Walking Tour

Matsqui Village

Abbotsford's Scandinavian Settlement

Alexa Dagan

Nestled in the heart of the Fraser Valley, almost halfway between Greater Vancouver and the Coquihalla Mountain range, lies the city of Abbotsford. Sprawled across the rich farmland of the lower mainland, each corner of this city tells a different story, but none are quite like the Village of Matsqui.

Part of the traditional territory of the Matsqui First Nation, the land under Matsqui village was not settled British immigrants who colonized vast swaths of the Lower Mainland, but by a collection of settlers from Scandinavia. While they, like the British, were drawn to the Canadian west by promises of free land and a fresh start, they were a national minority in a largely British colonial landscape.

Yet their rich culture, religion, and traditions have left a subtle, but undeniable mark. Much like the traffic that passes through Matsqui on the way to Mission, after the 1930s, much of the development that changed the face of the Fraser Valley passed Matsqui by. The village today has changed little from its early days as a pioneer town, and many of the buildings retain their rustic, turn of the century charm.

In this tour, we wander through the village of Matsqui, using its historic buildings and landscapes to discover the roots of this frontier village, which is equal parts Canadian west coast, American midwest, and Northern European.

This short tour begins on Riverside Street, in between Elizabeth and George. The first two stops explore the land's original inhabitants, the Stó:lō, and their ongoing struggle with colonial legacies. Then we continue north on Riverside to learn the various factors behind the Scandinavian immigrants' decision to settle in British Columbia. Next, we stop at Matsqui's beautiful, and eye-catching church, to learn a little about Lutheranism and other Scandinavian values and traditions.

From there, we turn right onto St. Olaf street, named after the patron saint of Norway, and walk in the footsteps of the settlers as the community took shape around them. Then, as we continue up St. Olaf, we learn about the role of women in the community, the rise of the town, the architecture that characterised this period in Matsqui, and uncover stories from the community's pioneer school. Finally, we turn right onto Wallace, where we find out how Scandinavians in Matsqui eventually became one with their new homeland.

This project is a partnership with Heritage Abbotsford and we owe them generous thanks for their support. This project was funded in party by the Heritage BC Legacy Fund.

1. The Stó:lō

This photo shows a train arriving in Matsqui after construction of the rail link between Mission and Sumas. The train was symbolic of the incorporation of this land into the settler-colonial state--a sign of progress for some, but an ominous development for the Stó:lō Nation who had lived in this region for thousands of years.

Before the arrival of the trains, and the Europeans who built it, the vast sprawling floodplain before you was the land of the Stó:lō. The Stó:lō lived off the incredible bounty of the Fraser River and used the river and its network of tributaries as highways across their traditional territory that spread from the Fraser Canyon just past Yale in the east all the way to the river's mouth in the west. One of the bands that made up the Stó:lō Nation were the Matsqui, who lived in this area.

* * *

The first Indigenous peoples arrived in this area an estimated 9,000 years ago. Archaeological evidence indicates they were nomadic hunter gatherers, but they didn't stay that way for long. The astonishing richness and abundance of the lands allowed them to settle and adopt more sedentary lifestyles. By 3,000 BCE, these people, ancestors of the Stó:lō Nation, are thought to have numbered in the tens of thousands, and had developed a rich and complex culture and society.2

The Stó:lō Nation, or People of the River, are part of the Coast Salish peoples, and share many linguistic and cultural characteristics with the many other nations living around the Salish Sea. The Stó:lō speak Halq'emeylem, a dialect of the Coast Salish language Halkomelem.

The Stó:lō themselves consist of 11 different bands, of which the Matsqui First Nation are one. The Matsqui now live on reserve lands west of Matsqui Village, though their traditional territory was once much larger, including the village we'll be exploring in this tour. Matsqui means "stretch of higher ground."

What was Stó:lō society like before the arrival of Europeans?

Stó:lō society was both family and class-based, with the the Siy:ams--generally family leaders--at the top. Slaves, usually acquired during wars or raiding, were at the bottom. Slavery in Stó:lō society was not the brutal, chattel slavery practiced by Europeans in the Americas. By most accounts the slaves were treated well and mainly worked gathering and preparing food, or working as carpenters.2

Like other Coast Salish groups, the Stó:lō economy was based on the potlatch, or t'leaxet, a ceremony of complex gift exchanges which conferred status and rank, and redistributed wealth in a community. These ceremonies also allowed negotiations between and within villages and bands on status, titles, and territory.

Cedar played a critical role in Stó:lō society, as this versatile resource could be used for construction, clothing, medicine, canoes, rope, baskets, and art. Salmon also featured heavily in Stó:lō art and tradition. While hunted and foraged resources, such as wild berries, roots and, fish supplemented their diet, none were as important as salmon. The Stó:lō believed that salmon were the descendants of a Stó:lō ancestor who was turned into a fish by the Great Creator, and as such, salmon were highly regarded during ceremonies. The stupendous salmon runs on the Fraser Valley drew Coast Salish people from all around throughout the year, and ensured the Stó:lō abundant food supplies.

The Stó:lō lived this way for thousands of years, but their patterns of life would be calamitously upended by European contact.

The impact of the Europeans was felt even before any Europeans actually set foot on Stó:lō territory: smallpox, introduced by Europeans far to the east and south, spread through Indigenous peoples across North America, and reached the Lower Mainland sometime before 1782, when Simon Fraser reached the mouth of the river that would one day carry his name. The smallpox outbreak is estimated to have killed a shocking 2/3 of the Stó:lō, and caused the abandonment of village sites across the Lower Mainland.3

This was only the beginning. As more and more Europeans filtered into the region, the Stó:lō faced the destruction of not just their lifestyles, but the landscape to which they had been so intimately connected for time immemorial.

2. Dispossession of the Matsqui

1910

This view of Riverside Road is an early shot of the small Scandinavian community that grew up here.

Before we turn to them in detail, we must ask how Europeans came to occupy all this land, which is the ancestral territory of the Matsqui. The Matsqui, one of the bands making up the Stó:lō Nation, were initially given a large grant of land by the British authorities who ran the colony of British Columbia in the mid-1800s. However, after James Douglas stepped down as governor in 1864, a far more brutal and explicit policy of dispossession of Indigenous lands was immediately implemented by Joseph Trutch.

Within months the Matsqui found 99% of their lands sold out from underneath their feet without their consent or even consultation.1 They were confined to a tiny reserve on the banks of the Fraser River and subjected to a legal regime that relegated them to the status of second class citizens. The Matsqui continue to fight for redress over the theft of their lands to this day.

* * *

Before we turn to them in detail, we must ask how Europeans came to occupy all this land, which is the ancestral territory of the Matsqui. The Matsqui, one of the bands making up the Sto:Lo Nation, were initially given a large grant of land by the British authorities who ran the colony of British Columbia in the mid-1800s. However, after James Douglas stepped down as governor in 1864, a far more brutal and explicit policy of dispossession of Indigenous lands was immediately implemented by Joseph Trutch.

Within months the Matsqui found 99% of their lands sold out from underneath their feet without their consent or even consultation.1 They were confined to a tiny reserve on the banks of the Fraser River and subjected to a legal regime that relegated them to the status of second class citizens. The Matsqui continue to fight for redress over the theft of their lands to this day.

3. Leaving Scandinavia

1912

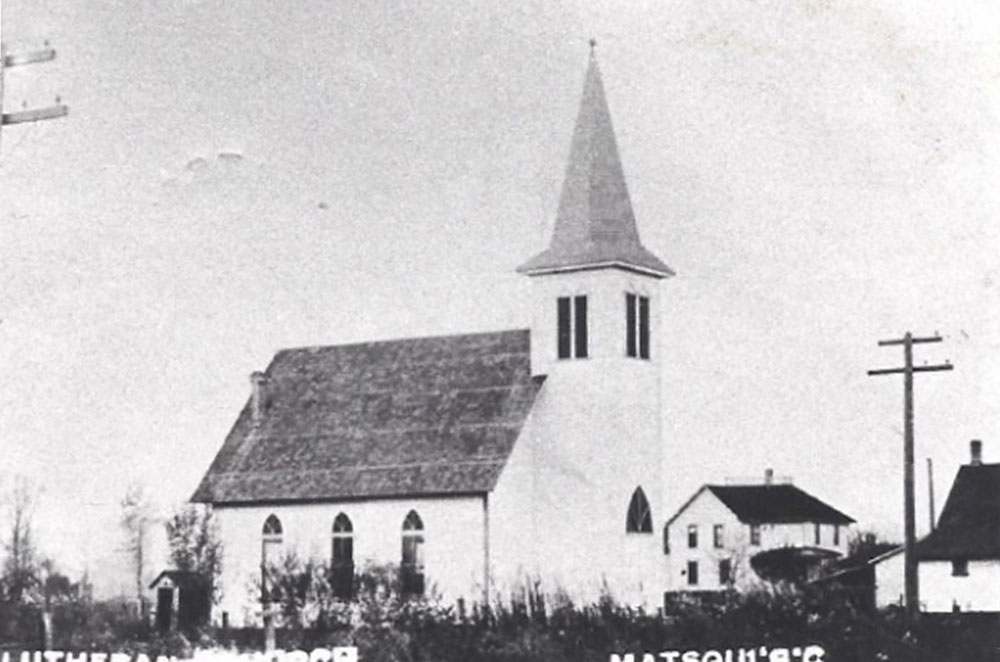

This is Matsqui's Lutheran Church, built in 1903. It's probably the oldest surviving church in Abbotsford, and one of the only physical traces you can still find of the origins of Matsqui's village. The simple log structure is a design that dates back to the Middle Ages, and is "exactly like a Scandinavian visitor would expect."1

Around the time this church was built the majority of immigrants coming to British Columbia were British. Matsqui was different: This community was established by people from Scandinavia, primarily from Norway, and Sweden, as well as some from Finland. They were just a few of the hundreds of thousands of Scandinavian immigrants who had caught 'Canada fever,' a desire to escape their harsh lot at home and start over in the Canadian West.

What drove these people to get 'Canada fever' and make the risky journey to start a new life in a distant land?

* * *

It was an agrarian society, not yet an urbanized one, and even though over half the population survived through subsistence farming, the mountainous terrain meant there was little good farmland to go around. The vast majority of people lived under a "rigid and degrading class system that demanded outward submissiveness to the upper class and political and religious leaders," writes one scholar of Swedish history.2

As a Norwegian immigration officer in Quebec City wrote in 1865, "If an emigrant is asked why he leaves the country, the answer is always that he finds great difficulty in obtaining a livelihood at home, and that in North America they are not so much exposed to failure of crops.. The complaints are most frequent of want of work and small wages particularly during the winter, and these complaints are no doubt made with good reason, as there are parts of Norway where an ordinary labourer, during the winter, cannot earn more than 3 to 4 pence a day beside his board."3

The authoritarian government had a limited democracy, but most men and all women were denied the vote. The press was censored. Like most European states at the time, conscription (mandatory military training for all males) was enforced, and then expanded to four months a year every year for four years. By comparison, soldiers in Canada's Army Reserve today are expected to serve two weeks a year--and obviously it's voluntary.

It's hardly surprising that many Scandinavians were unhappy with their lot in life and wanted to leave. In fact the widespread poverty and lack of good land were the same factors that encouraged thousands of Scandinavians to sail from their shores and take to raiding, adventure, and conquest during the Viking Age between 800 and 1100 CE.

Viking traditions of seamanship had persisted in Scandinavia over the eight intervening centuries: Norway in 1905, out of all proportion of its a tiny population of two million, boasted the world's fourth largest merchant fleet, behind only Britain, the USA, and Germany.4 5 And so thousands of impoverished young Norsemen again took to the sea in the 1800s, not to pillage and raid, but to man the ships plying global trade routes. In the process they saw the world, and with it the opportunities that existed beyond their borders.

When these sailors brought back tales of freedom and free land in America, excitement swept across the kingdoms. In a few short years 'America Fever' had swept over Scandinavia. Entire valleys emptied out and villages abandoned. By the 1880s hundreds of thousands of Swedes, Norwegians, and Finns had made the journey to America. A few of them had come to Canada, too, but it wouldn't be until the 1890s that a new wave of fever, this time for Canada, would sweep Scandinavia.

4. Canada Fever'

1925

This was the home of J.P. Kemprud in 1925. The Kempruds were one of the founding Scandinavian families around which the Village of Matsqui was built. J.P. Kemprud was a prominent local businessman, and his wife Anna started the village's first restaurant here, making her one of the first female business owners in the area.

We have seen why so many Scandinavians were eager to emigrate from their homeland, but what made them choose Canada? There were three main factors: In the 1890s the US West was largely settled and they'd run out of free land to distribute. Shortly thereafter the Canadian government sponsored aggressive initiatives to get Swedes and Norwegians to come to Canada, and finally coastal British Columbia, with its rugged mountains and temperate climate, very much resembled their homeland.

* * *

The Canadian Government on the other hand, had only just opened up its western provinces to settlement after the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed in 1886. The government was eager to fill these areas with European farmers who would assume the newly-forming Canadian identity.

The Dominion Lands Survey gave male claimants 65 hectares of land for a small $10 administration fee, and it was theirs so long as they built a permanent dwelling on it and farmed part of it within 3 years.

These campaigns reached their height during the government of Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, who directed his energetic Minister of the Interior Clifford Sifton to launch the famous and highly successful "Last Best West."

For Sifton, the ideal candidates were those from America, or the British Isles, followed in order by Northern and Western Europe, then Eastand Southern Europe, with visible racial minorities seen as the hardest to assimilate into Canadian culture, and therefore least attractive (racist attitudes played no small part in these calculations).

The account of Matthew S. Anderson, a Norwegian farmer homesteading in Minnesota, shows just how organized these government campaigns were:

"I seemed not to be progressing the way I had hoped for in the New World. Consequently, when I called for my mail at the Crookston (Minnesota) post office one Sunday, I examined with new interest some large posters on the wall describing how one could get free land in Canada.

"The posters carried beautiful pictures of what they called "A Northwest Paradise". One showed a lovely lake with fish jumping out of the water.

"As I was looking at the posters, a man approached me and asked if I would be interested in taking up a Canadian homestead. When I replied in my somewhat broken English he began to speak in Norwegian. He was a Norwegian and was employed as a sub-agent for a land company in Canada...

"When we told our acquaintances that we were considering moving to Canada, they told us it would be a very risky move. It was a very lawless country, they said. We were to find out that they did not know what they were talking about."1 According to one scholar, "In thousands of cases, the 'American fever' had now subsided and many now caught the 'Canada fever' while down in the United States."2 These arrivals sent word of the new 'Northwest Paradise' back to their friends and family in Scandinavia, and infected thousands of them with the fever too. The first wave of Scandinavian immigration to Canada had begun.

5. Lutheranism & Nordic Culture

1905

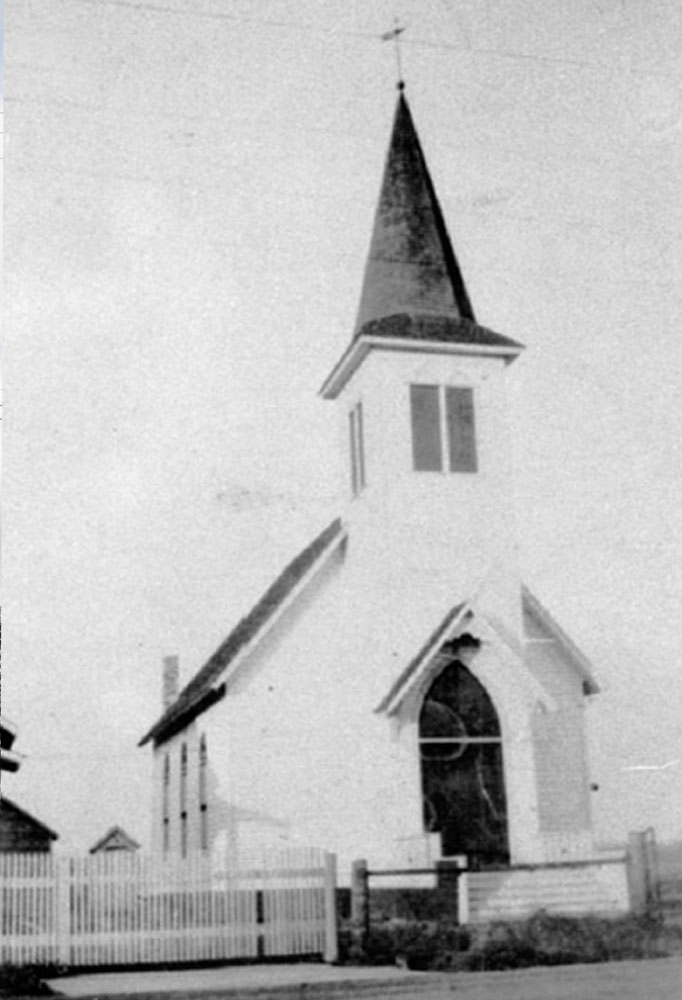

This is another view of the Lutheran Church, which was originally named Goshen Evangelical Lutheran Church. This church replaced an earlier one as the primary place of worship in Matsqui, and was built on land donated by a local man for that express purpose.

While this building has obvious Scandinavian roots, it defies many Scandinavian Lutheran architectural conventions. Most Lutheran churches were built in an east-west orientation, with the chancel on the eastern side, and the entrance facing west. But this church is the opposite. For the new settlers, location was more important than orientation, for the church had to be the focal point of the community. If they had followed convention, the bell tower and entrance would have been set away from the intersection, facing away from the nexus of the village.

The vast majority of immigrants to BC coming from Europe in this period were British, meaning they were almost all Christian, but Baptist, Anglican, Methodist, or Presbyterian. There were also many Irish Catholics. Lutheranism was distinct to Northern Europe, so you won't see many Lutheran churches outside of communities without strong Scandinavian or German roots.

What kind of religious beliefs and cultural traditions did the Scandinavians immigrants have?

* * *

As Abbotsford historian Christina Reid puts it, "The church is also 'typically Scandinavian' in the psychological sense: it is, notably, not Henry III's Westminster Abby, built on big dreams, but instead, designed to fit it the new landscape, i.e. not to stick out. Much like the Scandinavian pioneers themselves, it disappears into the crowd and becomes one of many."1

Most of the Lower Mainland's settlers were overwhelmingly English and Scottish, and therefore Anglican, Methodist or Presbyterian. The Scandinavians were overwhelmingly Lutheran. While all are Christian, there are significant differences between them in their practices, interpretations of scripture, and beliefs.

The Anglicans and the Lutherans broke away from the Catholic Church at around the same time, but for entirely different reasons. In 1517 the German priest Martin Luther nailed his famous 95 Theses to the door of Wittenberg Cathedral outlining his complaints with the Catholic Church, and igniting the Protestant Reformation.

Luther believed that Christians could not attain salvation through good deeds alone but that salvation was attained through individual faith in Jesus Christ as sole redeemer of sin. These teachings also emphasized that only the bible can teach divine knowledge, and that any Baptised christian could directly connect with the word of god without the mediation of the priesthood.

Anglicanism, on the other hand, was largely the result of King Henry VIII's infamous struggle with the Pope to divorce his wife, an argument that concluded with Henry cutting ties with Catholicism.

The Lutheran Swedes and Norwegians who settled in Matsqui brought some of their own particular cultural practices. Especially notable is how they celebrated Christmas, a major festival that involved the entire community.

In the Norwegian tradition, animals were slaughtered a month in advance so the meat could be spiced and prepared, and special cheeses and dishes were made. There was: "endless baking of a large assortment of traditional cakes and breads including flatbrod, a crisp, very thin unleavened bread. Mothers were exceptionally busy far ahead making clothing, for custom dictated that every member of the family should have at least one new thing to wear for the first time on Christmas Eve."2

On Christmas Eve, families celebrated with a special early evening meal, "Usually rice or cream pussing (rommergrot) was included as an extra special item. Always there would be lefse, eaten buttered and rolled. After the meal, the candles were lit on the tree. The youngest members of the family were selected to distribute gifts often lovingly and secretly crafted for one another. "3

6. Destination British Columbia

This photo features what was once Matsqui's second Post Office. Matsqui's first post office was built in 1902, and was originally both a post office, and a store. The original building still stands at 33677 St. Olaf, but the post office was moved to the building you see here in the mid 20th century. It has since moved again to a new building on Riverside Street.

The post office not only facilitated communication between Matsqui and the rest of Canada, but allowed Scandinavian settlers to keep in touch with relatives scattered across North America, and those still living back home.

* * *

Following his establishment of the fishery, other Scandinavians followed. The first large colony settled in Bella Coola in 1894 when 85 Norwegian settlers from the American Midwest made their way to the west coast. Similarly, Quatsino, a small hamlet on northern Vancouver Island, was settled by Norwegian farmers from North Dakota who arrived via steamship in 1894 to homestead and farm thirty 80-acre lots. Outside of Matsqui, these two were the only other Scandinavian settlements of any size in BC.

The arrival of the Scandinavians at Bella Coola was welcomed by the Victoria Daily Colonist, which wrote favourably of their determination and work ethic: "Scandinavians make good settlers. They are intelligent, sober, pious, industrious and self-reliant. They do not expect too much. They come from a country where nature is not very generous - where men have to work hard and continuously to gain a comfortable livelihood, and they therefore will not be discouraged when they are required to face the difficulties and endure the hardships and privations of pioneer life."1

It's no surprise then that Alex Cruikshank, appointed manager of the Matsqui Land Company in 1898, explicitly sought out Scandinavian settlers for the community he hoped to develop here.

7. A Community Takes Shape

1925

This distinctive building is in a very poor state of repair today, but it was once at the centre of the community's commercial area, and housed a garage, Lightbody's Pharmacy, and later the town's library. It was built in 1925, shortly before this photo was taken.

In 1898 Alex Cruikshank, owner of a nearby farm, was appointed manager of the Matsqui Land Company. His task was to build up a settlement here. Today this might look like an easy place to settle, but in those days the Fraser River had yet to be dyked, and frequent flooding threatened anyone who settled here. He wanted hardy pioneers who would stick it out, and help build the desperately needed dykes. He sought to lure Scandinavians from the American Midwest with promises of land and good paying work.

The first family, the Hougens, arrived in 1899 and began farming the 160 acres promised by the Dominion Lands Act. They liked it well enough that soon more of their countrymen were coming from America and also directly from Scandinavia. Within a few short years 18 Scandinavian families had settled in Matsqui.1

* * *

It wasn't until 1888 that local landowners formed the Matsqui Land Company to try again. Throughout the 1890s they tried repeatedly to hold the waters back and reclaim the land--and failed every time.

Finally in 1898 the provincial government took an interest, and saw that the dykes were completed. It was hoped this time they'd hold.

With the Matsqui Prairie reclaimed, it was time to find settlers, and the Matsqui Land Company's Cruikshank began advertising in the American Midwest. The first to arrive were generally individual men, who came alone hoping to put down roots. "It was not until the village had stabilized that these immigrants encouraged spouses and other family members to come."2 The first families to arrive, the Kempruds, the Hougens, and the Swards, anchored the community and gave it a heavily Scandinavian influence. Soon many more were to follow. A 2015 study by Christina Reid found of the 53 families residing in Matsqui, 23% were Scandinavians who immigrated from the US, and another 47% came directly from Scandinavia.3

8. Getting to Work

1923

Two men pose with a team of harnessed horses in front of the Patterson blacksmith shop, which was built around 1915. During this time there were blacksmiths all over Abbotsford, though this is the last surviving one where the building still stands.

Blacksmiths were some of the most important tradesmen in the pioneer towns. Their work included shoeing horses, repairing wagon wheels, and repairing farm machinery. In the early 19th century, separate craftsmen handled various metalworking tasks in small communities, but by 1850 all of these amalgamated under the blacksmith's banner. They were especially important in farming communities like Matsqui.

* * *

The first few years of establishing a homestead required intense physical labour. First, the land had to be cleared of any trees, stumps, and shrubs. In a time before chainsaws, this was time-consuming and often dangerous work undertaken with axe and saw. Then followed the work of building a home and making the land suitable for agriculture. Once this was completed however, they were well rewarded: the rich soil of the Fraser Valley supported a wide variety of crops and livestock. Today, the most common crops in Abbotsford are hay and fodder, nuts and berries, and of course, vast fields of corn.

A number of men took up jobs in construction, including the Olund brothers and the Flodin who ended up building most of the homes and businesses in the community--even while having their own farms to maintain.

As farms sprang up all around Matsqui Prairie, the village itself became a little commercial hub, and a number of businesses, like this blacksmith, and the garage in the previous stop, were established by the Scandianavian settlers.

9. Women in Matsqui

1931

This photo shows a lone woman standing on the porch of this home on Olaf Street. In addition to being the home of several of the village's pioneer families it is also one of Matsqui's earliest uses of stucco siding.

For Norwegian women, gender roles were similar to those in England or America. Women generally took charge of the home and children, while the men were the 'providers.' However, in this role, Norwegian women were seen as being more independent and assertive than Canadian women from other backgrounds.

This was remarked upon by other settlers: author Gulbrand Loken writes "It seems no wonder that one Englishman blurted out, 'What unbelievable women these Norwegians have!'" He continues by saying that while the father was head of the family, the mother was "the neck that turned the head."1

* * *

One of the major reasons for the enterprising nature of women in BC was the legacy of the gold rushes where women were able to capitalize on skills they developed in their traditional gender sphere, "providing a range of services for a largely male population." Brothels too, offered a lucrative opportunity for self-employment, although that particular brand of employment was accompanied by significant public stigma.

Even after the gold rushes and the establishment of stable settlements in BC, the enterprising spirit of women persisted. However, women in the workforce in any occupation were not free from scrutiny. There was some stigma for self-employed women especially. In the early 20th century, many believed that there were certain qualities that were necessary for one to succeed in business, and that these qualities, such as aggression, competition, and ambition, were inherently masculine. And so, women in business were forced to walk a thin line, trying to project those seemingly masculine qualities, while trying to maintain their femininity. Female business owners who were conventionally feminine in every other regard, were much less threatening to those who upheld the status quo.

10. The Peak

1935

This is the Matsqui Hotel. It was built in 1914 to replace an earlier hotel on the same spot. Despite the owners' Scandinavian roots, the hotel is built in a North American style: you wouldn't find many buildings with flat roofs in Sweden, they risked collapsing under the weight of snow!

Matsqui itself ceased growing during the Great Depression, when this photo was taken, as any new arrivals opted to settle in the nearby Mennonite community of Clearbrook instead, which was thriving. In addition, a new bridge to Mission meant farmers on the Matsqui Prairie could go there to get their shopping done, bypassing the village altogether. As Heritage Abbotsford's Christina Reid explains, from this point "instead of becoming a ghost town... Matsqui neither grew nor shrunk, but seemed to become frozen in time."1

* * *

Many of these migrants came seeking scarce work in the logging camps and fishing fleets around the Lower Mainland, while some others would work in the farms around Matsqui. Workers like them would frequently stay in the Matsqui Hotel here during harvest season. The hotel offered a diverse array of other services, including a public baths and pool hall, and housed a dressmaking shop.

Hotels for young men to live in while working nearby were a common feature of life in BC around this time, and some, like Vancouver's Swedish Boarding Houses at Cordova and Carrall were founded specifically to help Scandinavians. Vancouver's first famous hotel man, Pete Larsen, was a Swede. He established the storied Hotel Norden in 1887, and the Union Hotel for sailors shortly thereafter.2

Back in Matsqui, from the 1920s the growing popularity of cars meant temporary farm workers could commute long distances to and from work, and this hotel declined in importance. Today the hotel has been closed, but it has been well preserved to the present.

11. A Common Building Style

1920

This house, built in 1900, is one of the early examples of typical architecture in Matsqui. Although the building has been remodelled several times over the years, it's largely unchanged since its last serious renovation in 1926 by local contractors, O. Olund, Kemprud and Hanson. Like many of the buildings in Matsqui, this house is two storeys, and built with clapboard siding. Despite the community's Scandinavian roots, most of the buildings are constructed in a style that is clearly North American.

Scandinavia had long and well-established building traditions, but as we can see from this home, and many of the buildings in this community, Scandinavian architectural influences can be hard to find. Local builders brought with them American styles they'd adopted in their time in the American Midwest, and made use of local materials to adapt to local conditions.

* * *

However, eventually the log house too fell out of fashion, and by the 1890s board and batten siding became common. Board and batten siding uses wide vertical planks (boards) which are joined by thin vertical strips (battens) that cover up the seams for weatherproofing. Up to the early 19th century, it was common to stain the wood a deep red, with bright white gables. The red stain rose in popularity because it was economical and had the added benefit of preserving the wood. The stain was later eclipsed by lighter colours, such as yellow and white.

In Matsqui however, the board and batten siding was replaced by a style more typical to pioneer communities in western North America. Here, clapboard siding reigns supreme. Clapboarding is constructed using long, narrow horizontal planks, which were thicker on the bottom edge to overlap the thinner edge of the board below it. This style not only takes advantage of the region's seemingly unlimited forests, but also provides cheap, easy weatherproofing against the west coast's rainy climate. The roads and sidewalks too, were built with the rain in mind, with the roads crested in the middle to encourage run-off, and wooden sidewalks raised above the sucking quagmire below.

One of the factors that makes Matsqui so quaint is the cohesive style of the community. Most houses are constructed in similar architectural styles and designs, giving the village a tight-knit, unified feel that builds on the town's collective national heritage, even if the building styles don't perfectly reflect those popular in the mother country.1

12. Education in Matsqui

1942

This is Matsqui's Community Hall. Built between 1907 and 1915. It was used early on as a community school. The hall was also the central gathering place for the Norwegians, Swedes, and Finns who called this place home, and it has seen thousands of joyous events over the years. Today it continues to host meetings, dances, and wedding receptions.

It's role as a school early on was important, as the settlers here placed enormous importance on educating the next generation. "In general, the Norwegians in Canada were faithful patrons of public school education from kindergarten to university," writes the historian Loken Gulbrand.1

* * *

The Lutheran Church stepped in to fill the gap, offering schooling outside the public system. They worked to pass on faith and religious education to the next generation, and also ensuring children received some knowledge of their community's cultural heritage and their mother tongue (Swedish or Norwegian).

According to Gulbrand, "The schools that were established in Canada were a combination of the heritage from Norway and the organizational example of the United States."2 Church education began at home, and continued until adolescence, where the ages of 14 - 16 consisted of intense memorization and review of texts. Once this education was over, the church accepted teens as full adults and church members.3

Matsqui Elementary offered public schooling. That school has stood in the same spot a block south of here for over 100 years. The school, however, looked much different in the early 19th century than it does today.

Recently, local World War II veteran Mr. Ernie Poignant, spoke to the students at Matsqui Elementary about his experience attending the school as a small child from 1926 -1934.

Poignant walked a little over three kilometers every day in order to attend the class he shared with 33 other students, between grades one to five. The age of the students was apparent in their uniforms, boys in the younger grades wore short pants while older students wore long trousers. The most noticeable difference we might see today, is that during this period, the school had no indoor plumbing, and students had to go outside in any weather to use the outhouse. Poignant also recalled that his father brought fresh water to the school often as there was no running water.4

Following his education, Poignant served in the Canadian army from 1944 to 1946, with postings in Vancouver, Nanaimo, Victoria, and Camp Borden in Ontario. After the war, he became a journalist and worked for the Maple Ridge Gazette as a compositor and cartoonist. Poignant celebrated his 100th birthday in 2019, and is a deeply respected member of the Abbotsford community.

13. The Invisible Immigrants

1939

This photo was taken during the royal visit by King George V to Matsqui just before the outbreak of the Second World War, when he stopped at the station located approximately on this spot. Though nominally independent and self-governing, Canada still had very close ties to Britain. British culture and traditions dominated, especially in western Canada, and immediately upon their arrival the Scandinavians were under considerable pressure to assimilate into this Anglo-Canadian society.

The cultural assimilation of the Scandinavians was so complete, that a recent study on Swedish Canadians was subtitled 'The Invisible Immigrants.' What cultural pressures were Scandinavian Canadians under, and how did they respond?

* * *

There was a strong expectation that these immigrants learn English as soon as possible, and adopted Anglo-Canadian dress and behaviour. Advancement in society usually entailed successfully blending in. Without a doubt, the Norwegians, Swedes, and Finns who arrived in Canada wished to preserve their language and culture, but, under these conditions, this was no easy task. Scandinavians never won the right to have their language taught in public schools.

Racism was widespread at the time, and many groups of immigrants, such as the Chinese, Indians, and Africans, would struggle for decades to overcome discrimination. The Scandinavians on the other hand had the advantage of being white, and being culturally similar to the British, so they were "readily accepted into Canadian society with its British antecedents."3

This acceptance wasn't always smooth. During the First World War Sweden was widely seen as being too friendly to Germany, and Swedish people were discriminated against, Swedish language press in Canada censored, and there was even a small anti-Swedish riot in Winnipeg in January 1919.

Nevertheless, Scandinavians rapidly adopted their new Anglo-Canadian identity. This was helped by their willingness to learn English, and ease in doing so since the languages are quite similar. Public schooling, and high levels of educational attainment amongst Scandinavian Canadians also helped. As the geographer William Wonders wrote, "From the viewpoint of culture there is, strictly speaking, very seldom any second Scandinavian generation."4

Some regretted the feeling that their culture was slipping away. As Laura Derdall, a Norwegian Canadian, wrote: "I didn't have much trouble learning to speak English, or adapting to this country. My husband had more difficulty. He learned his English working in a sawmill in the States. It seems that the Norwegian traditions have been difficult to carry on. I have kept up my Norwegian baking. I feel it is too bad that the young people show no interest in learning to speak Norwegian or in carrying on the traditions."5

Nevertheless, their Nordic past was not entirely forgotten. As Gulbrand Loken writes:

"Most of them still open their presents on Christmas eve rather than on Christmas morning. There well may be lutefisk and lefse on Christmas Eve, but likely Canadian turkey on Christmas day. On the whole, Norwegians do not feel that they belong to a less-favoured group any longer, nor is there a sense of isolation or discrimination. Their Nordic traits are shared and respected."6

14. Keeping Tradition Alive

1912

This photo of St. Olaf Street, is one of the earliest shots we have of Matsqui Village. Foremost in this shot is Halverson and Hougan's Store, which provides not only general merchandise, and farm tools, but also insurance and real estate. The store also doubles as the community's post office. With it's muddy crested road, and raised wooden sidewalks, this snapshot closely resembles many other photos of BC's frontier towns in this period.

* * *

The Sons of Norway, the largest Norwegian organization outside of Norway, is a community based organization dedicated not only to providing community to those abroad with Norwegian ancestry, but to preserving their culture, language, and traditions. In BC, there are 15 Sons of Norway Lodges across the province, several of which are in nearby Chilliwack, Surrey, Langley, and Maple Ridge. Conspicuously, Matsqui, one of only three Scandinavian settlements in BC, and Abbotsford, are lacking Sons of Norway houses.

While Matsqui may not be the home of a Swedish or Norwegian fraternal organization, the community still keeps aspects of their heritage alive every day through small traditions. Local historians too, are hard at work preserving Matsqui's history and heritage buildings, and at keeping the village's cultural memory alive. In this town, one only need look towards the iconic white church to see how cultures can come together and blend beautifully in the heart of Canada's west coast.

Endnotes

1. The Stó:lō

1. Christina Reid, "A History of Abbotsford," Tretheway House Heritage Site, online.

2. Reid, "A History of Abbotsford," online.

3. Sandra Shields, "'We weren't supposed to survive'" The Tyee, March 7, 2007, online.

2. Dispossession of the Matsqui

1. John Lutz, "Joseph Trutch, B.C's first lieutenant-governor, left a trail of controversy," The Times Colonist, June 17, 2018, online.

2. Christina Reid, "Building on Tradition: A Study of Matsqui Village." University of Leicester, School of Archaeology and Ancient History, M.A. Dissertation, (June 2015), 5.

3. Reid, "A History of Abbotsford," online.

4. Lutz, online.

5. Patrick Penner, "BC First Nation makes claim for sale of reserve lands 150 years ago," The Free Press, Oct. 9, 2019, online.

6. British Columbia Terms of Union, Clause 13, May 16, 1871, online

3. Leaving Scandinavia

1. Gulbrand Loken, From Fjord to Frontier: A History of the Norwegians in Canada (Toronto: Minister of Supply and Services Canada, 1980), 33.

2. Elinor, Barr, Swedes in Canada: Invisible Immigrants, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015), 267.

3. Loken, 33.

4. Stig Tenold, Norwegian Shipping in the 20th Century, (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 15.

4. Canada Fever'

1. Loken, 44.

2. Loken, 44.

5. Lutheranism & Nordic Culture

1. Reid, Building on Tradition, 38.

2. Loken, 218.

3. Loken, 218.

6. Destination British Columbia

1. Loken, 78.

7. A Community Takes Shape

1. Reid, Building on Tradition, 24.

2. Reid, Building on Tradition, 26.

3. Reid, Building on Tradition, 25

9. Women in Matsqui

1. Loken, 217.

2. Melanie Buddle, "'You have to think like a man, and act like a lady,': Businesswomen in British Columbia, 1920 - 80" BC Studies, No. 151, (Autumn 2008): 69.

10. The Peak

1. Reid, Building on Tradition, 6.

2. Barr, 83.

11. A Common Building Style

1. Reid, Building on Tradition, 32.

12. Education in Matsqui

1. Loken, 130

2. Loken, 131.

3. Loken, 131.

4. Terry Jung, "Guest Blog: Bringing History to Life," Matsqui Elementary, Feb 2, 2015, online.

13. The Invisible Immigrants

1. Loken, 189.

2. Loken, 187.

3. Barr, 5.

4. Loken, 193.

5. Loken, 188.

14. Keeping Tradition Alive

1. Reid, Building on Tradition, 25.

Bibliography

Barr, Elinor. Swedes in Canada: Invisible Immigrants. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015.

Buddle, Melanie. "'You have to think like a man, and act like a lady,': Businesswomen in British Columbia, 1920 - 80" BC Studies, No. 151, Autumn 2008.

British Columbia Terms of Union, Clause 13, May 16, 1871. https://www.solon.org/Constitutions/Canada/English/bctu.html

Jung, Terry, "Guest Blog: Bringing History to Life," Matsqui Elementary, Feb 2, 2015. https://matsqui.abbyschools.ca/blog/guest-blog-bringing-history-life

Loken, Gulbrand. From Fjord to Frontier: A History of the Norwegians in Canada. Toronto: Minister of Supply and Services Canada, 1980.

Lutz, John, "Joseph Trutch, B.C's first lieutenant-governor, left a trail of controversy," The Times Colonist, June 17, 2018.

Penner, Patrick. "BC First Nation makes claim for sale of reserve lands 150 years ago." The Free Press, Oct. 9, 2019. https://www.thefreepress.ca/news/matsqui-first-nation-files-claim-against-federal-government-for-sale-of-reserve-lands-150-years-ago/

Reid, Christina. "A History of Abbotsford," Tretheway House Heritage Site,

Reid, Christina. "Building on Tradition: A Study of Matsqui Village." University of Leicester, School of Archaeology and Ancient History, M.A. Dissertation. June 2015.

Sheilds, Sandra. "'We weren't supposed to survive'" The Tyee, March 7, 2007. https://thetyee.ca/News/2007/03/30/Stolo/

Tenold, Stig. Norwegian Shipping in the 20th Century. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.