mud and back again in the span of a single day. Shopkeepers were thwarted by lack of shipments due to poor transportation and often did not have enough inventory to supply every adventurer that passed through on their way to the Klondike. Farmers toiled away in the surrounding fields, ploughing the land and caring for the animals that provided their livelihoods. Seasonal labourers, who often stayed in this hotel for months at a time in the off-season, hauled bricks and timber through snow, heat, and rain.2

While men had most of the paid jobs, the Western economy depended on the unpaid domestic labour of women and children. Women might sometimes be paid a small wage for dressmaking or laundering clothes, but it was widely understood that a woman's role was to cook for her family, raise her children, and undertake the seemingly endless list of miscellaneous tasks involved in managing a household. Hiring young children was common practice in small prairie towns as well, as there were no laws prohibiting child labour.3

5. Edmonton and Strathcona

Provincial Archives of Alberta A9841

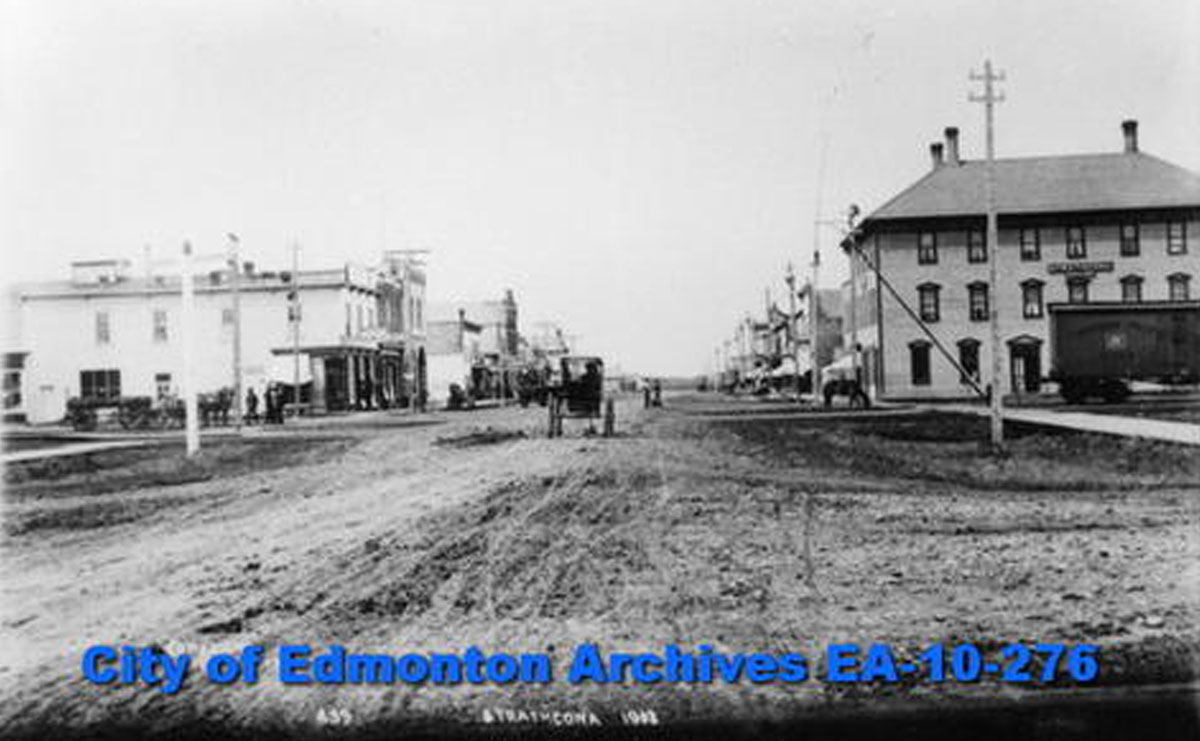

1909

This photo shows a small crowd, including a lot of children, gathering to watch a marching band tramp down Whyte Ave. You'll notice an early car just to the right of the band, in front of the Windsor Hotel. These would become a much more common sight on Edmonton's streets in the years to follow.

This photo was taken a couple years after Strathcona had officially incorporated as a city (1907), which was a few years before Strathcona became a part of Edmonton (1912), and is a reminder of the civic pride people felt in the growing community; ultimate amalgamation with Edmonton was not a painless process.

* * *

Residents of Strathcona bristled at the suggestion they were merely a southern appendage to Edmonton. Soon a rivalry began to develop between the two communities facing off across the river. Nevertheless, Strathcona was never really in a position to compete. Edmonton was Edmonton after all. Her population was much larger, Jasper Avenue's economy was much more prosperous, and most importantly, in 1905 she had been declared the capital of the new province.

By 1907, even as Strathcona was able to declare herself a city in her own right, she increasingly found herself squeezed between Edmonton to the north and the growing community of Leduc in the south. With its comparatively small tax base, Strathcona's government struggled to provide the amenities people in an early 20th Century city had come to expect. In the years since Edmonton's designation as capital, that city's population growth had shot past Strathcona's. By 1911 her population was four times larger than Strathcona's 5,600. If Strathcona could amalgamate with Edmonton it would open up access to a vastly larger tax base--and the modern amenities that came with it.

In 1911, a referendum was held on whether Strathcona should become a part of Edmonton. The benefits included lower property taxes, improved transit, and a functioning police force, as well as city council representation in Edmonton City Hall. The result was overwhelming: 667 for and 97 against. On February 1, 1912, Strathcona officially became South Edmonton, a part of Edmonton.

There were zealous Strathconians who found this a bitter pill to swallow. One resident, John Carmichael, was always against amalgamation. His granddaughter still remembers how much the town meant to him:

"There was a quite a bit of animosity against some of the businessmen on the north side in Edmonton. Until the day he died, he always said he would live in Strathcona, not South Edmonton."1

In addition, many of the promised benefits of amalgamation failed to materialize. Taxes did not subside, instead they increased to help pay for the new parliament buildings as well as the High Level Bridge. It is estimated it cost every man, woman, and child in Edmonton-Strathcona $100 (equal to about $2,200 today). The new bridge and streetcar service did deliver the promised new transit by making it easier to access downtown Edmonton, but this was a double-edged sword, as Jasper Avenue's cheaper stores drew business away from Whyte Avenue.2

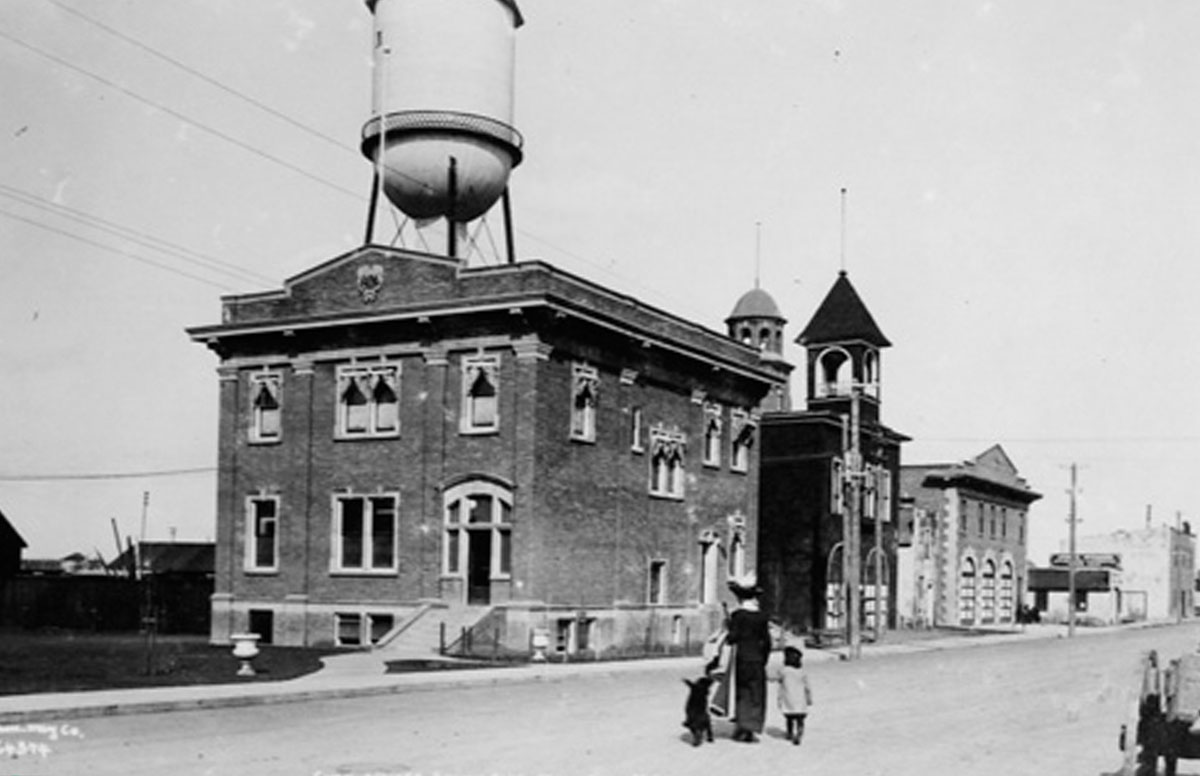

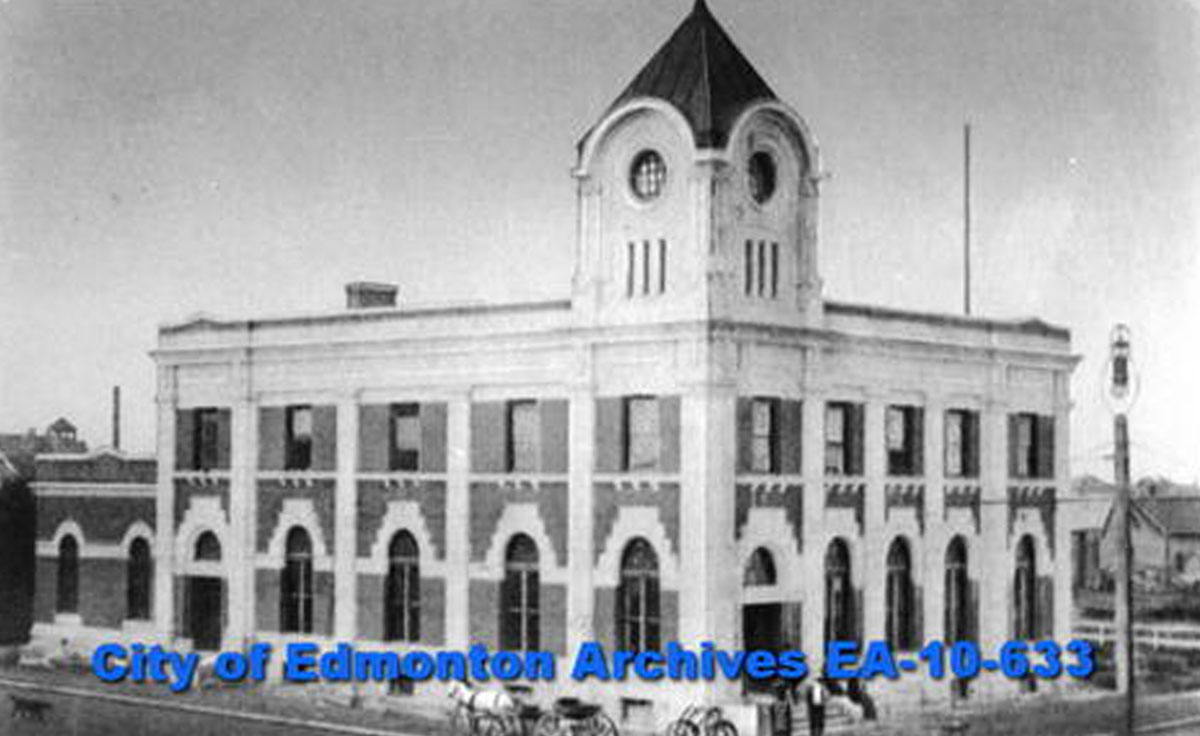

6. Fire Hall No. 1

1920

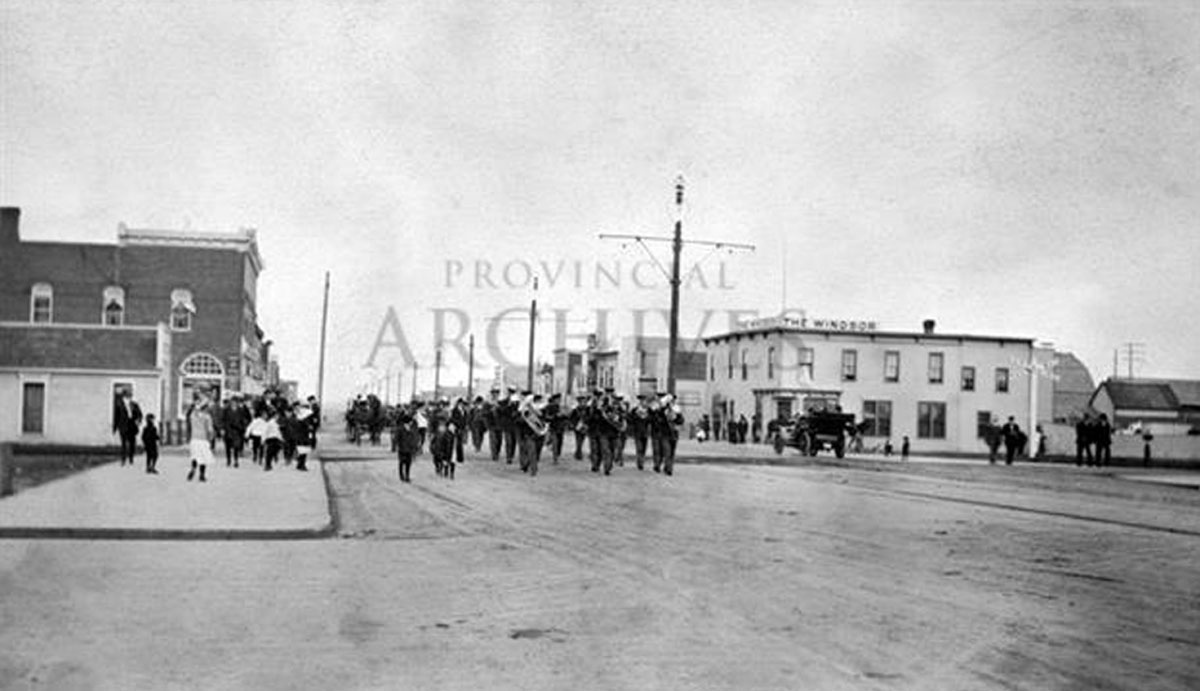

Completed in 1910, Strathcona Fire Hall No. 1 is the oldest major fire hall in Alberta. Though modern fire trucks have outgrown the building, we can still see the large doors that once housed Strathcona's cutting-edge horse-drawn fire engines. When Edmonton and Strathcona combined, Firehall No. 1 became Firehall No. 6 and continued to serve the district of Strathcona until the 1950s.1

* * *

Strathcona initially had a volunteer fire station on this site.2 When Strathcona incorporated as a city in 1907, the new city council decided Strathcona should have a more permanent and fireproof character. As one of their first regulations, they deemed all new public buildings had to be made of brick or stone. Nevertheless, that didn't account for most of the old wooden buildings, such as the water tower that used to stand behind the volunteer fire hall. In 1909, the Strathcona Chronicle reported:

"The fire which started shortly after noon yesterday in the water tower completely destroyed the wood casting of the tower from the bottom to the top and left nothing but a blackened skeleton of the iron work of the tower."3

By 1910, it was decided a real brick fire hall was necessary, and the result was Strathcona Fire Hall No. 1 in front of you. Once amalgamation occurred it was demoted to Edmonton Fire Hall No. 6 and fulfilled its role until 1954, when it became a storage building. Finally, in 1974, it was purchased by the Walterdale Theatre Group and became a playhouse, a purpose it has served ever since.

7. The Orange Order

Glenbow Archives NA-1328-64374

1912

This spot has been home to many different structures, events, and histories. At one point it was home to the Strathcona Water Tower, along with some of its public buildings; today it has a thriving theatre and lovely farmers market. Despite all of this change, one building still stands as it once was--you can see the edge of it on the very far left of this photo: the Orange Hall.

The Orange Hall was built in 1903 for the Orange Order, a religious-fraternal organization created in England to unite Protestants opposed to Catholicism. It was especially forthright in issues regarding the religious dominance of Ireland. In Canada, the Order became very influential in municipal politics.1

* * *

Many political leaders, including Canada's first Prime Minister, John A. MacDonald, have belonged to the Orange Order.2 During the Red River Rebellion, one of their own was executed and the Orange Order were quick to support the Prime Minister's mission to bring down Louis Riel and the subsequent North-West Rebellion.

A feature in the "Saturday News" (1907) featuring "Alberta's Chief Magistrates" noted Strathcona's own Mayor N.D. Mills as the "elected Grand Master of the Orange Order of the North-west Territories."3

This hall was built in 1903 by the Orangemen, who were mostly craftsmen, and to reduce the cost they used materials readily available in Strathcona. The simple wooden frame isn’t any revolution in architecture, but it served its purpose well: it provided a vital meeting space for Strathconians, helped promote the community, provided social assistance, and promoted Orange interests, such as Protestant unity. They also held social events, which made the harsh winters more bearable, and they helped residents through difficult times.4

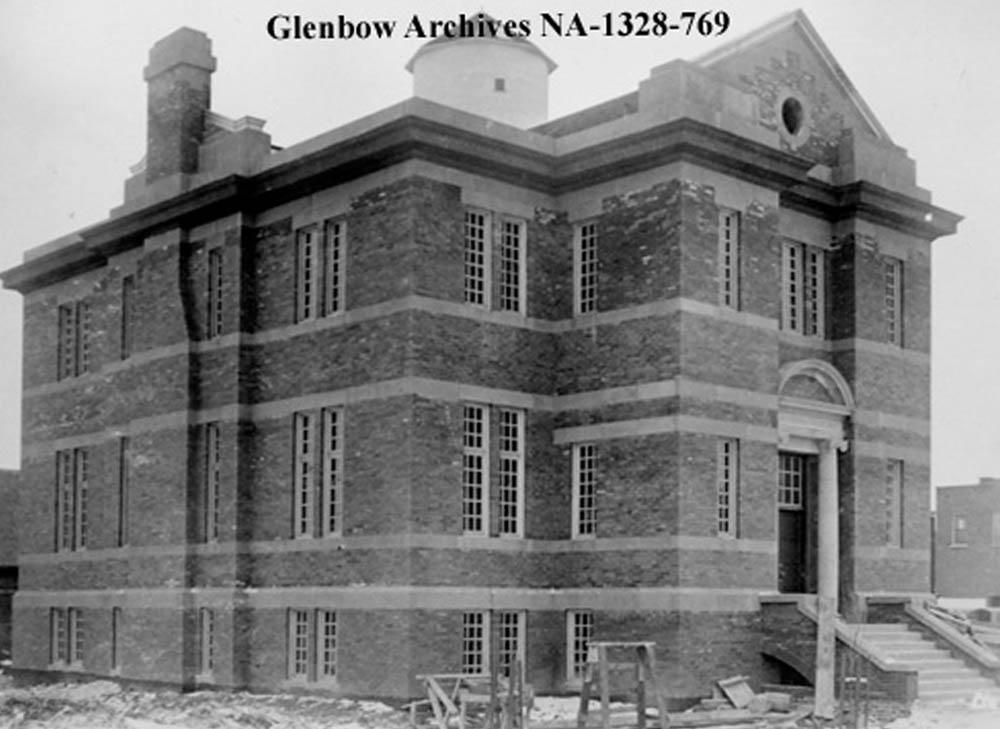

8. The Old Strathcona Library

1913

This is Strathcona's public library, the first library in Edmonton and one of the oldest in Alberta. It was built following amalgamation with Edmonton in 1912 and became a community centre in addition to being a repository for knowledge. As one of the premier public buildings in Strathcona, it was intended to have an impressive and imposing aspect, which you can see in its English Renaissance style facade today. It continues to serve its original function, and remains one of the busiest libraries in the province.

* * *

In the early 1900s construction of public libraries across Canada and much of the rest of the rest of the English-speaking world was funded by the Scottish-American steel magnate, Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie grants in Canada gave nearly every city in Canada an opportunity to have a library.1

In 1907 Strathconians were offered such a grant by Carnegie, but the Strathcona council evaluated the offer and decided the funding wasn't enough to build a library befitting the forward-looking city. For five years the library went unbuilt, as the council worked to raise the necessary funds. Finally, it became apparent that one of the benefits of amalgamating with Edmonton would mean that the City of Edmonton would be able to fill the funding gap. After Strathcona became part of Edmonton, the gap was filled and construction of the library began.2 3

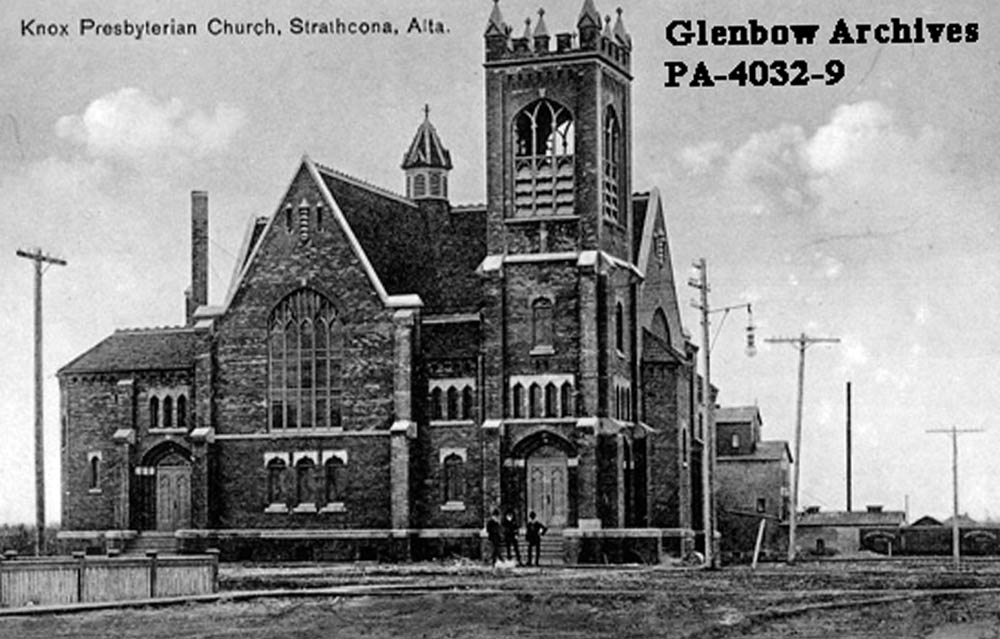

9. Religious Life

1910

As immigration to Edmonton increased with the railroad, so did the need for churches. The Knox Presbyterian Church was completed in 1907 and is still in use today. Christianity was a hugely important part of Canadian life in the early twentieth century, and buildings like this played a variety of roles in the community. The large number of churches built in Strathcona is an indicator of the piety of the people who lived here, shows just how many different Christian denominations made this place their home, and hints at how much wealth they had to fund such buildings.1

* * *

Father Lacombe was a prominent missionary in the Canadian prairies, and was revered by many early Edmonton residents. Katherine Hughes wrote this about him in 1911:

"At the outset he appears as a knight-errant on the western Plains — a picturesque figure with the Red Cross of his flag floating above him, here, there and everywhere along the prairies between the Red River and the Mountains of the Setting Sun... now sharing the tepees of the nomad tribes; now making a stand at some mission-place — with axe and plough guiding the Metis and Indian to the ways of the white man . . . leading them out from the blanket and tepee to the school and homestead."2

Though the Indigenous people of the prairies had their own complex cosmologies and systems of belief, many European settlers fervently believed it was their mission to convert them to Christianity and erase those beliefs. This would have lasting catastrophic consequences for Indigenous communities, as we can plainly see with the legacy of cultural genocide in residential schools that haunts Canada today.

For those who were not missionaries, religion was the common ground on which settlers could build communities in the prairies. In its early days, Strathcona had a large Scottish population so Presbyterian church attendance was particularly high. As more settlers came to the Edmonton area, more denominations began to pop up including a Catholic parish set up by Father Lacombe himself.

The Knox Church in front of us was built in a style typical of turn-of-the-century Presbyterian churches and has housed many different Protestant denominations throughout the years. The many churches in the Strathcona area shows the massive church attendance in the beginning of the 1900s and speaks to the strong religious beliefs held by the people who settled the prairies.3 4

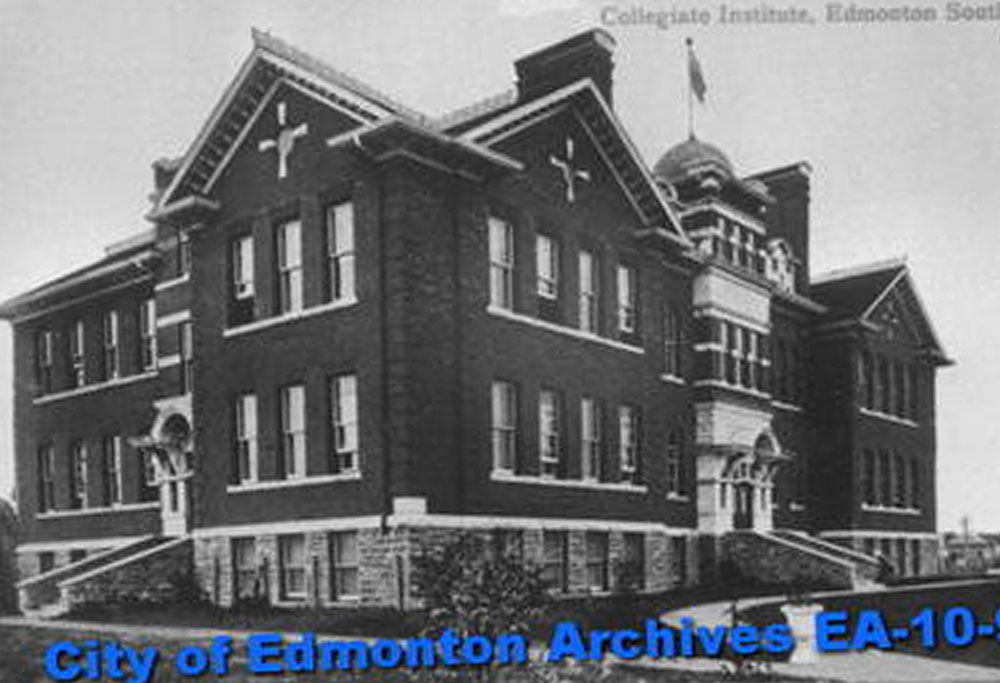

10. Strathcona Collegiate High

1909

Here in 1908 one of the first high schools in Alberta opened: the Strathcona Collegiate High School. The school educated students in both the liberal arts and sciences, beginning to develop the school and the nearby University of Alberta's reputation as the 'university city.'

* * *

Strathcona students who attended this high school would add onto their previous education by learning subjects such as rhetoric, constitutional and industrial history, trigonometry, and could choose to learn two foreign languages such as German, Latin, or French.1

In addition to the high school, Strathcona was home to Alberta’s first university - the University of Alberta. It was similar to other Canadian universities with one stark difference: university president Henry Marshall Tory drafted the University Act which only allowed courses that afforded women the same educational opportunities as men.2

Alberta's education system sought to shape citizens of good character by teaching basic skills in one room school houses across the prairies. Prior to the First World War, Strathcona housed most of Alberta’s higher education, making it an attractive addition to Edmonton. Strathcona Collegiate High School was built in the Edwardian Classical Free architectural style, the cornerstone was laid by premier Alexander Rutherford, and the school was home to university president Tory's first office. 3

11. The Postal Service

1914

The Strathcona Post Office was constructed in 1913. Here, residents of Strathcona would come to check for letters from relatives in the rest of Canada and around the world, and send news back home. Businessmen would send off contracts, and local shops could pick up inventory, and prairie farmers could send off order lists of equipment and household goods they picked out of mail order catalogues.1

* * *

Initially, messages were transported through Canada by messengers who were usually Indigenous people. They were hired on an individual basis by companies such as the Hudson's Bay Co. to carry letters between trading posts and forts.

By the mid-1700s, the British Colonies had a semblance of a postal system with two appointed postmasters general tasked with ensuring the punctual delivery of the mail. During this time, it could take upwards of four months for a letter to make its way from Montreal to Halifax let alone from Montreal to Strathcona.

As the railroad reached further westward, the prairies benefitted from more frequent mail service. By the time the railway had made its way North from Calgary, Strathcona was thrilled to have such prompt delivery and receiving mail within weeks rather than months.

In 1868, the mail service started to be run by the federal government, leading to many new jobs in the postal service. On this spot, postal workers made certain that Strathconians received their important documents, letters, and packages from far and wide.2

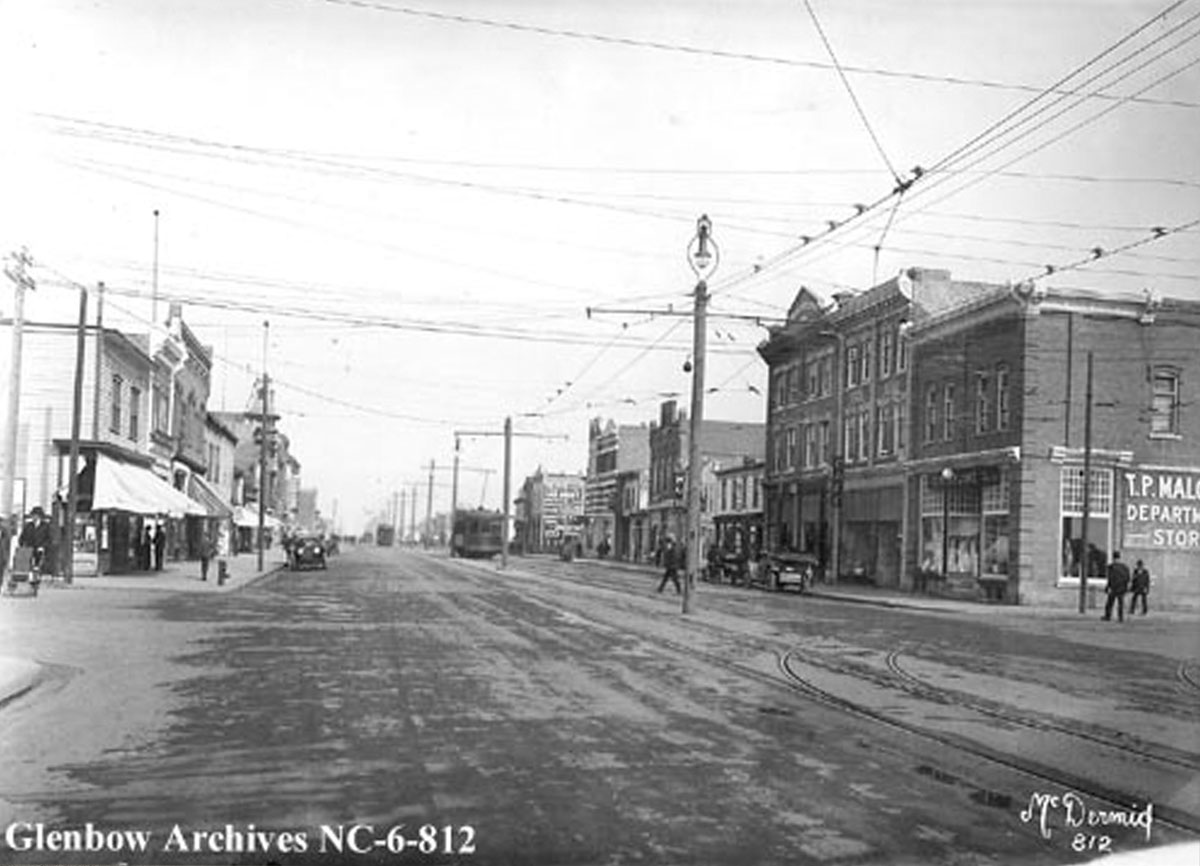

12. The Streetcar

1914

Looking west down Whyte Avenue, the historic photo shows the streetcar lines that once ran down the road. With the completion of the High Level Bridge in 1913, streetcars became an effective and economic means of transportation from Strathcona to Edmonton. Although these streetcars ran largely accident-free, other cities experienced difficulties with the transit system that were sometimes fatal. As a result, the Edmonton Radial Railway was shut down in 1951 to avoid accidents in Edmonton.

* * *

On its face, the streetcar seemed like a perfect form of transport for Canadian cities, but it had its flaws: In Victoria, B.C. a streetcar overloaded with 143 men, women, and children was crossing a bridge when a lack of safety standards caused the car to plunge into the river killing 55 people. A resident of Victoria wrote:

"Very bright sunshine – but a day of mourning – four divers still engaged in the endeavour to recover the bodies from the wreck of yesterday – vast crowds surround the fatal spot – boat launches steamers and a large derick [sic] constantly at work. 49 bodies taken out up to the present."2

In Edmonton, the Radial Railway caused few issues outside of the tracks having to be cleared of snow in the winter. To avoid accidents, Edmonton and Strathcona had coloured glass lights put in to make the cars visible:

"The interurban streetcars have now a distinguishing mark by which they can easily be recognized on the streets both at night and in the day time. In addition to the signs 'Strathcona' and 'Edmonton' at either end of the car red glass has been put in the center of the transom or roof at each end with small pieces of white on each side."3

The street car provided opportunities for Canadian cities, such as Edmonton in the twentieth century, to implement an affordable form of public transportation. The first system of its kind for Canada, the streetcar led to more innovative infrastructure and implementation of traffic and vehicle safety laws.

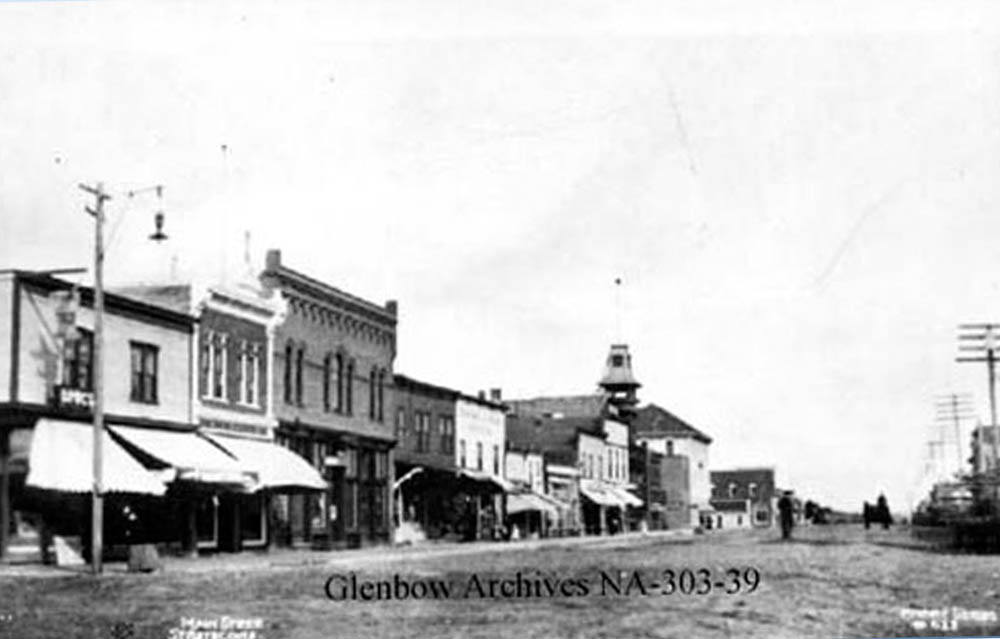

13. Strathcona Expands

1906

Looking east down Whyte Ave at the centre of Strathcona, we can see the busy avenue filled with shops and hotels just as it was in 1906. Although parts of Strathcona look much the same due to preservation efforts in the 1970s, Strathcona was a city of frequent change and rapid growth.

* * *

In Strathcona, where land was relatively plentiful and services available, the population boomed from 50,000 to 75,000 in just the two years before World War I. Population dropped back down to 50,000 shortly before the war began causing Strathcona to become known as a community that thrived prior to the First World War.

Strathcona experienced a great deal of turmoil after the decision to amalgamate. According to the Edmonton Bulletin: "Edmonton and Strathcona will formally unite their destiny—No celebration of the event."1

Amalgamation was a feeling of defeat for Strathcona, but the promise of lowered taxes and opportunity offered by Edmonton was an offer too good to pass up for the little city on the south side of the river. Amalgamation shifted Strathcona and it became more residential, many Strathconians would go to Edmonton to purchase goods as it was cheaper and Strathcona businesses suffered as a result.

However, the railway station was still in Strathcona, so all travellers had to pass through on their way to Edmonton. Though the two years after amalgamation caused an upset, Strathcona remained resilient and changed to accommodate the new environment. It was around this time that the famed Princess Theatre was built, drawing Edmontonians to the south side for entertainment and leisure time.2

When World War One began in late 1914, Strathcona's population dropped back to 50,000. The real estate boom had ended with the completion of the High Level Bridge and Legislature. War was upon them and everyone knew that it was going to come at a high cost.

"At a conservative estimate the present war will cost a million lives. It may cost more than double that if it stretches out into a number of years and involves other nations… Those dead leave behind countless dependents whose maintenance inevitably falls upon the country in one form or another… who triumphs in this war? And who wins the next?"3

14. Booming Business

Provincial Archives of Alberta A6753

1902

This spot was once home to the A.C. Baalim Fruiterer and Confectioner. The original buildings are no more, as they were victims of fire, and new structures took their place. Like much of Whyte Avenue, businesses come and go and buildings from the golden age of Strathcona now serve a different purpose than they once did. However, this heritage site still remains one of the busiest parts of Edmonton, hosting festivals and local artisans.

* * *

Whyte Ave has always been home to a diverse collection of shops and accommodations. A 'Home and Society' article in the Edmonton 'Saturday News' read:

"Landed in the bus I am out of breath, but now when I look Strathconawards I shall watch with an added interest for new landmarks against the skyline, and get to wondering what on earth that baby sister is up to next."1

15. Strathcona Hotel

1900

Looking west, we can see the Dominion Hotel which still stands, thanks to preservation efforts in the 1970s. The efforts began the process by which Old Strathcona would come to be the heritage site it is today. Now transformed into an artistic centre with many performance venues and shops, the once small town has changed to accommodate a new time.

* * *

Endnotes

- 1. Edmonton Historical Board, "Strathcona," online.

1. The Railway Station

1. Kenneth W. Tingley, Allan Shute, and Lawrence Herzog, Building a Legacy: Edmonton's Architectural History, (Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada: Coteau Books, 2012).

2. The Edmonton Bulletin, March 28, 1891. Online.

3. City of Edmonton, "Population History," City of Edmonton, 2016. Online.

4. "Strathcona Collegiate Institute," Alberta Register of Historic Places, 2019. Online.

2. Launchpad to the Klondike

1. Kenneth W. Tingley, Allan Shute, and Lawrence Herzog, Building a Legacy: Edmonton's Architectural History (Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada: Coteau Books, 2012), 18-23

2.Pierre Berton, "Pierre Berton on the Klondike Gold Rush," The Canadian Encyclopedia, March 6, 2002. Online.

3. The Edmonton Bulletin. October 7, 1897. 2.

4. Gates, Michael, "Klondike Gold Rush". The Canadian Encyclopedia. July 19, 2009. Online.

5. Bob Hesketh and Frances Swyripa, Edmonton: The Life of a City (Edmonton: NeWest, 1995), 58-69.

3. The Farmers

1. Valerie Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy: 1540-1990 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1997), 84-104.

2.Knowles, 90.

3. Erica Gagnon, "Settling the West: Immigration to the Prairies from 1867 to 1914," Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21. Online.

4. Wilfrid Laurier, "Wilfrid Laurier: Let Them Become Canadians, 1905," The Canadian Encyclopedia, July 13, 2017. Online.

5. Jane McCracken, "Homesteading," The Canadian Encyclopedia, February 10, 2009. Online.

6. Jurgen Osterhammel, The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century, (Princeton University Press, 2014), 213.

4. Life in Strathcona

1. Tom Monto, Old Strathcona, Edmonton's Southside Roots (Edmonton: Crang Publishing, 2011), 120-22.

2. "Urban Settlement," Edmonton Maps Heritage. Online.

3. Sarah Carter, Imperial Plots: Women, Land, and the Spadework of British Colonialism on the Canadian Prairies (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2016).

5. Edmonton and Strathcona

1. Gordon Kent, "100 Years of Amalgamation; Originally a Separate Community, Bustling Strathcona Was Absorbed by City on Feb. 1, 1912," Edmonton Journal, January 30, 2012. Online.

2. Hesketh and Swyripa.

3. Kent, online.

6. Fire Hall No. 1

1. D. Leonard, "Strathcona Fire Hall No. 1," Alberta Register of Historic Places, February 2006. Online.

2. Leonard, "Strathcona Fire Hall No. 1," online.

3. Strathcona Chronicle, January 22, 1909, 5. Peel's Prairie Provinces, University of Alberta Libraries.

7. The Orange Order

1. Kevin Plummer. "Historicist: Orangemen and The Glorious Twelfth of July." Torontoist, 15 August 2011. Online.

2. Michael Wilcox. "Orange Order in Canada." The Canadian Encyclopedia, 6 June 2007. Online.

3. Saturday News, January 12, 1907, Page 1. Peel's Prairie Provinces, University of Alberta Libraries. Online.

4. Parks Canada, "Loyal Orange Hall #1654 of Edmonton," HistoricPlaces.ca. May 2005. Online.

8. The Old Strathcona Library

1. Margaret Beckman et al. "Libraries." The Canadian Encyclopedia. 7 Feb. 2006. Online.

2. Alberta Register of Historic Places, "Strathcona Public Library." 2015. Online.

3. Todd Babiak. Just Getting Started: Edmonton Public Library's First 100 Years, 1913-2013 (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2013).

9. Religious Life

1. D. Leonard. "Knox (Presbyterian) Church." Alberta Register of Historic Places, Nov. 2005. Online.

2. Kathleen Hughes. Father Lacombe: The Black-Robe Voyageur. (William Briggs Publishing, 1911), 2.

3. John Webster Grant. "Religion and the Quest for National Identity: The Background in Canadian History." Religion and Culture in Canada, Canadian Corporation for Studies in Religion, (1977), 7–22.

4. Connor J. Thompson, "Bricks, Faith, Community: A History of Edmonton Christianity to 1929," Alberta History, Spring 2018.

10. Strathcona Collegiate High

1. Amy Von Heyking, "Schooling for "Good Character," 1905-1920," in Creating Citizens: History and Identity in Alberta's Schools, 1905-1980 (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2006), 7-29.

2. Rod Macleod, "University of Alberta," The Canadian Encyclopedia. 14 Feb. 2013. Online.

3. Alberta Register of Historic Places, "Strathcona Collegiate Institute," 2015. Online.

11. The Postal Service

1. Kenneth W. Tingley, Allan Shute, and Lawrence Herzog, Building a Legacy: Edmonton's Architectural History (Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada: Coteau Books, 2012), 51.

2. Mark Anderako and H. Griffin, "Postal System," The Canadian Encyclopedia, 15 Dec. 2012. Online.

12. The Streetcar

1. Brian E. Sullivan, "Streetcars" The Canadian Encyclopedia. 5 Feb. 2015. Online. www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/.

2. Point Ellice House Museum and Gardens, "Point Ellice Bridge Disaster," 2019. Online.

3. The Edmonton Bulletin, December 23, 1908, Peel's Prairie Provinces, University of Alberta Libraries, 2. Online.

13. Strathcona Expands

1. The Edmonton Bulletin, February 1, 1912 (Morning Edition), Page 2. Peel's Prairie Provinces, University of Alberta Libraries. Online.

2. Hesketh and Swyripa.

3. The Edmonton Capital, September 22, 1914 (Special Mail Edition), Page 4. Peel's Prairie Provinces, University of Alberta Libraries. Online.

14. Booming Business

1. Saturday News, November 30, 1907, Page 10. Peel's Prairie Provinces, University of Alberta Libraries. Online.

Bibliography

Alberta Register of Historic Places. "Strathcona Collegiate Institute," 2019. https://hermis.alberta.ca/

Alberta Register of Historic Places. "Strathcona Public Library." 2015. www.hermis.alberta.ca/

Anderako, Mark and Griffin, H. "Postal System," The Canadian Encyclopedia. 15 Dec. 2012. www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/

Babiak, Todd. Just Getting Started: Edmonton Public Library's First 100 Years, 1913-2013. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2013.

Beckman, Margaret et al. "Libraries." The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, 7 Feb. 2006. www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/

Berton, Pierre. "Pierre Berton on the Klondike Gold Rush," The Canadian Encyclopedia, March 6, 2002. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/

Carter, Sarah. Imperial Plots: Women, Land, and the Spadework of British Colonialism on the Canadian Prairies. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2016.

City of Edmonton, "Population History," 2016. https://www.edmonton.ca/city_government/

The Edmonton Bulletin. March 28, 1891. Peel's Prairie Libraries, University of Alberta Libraries. Page 1. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/EDB/1891/03/21/1/

The Edmonton Bulletin. October 7, 1897. Peel's Prairie Libraries, University of Alberta Libraries. Page 1. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/EDB/1897/10/07/1/

The Edmonton Bulletin, December 23, 1908. Peel's Prairie Libraries, University of Alberta Libraries. Page 2. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/EDB/1908/12/23/2/

The Edmonton Bulletin, February 1, 1912 (Morning Edition). Peel's Prairie Libraries, University of Alberta Libraries. Page 2. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/EDB/1912/02/01/2/

The Edmonton Capital, September 22, 1914 (Special Mail Edition), Peel's Prairie Libraries, University of Alberta Libraries. Page 4. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/EDC/1914/09/22/4/

Edmonton Maps Heritage, "Urban Settlement." http://www.edmontonmapsheritage.ca/era/urban-settlement/

Gagnon, Erica. "Settling the West: Immigration to the Prairies from 1867 to 1914," Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21. https://pier21.ca/

Grant, John Webster. "Religion and the Quest for National Identity: The Background in Canadian History." Religion and Culture in Canada, Canadian Corporation for Studies in Religion, 1977.

Hesketh, Bob and Swyripa, D. Edmonton: The Life of a City. Edmonton: NeWest, 1995.

Von Heyking, Amy. "Schooling for "Good Character, 1905-1920," in Creating Citizens: History and Identity in Alberta's Schools, 1905-1980. (7-29) Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2006.

Hughes, Kathleen. Father Lacombe: The Black-Robe Voyageur. William Briggs Publishing, 1911.

Kent, Gordon. "100 Years of Amalgamation; Originally a Separate Community, Bustling Strathcona Was Absorbed by City on Feb. 1, 1912," Edmonton Journal, January 30, 2012.

Knowles, Valerie. Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy: 1540-1990. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1997.

Laurier, Wilfrid. "Wilfrid Laurier: Let Them Become Canadians, 1905," Canadian Encyclopedia, July 13 2017. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/wilfrid-laurier-let-them-become-canadians-1905

Leonard, D. "Knox (Presbyterian) Church." Alberta Register of Historic Places, Nov. 2005. hermis.alberta.ca/.

Leonard, D. "Strathcona Fire Hall No. 1," Alberta Register of Historic Places. February 2006. https://hermis.alberta.ca/

Macleod, Rod. "University of Alberta," The Canadian Encyclopedia. 14 Feb. 2013, www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/.

McCracken, Jane. "Homesteading," The Canadian Encyclopedia, February 10, 2009. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/

Michael, Gates. "Klondike Gold Rush". The Canadian Encyclopedia, July 19, 2009. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/klondike-gold-rush

Monto, Tom. Old Strathcona: Edmonton's Southside Roots. Edmonton: Crang Publishing, 2011.

Osterhammel, Jurgen. The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century, Princeton University Press, 2014.

Parks Canada. "Loyal Orange Hall #1654 of Edmonton." HistoricPlaces.ca, May 2005. www.historicplaces.ca/

Point Ellice House Museum and Gardens. "Point Ellice Bridge Disaster," 2019. https://pointellicehouse.com/point-ellice-bridge-disaster/

Plummer, Kevin. "Historicist: Orangemen and The Glorious Twelfth of July." Torontoist, 15 August 2011. torontoist.com/2008/07/historicist_orangemen_and_the_glori/

Saturday News, January 12, 1907, Page 2. Peel's Prairie Libraries, University of Alberta Libraries. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SDN/1907/01/12/2/

Saturday News, November 30, 1907, Page 10. Peel's Prairie Libraries, University of Alberta Libraries. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SDN/1907/11/30/10/

Strathcona Chronicle, January 22, 1909, Page 5. Peel's Prairie Libraries, University of Alberta Libraries. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers/SCC/1909/01/22/5/

Sullivan, Brian E. "Streetcars" The Canadian Encyclopedia, 5 Feb. 2015. www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/

Tingley, K., Shute, A., and Herzog, L. Building a Legacy: Edmonton's Architectural History. Regina: Coteau Books, 2012.

Thompson, Connor J. "Bricks, Faith, Community: A History of Edmonton Christianity to 1929," Alberta History, Spring 2018.

Wilcox, Michael. "Orange Order in Canada." The Canadian Encyclopedia, 6 June 2007. www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/